Even though this is a finance and economics blog, I haven’t written about the disruption in the repo markets. That is in part because the upset is not in any way, shape, or form like the 2008 period when banks were unwilling to repo even Treasuries to each other overnight because they were fearful another major dealer (say Morgan Stanley, which was on the verge of going tits up) would go the way of Lehman. I thought posting on it would feed the false narrative (which sadly is still kicking around) that the repo crunch is a sign of systemic stress, which it isn’t.

The second reason is that pretty much no one seems to have a clue as to why this is happening including most troublingly, the Fed. Perversely, the fact that the Fed is so clearly behind the curve is almost certain to make whatever the underlying problems are worse. Flatfooted central banks waking up to a problem and randomly hitting switches to try to make it go away is not only not a good look, but it makes the Confidence Fairy have a sad, which makes market upsets worse.

We’ll give a high level review of some of the major theories and why they don’t add up (and worse, look like special pleading by banks for regulatory breaks they don’t need) and will turn to an idea from John Dizard of the Financial Times (who regularly has great finds but is oddly buried by the pink paper by relegating him to a weekend wealth section column). Dizard argues that the big banks even with the apparent repo crisis make more money lending to the FX swaps market. This is consistent with big fish like JP Morgan’s Jamie Dimon whining about regulation rather than sounding at all worried.

Mind you, we are not saying there are not problems here. What we are question is whether they are being characterized properly and whether they could become systemic.

If Dizard is right, and Dizard is reviving and amplifying concerns raised by the Bank of International Settlements two years ago, the problem is in FX swaps and forwards, which amount to dollar lending but unlike repos, aren’t booked on balance sheet. That means that this area is a big blind spot for central banks; if you read the 2017 BIS paper, you can see they had to do tons of nitty gritty analytical work to come up with crude guesstimates.

Why This is Not 2008 Redux

We need to say this again and again: Banks are not afraid to lend to each other. There is no fear in the air. In 2007-2008, there were four acute phases of the crisis, starting with the implosion of the asset-backed commercial paper market in July-August 2007. There was a clear explanation as to why the ABCP market (which then was nearly half of the total commercial paper market) locked up. The biggest issuers of ABCP were special purpose vehicles including SIVs (structured investment vehicles) that used commercial paper as part of the funding for longer-term assets…which consisted significant if not entirely of subprime mortgage debt.

Things were so obviously not good that by September 2007, Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson was running around in what proved to be a failed exercise of trying to cobble together a private market solution for all of these SIVs, which were a problem for their big bank issuers. Even though these SIVs were supposedly off balance sheet and therefore not the responsibility of the party that set them up, the SIV investors (which included a lot of heavyweights) let the banks know that they had better act like they were responsible or said institutions would never to do business with that bank again. This sort of “not really off balance sheet” issue later came to bite the issuers of credit card receivables. The investors again made clear if banks ever wanted to be able to sell that paper again, they needed to eat some of the crisis-related losses.

The object of Paulson’s concern was clearly Citigroup, which had $400 billion of SIVs. Only later did we learn that Citigroup was dumb enough to have sold them with an explicit “liquidity put,” which meant the bank would finance the vehicles if the entity could not roll over its maturing short-term debt.

The point of this detour is there is no major category of debt blowing up and leaving investors and banks wondering who is taking big hits and therefore might not be a very good counterparty. Given that we have a lot of leveraged speculation against financial assets that are at sky-high prices, we could easily see some wheels come off in the not-too-distant future. But the repo market tsuiris is not the result of worries about bank or counterparty solvency. However, if the Fed doesn’t come up with better crunch responses than it has so far, its ham-handedness could make a bad situation worse when one develops.

Banks Blame Regulations

At a 50,000 foot level, it is not crazy to wonder if poorly-thought-out, far from comprehensive post crisis regulations might not have something to do with the liquidity crunch. The pre-crisis system suffered from what Richard Bookstaber in his classic A Devil of Our Own Design called tight coupling. That occurs in systems where activities propagate so quickly that humans cannot intervene quickly enough to halt the process.

What is needed in tightly coupled systems is to reduce the tight coupling. Circuit breakers that halt market trading when losses hit a certain level are one example. However, as Bookstabler described, measures to reduce risk in tightly coupled systems that do not address the tight coupling typically wind up increasing risk.

One of our big beefs about inadequate crisis reforms is virtually nothing was done to curtail derivatives, and we explained long-form in Chapter 9 of ECONNED why the crisis was a derivatives crisis, not just a bad housing loans crisis. The only measure taken, to move some derivatives clearing to central counterparties, has been regularly criticized as merely creating new too-big-to-fail entities. Note that had customers been required to post high enough margin to the CCP, that in fact would have cut into derivatives use. But no one wanted to mess much with this Wall Street golden goose.

Separately, we are not persuaded that this level of over-the-counter derivatives activity is necessary or virtuous. The really high margin, custom derivatives are used almost entirely for tax and accounting gaming. Many of the plainer-vanilla derivatives are used in connection with investments, or what it more technically called secondary market trading. More and more studies have found that the level of finanicaliztion in advanced economies is a negative for growth, and the amount of brainpower and resources devoted to secondary market trading and asset management is one of the biggest perps. So a simple missed reform opportunity would have been a transactions tax. It would have cut secondary market trading and in particular, the use of derivatives.

Oh, and derivatives are a big source of demand for repo funding. From ECONNED:

Brokers and traders often need to post collateral for derivatives as a way of assuring performance on derivatives contracts. Hedge funds must typically put up an amount equal to the current market value of the contract, while large dealers generally have to post collateral only above a threshold level. Contracts may also call for extra collateral to be provided if specified events occur, like a downgrade to their own ratings.17 (Recall that it was ratings downgrades that led AIG to have to post collateral, which was the proximate cause of its bailout.) Cash is the most important form of collateral.18 Repos can be used to raise cash. Many counterparties also allow securities eligible for repo to serve as collateral.

Due to the strength of this demand, as early as 2001, there was evidence of a shortage of collateral. The Bank for International Settlements warned that the scarcity was likely to result in “appreciable substitution into collateral having relatively higher issuer and liquidity risk.”

That is code for “dealers will probably start accepting lower-quality collateral for repos.” And they did, with that collateral including complex securitized products that banks were obligingly creating.

