Yves here. Quelle surprise! Economic decline is a big driver of populist discontent in the EU.

By Lewis Dijkstra, Head of Economic Analysis Sector, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy, European Commission; Hugo Poelman, Senior Assistant, DG Regional and Urban Policy, European Commission; and Andrés Rodríguez-Pose Professor of Economic Geography, London School of Economics. Originally published at VoxEU

Support for Eurosceptic parties and the rise of populism threaten not only European integration, but peace and prosperity on the continent more broadly. Rather than attributing their rise to the individual characteristics of voters – such as age or income – this column takes a different approach. Using results from recent legislative elections to map the geography of EU discontent, it finds that purely geographical factors – chiefly, long-term economic and industrial decline – are the fundamental drivers of anti-European voting.

Support for Eurosceptic parties has soared in parallel with the rapid rise of the populist wave currently engulfing Europe. Discontent with the EU is purportedly driven by the very factors behind the surge of populism: differences in age, wealth, education, or economic and demographic trajectories. New research mapping the geography of discontent across more than 63,000 electoral districts in the EU challenges this view. It shows that the rise of the anti-EU vote is mainly the consequence of long- to medium-term local economic and industrial decline in combination with lower employment and a less educated workforce. Many of the other suggested causes of discontent matter less than expected, or their impact varies depending on levels of opposition to European integration.

The Growth of Anti-EU Voting

On 24 June 2016, citizens of the UK and the rest of the world woke up to the news that Britain had voted to leave the EU. Although many polls had predicted a tight outcome, the overwhelming expectation – including by most leaders of the ‘Leave’ campaign – was that Britain would vote to remain in the EU.

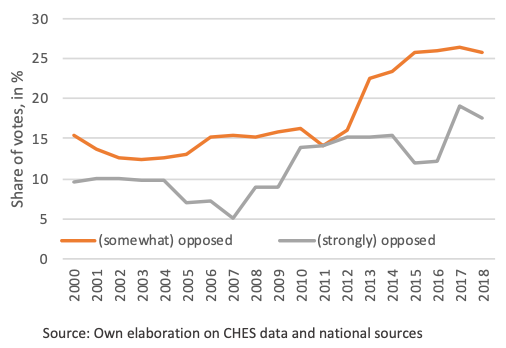

But the Brexit vote was not the first sign of growing disenchantment with the EU. The share of votes for parties opposed to EU integration, as defined by the Chapel Hill Expert Survey, has been steadily increasing over the last 15 years (Figure 1). The vote for parties ‘strongly’ opposed to EU integration grew from 10% to 18% of the total between 2000 and 2018. The same upward trend is observed when considering parties ‘somewhat’ opposed to EU integration: from 15% in 2000 to 26% in 2018. The vote against EU integration increased by almost the same amount in the EU without the UK.

Parties strongly opposed to European integration tend to advocate leaving the EU – as has been the case with the UK Independence Party (UKIP), the Dutch Party for Freedom, and the French Front National – or scaling it back to a loose confederation of states – as proposed by the Italian Lega, the German AfD, and the Hungarian Jobbik. Parties that are somewhat opposed to European integration, such as the Italian Movimento Cinque Stelle or the Hungarian Fidesz, want the EU to change substantially but do not necessarily advocate leaving the Union or turning it into a loose coalition of sovereign states.

Figure 1 Share of vote for parties that oppose EU integration in the EU-28, 2000-2018

What Determines Anti-EU Voting?

Researchers trying to assess the motives behind anti-establishment and Eurosceptic votes have mainly concentrated on the individual characteristics of voters, identifying them as “older, working-class, white voters, citizens with few qualifications, who live on low incomes and lack the skills that are required to adapt and prosper amid the modern, post-industrial economy” (Goodwin and Heath 2016). Individuals ‘left behind’ by the modern economy are much more likely to turn to or find shelter in anti-establishment political options: “such ‘left-behind’ voters feel cut adrift by the convergence of the main parties on a socially liberal, multicultural consensus, a worldview that is alien to them” (Ford and Goodwin 2017). Age, education, and income thus form the ‘holy trinity’ of the populist voter (Ford and Goodwin 2014, Hobolt 2017, Becker et al. 2017). As summarised by Los et al. (2017) regarding Brexit, “citizens who were older, or lesser educated, or socially conservative or lower paid, were all more likely to vote leave, while those who voted remain tended to be on average more highly educated, younger, earning higher incomes and more socially progressive”.

Our new research (Dijkstra et al. 2019) challenges these views, emphasising the long-term economic and industrial decline that planted the seeds of the current rise in Eurosceptic voting more than any other factors.

