This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 753 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser and what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, funding comments section support.

By Caroline Metz, a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute, and a member of the Critical Political Economy Research Network. Originally published at openDemocracy

Image: Jay Tamboli, CC by 2.0

The financialisation of non-performing loans across Europe raises grave concerns over debtors’ rights.

European households’ and businesses’ struggles to pay their debts constitute a business opportunity for debt collectors and global asset managers looking to make good returns on investment. Yet the ongoing creation of a European market for distressed debts, and its active promotion by European institutions, raise important questions, both ethical and political, about whether we should rely on financial markets to tackle social issues such as indebtedness.

The austerity programmes imposed by the International Monetary Fund, the European Central Bank and the European Commission and implemented by governments after the 2008 financial crisis have affected living standards throughout Europe, particularly in so-called peripheral European countries. Governments have slashed funding in healthcare, pension, education, transport and culture; welfare benefits have been cut and VAT taxes hiked; and growing numbers of public services have been privatised, all with devastating effects on public health. At the same time, unemployment and precarious contracts have become risen dramatically, and wages have decreased in real terms.

Insufficient revenues and inadequate state support, combined with credit that’s all too easy to access, have pushed many households to rely on debt to meet basic needs or pay for unexpected expenses such as illnesses. Yet as economic conditions have largely failed to improve – worsening still in some countries – people have also increasingly struggled to make regular debt payments. Most European countries have seen a rise in levels of arrears and over-indebtedness, and a surge in debt defaults since the global financial crisis.

In financial jargon, defaulting loans are known as ‘non-performing loans’ (NPLs). From the perspective of creditors (banks for example), a loan is indeed said to be ‘performing’ when it keeps bringing fresh and profitable cashflows in the form of regular payment of principal and interest. When these payments become irregular, late or non-existent, the loans become ‘non-performing’ and no longer profitable. In what follows, the terms bad debts, distressed debts, defaulting debts and NPLs refer to situations where debtors are having difficulties making payments, are defaulting, or at high risk of default due to late and irregular payments.

The Rise of Debt Defaults in Europe

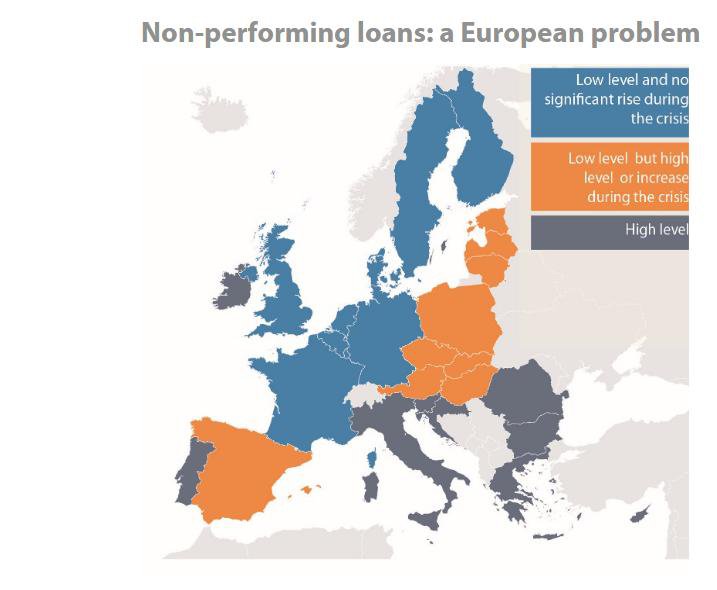

The share of non-performing loans rose across the EU after the financial crisis, reaching a peak of 7% in 2012-2013. Current levels of NPLs in the Euro Area (6.2%) are six times higher than in the United States (US) and Japan, each with about 1% of NPLs, and European banks still hold €786 billion NPLs, with consumer loans (including mortgages) making up a third of this amount.

Zooming in on non-performing household loans, although the EU average was 4.3% in 2016, the situation was much more worrying in Italy and Ireland (above 15%), and even more so in Greece and Cyprus, where one in two households is not able to repay its debts.