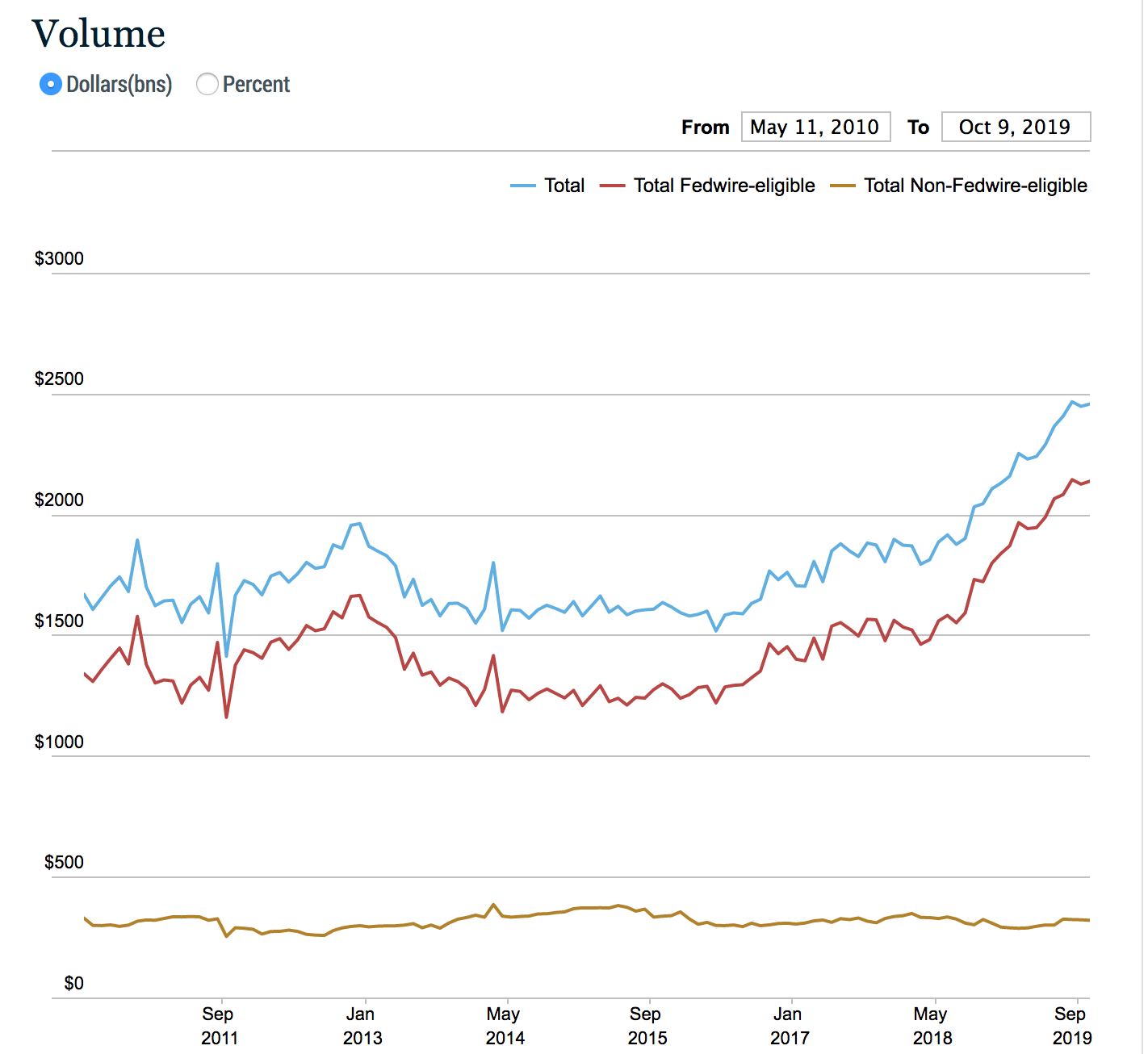

Notice how the use of repo increased starting in 2017 and more decisively in 2019 (the original New York Fed chart is interactive):

One way to look at this is that the Fed did undo the tight coupling by flooding the financial system with liquidity. The central bank for years has been trying to back its way out of the super-low interest rate regime it created, and has been finding that hard to do. Recall how the Fed lost its nerve in the 2014 taper tantrum.

And that increased use of repo roughly parallels how the Fed started shrinking its balance sheet, which is tantamount to reducing liquidity. FOMC minutes from March 2017 showed it planned to start trimming the size of its holdings by the end of that year. It actually started in October 2017.

Remember that prior to the crisis, the Fed had intervened daily in the repo markets from its New York Fed trading desk to manage money market rates. It abandoned that practice after the crisis and moved instead to paying interest on reserves when the banks were awash with reserves. It has not abandoned that approach despite also launching specific repo initiatives, although they were size limited, rather than using the former approach of doing what it took to hit the target rate.1

The initial repo market upset in September was quickly attributed to a series of demand for cash at banks, such as a corporate tax due date. The Fed being awfully slow to react was not helpful. And repo rates kept spiking up. Big banks started pointing fingers at rules that made them hold large liquidity buffers: “See, if you didn’t make us hold all this extra cash, we’d be lending to the market and you wouldn’t have this mess. So cut us loose.”

Former FDIC chairman Shiela Bair debunked this whining for deregulation (emphasis original):

So why didn’t the banks lend into the repo market?

Perhaps because they didn’t want to. Some of those caught in the repo squeeze were their nonbank competitors. As one industry insider with a top 10 bank told the Financial Times, “We have plenty of liquidity. We are just choosing not to lend it out overnight to hedge funds.” Or, harkening back to the 2008/2009 bailouts, maybe they thought that calming market squalls is no longer their responsibility, but that of the government. They were certainly quick to bash the New York Federal Reserve Bank for not being prepared to step in….

For its part, JPMorgan Chase says it was sitting on about $120 billion in reserves when the repo market ruptured. Dimon claims that it did not channel those funds into repos because regulators require that the bank maintain that level of reserves to prepare for stressed conditions, or worse, the bank’s failure. It’s impossible to know based on public disclosures whether Dimon’s interpretation of regulatory requirements is accurate. In any event, it does not seem unreasonable for regulators to want a bank with nearly $3 trillion in assets to keep $120 billion in ready cash on hand. The problem would seem to be that JPMorgan Chase — a dominant player in the repo market — was managing its liquidity too close to its regulatory minimums. With more ample reserves, it could have easily stepped in. Notably, Chase had allowed its reserves to drop by over 50% since the beginning of the year.

To be fair, it may be that the financial system needs more banking reserves to function properly. “Excess reserves”— that is, funds banks keep on deposit at the Fed that exceed regulatory requirements — are reported to be about $1.4 trillion. This sounds like a lot, and it is by historical standards, but it represents nearly a 50% drop from the peak in 2014. In its efforts to unwind its own balance sheet, the Fed may have drained bank reserves too far given the massive amount of cash the Federal government is pulling out of the markets to maintain its $16+ trillion-and-growing pile of public debt.

