Yves here. It bears repeating that the Fed is not at all keen about negative interest rates. Indeed, it wasn’t even keen about super low interest rates once it realized they had been unproductive to counter-productive but given the weak recovery, the central bank also found it hard to back out of that corner. The Fed has even gone as far as grumbling about the ECB’s unseemly willingness to engage in negative interest rates.

Needless to say, the Swedish experience (and its central bank’s abandonment of its experiment) supports the Fed’s priors.

Bear in mind that the Fed not being on board with negative policy rates does not mean Mr. Market might not shift in a panic into negative interest rate terrain for some instruments. Given the previously-unthinkalbe spectacle of negative prices for WTI contacts, coronavirus dislocations can create all sorts of anomalies.

By Fredrik Andersson, Senior Research Associate, Cornell University and Research Economist, US Census Bureau and Lars Jonung, Professor, Knut Wicksell Centre for Financial Studies, Lund University. Originally published at VoxEU

Negative interest rates were once seen as impossible outside the realm of economic theory. However, recently several central banks have imposed such rates, with prominent economists supporting this move. This column investigates the actual effects of negative interest rates, taking evidence from the Swedish experience during 2015-2019. It is evident that the policy’s effect on the inflation rate was modest, and that it contributed to increased financial vulnerabilities. The lesson from the experiment is clear: Do not do it again.

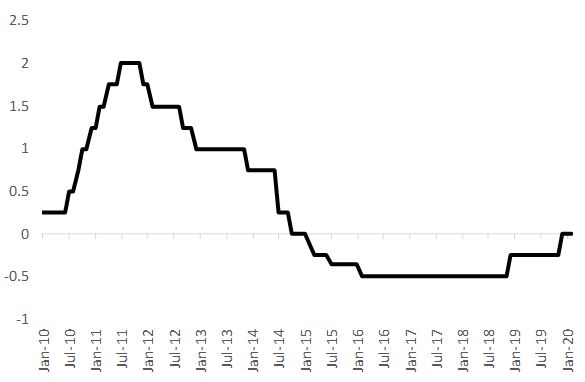

Several central banks have recently imposed negative interest rates, with prominent economists supporting this move (e.g. Bernanke 2020, Lilley and Rogoff 2019, 2020. The Swedish Riksbank was the first central bank to introduce negative rates in 2009 when it imposed a negative deposit rate for commercial bank holdings with the Riksbank until 2010. The main policy rate (the repo-rate) remained positive until February 2015 when the Riksbank then lowered it to -0.10%. It was further reduced to -0.50% in 2016, a level maintained until January 2019 (Figure 1). The negative repo-rate was finally abolished in December 2019. Among the five central banks with negative policy rates in recent years, the ECB, the Danish Nationalbank, the Swiss National Bank, and the Bank of Japan, the Riksbank was the first one to leave the negative territory.

It is too soon to make a full assessment of the long-run effects of the use of negative rates. However, we can already observe some of the short-run consequences. Here, we focus on how the negative rates have affected the Swedish economy during the period running from 2015 to 2019.

Figure 1 The Riksbank repo-rate, 2010-2020. Percent.

Background

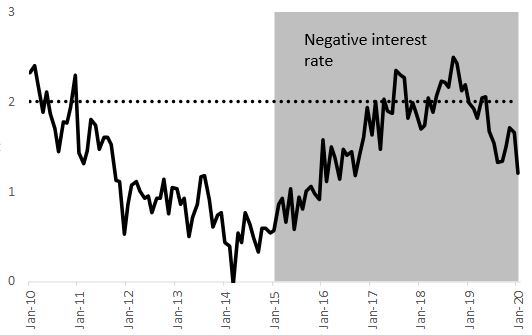

After the Global Crisis of 2008, the Swedish economy recovered rapidly in the second half of 2009. Real GDP surpassed its pre-crisis level in as soon as 2010. Inflation rose above the Riksbank’s official inflation target of 2% (Figure 2). Strong growth and higher inflation caused the Riksbank to begin to normalise its policy by gradually raising its policy-rate to 2% in 2011. However, inflation began to decline following the euro crisis and the weakening of the euro area economy. By 2014, inflation was at 0.5% (Figure 2).