Debt Defaults: Threat to Financial Stability, or Business Opportunity?

Although there has not been much mainstream media attention to the topic of distressed debt, the situation is alarming. The rise of NPLs signifies that individuals are living in precarious conditions which do not allow them to continue making ‘normal’ debt payments. This, in and of itself, should worry us.

European institutions, however, see another issue with NPLs. The European Central Bank, which is now also responsible for the stability of large European banks, sees NPLs as a problem for banks, and for the financial sector as a whole. The ECB argues that NPLs ‘weigh on banks’ profitability’ and reduce their capacity to issue new loans. NPLs are seen to be a threat to the stable functioning of the European banking system, and as such they are ‘one of the top three priorities’ of the ECB.

Interestingly, not everyone considers bad debts to be a problem. The financial industry, in fact, very much sees them as a business opportunity. A 2018 report by Ernst & Young called on investors to seize the ‘opportunity out of adversity’ that Greek non-performing loans represent. US private equity fund KKR teamed up with four Greek banks to invest in ‘their big troubled borrowers’, while PIMCO and Fortress, two major US-based asset management firms, acquired €17.7 billion of NPLs from Italian bank UniCredit.

2018 was a record year for the sale of NPLs, with €205 billion worth of distressed European debts changing hands (by comparison, Greek GDP in 2018 was €185 billion), often to land on the other side of the Atlantic – the top 10 investors in European NPLs are from North America.

The sale of NPLs can be direct or indirect. In a traditional NPL sale, a bank sells a portfolio of distressed loans at a highly discounted price (40% to 50% for mortgages and up to 90% for other types of unsecured loans) to one or several investors such as hedge funds or private equity firms, which then try to recover as much value as possible on the loans.

The indirect sale of NPLs takes place via the use of a special purpose vehicle which issues securities backed by a pool of NPLs. You might recognise in this form of exchange – called securitisation – the technique at the heart of the US subprime mortgage crisis which triggered the global financial crisis. Securitisation, it turns out, played an important role in NPL sales in 2018 (it was used in half of the 64 bad debt deals in Italy that year) and is expected to continue doing so going forward.

Markets to the Rescue: The Financialisation of Debt Defaults

Such transactions are, according to the ECB, one of the key ways in which banks should aim to deal with NPLs. The ECB only laments that these markets are ‘often underdeveloped’. European institutions, in fact, have been active supporters of the development of distressed debt markets.

The European Commission, in a new Directive proposal aimed to develop NPL markets, proposes to facilitate the cross-border activity of debt collectors, so that investors in NPLs, who might be located outside Europe, can more easily make returns on their ‘investment’ in troubled debtors in one or several European countries.

Altogether, the sale and securitisation of defaulting debts, as well as regulatory changes aimed to ease these transactions, can be described as the ongoing marketisation of bad debts (turning them into commodities exchangeable on a market). More broadly, then, we are witnessing a financialisation of bad debts, whereby distressed debtors are unknowingly enrolled in financial market transactions which bring hefty profits to a variety of financial firms such as global investment funds, hedge funds, (North American) private equity funds and debt collection firms.

Practical Doubts and Ethical Questions

There are at least three reasons why we should be concerned with the marketisation and financialisation of bad debts in Europe. First, in practical terms, there is no need to go far back in history to see that current arguments around the necessity to create bad debt markets are littered with flaws. ECB claims that ‘banks can transfer the risk of holding NPLs to non-bank investors’ echo arguments made in the early days of securitisation.

We have found out the hard way that the rapid expansion of structured finance increased rather than dispersed risk. Nothing in the way NPL markets and securitisation are developing guards against these risks, and it is therefore unclear how linking a variety of financial firms to distressed debtors will bring about a more stable financial sector.

Second, there are evident ethical and political reservations not only around debt, but also around the additional rounds of financialisation we are witnessing. If we are concerned about rampant inequalities, we should also be concerned that some sectors of the economy, which are making millions of profit each year in spite of their role in the financial crisis, are set to make more profits, this time on the back of distressed debtors.