Mapping Euroscepticism

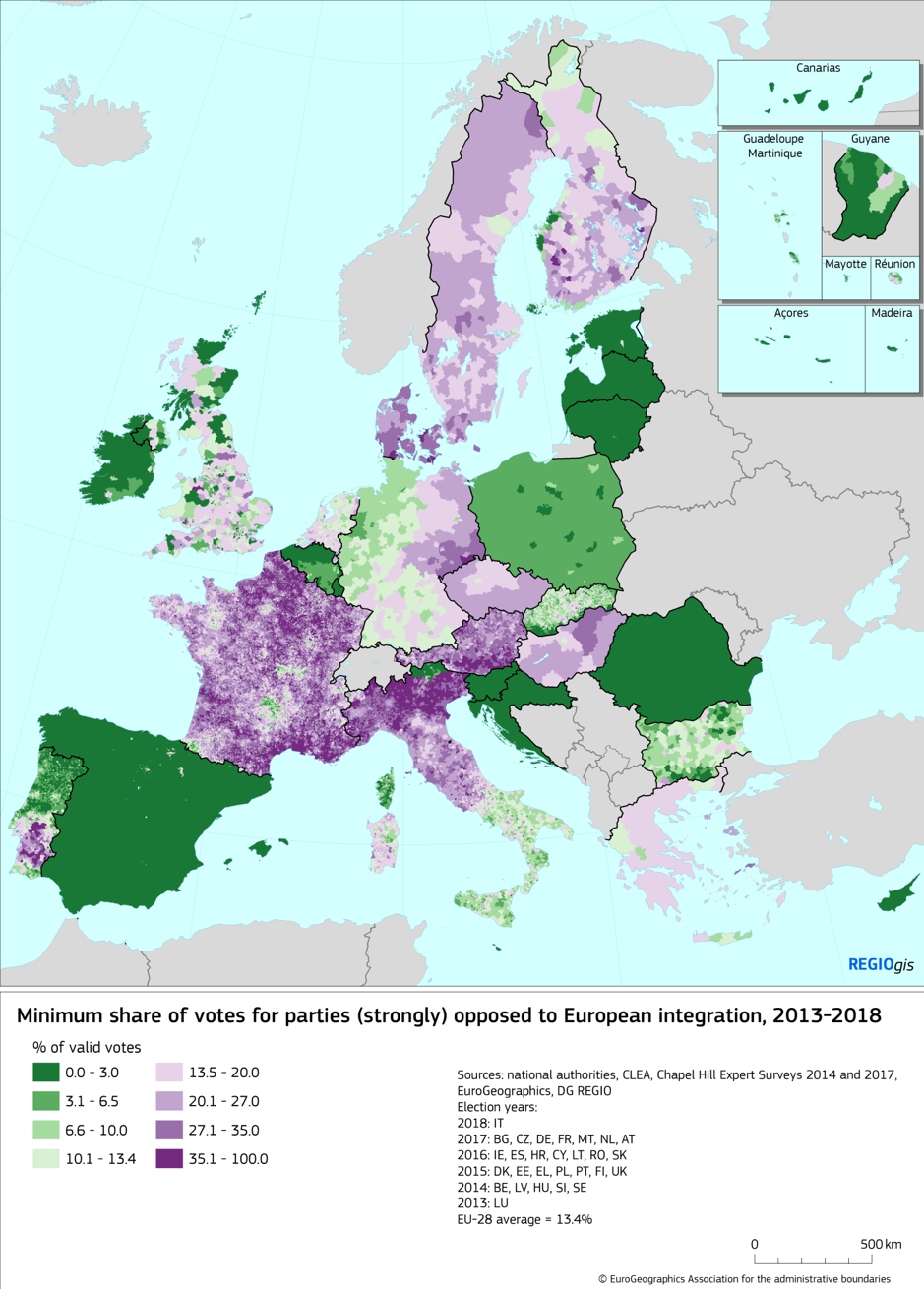

Our work proceeds by mapping, for the first time, the geography of EU discontent, using electoral results in recent national legislative elections,1 in a total of 63,417 electoral districts (or equivalent), covering all member states of the EU. The results show that in many EU member states, parties strongly opposed to EU integration have become a force to be reckoned with, having garnered more than 25% of the vote in three EU member states: Austria, Denmark, and France (Figure 2). Others, such as Cyprus, Malta, Romania, and Slovenia, have so far remained immune to the anti-EU wave. But these countries are increasingly the exception, not the rule (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Share of vote for parties opposed or strongly opposed to European integration, 2013-2018

Votes for parties opposed and strongly opposed to European integration are spread across many parts of the EU. Southern Denmark, Northern Italy, Southern Austria, Eastern Germany, Eastern Hungary, and Southern Portugal are hotspots of anti-EU voting. Rural areas and small towns are more Eurosceptic than bigger cities. The anti-European vote is far lower in Lille, Metz, Nancy, or Strasbourg than in the surrounding countryside (Figure 2). The same applies in East Germany, where the anti-European vote is far less prominent in Berlin, Dresden, or Leipzig, than in surrounding areas; the two largest cities in Northern Italy – Milan and Turin – stand against a large number of medium-size cities, such as Bergamo, Brescia, Cremona, Mantua, Pavia, and Vercelli, as well as smaller cities and rural areas. Northern and Eastern Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and the Czech Republic also have a strong presence of radical anti-European parties.

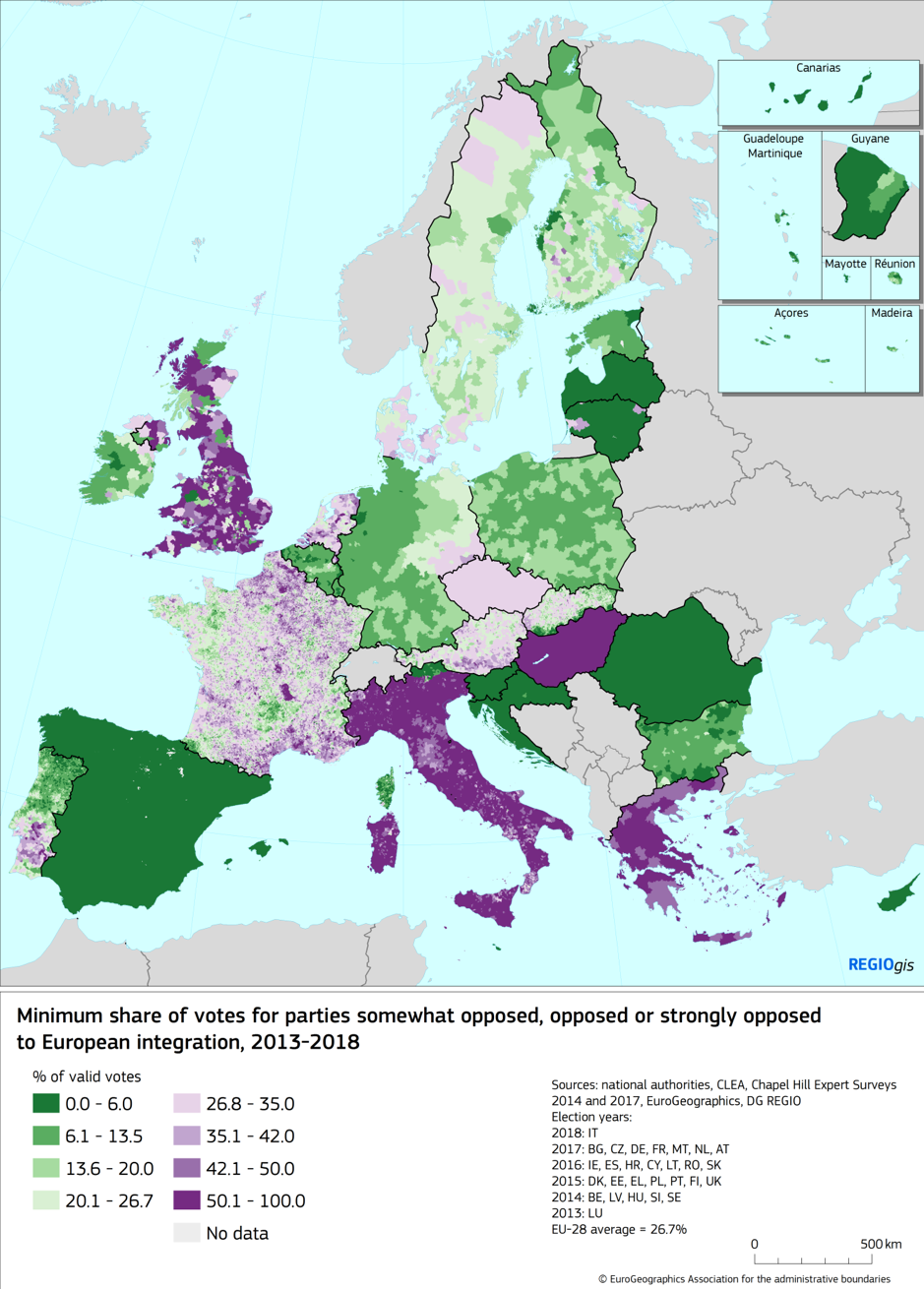

If the parties that are somewhat opposed to European integration are taken into consideration, their vote exceeded 25% of the total in ten member states. In Greece, Hungary, Italy, and the UK, the share was over 50% (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Share of vote for parties somewhat opposed, opposed, or strongly opposed to European integration, 2013-2018

What Determines the Strength of the Eurosceptic Vote?

Our maps are used to estimate, by means of econometric models, what determines the share of the Eurosceptic vote. They combine territorial factors (such as medium- to long-term economic, industrial, demographic, and employment decline) with population density or the recent migration balance, and factors linked to those considered ‘left behind’ (such as age, education, wealth, or unemployment) to explain the share of votes for parties opposed to European integration.