As inflation declined, the Riksbank reduced its policy rate first to 0.75% (in December 2013), and then 0% in 2014. Despite a falling policy-rate, inflation did not pick up. Consequently, the Riksbank took a major step in February 2015 by introducing a negative policy rate. The negative rate was maintained until December 2019 when the Riksbank terminated this policy, at least for the time being.

The Riksbank also started to purchase government bonds in February 2015 (quantitative easing), totalling almost 300 billion SEK by 2019, a sum close to 6% of GDP. While the Riksbank may have abandoned negative policy rates, its quantitative easing programme has not yet been reversed.

The Effects of Negative Interest Rates

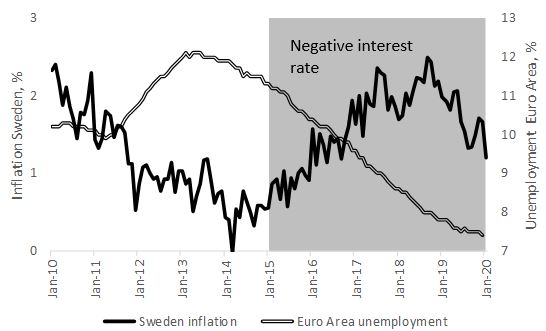

As is evident from Figure 2, domestic inflation did rise after the introduction of negative rates and reached the inflation target of 2% by 2018. Based on this outcome, it is tempting to conclude that the policy of negative rates has been a success. The aim was to bring inflation back to the target and it did succeed in doing so. However, Swedish inflation is highly correlated with the European business cycle. Figure 3 depicts Swedish inflation (measured by the Riksbank’s official price index CPIF) and the euro area unemployment rate. Swedish inflation falls when euro area unemployment increases, and vice versa. In fact, the correlation between the Swedish inflation rate and the euro area unemployment rate is -0.8. In contrast, the correlation between the Swedish inflation rate and the Swedish unemployment rate is much lower, at only -0.3.

The Swedish economy is highly integrated with the European economy. Swedish exports as share of GDP increased from 30% during the 1980s (before Sweden’s membership of the EU in 1995) to between 45% and 50% in the 2010s. The Swedish business cycle is thus of less importance than the European business cycle for how domestic inflation evolves in Sweden. As a result, improved economic conditions in the euro area are a greater factor behind the rise in inflation than the Riksbank’s expansionary policy based on negative rates.1

The rise in inflation during 2015-2020 is not unique for Sweden. In the euro area, inflation rose from -0.3% in February 2015, to 2% in the middle of 2018, and then to 1.4% in January 2020. This is almost exactly the same pattern that holds for Sweden itself, where inflation rose from 0.9% in February 2015, to 2% in the middle of 2018, and then to 1.2% in January 2020.

Figure 2 The rate of inflation in Sweden, 2010-2020. Percent.

Figure 3 The rate of inflation in Sweden and unemployment in the euro area, 2010-2020. Percent.

While we argue that the Riksbank’s negative interest rates have had, at most, a minor impact on the domestic inflation rate, we do observe major effects of this type of monetary policy on other parts of the Swedish economy, most prominently on the exchange rate, the housing market, and the level of household debt.

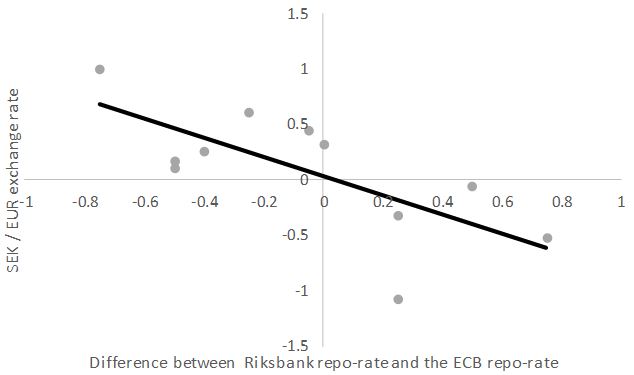

Figure 4 illustrates the change in the SEK/EUR exchange rate (number of Swedish krona per euro) in relation to the difference between the Riksbank’s repo-rate and the ECB repo-rate. During the last five years, the Riksbank has pursued a more expansionary policy than the ECB, despite a stronger Swedish economy in comparison to the euro area economy. This has reduced the value of the Swedish krona from an average exchange rate of approximately 9.25 SEK/EUR between 1999 and 2012, to a rate of 10.50 SEK/EUR presently. During the period with negative rates, the krona depreciated by 20%, from 8.50 to almost 11 krona to the euro. At the most, this depreciation contributed to an increase in the Swedish inflation rate by one percentage point. In the process, Swedish households have become poorer seen in this perspective