Bair’s take seems correct: the Fed drained liquidity too quickly. Izabella Kaminska pointed out another contributor: the Fed’s reverse repo facility:

It’s been a while since we checked in on what’s percolating through the mind of financial-plumbing specialist Zoltan Pozsar at Credit Suisse….

Here’s the gist from the opening of his latest note (with our emphasis, oh, and RRP stands for reverse repurchase agreement):

The FOMC should forget about r* for the moment and focus on Sagittarius-A* – the supermassive black hole at the center of global dollar funding markets.

The black hole is the foreign RRP facility, which has seen close to $100 billion of inflows since the beginning of the year.

The driver of these inflows is the curve inversion, and the longer the inversion persists the more inflows will follow. The trade war is also contributing to the inflows – given the inversion, as foreign central banks weaken their currencies they “buy” the foreign RRP facility and not Treasuries like in the past.

Foreign central banks are rate shopping… …and an uncapped foreign RRP facility is what enables that. Like the matter that enters a black hole, the reserves that are sterilized by the foreign RRP facility are gone for good – like the reserves “shredded” via taper.

However, I like the Dizard theory even better because it gives a direct explanation of why banks that had liquidity weren’t taking advantage of the opportunity to make some dough in the repo squeeze. That does not make Bair or Izzy wrong; they have important pieces of the equation, but are missing what looks to be a central driver.

FX Swaps and Hidden Dollar Debt

Dizard argues that the repo market spikes are symptoms of liquidity stress elsewhere, specifically in the FX and currency swaps markets.

Even though parties seeking to engage in currency hedges can engage in economically equivalent transactions using FX swaps, spot and forwards, or foreign currency repos, only the repo would be accounted for on the balance sheet of the financial firm. That means literally nobody knows how much in the way of FX swaps, currency swaps, and forwards are outstanding.2

The BIS was worried in 2017 about this hidden foreign currency debt, since the gross numbers were large and it was hard to infer much about it:

Every day, trillions of dollars are borrowed and lent in various currencies. Many deals take place in the cash market, through loans and securities. But foreign exchange (FX) derivatives, mainly FX swaps, currency swaps and the closely related forwards, also create debt-like obligations. For the US dollar alone, contracts worth tens of trillions of dollars stand open and trillions change hands daily. And yet one cannot find these amounts on balance sheets. This debt is, in effect, missing….

Focusing on the dominant dollar segment, we estimate that non-bank borrowers outside the United States have very large off-balance sheet dollar obligations in FX forwards and currency swaps. They are of a size similar to, and probably exceeding, the $10.7 trillion of on-balance sheet debt. On the other side of the ledger, as much as two thirds of the dollar-denominated bonds issued by non-US residents could be hedged through similar off-balance sheet instruments. That fraction seems to have fallen as emerging market borrowers have gained prominence since the GFC.

The implications for financial stability are hard to assess. This requires a more granular analysis of currency and maturity mismatches than the available data allow. Much of the missing dollar debt is likely to be hedging FX exposures, which, in principle, supports financial stability. Even so, rolling short-term hedges of long-term assets can generate or amplify funding and liquidity problems during times of stress.

It’s not as if all of the FX activity is hidden, but derivatives accounting treatment is way more forgiving than repos. As Dizard put it:

FX swaps contracts allow a non-US entity to exchange non-dollar cash flows for dollar cash flows. Thanks to the magic of derivatives accounting, only the variances in the relative value of the exchanged currencies (or “replacement cost values”) need to be disclosed by the banks mediating these transactions.

Let us stress that much the way credit default swaps were not bona fide derivatives (they were unregulated insurance contracts), it beggars belief that FX swaps are booked like derivatives. As the BIS explains:

These transactions are functionally equivalent to borrowing and lending in the cash market….

Why such a difference in accounting treatment? One reason is that forwards and swaps are treated as derivatives, so that only the net value is recorded at fair value, while repurchase transactions are not. Since the value of the forward claim exchanged at inception is the same, the fair value of the contract is zero and it changes only with variations in exchange rates. Yet, unlike with most derivatives, the full notional amount, not just a net amount as in a contract for difference, is exchanged at maturity….

Yet, despite this basic equivalence, the amounts borrowed through swaps and forwards never show up on any balance sheet while those related to repos do.

Recall that Shiela Bair quoted a banker saying that his bank had lots of liquidity but elected not to lend it out overnight. Dizard points out why they wouldn’t bother: they could make more money lending in the FX swaps market:

Why have the Fed’s large interventions since September 17 not calmed the money markets? Perhaps it is because that liquidity is being sopped up by the demands of the FX swaps market.

Ralph Delguidice, a money market observer and global macro strategist at Pavilion Global of Montreal, points out that for a yen/dollar FX swap, “a dealer receives a total of about 230 basis points for what is a synthetic yen-dollar repo. That includes the three-month dollar Libor rate, the negative rate on Japan Libor, a charge by the dealer called the ‘basis’, and the negative yield on the JGBs which are the best place for the dealer to park the yen they receive in return for dollars.

“Compare that to dollar repo which was 190 earlier this week, and Treasury bills, which are about 150. You can see why the dealers are incentivised to lend dollars in the FX swap market rather than the domestic money market.”

Now of course this raises the question of why the FX swaps market, and specifically dollar-related swaps, are in demand right now. Part of it is that the dollar dominates these markets. As the BIS paper helpfully explains:

The dollar reigns supreme in FX swaps and forwards. Its share is no less than 90% (Graph 2), and 96% among dealers (Table 1). Both exceed its share in denominating global trade (about half) or in holdings of official FX reserves (two thirds). In fact, the dollar is the main currency in swaps/forwards against every currency.

Financial Times reader Stimpy put the problem in more colloquial terms:

The point of the piece (and the BIS as well) seems to be that non-US bank USD lending has exploded (12T) and that those lenders are sourcing some (~1 1/2T) of the USD they need to fund the loans in the wholesale FX-swaps markets at huge maturity mismatches. The currency risk is nil, but the rollover risk is huge as demand for USD crowds out other borrowers, like repo, because swaps pay more and get better accounting treatment.

We still have the question of why the apparent increased demand for dollars. Is extra hedging going on due to tariff tantrum worries? Brexit wobbles? Readers who have insight are encouraged to pipe up.