The maps show that while education is indeed an important factor for support or opposition to European integration, and that lack of employment opportunities also ranks high on the list of factors behind the rise of Eurosceptic vote, evidence for the dominant narrative of those ‘left behind’ ends there. One important difference with past analysis relates to wealth. Most previous research has highlighted how anti-system voters came from poor backgrounds. Yet, while local wealth matters, controlling for other factors – and especially for long-term economic decline – reveals that richer places in Europe display a greater opposition to European integration. In other words, regions with a higher GDP per head, faced with the same level of economic decline, are more likely to vote for Eurosceptic parties. This would explain the attachment of northern Italians to the Lega. Despite remaining, on average, amongst the richest citizens of the EU, 30 years of no economic growth have pushed many northern Italians towards anti-system and anti-European political options.

Moreover, the presence of an elderly population – one of the most frequent explanations for the strength of populism – does not result in a greater anti-EU vote. Once the economic trajectory, education levels, and wealth of a place are taken into account, areas with a large elderly population vote in smaller numbers for both radical and moderate anti-EU parties.

Purely geographical factors, which have attracted less attention, turn out to be robust drivers of anti-European voting. Density and rurality matter for this type of electoral behaviour, but play less of a role than that identified by US political scientists (e.g. Rodden 2016, Cramer 2017). In Europe, once moderate anti-European parties are considered, there is a reversal in the role of density: urbanites turn out to be more likely to vote anti-European than people living in less dense suburban and rural places.

However, it is long-term economic and industrial decline that emerge as two fundamental drivers of the anti-EU vote. As indicated by Gordon (2018), it has been long forecast that persistent territorial inequalities could lead to major political breakdown. But more than the gap between rich and poor regions, the long-term economic and industrial trajectory of places makes the difference for the anti-system vote. Corroborating the theory of ‘places that don’t matter’ (Rodríguez-Pose 2018), the long-term decline of areas that saw better times – often with a grander industrial past – combined with the economic stagnation of places hitting a middle-income trap, provide fertile breeding grounds for the brewing of anti-system and anti-European integration sentiments.

Overall, the vote for Eurosceptic parties in the EU is driven by specific combinations of socioeconomic and geographical factors. It is often the case that the latter shape the influence of the former at the ballot box. Hence, once long-term economic and industrial decline are addressed, it becomes difficult to assert that pro- or anti-system divides “cut across generational, educational and class lines” (Goodwin and Heath 2016). Of these three cleavages, only the educational divide remains, while the idea that age and wealth matter for anti-EU voting is much more difficult to sustain. In declining places, the old and the rich are more likely to vote pro-European. Large shares of the elderly and the poor happen to live in economically and industrially declining places, but across the whole of Europe, they are not necessarily more inimical to European integration than the rest of the population.

Hence, anti-EU voting reflects long-term economic trajectories; once they are controlled for, only education, density, and lack of employment bear out expectations.

Fixing the ‘Places That Don’t Matter’

Anti-EU voting is on the rise. Many governments and mainstream parties seem to be at a loss as to how they should react to this phenomenon. Our research offers some initial suggestions about how to address the issue. If Europe is to combat the growing geography of EU discontent, fixing the so-called ‘places that don’t matter’ is one of the best ways to start. Responding to this emerging geography of EU discontent requires addressing the territorial distress felt by places that have been left behind, and promoting policies that do not merely target, as is common, either well-developed large cities or the least developed regions. Viable development intervention designed to address long-term trajectories of low-, no-, or negative-growth regions and provide solutions for places suffering from industrial decline and brain drain is urgently needed. Moreover, policies must go beyond simple compensatory and/or appeasement measures, which will require tapping into the often overlooked economic potential of these places and providing real opportunities to tackle neglect and decline.

Place-sensitive policies (Iammarino et al. 2019) may thus be the best option for confronting the economic decline, weak human resources, and low employment opportunities that underlie the geography of EU discontent. They may also represent the best method to stem and revert the rise of anti-establishment voting, which is threatening not only European integration, but also the very economic, social, and political stability which have overseen the longest period of relative peace and prosperity the continent has witnessed in its long history.

See original post for references

I broadly agree with the argument and have made similar ones over the past two years, but I wonder whether some may think the authors biased because of their employment. Could this prove to be a problem?

Except that the correlation doesn’t work.

Take, for example, Hackney which frequently tops or is near the top of deprivation indices. But it voted nearly 80% Remain.

But then equally deprived Barking and Dagenham voted 60+% Leave, so possibly it is economic disadvantage? Oh, but then so did super-affluent Christchurch where my mother-in-law lives. But-but, maybe it’s a metropolitan influence and lower density but affluent areas are automatically Leave? No, but-but-but, even more swanky Royal Tunbridge Wells voted 55% Remain.

And so on. There is zero — absolutely none — relationship between inequality, affluence and deprivation and EU favourable/unfavourable perception. Certainly here in the U.K.

This canard was disproved three years ago, but still it gets repeated airings on VoxEU. I can only conclude that it is comforting to believe that, for euroskepticism, if the causes are solely economic then so the fix is to improve economic performance. Comfortingly, perhaps, because, it lets the EU off the responsibility hook. At least somewhat, although EU fiscal constraint Directives can hardly be inconsequential.

But if europhiles go looking for the causes of euroskepticim in all the wrong places, it will limit their chances of finding correct solutions.

What would be a far more accurate statement is that metropolitan areas are generally speaking more pro-EU and more rural, or perhaps more accurately put, less high-density population centres are more anti-EU (although even here, again, for the U.K. there are exceptions, such as Salford or Sheffield, to give a couple of examples) and so what a more useful exercise would be is to try to understand why that is.

But they state that the issue is economic growth, not absolute wealth. Northern Italy is supposedly wealthy but has been stagnant for 30 years and so is Eurosceptic.

But wealthy, modest-but-consistent growth Austria (which also has low income inequality) and so is… er… also demonstrating euroskepticism.

Low growth, stagnating Northern Ireland is europhile (56% Remain). And so on and so on.

A theory has to work consistently everywhere it is applied to, to be credible.

I think they are trying to identify a tendency, a trend, a factor to consider among many factors, not The One Reason people voted Leave. Northern Ireland has an obvious local reason to vote Remain, to avoid bloodshed. It is rather more amazing to me that there were so many votes for Leave at all. People hated the EU enough to want to restart the Troubles. (Or is thst an inaccurate reading?) Economic decline might be a factor.

But yeah, if this trend is real, it is a weak trend among a number of other trends.

I guess it’s just one view that the Brexit vote was just a clusterf__k by the Tories that gave the mopery a chance to say “bugger you” to the Establishment. Even if it was also an opportunity to shoot self in foot. An “either-or” choice in a situation where the variables were if not infinite, at leased manifold. Jimmy Carter talked about a “national malaise.” Looks like it’s more of a global malaise. Gee, I wonder why…

Much as I hate to disagree with you of all people, the “economic disadvantage predicts EU views” theory DOES hold true in some (KEY) instances. Crucially in parts of the “red wall” Corbyn must hold on Thursday. I agree the picture is, in GENERAL, much more complicated. But here in Nottingham your vote in the referendum was almost purely predictable from the IMD of your ward. (Unlike some cities, Nottm city released ward-level counts). I didn’t bother to copy and paste into Excel to plot against IMD. I’ve used the IMD extensively in my post-PhD work and I could mentally “see” that the richer the ward the higher the REMAIN vote. It looked like it would probably be a straight line….with one exception.