Figure 4 Change in the exchange rate between SEK and EUR and the difference between the Riksbank repo-rate and the ECB repo-rate, 2009-2019.

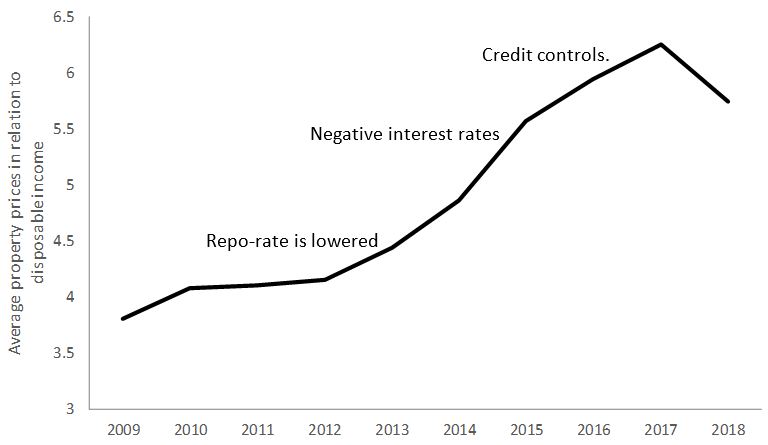

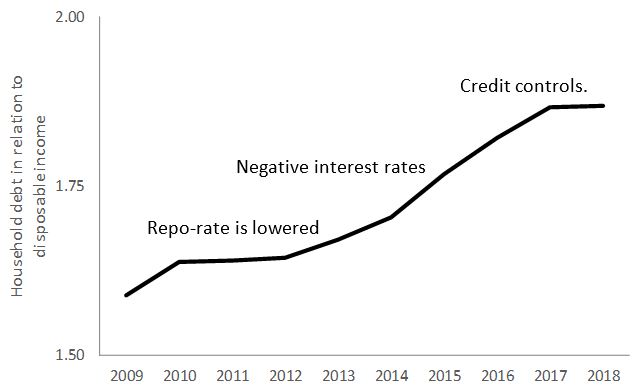

Swedish property prices and household debt levels increased rapidly prior to the Global Crisis of 2008, raising concerns of a future correction and possibly a financial crisis (Andersson and Jonung 2016). Sweden suffered briefly from the crisis of 2008, but no major bank collapsed, nor was the housing market hit during the crisis. The crisis and higher interest rates during the monetary policy of 2010-2011 stabilised house prices (Figure 5) and household debt (Figure 6), albeit at historically high levels.

The lowering of interest rates in 2012-2014 raised property prices in relation to disposable income further. They also rose following the introduction of negative rates (by close to 50% in relation to disposable income between 2012 and 2016). The financial supervisory authority (Finansinspektionen) felt compelled to take action, imposing a string of credit controls on households such as amortisation rules and debt ceilings, beginning in 2016. These controls dampened the rise in real estate prices and in debt. However, they also contributed to growing inequalities as the credit controls were mostly binding for younger households and other households without assets. Nonetheless, the credit controls have not stopped the upward trend in real estate prices.

Figure 5 Average property prices (flats) in relation to disposable income, 2009-2018.

Figure 6 Household debt in relation to disposable income, 2009-2018.

