Yves here. When citizens have trouble paying for basic needs like housing, it should come as no surprise that they get unhappy and correctly blame the people in charge. But even worse, look at the spending impact. The Conservative policy largely failed even by its own warped standards. However, one might argue vote suppression of low-income households was a feature, not a bug.

By Thiemo Fetzer, Associate Professor of Economics, University of Warwick, Srinjoy Sen, PhD student, Warwick University, and Pedro Souza, Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Warwick University. Originally published at VoxEU

Homelessness and precarious living conditions are on the rise across much of the Western world. This column examines the impact of a shock to the affordability of rent in the private sector in the UK, in the form of a cut in housing subsidies for low-income households, on homelessness and insecure living conditions as well as on democratic participation. The findings suggest that the cut was, to a large extent, a false economy. The net fiscal savings for the central government were markedly offset by significantly higher local government spending to meet statutory obligations for prevention of homelessness. The cut also led to widespread distress among benefit claimants, some of whom went into rent arrears and were forcefully displaced from their homes.

A predominant issue facing the UK, and many other advanced economies, is a lack of affordable housing. With an overall inelastic housing supply and flatlining productivity growth, house prices have accelerated at a faster rate than incomes, worsening affordability. In the UK, the share of homebuyers with a mortgage declined from 37% in 2007 to 28% in 2017. This has allowed the private rented sector to thrive. The decline in new homebuyers has been nearly fully offset by a steady rise in the share of households renting from the private sector, which increased from 13% of households in 2007 to around 20% in 2017.

Housing costs, especially for the lowest income groups, constitute a significant percentage of disposable income, and many OECD countries have social assistance schemes in place to help low-income households with the cost of renting. In the UK, housing benefit provides a means-tested support for low-income households to meet the cost of rented accommodation. The fiscal burden of this welfare benefit – which is mostly a transfer from taxpayers to property owners – is growing and accounted for £21.9 billion in public spending in 2017-18. What happens if such a benefit is suddenly and drastically lowered?

In a new paper (Fetzer et al. 2019), we carefully trace out the fiscal, social, and economic implications of a drastic and persistent cut to housing benefit in the UK which was initiated by the Conservative-led coalition government in April 2011.

The Fiscal Shadow of Housing Benefit in the Private Rented Sector

The Local Housing Allowance (LHA) was introduced in 2008 as a way to compute housing benefit. The aim was for housing benefit to be generous enough to ensure that private sector tenants would be able to afford the median level of rent for a property of specified size in a local housing market (formally, within defined broad rental market areas, or BRMAs). Naturally, linking housing benefits to local rents through the LHA implied that the increase in private sector rents had a direct impact on public spending. From April 2011, the allowance for different sized properties within a BRMA was cut so that instead of covering the median rent, it only covered the 30th percentile. In addition, ‘excess payments’ – whereby housing benefit claimants who had previously lived in slightly cheaper accommodation were allowed to keep the difference in the rent and the LHA applicable, up to a difference of £15 pounds per week – were immediately cut. The cuts implied a significant financial loss for existing housing benefit claimants.