St Ann’s ward stuck out like a sore thumb to me for 3 minutes until I realised that it is the ward where most students from Nottm’s two universities live. So it was a nominally VERY poor ward that went REMAIN. Otherwise the relationship is almost perfectly linear. But it is a nice acknowledgement that univariable explanations are perilous (as you imply) and NOT true across the EU as a whole.

Incidentally I was curious about what the pollsters consider to be the “key seats” in the red wall for Thursday (and hence our EU future). Of 8 (ish) seats they agree on as “key”, four – Gedling, Ashfield, Sherwood and Broxtowe form the key “doughnut” around Nottm (and I live in Gedling). Gedling is predicted to stay Labour (but barely) whilst the other three are predicted to go/remain Tory. Which would explain the local canvassing behaviour I’ve witnessed round here (a Tory suburb in a Labour seat which was aggressively targeted by Momentum 2 years ago but which has reverted to being left alone by everyone – ergo a “default” Tory area). I no longer trust my gut but my gut is worried about Labour in these seats.

Any theory that anyone can come up with, even something like what colour socks you’re wearing being a marker for a Leave or Remain voter, can find some constituencies which support it.

But no theory using only a single marker or even a few combinations of some subset of markers can be substantiated across all or even most constituencies. Or, to put it another way, for every constituency which appears to validate a theory based on a single marker or a narrow set of a couple of markers, I can find another constituency which invalidates it.

A theory which cannot be reproduced or doesn’t work the same everywhere it is applied is, at best, pseudoscience.

As I mentioned, when faced with a problem — euroskepticism which is here, classified as a problem by agencies which are disadvantaged by it — it is very tempting to reach for simple explanations because simple explanations are easier to define simple remedies for. That doesn’t necessarily mean that the simple explanations are correct.

That’s kinda my point. I have no model of Euroscepticism across the EU. However I have good statistical and anecdotal evidence here across the key area of the Midlands. AND I reproduced it by correctly calling the 2017 General Election (winning after betting on a hung parliament) – I freely admit I was lucky – I ran a specialised choice model survey just before May called her surprise election so I had good national data. I made money at Ladbrokes (most of which I then lost by making a 2nd bet based on my gut, teaching me a valuable lesson). But pseudoscience? My stuff predicted even better than YouGov (and is simple extension of model that got McFadden the pseudo-Economics Nobel for predicting demand perfectly – one winner who actually deserved the prize).

I’m kinda puzzled by all the criticism – I’ve made clear how far my predictor variables go and looking at subsets of the data and predicting out of sample (as I did in 2017) is most definitely not pseudo-science – merely an acknowledgement that I my model works well for UK (non London part anyway) but I wouldn’t try to extrapolate elsewhere. Moreoever I talk to lots of people (which lots of my fellow statisticians fail to do) around here to get a better feel for my hypotheses. Sorry I seem to have rubbed you up the wrong way……

I’m just allergic to oversimplifications. And models which go all blancmange-like when presented with something a little tricky, but still crucial, like London. To say a model works perfectly, or at least tolerably, apart from London is like me saying that today I’ve had the perfect diet apart from the cake I’ve just eaten. London, because it is such a variant, is the one which really does need explaining.

OK. I’ll own up to something from my model that I never got a good handle on (i.e. I knew “what” but not exactly “why” though with more time I could know “why”). I actually got London right. OVERALL. But my survey was not powered to predict at constituency level – it was originally run as a choice model to understand “what elements of EU membership people valued most/least”. With links to political views/turnout as secondary factors (which proved crucial when a surprise election was called).

I got London correct overall. But I couldn’t claim to give robust answers to the questions you posed originally regarding individual constituencies. I have some (pretty strong) suspicions, based on my data (in terms of what people like/dislike about the EU and how it relates to their age, ethnicity, plus a load of other factors)……but I just never got round to publishing/checking that. Mainly cause the media & others never cared and I was doing the study pro bono. And now it’s out of date anyway…..

You probably got as good as it is possible to get via modelling, which isn’t to be sniffed at.

If you stumble on what to me is the absolute crux of the whole thing — why Hackney and Barking & Dagenham ended up the way they did (in terms of the referendum result) that would be absolutely fascinating. Solve that binary pair and you can probably definitely identify pro- and anti- EU determination factors.

Just a guess as it’s many years since I lived in London and never know either of those areas even then, but could it be that Dagenham is still largely traditional working class employed (or formerly employed) in big businesses (Ford etc) and beaten down by years of Thatcherism/neoliberalism while Hackney may be poor but it’s full of highly aspirational people working in tech etc. and hoping to be the next Bill Gates or fairly recent immigrants (1st or 2nd generation) for whom London is still a land of promise even if they haven’t quite found it yet.

Yes, and Susan the Other covers this point in more speculative fashion below. I think it is definitely a big part of the puzzle. One borough has still got hope. The other has lost it, if it ever had it in the first place. Or, one is optimistic, the other pessimistic. Or, one sees there being solutions and the EU might be part of those but the other sees no solutions at all, certainly none which the EU can proffer anyway.

Or some variation on that genre of themes.

Hackney’s working population feeds the City.

Dagenham was manufacturing, Ford and STC

I’m not familiar with Barking. I suspect it’s not as reliant on the City for employment as Hackney.

It may be the model needs to includes the type of industries in the area, and their future in or out of the EU,

Root causes for the views of the populace must somehow correlate to the future and stability of employment and wages growth in the area.

Measuring discontent without looking at root cause is not the best analytical research

Michael Lind has written some interesting articles about the geographic nature of populism in both the United States and Europe. I know it is the National Review but this is a good article by Lind that covers many of the issues in this post.

https://www.nationalreview.com/magazine/2016/09/26/geopolitical-cities-politics-countries/

I think the dynamics of anti-EU voting are even more dynamic and complex than suggested in this article. In Spain anti-EU voting has gained numbers in 2019 so these don’t appear in those maps. There is a distinct geographic distribution compared with, for instance, Italy. Most of them allocate in rural Andalucía in regions with many migrants (Almeria or Huelva vegetable production areas) and are more xenophobe than antieuropean. Madrid is surrounded by a belt of rural and semi-rural municipalities in which anti EU/ antimigrant votes are a majority. The narrative of forgotten regions may apply.

One of the first measures of the new comission has been to cut cohesion funds, not precisely what this article would recommend. Everything goes according to plan (If I can borrow the phrase).

I agree and you put succinctly what I thought of saying but couldn’t frame my statement effectively so had to not address this point.

EU membership, or not, is a composite question for a voter. It is made up of a matrix of factors and each voter will apportion a different weighting to the various facets. These include, in no particular order — and with some inevitable omissions:

For the U.K. Remain largely concentrated on only one component of this complex, intertwined and overlapping matrix: Economic interests. This, to me, is why it failed to move a dial which had been progressive tweaked over decades on the other aspects towards leaving the EU.

And for the EU, to attempt to implement some of the most profound social and economic changes ever effected on established societies — and then to just say to the Member States “that’s it, that’s how it is, it’s like that and that’s the way it is, so you’ll just have to jolly well get on with it” — without some repercussions seems extraordinary. The Commission’s only response, if indeed there is even one, is a knee-jerk lament that it “lacks the power” to be more effective in managing the transition and to, Pavlov’s Dog-like, request yet more Competencies be bestowed on it. Yet it is apparently stunned that there’s a tad of skepticism about the merits of this. They really could do with getting out a bit more.

a personal opinion only,

speaking from a country in central Europe: I think, the main driver of discontent transforming into anti-EU sentiment is a very common and individual experience, namely the creeping feeling of insecurity – which reaches all aspects of life, over a life span as well as day by day.