In the meantime, Dizard believes that the FX swap cash demands could rise to being a serious issue, particularly since liquidity dries up around year end:

But the FX dealers and the borrower-counterparties can get spooked even more easily than repo market participants. As Delguidice puts it: “On the 23rd of December they will be concerned they have to roll over and they get a dial tone. Your risk manager is on line two and he wants to talk to you.”

Cynical people working for the dealers and regulators believe that the C-suites of very large global banks would use such a panic to induce the Fed and Treasury to push through a loosening of regulation and lifting of mandatory charges on capital.

So if and when an FX swaps crisis arrives, expect the demands for regulatory waivers to get even louder. But as we pointed out, they would just amount to yet more stopgaps.

_____

1 Warren Mosler thinks the Fed senior staff is likely well aware of these issues and said historically, political appointees would constrain action.

2 We discuss only FX swaps, which the BIS treats as currency exchanges of less than a year; longer than a year is a “currency swap”. The BIS paper also contends that FX swaps are generally used for trade and currency swaps, generally for investments like foreign bond purchases. However, it would be nice if practitioners piped up, since to fully hedge a foreign currency bond, you’d need to do swaps or forwards to cover the interest payment, and the nearest two would be in less than a year, putting them in FX swap terrain. I also wonder how much these instruments are used for short term currency speculation. Forwards certainly are a staple on currency dealer desks, and most multinationals have for over a decade been treating their Treasuries as profit centers, meaning they get to speculate too.

So two comments. One supportive of your thesis, and one which tends to contradict.

Its not true to say there is no cost to fx swaps and currency swaps. Leverage ratio denominator is the cost/constraint. But its definitely true that short dated fx swaps (below one year) are very cheap in LRD. This is not true for currency swaps. They are expensive in LRD terms.

The problem with your hypothesis is that there is no evidence of an uptick in costs for the fx swapping dollars to obtain them. That uptick is common and particularly so over year end and quarters end. But this doesnt appear to have happened this time. Yet.

Instead I would point you to this, which I think you might have had in Links

https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2019/08/22/1566491938000/There-s-a-black-hole-in-the-dollar-funding-market/

JPM may also be an important element. There was a significant shift in their balance sheet. They appear to have put more reserves to work – probably owning bonds.

Don’t straw man what we said. We never said there is no cost. We said the principal amount is not booked, only the variation, which the BIS estimates at zero at the times the trade is booked and 3% on average over time for FX swaps, 6% for currency swaps.

I didnt mean to straw man, and I don’t think I did.

No. I mean cost in terms of capital, or regulatory capital, or any arithmetic constraint limiting the total amount of business which can be done. In the case of off-balance sheet instruments, one of the two constraints is the Leverage Ratio Denominator or LRD. Banks are required to stay within a max LRD, and most weakly capitalized banks are constrained in the availability of LRD headroom. So you would avoid doing trades which are heavy users of LRD. OTC derivatives all use LRD although cleared transactions use less (from memory). Short fx swaps, (less one than one year) are pretty cheap in LRD. However swaptions, interest swaps and definitely currency swaps are very heavy in LRD use.

The figures you are quoting is (I think) effectively “in the moneyness”. Or the net exposure, where gross exposure is the “headline” number. I’m not sure I would think of that as the “cost”. I suggest cost is better defined as “opportunity cost” or constraint on unit of marginal business.

https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs270.pdf

Currency swap is usually a short for cross currency swap (xcy swap). I.e. you swap notionals at the start, then interest payments on the notionals, and swap the notionals back. So you cover both FX and IR risks.

FX swap is just two forwards (in extremis the near forward being a spot). Only FX risks matters (the IR is fixed by the implied FX forward rate).

No, that isn’t correct either. As the BIS states, there are plenty of swaps that are mismatched because the hedges are rolled monthly or on some other periodic basis. The rollover risk is much greater than the FX risk.

This was in response to your footnote two.

Currency swaps are not just “longer than a year”. They are interest + notional.

FX swap = two forwards on the same notional. Usually (for a number of reasons) < 1year, but in theory can be longer.

Currency swap = two principal exchanges (i.e. the FX rate is exactly the same for the first and final exchange) + a stream of floating interest on them in between.

BIS makes the same point (currency swaps are interest + notional) on page 2, in the "Accounting treatment, data sources and gaps" section, third sentence, first para.

FX swaps are rolled, by their short-dated nature.

Currency swaps by buy side are not rolled, as they are bought as a perfect cashflow hedges matching the dates and cashflows perfectly (which is their whole point). The only case there is if the underlyign debt is callable, and very likely to be called, then the investors may do the currency swap till the call date.

One doesn’t really use fx swaps for fx speculation. Generally they are for funding. Similar to a repo you buy spot and sell forward or vice versa. So if funding a mex peso position, one would borrow dollars for the month, and then buy pesos and sell them forward one month. Peso borrowing requirement met for 1 month. Then you roll for the next month. You can go out to 1 year on fx swaps, but beyond 1 year there is no liquidity and the regulatory costs in LRD start to become material. Currency swaps are very expensive in terms of credit risk too, because the position can go deeply into the money, and margin-ing/netting becomes an issue.

FX swaps ARE used speculatively for short interest rate speculation in markets where short rate contracts like eurodollars are unavailable. So if you want to bet on TIIA or Brazilian one month, one might use fx swaps to do it.

So pray explain ETFs and ETNs that allow you to bet on currencies. If there are retail products, there are almost certainly institutional products and institutional strategies. In addition, I’ve personally had multinational clients who lost a boatload on currency speculation in their Treasuries. The speculative uses may be minor relative to the uses for hedging trade transactions, but they most certainly exist. And well-established mechanisms like a carry trade are a currency bet, that you’ll be able to unwind the currency component and still have a profit due to cheaper nominal funding in the borrowed currency.

So you could use fx swaps to bet on currencies. But there is no need to. An fx swap is just a forward transaction. So a combination of the fx spot and the forward. A dealer will take a spot reference and then quote the points on top to get the fx swap. But if you want fx exposure, you can just trade spot and your custodian/prime broker book the fx to your fx account. Any interest will be credited idc. If you have a bad custodian you might be better off trading the fx swap rather than spot cos the interest rate might be better. But spot is (marginally) more liquid and generic than the forward, and you dont have to worry about novations or netting when exiting the trade.

Im sure the ETFs and ETNs will use fx swaps to manage their fx exposure. Im not sure its a great way to get fx expoure compared to using fx futures. They charge fees. Still the fees are small compared to fx vol so I suppose it doesnt really matter.

When I say one doesnt really use fx swaps for fx speculation, what I mean is dealers dont. Consider the tenor? Would you pick one day, one month or 6months? Which forward date makes sense? And how liquid are longer dates?