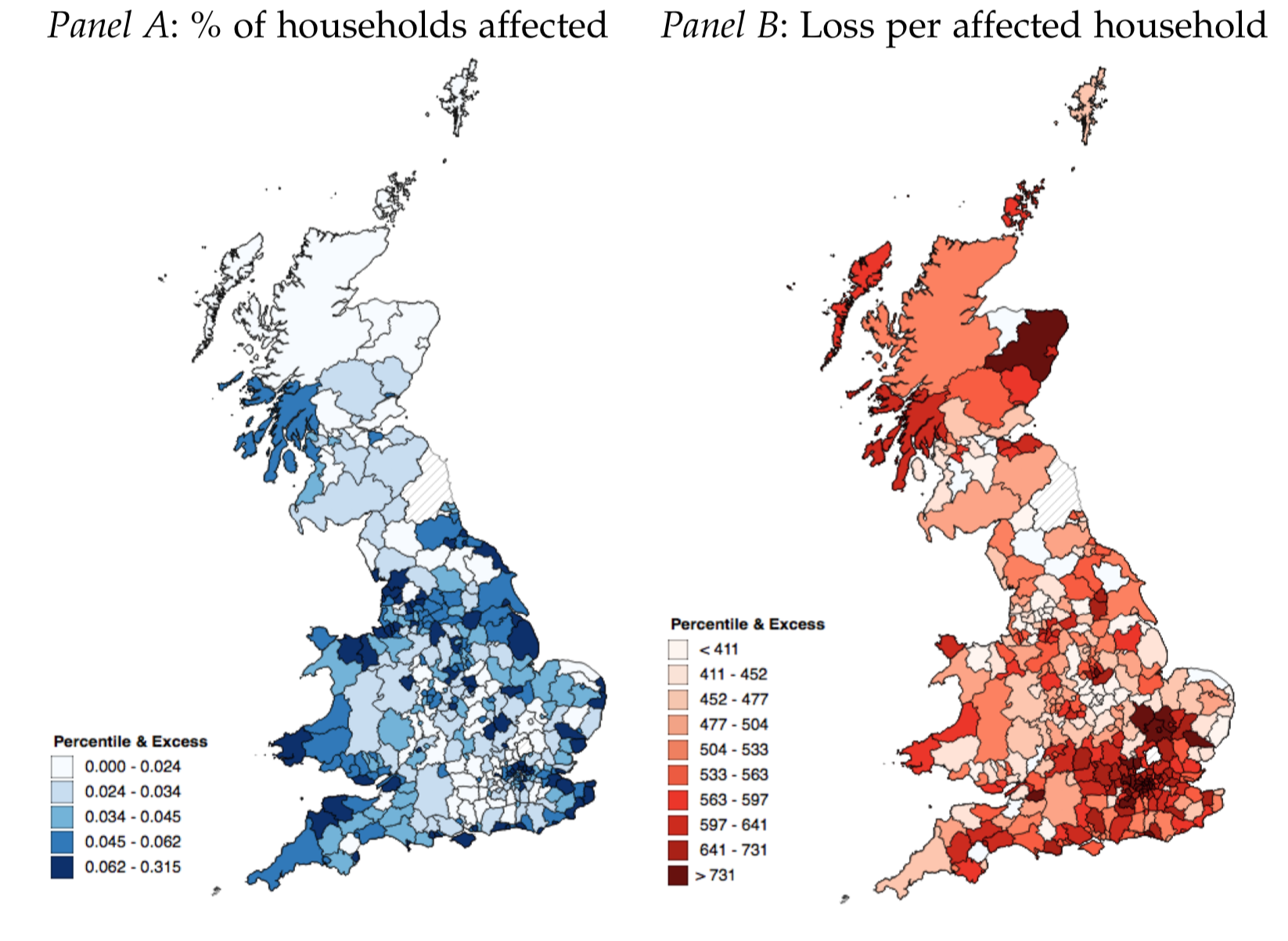

In late 2010, the Department for Works and Pension (DWP) conducted an economic impact assessment of the housing benefit cut using detailed administrative data. Panel A of Figure 1 presents data on the number of households affected expressed as a share of all resident households, while Panel B presents the spatial distribution of the average annual loss per affected household at the district level as observed from the DWP’s impact assessment of the LHA cut. The map highlights that there is significant variation across the UK in the intensity of the cut, with London clearly standing out as being among the worst affected areas. The average exposure to the cut amounted to an annual housing benefit reduction equivalent to £600 per affected household per year, rising to significantly more than £2,000 in many parts of London. Throughout the UK, around 0.9 million households in the private rented sector were affected by the cut – constituting around 5% of all households and up to 25% of all households in the private rented sector.

Figure 1 Ex-ante estimated impact of LHA cut from median to 30th percentile and the removal of the excess

We use these simultaneously introduced cuts to housing benefit to carefully trace out the fiscal, social, and economic impact of cuts to housing assistance. We mostly rely on extensive administrative data, leveraging these ex-ante projections to measure treatment intensity, and study the causal effects of the shock in a differences-in-differences framework with quite relaxed identifying assumptions.

Effect on Evictions, Temporary Accommodation, and Homelessness

We find that a one standard deviation policy shock (a loss of approximately £546 per year per affected household) in private rented sectors led to a 22.1% increase in eviction actions on private sector tenants compared to the pre-reform period, with the numbers being higher in London. There is no discernible impact on eviction actions issued to the social rented sector, which acts as a good placebo test as housing benefit for these tenants was unaffected by the reform. This finding therefore reaffirms that the impact was only observed in the private rented sector, where evictions and repossession actions were carried out, mostly due to rent arrears, as a result of housing benefit claimants in this sector being directly affected by the LHA cuts.

Households are considered to be in ‘statutory homelessness’ if the local authority considers that they do not have a right to occupy a property, or are at imminent risk of becoming homeless. Local councils have a statutory obligation to provide accommodation to these vulnerable households, which also often have a priority need. As a result of the sharp rise in evictions, we would expect an increase in demand for temporary accommodation which needs to be satisfied by the local councils who bear this statutory obligation. This is also reaffirmed in the data, with a one standard deviation policy shock leading to an increase in statutory homelessness and rough sleeping rates of between 10-13% and nearly 50%, respectively, along with a rise in households being placed in temporary accommodation of 18.8%.