Factors like the way of reporting of crime or immigration may contibute to it, but at the center is the growing realiszation of economic decline for the many, irrespectiv of level of education and position.

Four sectors of everyday security that had long been connected to public utitities in East and in West, had been the services of public transportation, public postal services, public halth care and public media. They had not only in the past guaranteed the full spectrum of service across the whole area of the country, but also a predictable amount of low-, medium- and high-paying jobs across the whole country, from no-education labor up to to academic education. Of course, payed for by taxes, off the public purse.

All this has long gone, since at least 40 years and what poses as ersatz public services today is a crapified version in every dimenson, including the freedom of having to work 3 jobs simultaniously to survive.

So, the everyday experience of decline and insecurity is very real for most everywhere and the sentiment, to want to stick it to “them” is understandably ubiquitous.

But, as Warren Oates asked, “who the hell is they”?

Yes, I think this captures it pretty well. Although I’d say it differently – it’s not the insecurity per se, it’s the loss of security most people fell even early 2000s.

As for “Them”. Well, Pratchet told it best:

We’re very good at finding a Them. If it wasn’t the EU, we’d find something different.

Over the course of 50+ years, the EU has churned put 10,000 pages of acquis communautaire with profound implication on the social, economic, trade, institutional and political make-up of the Member Stares.

It is to as a minimum U.K. voters (not sure about other Member States’ voters, others with better knowledge an I will have to provide input) unconvincing to suggest that, if the population of the EU considers its sometimes parlous situation, the EU shouldn’t figure at least somewhere in an investigation of what’s caused all that.

It is, put more simply, a fully paid-up member of the “Them” club.

Not only should it not be given any sort of free pass, it now warrants the most forensic of picking over. To place it in a Them-free safe space is even more suspicious to a fair chunk of the U.K. population as it only reenforces the suggestion that it is allowed its own particular variant of special pleading.

The EU materialising, apparition-like, to effect change on the societies it influences, only then to try to vanish into the ether when some mud gets slung its way and say it’s just all the Member States’ faults, is a cheap party trick I for one wish it would ditch from its act.

The EU is not faceless “them”. There is no magic “EU” that on its own does all you describe.

Even the EU beaurocrats are not immaculately concieved out of the EU laws, but often delegated by (elected) EU governments (those higher up, the lower echelons are hired, usually for a fixed term that can be renewed only once IIRC). And quite a few of them are British (both in the higher and lower echelons).

Ultimately, the EU, as any other human institution, is what we, humans, make of it. Do you really believe that the UK politicians had no impact on the EU’s policies and implementations of them since it joined? Of course, we could say “but it was the French/Germans/whoever who pushed this!”. But how is it different from saying “But it’s London who’s pushing this on us!”? Sure, what right does have France to say how the UK rules will look like – but why does London have a say in how Glasgow should be run, when in reality you’ll probably find more differences between Glasgow and London, that London and Paris elites.

The EU is only an extension of “we get the government we deserve”. I know most people disagree with that, but IMO that’s only because they don’t really want to be “Them”. The UK decided that to solve its problems, it’d drop the EU. I do not believe it will work, as most of the people’s problems are inflicted by their own governments and societies, not the EU (if for nothing else, just because of the variety of the societies in the EU).

But ultimately, democracy is not a perpetual motion machine. I’m not sure we get out of it even what we put in, unless most people do the “put in” bit.

We can see it in the upcoming UK elections, where a large number of people will vote for a party that almost has it in their manifesto to make their life worse (see the conversation capture here https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/dec/03/anywhere-but-westminster-vox-pops-understanding-uk-political-landscape)

I’d buy an argument “we’re clearly incompetent to rule ourselves, just look. How can we do a larger entity well if we can’t get even a smaller one work?”.

But that’s not the argument I usually see. The argument I tend to see is “The large entity does not allow us to do it well, but w/o it we’d have a paradise on earth, because we’d rule ourselves!”. As if ruling ourselves on its own would make us all magically elder statesmen, wise and just.

Well said vlade. I worry that if Brexit goes ahead people will be very disappointed by the performance of ‘faceless bureaucrats’ in Whitehall as compared with that of their counterparts in Brussels.

I cannot speak for all areas but in my day and area the UK was unquestionably the most influential Member State in drawing up EU legislation. Not that UK Ministers would have admitted that.

Is that not the nub of the problem? Assuming you’re correct (and as vlade expressed in detail) — how can it be that, apparently, “U.K. ministers” (or U.K. appointed Commissioners advancing a U.K. agenda) got to do this without any transparency? Or linkage back to the voters and a mandate for the implemented policy programme?

It can’t be true both ways. Either the EU is replete with democratic accountability and clear governance line-of-sight from the voter to the enacted policies (in which case, the EU legislation could not simply appear, unbidden and unowned by any politician or political grouping given power by the U.K. electoral franchise — there could be no hiding place and no anonymously sponsored legislation hitting the acquis).

Or, there is a major democratic deficit and it is exactly as you described — U.K. politicians or other agents without a popular mandate can and do get legislation passed via the EU and no-one is any the wiser it wos them wot done it (this is, indeed, the oft-reported bête noire of the brexiteer and from what you’ve said appears to be factually correct).

But does this democratic deficit arise because of a choice to handle EU legislation a certain way? For instance, in Denmark all negotiating positions of ministers have to be approved by the parliamentary committee on EU affairs. Is there not something similar in the UK?

In the U.K. ministers are accountable to the U.K. Parliament so the same applies to negotiating positions here, too.

But this isn’t the same as drafting the legislation — the drafting process, which is what’s in issue here, happens after the Council negotiations have concluded and set the policy direction. The Devil, as is often said, is in the detail. The Directives are the detail.

And while I’m very pleased that for Denmark, ministerial positions have to be approved (and U.K. Parliamentary scrutiny is a similar check), what proof do you — or I — have that what is said will be done was, in reality, done? Council secrecy is a running sore, even for ardent pro-EU supporters https://www.investigate-europe.eu/legislation-in-the-black-box-of-the-eu-council-where-secrecy-feeds-mistrust/

“something must be done” is the repeated call. Yet nothing ever is.

As noted in the link, this opacity doesn’t do the EU any favours either — Member States get to hide their legislative garbage barges in EU law. The EU gets the flack. And yet, still the problem persists. I can only conclude the EU happily tolerates this, swapping bad press, which it has no difficulties in riding out, for the power it accrues.

The poor old hapless, helpless Commission, stuck because those meanie Member States won’t let it do anything. The dumbstruck Member States, lamenting a lack of EU transparency but hamstrung by EU law and those pesky treaties. Each can point the finger at the other, indefinitely. A perfect recipe for permanent gridlock. It’s almost like someone invented it to work that way…

The UK is in the EU, just about.

An inflexible ideology turned into a joke.

Free markets, free trade and EU membership will bring us all prosperity.

Did you mean ten years of austerity?

Neoliberals are so funny.

The poor things are trapped due to the inflexible nature of their ideology.

How did it work in the good old days?