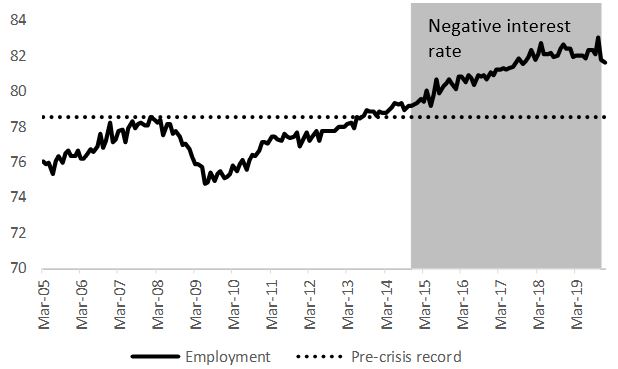

Historically, the Swedish inflation rate has been a good indicator of the business cycle. Inflation increased during booms and declined during recessions. However, the correlation between the Swedish business cycle and the Swedish inflation rate has weakened. While inflation was low in 2014, the economy was booming. Growth was close to 3% and the employment rate for 16-64 year olds hit a record level, at close to 80% (Figure 7). The employment rate was even higher than during the pre-crisis boom of 2008.2 Rather than being counter-cyclical (tightening during booms), monetary policy became clearly pro-cyclical. The Riksbank’s raising of rates in 2019 actually coincided with the economy moving towards a slowdown.

Figure 7 The rate of employment of 16-64 year olds, born in Sweden, 2005-2020. Percent.

Conclusions

The Governor of the Swedish Riksbank, Stefan Ingves, described the use of negative interest rates an “experiment” never tried before (Dagens Industri 2017). The experiment is now over, at least for the time being. We conclude at this early stage that the costs of negative interest rates to society most likely exceeded the wider benefits.

The Swedish economy is closely integrated with the European economy. Domestic inflation depends more on euro area developments than on domestic conditions. The Riksbank’s negative policy rate has not contributed to a significantly higher inflation once changes in the euro area economy are taken into account. The policy failed to reach the 2% target while creating major imbalances in the process.

While the impact of the negative rates on the domestic inflation rate is small (probably negligible), the effects of negative rates on the housing market and on household debt levels are large. Imbalances which had already begun to materialise before the Global Crisis have worsened. Real estate prices have risen rapidly, contributing to rising wealth inequality. Household debt has reached record levels. The exchange rate of the Swedish krona has depreciated by more than 10%, with no major impact on the domestic rate of inflation. In addition, monetary policy has turned pro-cyclical during this experiment with negative rates, contributing to record high employment. In short, this has created an economy with signs of ‘overheating’. However, this is likely a short-run gain. The Riksbank will face a major challenge to calibrate its policy during the next downturn.

The introduction of negative rates in 2015, coupled with a quantitative easing programme, was motivated by a rate of inflation below the official target of 2%. Although inflation was below the target, there is no evidence that the low inflation rate (at around 1%) has caused any harm on economic performance. The labour market was strong and economic growth was high. The narrow focus on the fixed inflation number of 2% forced the Riksbank into its experiment with negative rates. A more flexible approach to the inflation target, focusing on a tolerance band rather than on a fixed number, would have allowed the Riksbank to take a more nuanced view on the overall macroeconomic stability, rather than just on consumer price inflation stability (Andersson and Jonung 2017).

Of course, we do not claim that everything would have been fine with the Swedish economy if the Riksbank had avoided negative rates. Instead, we suggest that the Riksbank would have faced a better-balanced economy today, better balanced in the sense of less asset price inflation, less financial imbalances, and more room for the Riksbank to react to the next downturn.

The Riksbank law permits the Riksbank to revise the inflation target as economic conditions change. The Riksbank is not required by law to maintain 2% inflation at any cost (Proposition 1997/98:40). Still, the Riksbank chose to experiment with the Swedish economy when it did not have to do so.

Economic policies change over time as policymakers learn from past mistakes and successes. Sweden has served as a laboratory of policy experiments in the past (Jonung 2000, Andersson 2016). The Riksbank, the oldest central bank in the world, has just terminated its most recent experiment. In our opinion, the clear message from the Swedish experience of negative policy rates is: ‘don’t do it again’, at least not when the domestic economy is booming, domestic inflation is determined by foreign inflation, and the financial imbalances are rising through high asset price inflation.