Rather you will find everyone in a dealing room trading instruments with fx exposure will use fx swaps to manage their fx funding requirements. Say you are trading Mexican Bonos? You need pesos to run that position. Rather than borrow in pesos, you will ask your $ funding desk for a rate on (say) 1w dollars. Then you enter an fx swap for 1w pesos. When one rolls off the other will roll off too. So everyone trading any fx exposure in fixed income (or equities) will end up use fx swaps.

Now consider a client who wishes to have EUR exposure. They will probably just buy a EUR government bond. Their position is a package of both EUR interest rate exposure and EUR fx exposure unless they fund their position in EURs as well. Voila, all the EUR exposure you want, and no pesky rolling fx swaps. You can have your face ripped off with market moves without ever touching an fx swap, or rolling it.

On another note, I saw this. I havnt read it. But Zoltan Poszar made an excellent call on this before.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-11-11/this-is-why-the-repo-markets-went-crazy-and-why-december-could-be-even-worse

Ahem, you are really misrepresenting the point. All the parties I mentioned are not dealers. And I’m not current on who is taking the FX risk for the ETFs, but pre-crisis, it was hedgies, not dealers.

Dealers (and I’ve sat on the desk of major currency dealers twice in my time) tend to take very short term bets. The people who are taking more point of view bets would be financial speculators like global macro hedge funds, the multinational Treasuries I mentioned, and various institutional investors who are taking a point of view on currency every time they make a foreign investment as to whether or not they hedge it.

Pulling rank, i ran an fx desk for a large dealer for a short while although i am more an interest rate guy. i think of fx swaps as rate instruments run by fx desks. The rate component is implicit in the deviation from the spot price. The spot component is an order of magnitude more volatile than the rate component.

Its true dealers tend to take short term bets. Its also true that their bets are small compared to the clients. But all positions being funded in a bank are generally funded using fx swaps. Spec and hedges. Fx swaps are a basic treasury tool. Very basic.

I have also been a position taker in various Asset Management firms. I can’t imagine a real money firm using an fx swap for spec. They might be used to fund leveraged positions where real money firms run hedge funds or absolute return. I can imagine (and have executed for them) hedge funds doing it . But it really isnt the main way fx risk gets taken.

Yes i agree that treasuries are more likely to use fx swaps to take risk. But thats cos they throw a lot of these around. Most treasury trades are not to take risk but to de-risk and finance.

I think Im explaining this badly and should probably shut up. Vlade’s explanation was very clear.

The one substantive point i made that i would like to emphasize is that i have seen no weird or outsized moves in either basis swaps markets or the forward points in any major fx swaps (to my knowledge). That doesnt support Dizzard’s point. Its possible that this demand couldnt be expressed for some other reasons but it seems troublesome.

Its not the funding of the spec positions for global macro (or even real money fx positions) which will matter. All small potatoes. Its the funding of all the fx on bank balance sheets. Fx swaps finances most of it. Spec fx positions will be a relatively small element.

Any instrument can be used for speculation. But at the same time, you use the most appropriate instrument.

FX swap is not really a derivative. It’s two zero-coupon loans, and you need to find the cash to do it (which is why real bussinesses uses that, as if you have the cash in the account, and it would be just sitting there anyways…)

If a liquid futures markets exists, there’s little point in speculating using FX swaps – it’s more expensive funding-wise (you need to fund the principal, not just the margin). I could happily trade millions of FX exposure with a few 100k assets in my account. I could not do a single FX swap with that money in my account as I’d be way below the threshold for the banks.

The only rational reason why someone would want to speculate on say EUR/USD with FX swaps would be that they wanted to do it today, and had a relationship that would sell them the FX swap, but could not establish the future as quickly.

Where there is no real derivative market, or is very illiquid, FX swaps/forwards etc. is what one would have to do for speculation.

Exactly. I am embarassed to be so bad at explaining something.

Not really understanding this so perhaps this is way off base –

Is it possible that some players in the financial markets are gaming the Fed ?

Thank you for the great round up. Risk regimes tend to be backward looking, and everyone is using a 2008 lens when analyzing repo turmoil. It’s good to see the distinctions drawn; and to highlight how this is, at the moment, more of a P&L event than a systematic risk.

I think the refrain from the usual suspects that there was $ available but it was constrained by regulation is a half-truth. Bank balance sheets are massively constrained by capital and liquidity buffers; but these regulatory requirements haven’t prevent banks from growing their balance sheets over the last 3 years.

Imho the “liquidity” shortage of mid-September was driven by the nature and timing of the repo market; and the costs and constraints that arise from intraday liquidity.

The day-to-day supply and demand drivers of the repo market, be they coupon settlements or corporate tax days, were neither unexpected nor the likely suspects for such violent price swings. But one needs to move away from “markets” and towards geopolitics to note the other, larger, and unexpected driver in mid-September: the attacks on the KSA facilities.

In response to these attacks KSA had to withdraw $ from US banks. Mercs aren’t free and other such considerations coming into play.

This left a huge intraday liquidity hole in one banks profile. Typically a bank pays a daylight overdraft fee to borrow intraday from its clearing bank. The violence of the move in rp suggests that the lack of liquidity was significant enough to outstrip p&l and fee concerns. The bank likely thought it may break through it’s intraday lines and not be able to settle anything.

To some extent the market worked. HQLA rp is an easy and fast way to raise intraday liquidity. In someways the market failed. The violence of the move, and the subsequent fallout, suggests that dealer balance sheets and system leverage are so high that excess capacity is hard to deploy rapidly.

I do agree that there is a huge off balance sheet fx swap market. But it’s hard to pin point swaps as the driver for rp, or vice versa. The users of swap dollar funding will also use repo; and a lot of that swap usd is ultimately raised via repo.

The explosion in fx swap financing is driven by Central bank policy decisions(mistakes?). With local interest rates negative, Japanese lifers and European concerns need dollars to buy dollar assets in their search for yield.

Maybe in our search for the next crisis event, we are like the frog in a pot of water set to boil. The system isn’t going to fail, because it has already failed. Negative rates and the hyper financialization they drive are the crisis. The repo event is just one bubble in our boiling pot.

Perfect last paragraph. “The System isn’t going to fail,

because it has already failed”

“The Repo event is just one bubble in our boiling pot”

So why are rates so low? Bc of inequality. If the rich have all the money and are concerned with staying rich, I.e. they want super safe investments, they want sovereign bonds, which they bid for, driving yields negative. The game monopoly shows what happens late in the game as all the money accumulates to fewer players… the losers have no money and are driven out to the sidelines, with nothing to do but watch the rich, still active players. Like our homeless.