Data provided by councils provide further evidence on who is affected by homelessness and why they became homeless. Since 2011, the structure of statutory homelessness has dramatically shifted, with rapid rises in homelessness concentrated in the working-age adult population and, in particular, among households with children. A one standard deviation increase in exposure to the housing benefit shock is associated with a 25% increase in the number of families with children being classified as homeless. The predominant reason why households become homeless in districts most exposed to the housing benefit cut is (legal) eviction from rented accommodation.

Individual-Level Evidence

Naturally, studying households in precarious living conditions using survey data is difficult, as these households may be particularly likely to move frequently from one accommodation to another, which may increase the risk that they drop out from such panel surveys. In the Understanding Society Panel Study, we find that between 40% and 50% of private rented sector tenants drop out from the panel study. For individuals that own their property (outright or with a mortgage), attrition rates are much lower at around 30%. Using the Understanding Society Panel Study, we highlight that attrition is likely an important margin: we find that individuals (likely) exposed to the housing benefit cut were much more likely to drop out from the panel study after the reform took effect. We further show that it is these same individuals who are exposed to the benefit cut that report that they are increasingly falling into rent arrears rent in the most recent wave prior to them dropping out from the survey. This highlights that survey data, which are often used to inform policymaking, may be systematically skewed and not representative of vulnerable sample populations if there is policy-induced selective attrition.

For a small subsample of households that do not drop out from the survey, we further observe that individual-level exposure to housing benefit cuts is associated not only with increased rent arrears but also with a higher propensity to be evicted, mapping very closely to the results obtained from the district-level analysis.

Effect on Electoral Registration and the EU Referendum Vote

We also link exposure to the housing benefit cut to measures of democratic participation. The more descriptive results suggest that a one standard deviation increase in exposure to the housing benefit cut is associated with a non-negligible reduction in the electoral registration coverage rate (i.e. the ratio between the number of registered voters in a district and the number of voting-age adults in that district). We further document that a one standard deviation policy shock is associated with a fall in the official electorate for the 2016 EU referendum as a share of the voting-age population of 0.7-0.9 percentage points. The actual turnout for the referendum was significantly lower in districts more affected by the cut, with a one standard deviation increase in exposure to housing benefit cut leading to a fall in turnout of 1.3-1.8 percentage points. Lastly, we also observe that a one standard deviation increase in the level of exposure to the cut in a district is associated with up to a 2.2 percentage point greater level of support for ‘Leave’. This effect is likely driven by the composition of the electorate, as studies since the referendum have revealed that among those that did not turn out in the referendum, support for Remain outnumbers support for Leave by 2:1.