The latter, who are already asked to pay for the consequences of the crisis (directly through wage and welfare cuts, and indirectly through the bailing out of large investment banks and widespread economic insecurity), are now forced to take on short-term credit, at times extremely expensive, in order to repay previous debt. Distressed debtors also tend to suffer physical and mental health issues, social stigma and exclusion, and find themselves powerless in the face of a well-organised industry that seeks to reap as many benefits as possible from their precarious situations.

Market Profits Over Debtors’ Rights?

Importantly, and this is a third major concern over the marketisation of bad debts, this imbalance between creditors and distressed debtors is likely to deepen in coming years, due to the effect that NPL market developments can have on debtors’ rights. Indeed, the very specific nature of non-performing loans means that their sale and securitisation, if it is to be profitable to investors, requires additional pressures to be put on debtors. As an industry memo explains, in the most extreme cases NPLs ‘do not generate any payments by the debtors that are made willingly’ and it is thus ‘incumbent upon the servicer to take active steps to resolve the NPLs and generate a cash flow’.

In plain terms, it means that debt collectors have to do everything in their power to extract payments from distressed borrowers. The kind of actions they can take – from letters and persistent phone calls to in-person visits, penalty fees and judicial actions, including home repossessions – is governed by regulations that differ widely from country to country and ultimately affect the profitability of an NPL transaction. There is thus a conflict of interest opposing on the one hand debtors, and on the other creditors and those working with or for them such as credit purchasers and debt collectors.

This appears clearly in the European Commission’s Impact Assessment (IA) of its new Directive on expanding markers for non-performing loans. According to the IA, the impact that different regulatory options would have on NPL investors and debt collectors ranges from quite positive (+) to very positive (+++). The impact on borrowers, however, ranges from quite negative (-) to very negative (—). In other words, the Commission itself expects that the proposed regulatory changes would have only negative impacts on debtors. In fact, the Commission actually seems to conclude that regulatory options are commendable, when they ‘produce a welfare shift from borrowers and supervisors to the benefit of investors and loan servicers’.

Overall, the Commission shows at best a lack of commitment to debtors’ rights, and at worse a willingness to favour creditors, debt buyers and debt collectors over European consumers and borrowers. This is particularly worrying given that debt buyers and collectors are known for ‘their unfair and aggressive practices towards distressed debtors—consumers, businesses, and even governments’. In Portugal, for example, debt collectors dressed up as Superman or Zorro reportedly used megaphones to publicly humiliate debtors and ‘persuade them to pay up’.

Alternatives

The cynical nature of the ‘bad debt industry’ which explicitly profits from the financial distress endured by a growing number of European households and businesses raises ethical and political questions which are being neither acknowledged nor addressed by EU policymakers. As the European consumer organisation BEUC highlights, ‘market actors who maximise their profits on the back of vulnerable consumers and businesses should not be supported, but should, instead, face restrictions’. Finance Watch, an NGO committed to making finance serve society, recommends that, at the very least, any proposition to expand NPL markets should include ‘high levels of consumer protection in debt collection practices’.

There are alternatives to the financialisation of distressed debts. For instance, given that banks sell NPLs at hugely discounted prices, concerned debtors could be given the option ‘to purchase their own debt at the discounted price, instead of it being sold to third-parties’. More efficient and socially relevant measures could also be taken to ensure that loans are only granted to those who can afford them (while others are provided with alternative sources of income), with clear terms and conditions that do not disproportionately prey on the most vulnerable.

Serious social issues such as over-indebtedness and precariousness will not be tackled through a blind reliance on ‘market efficiency’. Instead, we need social solutions, and broad democratic discussions on the role we want finance to play in our society.

More efficient and socially relevant measures could also be taken to ensure that loans are only granted to those who can afford them …

What loans? Bank “lending” CREATES bank deposits which are liabilities for fiat. However, due to government privilege for depository institutions, the liabilities are largely a sham* wrt the non-bank private sector.