See original post for references

This makes me want to draw a parallel with US housing inflation. That it is an underlying imbalance with capitalism itself. For one, in Sweden they seem to be saying that housing and domestic prices went up with NIRP because people were buying fixed assets. That makes sense and sounds like the US. But then they say that during this time Sweden benefited by having the EU to trade with which helped to stabilize the economy but kept it too close to deflation. So the inflation didn’t show up in the other half of the economy – the business half. Which also males sense because NIRP effectively reduces the value of the currency and improves trade. So bottom line is that Sweden is now having to deal with domestic inequality because many people are priced out of the housing market and domestic goods are becoming expensive. Here in the US all those things happened without going NIRP. Never mind that we had that little incident in 1971 with gold and good riddance to it. So maybe it’s apples and apples. The thing I can’t understand is this: if governments know this happens – all this inequality – why are they (the USA) so averse to using MMT to direct spend into the fiscal domestic economy as necessary. There doesn’t seem to be any other balancing act except homelessness and poverty which is totally unacceptable. I think this imbalance between currency, business, fixed assets and domestic wealth is what happens when profit is sucked out at the top and not but back in at the bottom.

put back in at the bottom

Negative Interest Rates are a bust, because the banks won’t let people borrow at -1%*

* Some exceptions in Denmark I understand.

How much money for how long at -1% ?

Answer – Well as much as I can for as long as I can. It’s free money :)

1 Billion for 1 year @ -1% = 990 million repayment => 10 million for me.

1 million for 1 year @ -1% = 990,000 repayment = 10,000 for me.

Better I’ll pre pay in advance and you can just cut me the check for the difference

Now if I could borrow it for 100 years…..

We in the US already have negative real interest rates after inflation, and have for some time. As the writer mentioned, a policy of negative nominal interest rates has failed to spur economic growth in other countries whose central banks have tried it, including Japan, the EU and Switzerland. So in the face of such failure, what is the persistent reemergence of proposals for negative nominal interest rates really about, including recently by the former president of the Minneapolis Fed? Well, in my view it’s about several things, none of which flow through to materially lowering rates on consumer debt, are broadly beneficial, or relate to the efficacy of this policy to address deflation:

1.) Supporting collateral valuations to protect the debt leverage in the system and to provide those who engage in speculative finance with political leverage to defend their structures against legal restoration of the separation of the nation’s depository and payments system from speculative finance.

2.) Elevating financial asset prices that disproportionately benefit a relatively small segment of the population, and protect the existing political, financial and legal processes which enable them to influence lawmakers. Unfortunately, besides contributing to extreme wealth inequality, this also serves to create bubbles and systemic risk.

3.) Power and class war: Essentially they are saying to savers, “We can disenfranchise you of your financial and social resources, reduce your independence, and increase our control anytime we choose to do so. Fundamentally, it’s the same underlying message that’s behind periodic initiatives for more wars, cuts to public education, defunding public infrastructure, cutting Social Security, reducing environmental and public health funding, further eroding our right to privacy, or forcing incremental state and local government debt together with attendant increases in taxation that are necessary to service such state and local debt.

The proponents of this policy evidently believe they can manage the nonlinearity and feedback loops that are emerging from the economic, public health and political effects of the coronavirus pandemic to protect themselves from loss and preserve their privileges through massive monetary subsidies to their favored constituencies. But as a recent article in FT observed, central banks may be storing up future problems in their effort to shield credit from losses.

Thanks Chauncey, great comment.

Thanks, RabidGandhi. Suspect given the ownership of selected US equities by some foreign central banks, there may also be a geopolitical component. Just a hypothesis, given the remarkable rally off the lows. But, I think it’s fair to say that nobody who owns stocks needs that money for food and shelter, unlike the predicament of many suffering from the economic fallout of the pandemic.

Peter Boockvar also posted a list of observations on Twitter yesterday about why NIRP is a very bad idea:

https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1258775486911700992.html

When are we going to ditch the neoliberal experiment ! Running two economies one for the 5% and one for the slugs who do all the productive work!

Just reading about the

rentiersinvestors in the stock market being comfortable with the increasing “value” of the stock market despite the now apparent existence of the Second Great Depression is both depressing and fascinating. Employment, business and home rentals, land, and wholesale and retails sales have collapsed and yet it is all about letting the good the times roll! After all their wealth of air is increasing.Sometimes, actually almost always, I think that the elites are determined to keep their good times rolling no matter what because they believe that they can; the more precarious their position becomes the more they cling to their delusions, which further threatens us all. They must be able to control reality because they are the masters of the universe, so it just is. Those who have been slapped by reality, which is most of us, know that this isn’t so, but the Cult of the Elites are immersed in their bubble. I’m afraid that until the collapse physically affects the masters in Congress, we are just going to increasingly suffer.