Fiscal Neutrality

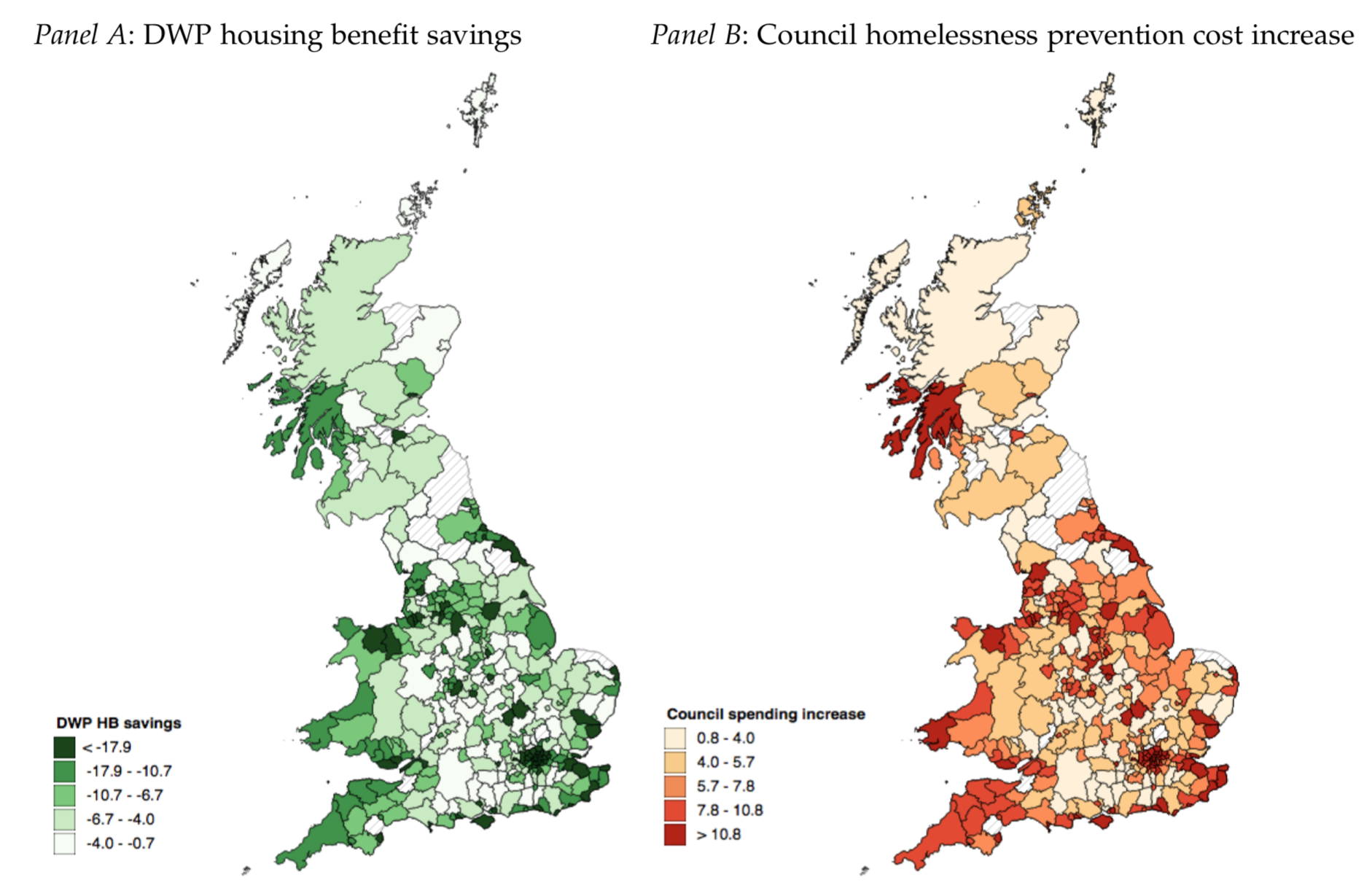

The housing benefit cut dramatically increased statutory homelessness and rough sleeping, as mentioned above. Since local authorities have a statutory obligation to house households that are, or are at risk of becoming, unintentionally homeless, the local authorities had to rent properties, sometimes from private landlords and often at market rental rates, to provide temporary accommodation and other homelessness prevention services. Even though the cut to housing benefits was originally intended to provide fiscal savings to the DWP, we show that a large portion of the savings were offset by local council spending on anti-homelessness measures, thereby leading to a dramatic shifting of the burden from central to local government. This partially defeats the original object of the housing reform, which aimed to reduce fiscal exposure to rapidly rising market rents. Figure 2 illustrates the lower housing benefit spending by DWP and higher local council spending on anti-homelessness measures.

Figure 2 Cost-benefit analysis: Implied fiscal savings to central government from housing benefit cut versus higher council spending on homelessness (pounds per resident household)

Our calculations denote that in the case of the median (mean) council, for every £1 saved in lowering spending on housing benefit, 75p (53p) is spent on preventing homelessness or on housing individuals at risk of becoming homeless in temporary accommodation. The further indirect social and economic costs due to the potential adverse effects on outcomes, especially for children brought up in insecure conditions, likely weigh in even further.

Concluding Remarks

Cutting housing subsidies, while appearing to be fiscally attractive, may result in significant economic and social costs. Insecure housing and forced displacement – which, as we show, can directly result from cuts to housing assistance – may result in further social costs such as negative consequences for health (Fowler et al. 2015) or labour markets (Van Dyk 2019), and may also have adverse effects on children’s educational attainment (Humphries et al. 2019, Chyn 2018). We also show that insecure housing may erode democratic participation, increasing concerns over political legitimacy. In that sense, our work contributes to a growing literature that examines the role that housing plays in shaping contemporary political preferences (Ansell 2014, 2019, Adler and Ansell 2020), and in particular the role that welfare cuts may play in shaping political outcomes (Fetzer 2019).

See original post for references

No mention of the effect of Universal Credit but they are perhaps included in the figures above. After I ceased being a carer & had to sign up for UC, my allowance was £ 70.00 per week with an additional payment of £67.00 towards my rent of £110.00 per week. This meant that I was expected to live on £27.00 per week & thanks mainly to Sinn Fein I had no bedroom tax to pay.