Europe is more serious about austerity, only their remaining stabilizers keep homelessness at bay… but not in Greece, Italy on deck.

Europe is on the gold standard, pelosi wants us to do the same, witness pay go. Of course not for mil or deep.

The more we allow monopolists (what Buffett speaks approvingly as having a moat) to acquire all wealth the lower yields will go. Just like allowing private banks to use our sovereign power to create credit and guarantee deposits no matter how stupid their lending…

Only massive fiscal deficit spending will get money into the hands of spenders. Only ending monopolies and taxing the rich will reduce inequality.

Bernie?

i would agree. Rates are low to reinforce global inequality. That said, I don’t believe low rates always drive inequality, but they are currently a policy tool of imperial coercion.

The USD repo market is the fundamental brick in the ZIRP leverage pyramid that drives down the value of labor and savings, and buys out an exploits the global commons.

I think this article does a good job of explaining the geopolitical effects of ZIRP

https://thesaker.is/qe-paid-for-a-foreign-buying-spree-developing-countries-hurt-the-most/

Tbh I don’t think massive deficit spending will help. We already run massive deficits. But redirecting that spending would make for a better world. Meaning let’s not keep the guns and butter, just the butter.

I do believe that funding spikes and blown out year-end cross currency basis swaps are indicators of massive leverage in the system. But they aren’t harbingers of crisis. I abide by the previously stated notion that the system has been in perpetual crisis/failure for over a decade; and tptb intend to keep it so for as long as possible.

I’m not a catastrophist but do think that de-dollarization is the only scenario at the end of the road. We may get there faster via some catastrophe, or via the persistent weathering of our obsolete institutions. But I do think this end would be a well deserved catastrophe for that American way of life built on extraction and rent.

I am quite sure my comment is a vast over simplification but it is probably worth getting shredded over regardless.

If in fact foreign entities hold 68% of USD after the Fed has pumped massive amounts of currency into the global system, it seems to me we have a mismatch of global USD money market requirements against reserve requirements based on the domestic market. Could it be that the Fed has created a monster it no longer controls via the systemic money market banks?

https://deep-throat-ipo.blogspot.com/2019/10/repo-acalypse-now.html

This was linked in a previous comment section. I think there are a lot of dots connected in this theory that should not be, but if you discount the ominous motivations of foreign actors, the author does lay out a plausible scenario in which the Fed is no longer in the drivers seat.

“The Accountant” gets his numbers from the source and applies logic and potential motive and comes to conclusions that seem far fetched, but not impossible.

Another potential reason for repo madness comes from Wolfstreet, and this could be just as much of a reason. As Yves says, the FED is running with one eye blind and can’t see much out of the other. Their concern is to make sure the richest of the rich never have a nanogram of financial pain, lest that pain be leveraged into a ten ton boulder that crushes the peasants.

https://wolfstreet.com/2019/11/06/whats-behind-the-feds-bailout-of-the-repo-market/

Man, that’s a huge company isn’t it. Trillions in funny money being swapped back and forth so this company can pay “management fees” and profits to a hedge fund.

This gigantic operation has zero employees. It’s pure fraud in my book and should not exist in a just world. Sucking on the government tit for billions floats a lot of mega yachts, but hey this is modern capitalism, and these criminals will tell you they work hard for every penny they earn.

It’s as if there are financial IEDs in every corner of the financial market, ready to blow at the slightest hair trigger.

Bernie Sanders: The business of Wall Street is fraud and greed.

This is why I have been loath to write about this topic. There is a ton more noise than signal and too many people are getting distracted by noise.

I hate to tell you but that analysis by Wolf, while it took a lot of work, does not give any new insight as to what is going on. This is one pretty small by market standards participant, and Wolf has no idea how representative it is. Another issue is that the REIT could easily have engaged in more repo “churn” by being forced into shorter borrowing tenors (like a lot more overnight repo when it used to repo for a week, Wolf points out the amount of overnight repo at quarter end, which would have been dressed up if the REIT thought it important to do so). The Fed charts shows demand for repo rising…..the REIT could have moved to shorter average tenors for reasons of price.

Big banks and even the Fed have already said there are non-bank repo users who aren’t getting liquidity. Demand from non-banks exceeds supply. So giving a particular example really doesn’t say much. The person in the FT attributed demand to hedge funds. They have few employees too. This REIT is acting like a hedge fund. So?

I don’t mean to sound critical of Wolf but of what people are making of his post. Wolf gave a window into a particular party that is a heavy user of repo and therefore would be inconvenienced or even potentially take losses due to the repo crunch. But this sort of player taking a hit is an effect of the repo squeeze, not a cause.

We are still back to the question of why are dealers withholding liquidity. The short answer is the Fed tightened too fast in light of the new rules; a longer version is to the extent liquidity is scarce, dealers find it more attractive to support the FX swaps market than the repo market, particularly since the repo market is ultimately a Fed problem, and they will eventually have to Do Something.

“I thought posting on it would feed the false narrative (which sadly is still kicking around) that the repo crunch is a sign of systemic stress, which it isn’t.

“The second reason is that pretty much no one seems to have a clue as to why this is happening including most troublingly, the Fed. Perversely, the fact that the Fed is so clearly behind the curve is almost certain to make whatever the underlying problems are worse”

This seems contradictory. If the Fed is basically clueless, and simply throwing money at the problem because they are being manipulated or simply out of ideas, that suggests the derivatives etc markets are effectively out of control, and in such an environment the hubris among market players will expand and liberties will be taken to lead the markets further into complexity ad absurdum, which over time will make the system ever more fragile.

It seems to me the greatest danger here is the threat of a collapse of faith in this system, should this precipitate another market collapse. Many of us after 2008, after the bailouts and Obama handing the keys of the kingdom to big finance, said the next market collapse will be worse than 2008. This is like children who never grew up, pushing boundaries ever further because they can, backstopped by a system that basically says the only good is making more money, no matter the consequences.

No, this is not a systemic crisis or even systemic hiccup because none of the major bank players are having solvency or credit issues. This is not contradictory.

The stress is taking place due to non-bank players and perhaps some smaller banks not having access to liquidity. We had lots of quant hedge funds blow up during the crisis. That was a sign of how bad the market dislocations were, but due to post LTCM changes, didn’t threaten the banking system.

There is no sign of any danger to the core plumbing of the banking system. Banks are absolutely not afraid to lend to each other. They have made clear they are choosing not to, with some blaming regulations.