The result is that banks can “safely” create vastly more deposits than they otherwise could if they were entirely private with entirely voluntary depositors.

The result of that is the banks are a sort of legalized counterfeiting cartel but arguably worse since the counterfeit must be repaid and with interest to create further injury.

*Since the non-bank private sector may not even use fiat except for mere coins and paper bills.

… (while others are provided with alternative sources of income) …

Arguably, ALL fiat creation beyond that created by deficit spending should be in the form of a equal Citizen’s Dividend – to avoid violating equal protection under the law.

Yes, hindsight is 20-20 and perhaps no one is to be blamed much for previous missteps but we are to blame if we cynically ignore the truth as we perceive it for mere pragmatism.

The way I look at the map is that where the courts/laws are debtor friendly then there are higher levels of NPL… Ireland would be the best example of that. There are those who can pay but they look at how it works and come to the conclusion there is nothing to be gained by paying.

Contracts might be similar (but definitely not identical) across the EU but with the different interpretations across the various countries it is a practical impossibility to securitise and investors who fail to see the difference between countries are at risk of losing out badly. Some have aleady lost out badly.

Different legal regimes are a complicating factor but not a bar to securitization of multi jurisdictional loans. At the end of the day it just affects the projected cash flows from different sub-pools and the resulting purchase price of the sub-pool. But, yes, you’d better get it right, or you lose money.

& let me guess, if all subpools are correctly valued then by some strange turn of events the value of the whole is higher than the sum of the parts? The math is of course so complicated that it is not worth explaining to anyone without a PhD in Math? Just trust the seller?

Whenever complexity is introduced then someone is making money on the extra complexity, if recent history is to be any indication then it is the middleman who benefits.

parasitism: def. relationship between two species of plants or animals in which one benefits at the expense of the other, sometimes without killing the host organism. … Intracellular parasites—such as bacteria or viruses—often rely on a third organism, known as the carrier, or vector to transmit them to the host.

What role for finance? It should be given the mandate to create a prosperous society at all levels or get out of the way. A mandate for well-being and equal benefits. So finance will have to have a big makeover. The securitization of debt sold to subsidiary spin-off “services” to make a profit from debt collection is not a makeover. It’s the finance industry elites dusting off their incompetent greedy hands and giving the dirty work to their henchmen. Only after they have literally killed the borrower, when the central bank itself runs out of money to bail them out, they will gradually scale down due to an unavoidable lack of “resources” – when they have to start paying interest to give money away. Serves them right. Because they mistook money for resources. How silly of them. We need finance based on real resources. On people.

Financilization of debt instead of forgiveness of debt is one of the three snarling heads of Cerberus. We are at the gates of hell, worldwide.

Thank you, Yves.

This is counter-productive from a macroeconomic perspective. At a time when foreign demand cannot be counted on as a result of the slow down in trade flows, the sensible thing would be to stimulate internal demand. Forgiving or restructuring the debts would free up all the money that is being used for debt service thus stimulating internal demand. Alongside “market efficiency”, there is the obsession with being a “good export nation” without recognizing the flaw in such a business model: over-dependence on strong trade flows. See Japan’s recent consumption tax hike.

Why can’t we dispense with all of the euphemisms?

This is usury.

Usury with a diabolical addition, the ability of the richer, the more so-called “worthy” of what is currently the public’s credit but for private gain, to steal from the poorer*.

Not only the ability but the NECESSITY unless one is willing to be forever priced out of, for example, the market for a home.

Up until recently an excuse for what is an inherently corrupt system was that it created good jobs.

With automation increasingly eliminating those, what remaining excuse is there for perpetuating it with mere patches such as a Job Guarantee to those dis-employed with the public’s credit but for private gain?

*e.g. See “redlining” where the ability of blacks to save was undermined by credit they themselves were not allowed to obtain. Now it’s just the poorest who aren’t allowed to join in the looting, being the least so-called “credit worthy.”