Nuff said ? & as I have said before I had a credit line from a family member which I kept as low as possible, no debt to speak of, no kids, I know how to cook cheap nutritious meals, got used to wearing 5 layers of clothes through most of the Winter & have no need to buy pretty much anything besides those things that are essential to live off – 6 months of hard boot camp basically.

As for the credit part of the name you start kind of like it’s year zero & none of what went before counts for anything. All the tax & national insurance paid, the fact that you had spent your life working your bollocks off, successfully raised a family, cared for 2 sick women twice, nothing matters – you become nothing more than a useless burden to the state & should probably just follow Lambert’s law of Neoliberalism & quietly go **** off & die somewhere.

Well, **** them, I’m still here.

& should probably just follow Lambert’s law of Neoliberalism & quietly go **** off & die somewhere. Eustache de Saint Pierre

The righteous man perishes, and no man takes it to heart;

And devout men are taken away, while no one understands.

For the righteous man is taken away from evil,

He enters into peace;

They rest in their beds,

Each one who walked in his upright way. Isaiah 57:1-2

The older and more cynical I get, I am trending towards the concept of “Instant Karma.” I now have a much greater sympathy for the Anarchists gamely struggling along. As I was taken to task years ago here by another commenter, not Kropotkin style Anarchists.

not Kropotkin style Anarchists

Why not? I just heard of him but he sounds quite reasonable per wiki.

Yes, and that is exactly my point.

“Reasonable” in the context of power struggles between classes is a losing strategy for the weaker ‘actor.’ The only ‘real’ class based struggles I can see, I speak of the union movements of a century ago, had to resort to violence of various sorts to get any concessions at all from the owning and managerial classes.

It is past time to be speaking of ‘incrementalism’ and ‘reasonableness.’

I’d say the Corana-virus is all the violence needed to make the PTB wake up to the need for justice, mercy and reform (“The Lord works in mysterious ways…”).

Otherwise, you’ll create fear, harden hearts and justify ruthlessness, imo, and per the Bible as I understand it.

Thanks for the quote from the old book & I am OK, got off much much lighter than most who are stuck in that trap. The hardest part of that period was losing the woman I love who needed to get proper care elsewhere. Our 2 guinea pigs kept me going when despair occasionally set in, raising a smile when they nagged me for being late with the morning’s fresh hay.

Kicked around since my late wife’s first bout of cancer in 1997 followed by a series of large bad events that started slowly then accelerated, particularly over the last 6 years. Now working long hours while still waiting for money owed from now 8 months ago. Get myself into a much smaller place nearer to my fragile bird, which will make it easier to visit her.

I can understand why in particular people my age who have ended up on the scrap heap are angry, especially as we remember all the broken promises & see unlike the young how things have changed for the worst – I have spoken to some who are truly & very deeply in despair.

As an Irish comedian used to say as he ended one of his TV shows :

” May your God go with you “.

The root of the problem is allowing banks to capitalize on, not the value of housing, but the land value underneath. This can become a very messy subject, but in rudimentary form – public infrastructure spending creates the value of land sites to begin with so why should any private citizens gain from this? Ground rent, or land value capture, paid to the community for its services, would go a long way in bringing down the cost of housing (its inflated land price). As it is, the government, being captured by by the FIRE sector, subsidizes private land gain speculation, thereby inflating its price.

https://www.truthdig.com/articles/how-the-rentier-class-cannibalizes-the-economy/

The UK is a throwback feudal system of rents and rates. That’s why Companies get Relocation services, whereas households get Removals, as in eject the delinquent peasants.

living in council housing as a child in Birmingham UK, my mother was a transient never satisfied that the green grocer or butcher in the area we inhabited was not placing a thumb on the scale. Point is we lived in a variety of housing some private owned but close to the end of land l;ease allocation. All city land was on a 99year lease. the closer to the termination of the land lease the cheaper the house was to buy, (you cannot move a house in a row of 8-10 even if you had a plot to put it on. The house would likely either revert to the city “council house”, or be demolished for newer housing stock. few working families ever expected to own a home.

Now the financial economy is in trouble we should be planning for what comes afterwards. I, for one would entirely remove gamblers from the housing and food markets. So long as we have only one type of money for exchange, we need to get those two markets free of financial market pollution. The moneymen can continue to take wealth from dedicated followers of fashion and charge fancy prices for entertainments and sports fixtures but, in those essential supplies for the maintenance of life, they should be evicted for ever.

What you propose was precisely the reason for providing Council Housing in the UK.

Yes, but lets not forget the people of britain voted for this.

Where are the homeless from, Mexico?