Now a real shock (serious credit losses somewhere) on top of this inability to move liquidity around would likely AMPLIFY a crisis if the Fed does not get its arms around the problem.

More generally, the focus of the post-crisis reforms was to move even more risk out of banks onto non-banks. The one obvious fail, as mentioned, is in creating central counterparties for derivatives which are clearly too big to fail entities but no one has any formal responsibility to backstop them. Like Fannie and Freddie, they most assuredly would be salvaged in a crisis, but it would be messy and a lot of people would reasonably be upset.

The most likely culprits for a crisis are Eurobanks and Chinese banks. In the US, the losers if we have major dislocations are much more likely to be investors, such as the major fund complexes (BlackRock), life insurers, and public pension funds, and other non-bank entities, which could still really whack the economy without causing a conventional banking crisis (Fed and FDIC having to rescue and/or resolve a lot of banks). One thing I have to look at again is ETFs. They were the subject of a lot of handwringing a few years ago as a possible vector of systemic risk. BlackRock is the big kahuna in that business.

I wish I had access to the repo market and could borrow billions for one day, every day for ever.

I would use the money to buy up assets. That would be a perfectly safe investment as long as the Fed continues it’s policy of rate suppression and QE.

I would be fantastically rich. I would among the 1%.

And I would get richer and richer the more and more I borrowed.

Count me among those who don’t really understand all that’s involved in this article. But IMO these wishes sum up what may be happening: Fewer and fewer big concentrated players with fantastically more assets due in good part to the Fed’s very very long rate suppression and QE. The amount of mal investment capital is hugely larger than it was in 2008. The players are adapting to extended, forever QE and rate suppression and altering their behavior because of it, because the know it will continue essential forever.

It’s a new world in what we used to call investment.

I still think that Saudi losing a large percentage of it’s oil production at about the same time of the crunch is not coincidental.

Saudi loses a big chunk of their ongoing $ income. The kingdom is a giant welfare state for guys in solid gold yachts. They get bombed and all of the sudden there is not enough dollars to support all of the princes.

Just trying to get back to normal $ flows to SA would require sales of lots of other stuff, in other currencies, all headed back to get more dollars to keep the princes in gold yachts. This is of critical importance to the regime in SA. Cut off the dollars and the regime falls quickly. An existential threat to MbS, who remember, just a few months ago, took a lot of hostages and only let them free after the paid billions in ransom.

Softbank?

I also believe that SA has been borrowing ahead against oil revenues that it is now trying to IPO.

YMMV

First, like others I admit I am over my head in this matter, but a couple of thoughts:

1. This reminds me of the old poker adage: If you don’t know who the sucker is at the table, its probably you (the Fed).

2. Since the massive increase in liquidity initiated by the Fed has not stopped the surge in repo rates, I suspect it is not a plumbing problem, but an entity or entities gaming the system problem i.e. hedge fund, bank or government. I would be tempted to let the repo rates remain high for a period of time and see who blows up, something like the Long Term Capital Management collapse in the late 90s. I admit this action would have some risks.

Since the political power of financiers and rentiers is so vast and the state of financial markets is so detrimental to the health and well-functioning of the real economy and society in the broadest terms, and since any chance of reforming the markets is so remote due to a degree of complexity that far exceeds the kind of common understanding needed for democratic action, shouldn’t they all simply be swept away?

And wouldn’t a collective system truly responsive to the democratically expressed will of all the people be preferable? (I know. Dream on. But it’s no more ridiculous than imagining that some tweak to the system might do the trick, because truly effective tweaks appear to be every bit as impossible as a full-boil revolution.)

Wolf Richter has his own theory, involving different class of duration-mismatch-based speculative arbitrage:

What’s Behind the Fed’s Bailout of the Repo Market? | Wolf Street

Long story short: A bunch of hyperleveraged speculators arbitraging the low rates in the repo market had that blow up in their faces and got bailed out. From Wolf’s analysis of one such actor, a REIT:

AGNC lists $106 billion in total assets on its 10-Q filing with the SEC. Of them, about $93 billion are mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddy Mac, and Ginny Mae. The second largest asset are about $9 billion in receivables from reverse repos. Plus, it shows $1.2 billion in Treasury securities, and some other things in smaller amounts.

But the company has only $10 billion in equity capital. So how does the company fund these investments?

On the day of June 30, AGNC owed $86 billion to the repo market, out of $96 billion of its total liabilities. In other words, nearly all of the cash to fund its investments comes from the repo market.

During the six months period through June 30, the company cycled nearly $2 trillion with a T through the repo market, borrowing short-term, paying back the required amounts when the repos mature, and then borrowing again, constantly rolling over the increasing pile of short-term debt.

So over the first six months this year, this company has cycled through nearly $2 trillion in repos. This is up from $700 billion over the same period last year.

Note I forward the above link/comment/snip to Yves, she wasn’t buying, hope she doesn’t mind my posting her reply here:

This doesn’t prove anything. It could have changed the tenor of the repos from say a week to a day due to the market stupidity. The turnover is an effect, not a cause.

I agree REITs shouldn’t be speculating like this but [Wolf} is looking in the wrong place.

Wolf has given some color as to who the repo users are but this does not explain why the big banks are not willing to provide liquidity to them. Simply saying their demand went up isn’t sufficient as an explanation, since the big banks freely admit they are sitting on liquidity.

Why did the Fed even bother with repos when there is no problem with the financial plumbing?

Would the big banks, sitting on their piles of cash and going on what can be construed as a capital strike have ulterior motives, like crashing the REITs and hedge funds and then picking up the peices for pennies on the dollar? Its not like the big banks wouldn’t be true to form and practice fraud and greed on those even a step below.

So there was some work done on this by the Andolfata and Ihrig. They suggest the culprit is “living wills” and the intraday liquidity requirement.

I’m not sure, but its a coherent theory explaining why you will need a positive excess reserve balance. However I dont think this on its own explains what happened to require an extra 300bn of Fed balance sheet. I guess one should distinguish between a friction which ensures that banks will warehouse “excess liquidity” given the new regulatory regime. Contrast that with why the situation can suddenly shift. This paper gives thoughts on the former without addressing the latter. So this might explain why banks with excess reserves might not lend them via repo.

One thing which is clear, is that the change was probably at JPM. They were the bank reporting a $300bn shift in their utilisation of excess reserves. However that doesnt really prove it was their “fault”. They will act as prime broker/custodian/US correspondent for god knows how many international clients.