“”historically the German D-Mark had been strengthening since its introduction in 1948 against the currencies of its neighbours, and this reflected – and compensated for – increased German competitiveness. Their weakening currencies allowed German trade partners to keep their export industries in business and their workers employed.” Professor Werner

This is the problem; the German economy is so strong compared to everyone else’s.

They used to have a solution; everyone else devalues their currency to maintain their competitiveness against Germany.

Then they introduced the Euro, which gave Germany an undervalued currency making its export led economy even stronger.

The weak economies, got overvalued currencies making life more difficult, and they could no longer devalue with respect to Germany.

The Euro does the opposite of what it needs to do.

What it needs are fiscal transfer from the strong countries to the weaker countries, but the Germans refused.

They papered over the cracks with debt and the strong countries lent money to the weak countries and many periphery nations boomed on borrowed money.

It all looks like it’s working well, but the debts are mounting up in the periphery nations and that debt will have to be paid back at some time.

2008 – Bang

The strong countries stop lending to the periphery countries.

Nations don’t have their own central banks to bail out the banks, and the banks in the strong countries have grown huge with financial liberalisation.

They try and strong arm Germany into bailing everything out, but German GDP is small compared to the banks liabilities.

The weak countries have to pay back that debt otherwise those banks in the strong countries will go under.

The Government bailouts of banks across the periphery lead to sovereign debt crises, along with the falling tax receipts after the crash.

The financial flows are now in the wrong direction as the periphery nations repay their debts to the strong nations.

What a mess.

Mark Blyth, a professor at a US Ivy League university, looks back at the data.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B6vV8_uQmxs&feature=em-subs_digest-vrecs

(The important stuff starts at 16 mins., long intro.)

Sorting this out ain’t going to be easy, and the populists start to rise as the years tick by.

A thousand yesses to this post — the Euro Zone is a straitjacket for all but the Dutch and Germans who have been busily exporting unemployment to their neighbors since at least the Hartz reforms.

If serious fiscal transfers are not implemented (and the Germans will see to it that they are not) the whole thing will eventually implode.

Since my attention was elsewhere during the building of the Eurozone I was stunned when I found out (in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis) how it was designed. I had previously just assumed that they had handled the single currency the way that, say Canada has. A large central bank and transfer payments between areas to even things out.

I suspect that rather than attempt anything that would result in material improvements for the people on the losing end of things though that the EU will focus more on punishing areas where support for integration has dropped.

” I had previously just assumed that they had handled the single currency the way that, say Canada has. A large central bank and transfer payments between areas to even things out. ”

Interesting comparison with Canada. The Canadian government does give equalization payments to poorer provinces that help to keep motivated provinces as Nova Scotia, whose economy was ruined by the creation of Canada at the end of the 19th century, and Quebec, where 40% of the population think that they should part from the Canadian outfit.

The Canadian system is centered on a financial oligarchy interested in the development of only a small part of the country, that is the southern part of lhe province of Ontario. Everywhere else, staple production is to go on forever, on the model of the fur trade of the old days. No economic diversification encouraged here, to say the least.

As Canada, the EU has one currency only and is heavily influenced by German banks, as Keith Calder points out. But the EU has to contend with former great powers such as Britain, France, Austria-Hungary, whose populations have not yet acknowledged that their status severely declined during the 20th century. How can these populations accept to be poorer regions in a Germany-dominated world?

Moreover, northern Italy and Denmark have their own grudges against Germany. And Sweden can be described as a smaller northern Germany that wants to keep its distance. And here we have about all the countries where strong votes were cast for anti-EU parties from 2013 to 2018.

EU-scepticism is much weaker in eastern Eurore, for instance Poland, Romania and the Baltic States. But these countries are afraid of their huge Russian neighbor and obviously prefer anything coming from the West.

So il is dubious that transfer payments would smooth things out completely. A credible oger is needed here. Too bad Donald Trump is not awarded this part!

This is really well covered in this book.

Stiglitz in his book ‘The Euro: How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe’ basically makes the same point. The Euro is of faulty design. It deprives the member states of mechanisms to combat recessions without giving them other tools into their hands. It’s similar to re-introducing a gold standard. It seems the people involved in its design had no expertise in how currencies work at all or were completely enthralled by neoliberal ideology. To remedy this will be difficult and won’t be possible without transfers between states which is difficult to imagine to be politically viable in the current climate. Not a good sign for the long-term viability of the Euro.

and I forgot to mention: he also thinks the Euro is at fault for delivering considerably depressed average growth rates in the EU since its inception since its framework is too restrictive, e. g. the ECB is only tasked with controlling inflation but not with maintaining full employment, etc., which dovetails with the mentioned depressed economic development in wide areas of the EU zone.

From my point of view the situation gets even more complicated if we think that EU and euro are,as political issues, largely but not completely superimposables in themselves, and while analyzing political trends .

Moreover, while the remarks of the authors about Italy, her local characteristics and her two “antiEU” parties are correct in bulk, they hide important details. For instance, M5s dropped any kind of real critic of the euro, whose main delivery had been the demented idea to propose a national referendum about the euro.

The Lega is a patchwork of interests and attitudes .If we observe Lega constituencies, the historical electoral strongholds of the north are under the opposite influence of the segments of productive system integrated in the German supply-chain, on one side,who are relatively happy about the EU/euro status -quo, and on the other side the segments of working-class and small enterprises etc who were hit by the crisis and stagnation, and are more sensible to anti EU and euro rants.

If we observe inside the party, the powerful Lega governors and the main apparat collaborators of Salvini are pro status-quo and pro -EU/euro, while the two main anti-euro personalities are “rented” people : Borghi , a former Deutsche Bank and Merryll Lynch manager, and Bagnai, an antieuro leftist keynesian economist who for ambition and/or desperation turned right and was elected as a senator for Lega in the South. Both were decisive in suggesting the recent attack by Salvini against the proposal of Esm reform whose approval is in agenda .

Grazie tanto, Lou Strong. My impressions in staring at the two maps are in line with yours.

First, the map doesn’t indicate which Italian parties are “euroskeptics.” The M5S is skeptical of parts of the (bad) arrangement that Italy finds itself in–I will give them some credit for fairly good judgment. The Lega, though, doesn’t get 50 percent of the vote in the empurpled regions of the North. And the authors write something like “And those little dots are Milano and Torino,” failing to note that those complicated little patches have some 6 million people. Hmm. That’s a tenth of all Italians.

On the other hand, the band of purple in the Northeast reminded me of (to paraphrase Thomas Frank), “What’s the matter with the Veneto?” You have a region that is rumored to be Italy’s richest devolving (especially the area around Verona) into some of nastiest, most vulgar rightwing expressions in the country.

And the Veneto has many local characteristics, as you write: Rich cities. Much industry, some in crisis. An enormous tourist economy. A large lingustic minority of some 1 million speakers of Furlan. And so forth. Yet the Veneto managed to elect people who are vaccination skeptics and climate-change deniers (witness the famous photo of the recently flooded city council chambers of Venexia).

Further, and the maps don’t reflect this: Many Southern Italians are skeptical of the EU because EU policies have hollowed out the South, which is now in severe demographic decline.

Thank you for your insigths on Italy Lou.