The answer to your question is Kalecki’s 1943 paper. (pdf).

Businesses know full employment is good for the economy and good for them. They’d rather have the power over employees that “labor discipline” implies. The message: “You had better take whatever crappy job is on offer, or suffer the indignities of poverty, even homelessness and starvation…and if you’re ornery, incarceration.”

Given Yves recent experience with elder care workers, one wonders whether management has a point. Or have workers become so abused they expect to stumble through their job without thinking. It’s easy to blame management for all the trouble, but unions are no innocents, too.

(This comment is disorganized, but I am using my phone and have erased it twice.)

Speaking from both experience and reading, I will say that in much of the retail world employers do not intelligence, initiative, and often not even competence. Having worked with people who had or were doing office work, at least the general experience is the same. Being something other than a drone can get you punished and rewards are rare. Wages have risen more slowly than the cost of living. You need to work several jobs often with erratic hours. And because you are poor you are never, ever caught up with the bills. Just forget about saving.

In the Bay Area the effective minimum wage is probably $15. Don’t count on getting over $18. Apartments start from $1,800. (Department of Housing and Urban Development has determined that one has make over 110,000 per year here to not be poor with regards to housing.) Being able to pay rent and basic utilities means that you make too much to qualify for SNAP.

In order to survive especially with family members to support it’s likely you will have to work 2-3 jobs and work at least fifty hours a week. It is almost impossible even with a supposedly middle class income to pay all the bills and save. For even the working class, forget the poor, it is impossible. If you have family, good luck.

So, you are working your two or three jobs at over fifty hours a week in places where everyone else is also tired, hungry, overworked (corporate must get its value from the lazy workers), and always having unpaid bills. Verbal abuse, unreasonable demands, and insane behavior is perfectly acceptable. Complaining is a firing offense.

Training aside from the fabulous first day training videos ended decades ago. It does cost them money. Your fellow employees and immediate supervisor in their copious spare time train you while you work.

If you don’t put on the Smiling Idiot Face and effectively say “thank you sir, can I have another?” you might get fired. Don’t think. Just be the abysmally paid drone that they want.

Some managers enjoy firing people and there is nothing you can do about it. They enjoy their power. Just slavishly obey. If nothing else, they will cut your hours. You have no protection. Might need another job. And gas is usually expensive and public transportation does not transport the public well.

And unions. What unions? My parents generation got those, but they have not really been a thing since they were exterminated by the 1990s. Even the remaining public sector ones seem to emasculated lapdogs.

In the Soviet Union they used to say: “they pretend to pay us, so we pretend to work.”

Out here in Caly, Newsom has run up $46 billion in debt with government workers hiding all over the state doing non-essential work, expecting a big payday for his effort.

If he doesn’t get the “customary” treatment, this is going to get ugly fast. The central banks can only ride faamg so long.

Faamg = China economics.

If govt economists continue, rates will go negative whether they like it or not. Not the brightest bulbs.

In case anyone isn’t doing the math.

Central bank independence seemed like a good idea at the time:

1) We had a new, scientific economics for globalisation that would ensure globalisations success.

2) Technocrats, free from political interference, wouldn’t make decisions swayed by politicians looking to gain votes with giveaways to the electorate.

The new, scientific economics was basically 1920s neoclassical economics with some complex maths on top.

The economics of globalisation has always had an Achilles’ heel.

In the US, the 1920s roared with debt based consumption and speculation until it all tipped over into the debt deflation of the Great Depression. No one realised the problems that were building up in the economy as they used an economics that doesn’t look at private debt, neoclassical economics.

Not considering private debt is the Achilles’ heel of neoclassical economics.

The only thing that keeps this thing running is adding more debt, and as long as interest rates keep falling you are OK.

When you hit zero, the next step is negative.

The FED does the best it can with an economics that doesn’t consider debt, which really isn’t very good at all.