I dont really get what happened, but I am all ears and very keen to find out.

https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2019/april/fed-standing-repo-facility-follow-up

So if banks have the liquidity but are not using it in circumstances the Fed deems critical, what’s the point of having private banks? After all the Fed is paying them a lot of our money to have all that liquidity. Why doesn’t the Fed nationalize them? Because until it does or until it figures out a different solution, it’s doing what it thought private banks ought to do.

The Fed is ultimately responsible for liquidity. It sets a policy rate, which is the Fed funds rate, and is supposed to add or drain liquidity to make sure that rate is in place. The repo rate spiking is a sign of Fed operational screw-ups, and they are still behind the curve, I can’t prove it, but IMHO the problem appears at least in part to them sticking with interest on reserves as their method for managing money market rates, when the repo blow out shows that doesn’t work very well when the Fed is tightening.

Warren Mosler has this to say early on:

So this is my current best hypothesis re what happened. Its full of holes and Im not completely convinced by it either but here goes.

1) You have a GFC.

2) Regulators respond in two ways. Flood system with liquidity (TARP QE etc) and then applying new regulations which require “living wills” and a new BIS risk framework.

3) (10 years later) You slowly remove “excess” liquidity – QT.

4) At some point, you find out that not all of the “excess” liquidity is excess under the new regime. The Fed had an idea that maybe 1.2trn was where they should tread carefully, but they were out by at least 250bn. I suppose that’s not bad considering.

5) Fed reverses course to resupply excess liquidity.

The “culprit” appears to be the intra-day liquidity requirements associated with the living wills. But I wouldn’t know. The guys who do know are the treasuries of the money center banks. In the past, when I have seen their comments, they had made the point that foreigners who were pretty much reliant on them for dollar funding, were constantly complaining at the limited availability of dollars, not the cost. The new regulatory environment constrains the amount any bank can supply them.

Of course, they could do things like raise more capital etc. But thats not really on the agenda.

I recommend the Bloomberg podcast on this subject. Posznar seems to know his stuff.

Jimmy Dore, Fed Secretly Bailing Out Banking System AGAIN!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XRQecD-Gopg

Way over my understanding too but this might be a good place to add this Jimmy Dore w/ Dylan Ratigan’s pop interpretation of this Fed/repo event and his take on what’s really behind Dodd-Frank and its coming into play here. Ratigan, if I got it right, is saying that the next big crisis can be handled completely behind the scenes, in the dark, Chinese capitalist style. Thanks to Dodd-Frank there’s no more need to go to the politicians with the dependant public support and con job as in 2008. If a tree falls in the forest and no one hears it did it fall? As there was never any write down of the trillions of toxic junk from 2008, the bubble was re-inflated and then some, inflation never appeared to winnow debts, the Fed would be in a seriously bad place handling the next crisis. Shutting up and acting behind the scenes is the last arrow in their quiver. Ratigan makes sense to me, as we are going full neo-feudal and public coffers are now private coffers why would anyone other than a handful of financial ruling elites need to know anything about how anything is managed?

I saw that Jimmy Dore episode and agree with you. I wonder what Yves thinks of Ratigan’s musings. Maybe he’s off base. Maybe not.

This claim is false. They did write down “toxic junk” as in CDOs. Nearly all of the CDOs based on asset backed securities went to zero. Moreover, subprime bonds also took losses on the average of 40%.

However, big banks were spared losses. They were allowed to play all sorts of games with their second mortgages (which they held on balance sheet) including modifying firsts and not the second when the second should have been wiped out before the investor-owned first mortgage was touched.

Interesting and perhaps the repo market ripple in the force explains why many mREITs took a huge dive over the past 6 months. Seems like a disruption in the repo market would be an existential threat to these firms’ “business model.”

One that I follow (Annaly Capital Management) tanked to lows not seen since the late 90’s, when we had a very different Fed and interest rate regime.

It could just be a coincidence … or not.

REITs have to give 90% of their profits to investors in order to keep their favored tax status, so I am not sure how hedge funds are the primary beneficiary here. Certainly many small investors including myself, full disclosure, use these REITs to reach for any kind of yield in a negative interest trending world.

After reading all the comments I’m still not sure what the proximate cause of the current repo crises is, though no one seems to dispute the point the Yves made that is not a result of big banks themselves feeling stress, well I assume Deutsche bank is feeling the stress of just about everything now, but that is not the trigger. It also seems likely the problem lies in how the unregulated derivatives market functions, which I’m still trying to wrap my head around. If I’m understanding it correctly at the core is the ability to find collateral to leverage and since the banks have naturally maxed out the amount of collateral they control, Jamie is telling the truth that regulatory constraints are limiting what they can do with the limited amount of collateral they have left, though I’m pretty sure he would be singing a different tune if it was his home and salary that were going to be on the line instead of tax payer money. Jeffrey P. Snider at Alhambra has been writing about how the Euro dollar market has been collapsing for a while now and how China is dependent on it for its dollar funding needs. I’m not knowledgeable enough to understand how this ties into Fx markets except that it does. To me it seems that environmental constraints, in particular cheap energy (oil) have increased the cost of doing business such that growth has slowed, this in turn has led to slower asset creation and thus less collateral for the derivatives market, which in turn leads to less funding (at a 100x scaling ? due to all the leverage), so leading to slower growth and so on. The credit markets have been growing at a much faster rate than the real economy since the 70s and the Feds QT only exacerbated the problem with collateral as did more distant decisions such as the short term profit motives in scaling up the inherently unstable nuclear reactors designed for subs instead of listening to the scientists designing these things and spending a little more time developing the inherently stable thorium based molten salt reactor they were developing, which could now be helping smooth the transition to renewables instead of costing us a ton of money and resources in clean up efforts. Thus it seems reasonable under these circumstances that the attack on the Saudi oil refinery had some role in the repo crisis, if not directly, then at least in the risk costs associated with the collateral. It also seems that we have just about collateralized everything to feed the beast including the assets in our corporations and government even our children through student loans such that we have this highly correlated monster that is so large that even the $120 billion a day (which just one days worth would be more than enough to solve our healthcare crises if fed into the front end, subsidizing no till organic fruits and vegetables, instead of the back end dealing with the consequences of poor diet) is still not big enough to calm the derivative beast. Finally it also seems the rising backlash to neoliberalism has to have some effect on collateral values, look what happened in Argentina and what’s going on in Chile, France, etc.

Yves is right. The stress is not among the big banks.

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-forex-swaps-insight/in-swaps-we-trust-disappearing-dollars-drive-currency-trading-dependence-idUSKBN1XO12U

Seems relevant. There is a chicken and egg question. But the lack of dollars internationally has been true for a while, and seems to be driven by (perfectly sensible) changes in banking supervision.