Perhaps they should look at correlations between areas most subjected to ethnic engineering and euroskepticism. It’s the new third rail. Also other factors seem to pop up when you look at the map. Anti-Russian chauvinism. (Someone once suggested back in the 90s that it made perfect sense on many levels to bring Russia into the EU. But guess who needed an enemy in case “global terrorism” failed to ignite sufficient fear to centralize authority and cement our entrenched misleadership class (h/t Ben Dixon)? Just some things to consider.

Of the 8 parties in Swedish parliament (the same 8 hold all the Swedish seats in EU parliament), none of them could rightly be classified as “radical anti-European”. The two parties which were until somewhat recently could be called anti-EU (the left party and Swedish Democrats on the right) don’t include that as part of their rhetoric anymore. Pretty much all parties except the liberals make a point of stressing that they want limitations on EU authority (even the Greens oppose giving the EU taxation power) but there isn’t much of an appetite for “Swexit” talk.

The right-wing party is largely fueled by anti-immigration sentiment, but it is mostly targeted at immigrants from the Middle East or Horn of Africa rather than Europeans.

Except there is no such thing as “post-industrial.”

Industries are still fired up and running all over the world. Everything around you is manufactured somewhere often with alot of pain and oppression on someone. But saying “post-industrial” can kind of start to put that out of the forefront of the mind, right?

I think the reference “post” means industrialism can no longer grow like a weed. There are limits to resources and energy; there is climate change and social inequality. But expanding the industrial base to meet the needs of society is now out of the question. There will always be manufacturing but it will be a different animal in future.

My guess is that they are describing self confidence. Confidence in self sufficiency. Whether locally, remote and urban, or in a crowded inner-city. Anxiety over being left behind is contagious. If circumstances are always going south, it’s not hard to understand the way Europeans are reacting to the EU. So neglect seems to be a good description of the problem. The solution is the bear. If all localities were handled equally and there was still euroskepticism then it would be safe to say that the EU is a failed experiment. It can’t provide social equality. But it is fair to say that global warming has made social equality a difficult goal under deindustrialization. It does not surprise me in the least that a million people demonstrated yesterday in France. Half a million in Paris. Because things are getting relentlessly worse. What does surprise me a little is that they were adamantly objecting to a new universal pension fund, the description of which sounded equitable. Macron is such an elitist little control freak nobody trusts him. It has already reached a breaking point. So one thing to look at, regarding all of euroskepticism, is the self sufficiency of people to maintain a decent lifestyle amidst all this change. Tapping into the human instinct for self-sufficiency and security is a good thing to do (but Macron is so despised his pension plan doesn’t sell…). My observation is that self sufficiency requires opportunity. Providing that opportunity in agreement with changes required for adjusting to climate change should be the stated goal. And it will be a massive effort.

Discontent is the key word employed, and many genuine Europeans have reason to be discontent. When the governments of individual EU countries* and the greater EU establishment at the end of the 20th century embraced neo-liberal-libertarian economics as the blue print for European integration, the project started to sour for many regular folk. The EU became less about integration and more about accumulation and concentration of wealth by the neo-liberal elites, whether they be in Berlin, Budapest, Dublin or Turin. I suspect that the EU governmental infrastructure, now thoroughly infiltrated by neo-liberal-libertarian ideology, will not be quick to change course in the near term.

Long term is another kettle of fish. I’d suggest many European minds will be concentrated in the very near future, that is if nature doesn’t take center stage first.

If I were to draw parallels, I would suggest that much of the EU geographical dissatisfaction mirrors that which folk from the United States “fly-over” country also exhibit, although the dissatisfaction can be found in many poorer neighborhoods in any city also. It is the dissatisfaction of poor wages and shitty jobs; incessant charges and fees imposed on every possible human activity by gross financialisation of every facet of human activity; and a polity antagonistic to common human decency. Our politician are shills for big money – that is their only constituency.

But many Europeans have also stopped and considered what an alternative future might look like in the light of the never-ending Brexit saga. Do we follow England and splinter the EU? What happens then? Forty years ago it was recognised that single, middle sized European countries had diminishing clout in relation to the super-powers. Has that really changed or do we all become complete vassals to a super-power?

On another note, I’ve often pondered on resurgent English nationalism as a nexus and driving force of Brexit ideology. Why has the EU has been such a provocation to that ideology and identity? After all, England had imported a veritable smorgasbord of nationalities from their old empire since the 1950s – the Caribbean and the Indian Subcontinent to mention a couple. Yet, Eastern Europeans, and Europeans more generally, are somehow considered a threat. Is it that Brexiter ideology somehow felt comfortable as top-dog and in control of the agenda as long as they dictated terms on immigration, but felt threatened when an “open” Europe allowed all its peoples to travel and work in England and elsewhere? They “lost” control and top-dog status? Might explain the fantasies of renewed empire and renewed domination of their neighbors – surmise,surmise, surmise.

On yet another note, I do know that the EU distributes regional funding for disadvantaged areas within the EU. In fact, many place in the North of England and areas in Scotland and Wales will face quite severe funding losses when the UK leaves the EU. I’m sure the EU neo-liberal-libertarian economic agenda has hurt the entire EU economy, but not as much as individual countries within the EU who’ve enacted policies that have allowed the financialised elite, via share-holder value and other such wheezes, to suck the life blood out of the regions outside major financial cities. But to suggest that specific EU legislative policies have targeted and hollowed out regional economies just doesn’t stand to scrutiny. Whereas, the transfer of wealth via trade and finance from export countries in the North of Europe to Southern regions rings very true. The Euro is not up to the job like the US Dollar is, and that is also by design.

It seems like Europe isn’t in favour of further integration but still needs deep structural realignment. If Europeans don’t make their own decisions, others will be more than willing to do so.

*often aided and abetted by so-called socialist/social democratic parties like the German SPD or the UK Labour party under Blair

The “top-dog status” as mentioned is bit of a misnomer me thinks.

The correct description would have been “disenfranchised owners”. Disenfranchised owners, who were by law prevented, in their own country, to decide whom to allow to live among them and whom not.

The combined EU and UK laws made the incoming EU populus, feel perfectly entitled to come at will and help themselves to some of someone else’s land, environment and all other trappings of a better organised and more lawful country.

English have not been reacting to rabid Scottish nationalism for the last 20-30 years. They seem to have reacted to every Tom Dick and Harry (or linguistic equivalents of), elbowing their way in and claiming possession.

Yes, a very profound question: why England (and, to an extent the principality of Wales)? It’s true that a lot of other EU Member States flirt, on and off, with euroskepticism. But it’s never really taken off in the same way as it did in England. Turning to Susan the Other’s comment above, there was a lot of neglect (a very good word to describe it) in society.

But English euroskepticism really took off in 1999, then doubled its share of the vote in 2004, added a further ten percent share of the vote in 2009, increased again in 2015 and the rest is history.

That long drawn out trajectory predates austerity and survives several boom periods including a decade long period of continuous economic expansion. Austerity, as an explanation for English euroskepticism, simply does not wash. It was simply not tenable for the traditional parties to be subjected to that onslaught of policy demand and not do something to respond to it.

But still, why England? I wish those with time and resources like VoxEU would take a proper look at it with an open mind. Perhaps, though, like me, they sense possibilities of the underlying reason and react, unlike me, by feeling threatened by the potential implications. What could one possibility be?