Greenspan and Bernanke can’t see the problems building before 2008.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAStZJCKmbU&list=PLmtuEaMvhDZZQLxg24CAiFgZYldtoCR-R&index=6

At 18 mins.

(When you use neoclassical economics that doesn’t consider debt, the economy runs on debt and then crashes in a Minsky Moment, 1929 and 2008.)

No one can work out what caused 2008, and afterwards and they attribute it to a “black swan”.

Janet Yellen is not going to be looking at that debt overhang after 2008 and so she can’t work out why inflation isn’t coming back.

It’s called a balance sheet recession Janet, you know, like Japan since 1991.

Jerome Powell is not looking at the debt overhang after 2008 and so thinks the US economy is fixed and raises interest rates.

Raising interest rates with all that debt in the economy will soon cause a downturn and there is no way he will get anywhere near normalising rates.

The poor old central bankers never stood a chance.

Where did it all go wrong?

Free market thinking took two separate paths in the 1930s.

We took the wrong path.

In the 1930s, Hayek was as the London School of Economics trying to put a new slant on old ideas.

In the 1940s, Hayek put together his theories of the markets being a mechanism for transmitting the collective wisdom of market participants around the world through pricing. It was never going to get into the mainstream until nearly everyone had forgotten what happened last time they believed in the markets, which occurred in the 1980s.

They needed some economics to support free market theory and 1920s neoclassical economics was just the ticket. After sticking some complex maths on top it could be passed off as new and scientific.

Wrapping it in a new ideology, neoliberalism, ensured no one would notice the 1920s neoclassical economics lurking underneath.

While Hayek was at the LSE, the free market thinkers at the University of Chicago were working out where it all went wrong in the 1920s.

The Chicago Plan was named after its strongest proponent, Henry Simons, from the University of Chicago.

He wanted free markets in every other area, but Government created money.

To get meaningful price signals from the markets they had to take away the bank’s ability to create money.

Henry Simons was a founder member of the Chicago School of Economics and he had worked out what was wrong with his beliefs in free markets in the 1930s.

Banks can inflate asset prices with the money they create from bank loans.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

Henry Simons and Irving Fisher supported the Chicago Plan to take away the bankers ability to create money.

“Simons envisioned banks that would have a choice of two types of holdings: long-term bonds and cash. Simultaneously, they would hold increased reserves, up to 100%. Simons saw this as beneficial in that its ultimate consequences would be the prevention of “bank-financed inflation of securities and real estate” through the leveraged creation of secondary forms of money.”

https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Henry_Calvert_Simons

Real estate lending was actually the biggest problem lending category leading to 1929.

Richard Vague had noticed real estate lending balloon from 5 trillion to 10 trillion from 2001 – 2007 and went back to look at the data before 1929.

Henry Simons and Irving Fisher supported the Chicago Plan to take away the bankers ability to create money.

“Stocks have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” Irving Fisher 1929.

This 1920’s neoclassical economist that believed in free markets knew this was a stable equilibrium. He became a laughing stock, but worked out where he had gone wrong.

Banks can inflate asset prices with the money they create from bank loans, and he knew his belief in free markets was dependent on the Chicago Plan, as he had worked out the cause of his earlier mistake.

Margin lending had inflated the US stock market to ridiculous levels.

The IMF re-visited the Chicago plan after 2008.

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12202.pdf

Why did it cause the US financial system to collapse?

Bankers get to create money out of nothing, through bank loans, and get to charge interest on it.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

What could possibly go wrong?

Bankers do need to ensure the vast majority of that money gets paid back, and this is where they keep falling flat on their faces. Banking requires prudent lending.

If someone can’t repay a loan, they need to repossess that asset and sell it to recoup that money. If they use bank loans to inflate asset prices they get into a world of trouble when those asset prices collapse.

As the real estate and stock market collapsed the banks became insolvent as their assets didn’t cover their liabilities.

They could no longer repossess and sell those assets to cover the outstanding loans and they do need to get most of the money they lend out back again to balance their books.

The banks become insolvent and collapsed, along with the US economy.

Long past time it were acknowledged that monetary policy has shot its bolt and that fiscal policy, industrial policy/credit guidance and capital controls are all in the ascendant.