Perhaps it is because England has a long history of enacting profound and far-reaching social reform over many centuries in a reasonably cohesive and non-violent way. England has never needed prompting or exogenous forces to shift society’s focus and direction to address the challenges — as the cultures of the day perceived them to be — they faced and the appropriate changes (as they seemed to be at the time). Who, or perhaps what, then, is the EU to come along and — often high-handedly and with a whiff of intellectual snobbery and superiority about it, too — start telling England what’s good for it?

It’s hardly as if Italy or Greece are particularly shining examples of economic success, the Ukraine expedition a great example of geopolitical terraforming nor France’s attempts at thought-leadership entirely convincing. Bad though the U.K.’s politics and governance often are, the EU Commission’s and other EU Member States are scarcely any better. Put another way, the social, economic and cultural transformation which occurred in the U.K. between 1918 and 1968 compared with what’s become of us since between 1974 and, say, 2014 (only ten years less) makes the latter seem utterly dismal. Even if EU membership hasn’t hindered, it certainly hasn’t helped, either. If it’s neither use nor ornament, what is the point of it?

If other Member States get something out of it, then I don’t think there’s any, or there’s relatively few, in the U.K. that wish the EU ill. But there is a floating sense of unease in a chunk of the U.K. that goes back as far as I can recall that, as a concept, we’re happier managing our own affairs unimpeded. That doesn’t of course mean they will be managing them any better!

One very important consideration in the UK has been the role of the newspaper industry in England and Wales. Murdoch turned against the EU when Thatcher was deposed, partly as a result of her opposition to the deal done between France and Germany to agree monetary union as part of a package agreeing German reunification. Murdoch resented the loss of power for himself personally – he was so close to Mrs T that people wondered who was really running the UK. Major never allowed Murdoch the same influence in his government’s policies. Murdoch worked relentlessly to take the UK out of the EU from that time onwards.

Pretty much at the same time Johnson started writing his fabrications about Brussels. I am unsure quite why Hastings allowed him to remain in post. I suspect Conrad Black liked what Johnson was doing. Certainly it turned the Telegraph readers I know into Eurosceptics. Sadly too many people still trust their newspapers to tell them the truth.

One consideration may have been that Major considered seeking EU legislation to cut down the power of the press barons.

If UK newspapers had been objective in their reporting of EU matters and the UK’s relationship with the EU, the UK public would never have voted to leave the EU. Propaganda over a 25 -30 year period works.

Sorry if this is duplicative, I haven’t read the comments yet:

“However, it is long-term economic and industrial decline that emerge as two fundamental drivers of the anti-EU vote.”

So is it as simple as “We tried it and it didn’t work – at least for us?” Which it wasn’t even intended to, despite the propaganda. IOW, a straight-out response to the effects of neoliberalism.

Summer

December 7, 2019 at 1:34 pm

made a similar point about Brexit, under Links.

The graph in the article indicates that the anti-EU vote is increasing pretty rapidly, aside from a small drop in the last election. If the trend continues, the EU won’t last much longer. If I understand the discussions here over Exiting, it’s very hard for just one, as we’ve seen; but quite a different matter if a whole group of countries decide to. A glance at their maps tells you which ones. It would take time and effort, just as getting in did; and the likeliest result would be a step back to the Common Market level.

A footnote: my personal feeling was that trying to integrate Europe was a mistake, that they had it right at the Common Market level. The reason has to do with size: smaller countries are much easier to administer. At one point I made a personal list of well-managed countries. Most were European because I was using European standards – but Singapore qualifies. All were relatively small – Europe has a lot of small countries, another reason. The EU would be impossible to administer. The neoliberal infestation crippled them from the start, but I think there were bigger problems.

No, It’s not that profound. Not profound at all. Very basic really.

The surmise is simply that when England ruled an empire (or had just recently done so) they could stomach importing “colonials”, as England had control and the status of importers. Those who control are top-dog. Self esteem is provided and preserved. It’s a very basic human condition upon which all of us have acquaintance, and probably most of us practice is some small way unbeknowst to ourselves.

If the basic Brexiter belief is that Europe and Europeans are somehow inimical to English well being and identity, so be it. As far as perceived English Euroscepticism, and all that, as with most Europeans, it really don’t register anymore. It’s become…well…off radar…just…heyho, what’s new

Adieu. So be it.

As far as not having ill will to its neighbors? From your lips to God’s ears. Maybe the future will be different from history.

We’ll shall certainly see. It’s not exactly like England currently has a good track record of keeping to its agreements and commitments.

I don’t think it’s unfair to say that, after nearly 45 years, the U.K. hasn’t tried to make a go of EU membership. Maybe not perfectly. There’s certainly been some differences in approach and the advancement of specific agendas. But then, isn’t that the “say” we’re supposed to be allowed to have?

But there’s always a pervading sense that it’s never quite good enough. That we’re a bit of a downer, spoiling it, somehow, for everyone else. This is exemplified by your last two paragraphs. They certainly sound heartfelt. If unsubstantiated. If you always disliked (or are distrustful, or whatever you’d describe your views as being, I don’t want to put words into your mouth) the English surely then you’re better off without the English there, being our customary nuisances?

Or is there something else going on here?

“makedoanmend” is Irish, are they not? Lots of history there. PK’s attitude is different, but then sounds like they worked in England a lot.

My intent was not to injure sentiments. Mea culpa. I thought my statements perfectly plain and not particularly heartfelt in any specific manner. History stands for itself (open to interpretation and nuance) but well documented and substantiated unto itself.

As for UK membership in the EU. It really seems like fair weather friends territory since 2016. The UK provided many good people to the EU project (in fact, some want to stay if they can from what I’ve read) and influenced the project in many ways. But to say that the UK establishment gave the EU a good-old-try but found it unsatisfactory is over egging the pudding. You’ve got to wonder, with highsight, why they even bothered in the first place. Pragmatism, opportunism, easy moneys, all the above, none?

However, I really don’t see either the EU or England as victims in this. It a fair and square divorce. The UK’s leaving. It’s all water under the bridge now. Life finds a new balance for a while and returns to normal routines.

As for the question you pose. Given no subject matter attached nor some sort of premise with which to ponder, I can’t possibly answer.

Was it a question that is meant to be posed but not really supposed to be answered?

No, it was one of my rhetorical questions!

As you say, rightly, with hindsight, why they bothered in the first place is a complete mystery. I wish I knew whether it was pragmatism, opportunism, easy money or all three. If I had I time machine, I’d go back and ask the people concerned because it was, like you point out, with the ability to see now how it all worked out (or not…), a decision that has caused much unhappiness for both the U.K. and the EU.

Neither really deserved to be lumbered with the other given the mutual miscomprehension and basic incompatibility.

You are assuming here that the UK establishment of 1960 was the same as the establishment of 2015. They were of course completely different generations with very different experiences and world views. To my mind (and I met some of them) the 1960 generation were much more serious people probably because they had fought in WW2.

A crucial change IMO is the change in attitude of the English newspapers touched on in my post above, This of course was in significant degree a result of a change in ownership.

2 reasons visible from here: it was good for the financial industry and a lot of exporters; and, it finessed the Irish border, previously (and again) a source of intractable conflict.

The UK joined the EU pre-neoliberalism.

Is the discontent actually with the EU itself, or with the neo-liberalism the EU promotes?

The US has similar sentiments, concealed beneath a loud and noisy propaganda about how the US is exceptional.

We are seeing similar reactions to this in other countries, where the movements are suppressed by those favoring aspects of the proponents of the Monroe doctrine.