The private equity industry has been pushing hard to get at a big pot of money: heretofore off-limits retail investors. The sense of urgency has increased as private equity has been unattractive on a risk-return basis for over a decade and principals of some firms have even taken to warning that performance will be even weaker in the future. To try to improve these flagging net returns, some large investors are starting to bring private equity in house to reduce private equity’s obscene fees and costs. So tapping into mom-and-pop investors is a hedge as well as an opportunity, now that there is reason for private equity managers to worry that their institutional investor marks may stop showing up for them.

Until now, regulations have kept private equity out of the retail market by prohibiting managers from accepting capital from individuals who lack significant net worth.

Private equity firms have succeeded in storming that barricade. The Department of Labor published a June 3 information letter that allows private equity funds, or more accurately funds of funds, to be included in certain 401(k) plan offerings, namely, target date funds and balanced funds. This is significant because despite the SEC regularly calling out bad practices with target date funds, they are the strategy used to manage the majority of 401(k) assets.

As as you can see if you read the letter, the Department of Labor parroted back significantly exaggerated or demonstrably false private equity claims about its merits.

Why Lack of Liquidity Is High on the List of Retail Investor Problems With Private Equity

There’s a lot not to like about this idea, including:

Super-high, significantly hidden, return-killing fees and costs that average 7% each and every year and will likely be at least 1% higher with the additional layer of fund of fund fees and costs

The false premise that private equity delivers superior returns or diversification

The great difficulty in meeting asset allocation target, when all the retail fund types for which private equity is authorized have set asset allocations

The dodgy history target date funds, of one of the types of funds permitted to include privae equity funds of funds

However, the biggest problem may prove to be that the lack of liquidity in private equity makes it inherently unsuitable for retail investors.

Because this is such a serious issue, we’ll discuss it first. “Lack of liquidity in private equity,’ even though that’s a conventional phrase, is misleading because it obscures the utter lack of investor control. When retail investors hear about illiquidity, they usually think of difficult-to-sell securities, or real estate, or art, where getting a desired price could take a while and turning the asset into money pronto might necessitate taking a big haircut.

In private equity, the investor contracts, the so-called limited partnership agreements, require the investors (“limited partners”) to provide a pre-set amount of funds,1 to the private equity fund manager (the “general partner”). But it’s not as if the limited partners hand that money over, as is the case with other types of investment products. Instead, the private equity general partner calls the money only to pay for his fees (which kick in immediately) or when he’s found a company to buy. Similarly, the general partner keeps investor funds until he’s sold the companies the fund bought, which means the general partner is also in control of when the limited partners get their money back.

Even though the prototypical life of a private equity fund is ten years, actual timetables are all over the map. For instance, the funds launched right before the financial crisis regularly took 12 to 15 years to wind up. And funds can drag on even longer. CalPERS has a fund dating to 1992 listed among its private equity holdings, along with others from the 1990s.

As many of you no doubt worked out, it’s hard to see how this squares with even the limited liquidity of 401(k) investments. Even though funds in 401(k) plans are typically valued every day, these plans also generally curb investor trading. 12 exchanges a year is a common limit. Nevertheless, if a fund that had a private equity component wasn’t doing well, investors could exit with their feet.

While the fund of funds managers said that they planned to provide for retail investor demands to cash out of their funds, it’s hard to see how that works. Despite the earnest representations of fund of fund managers to the Department of Labor that they could handle this impediment, high liquidity buffers (as in having investor monies in cash or cash equivalents) drag down returns, so the private equity fund of fund managers will have strong incentives to keep that to the minimum level, which increases the risk of mishap. Recall that hedge and money market funds have frozen redemption when they were unable to let investors out without dumping assets; there may not even be a bid on a fast enough turnaround for an attempted secondary market sale of a private equity holding, which would be the fallback mechanism for “providing investor liquidity.”

On top of that, whatever experience the big mutual fund families have with investor fund switching and liquidations is likely to be out the window with the coronacrisis. Even though it’s costly, individuals can and do tap into retirement accounts when they are bust, and it’s more probable now with the CARES Act waiving penalties and spreading out tax payments for many of those who do. And remember, many have lost health insurance along with their jobs, so even those who thought they had enough in reserves to scrape by might wind up tapping into their retirement piggy bank to pay medical bills.

Egregious Fees

7% in average annual fees and costs is a number that should not exist with any fund management product because it amounts to looting. And this is no exaggeration; Oxford professor Ludovic Phalippou, based on a review of so-called “monitoring fee” contracts that private equity general partners had the portfolio companies they control agree to pay, called them “money for nothing”.

As we’ll soon discuss, retail investors will get an even worse deal by virtue of paying an extra layer of fees and costs to fund of fund managers, on top of those 7% per annum typical fees and costs charged by individual funds themselves, offered by the likes of Blackstone, KKR, Apollo and Bain…as well as 401(k) fees, and fund fees (remember these private equity investment will sit inside other funds like target date funds that levy yet more charges).

How does private equity get away with this grifting? The short answer is the supposedly savvy, heavyweight limited partners, astonishingly, continue to invest in private equity when they have no idea of the total fees and costs.2

The big reason these fees are so opaque is that they are not charged to the investment fund, but to the portfolio companies that the general partners buy with the investors’ monies, and cowed investors don’t demand a full accounting of the cash that investors siphon off for themselves. For instance, in 2015, CalPERS admitted it had no idea what it was paying in “carry fees,” the prototypical 20% profit share that private equity funds retain when applicable before returning proceeds from sales of companies. CalPERS started pushing to get that information after the press piled on this lapse. But there are plenty of other opaque charges, and even a long list of abuses that led to one-off SEC fines and disgorgements that remain largely in place.

After these SEC enforcement actions, the most prominent trustees of some of the biggest and most experienced investors in private equity, namely public pension funds, begged the SEC to force private equity funds to provide more frequent disclosures and be more transparent about fees. Mind you, these are big money institutional investors which the SEC treats as “accredited investors,” meaning presumed to be able to take care of themselves. If financial heavyweights can’t get private equity firms to provide enough information for investors to feel comfortable about their holdings, why should retail investors, the dumbest dumb money, be sent to slaughter?

More specifically, the reason for this discomfort is that private equity funds have been caught out cheating investors in all sorts of sneaky ways. And with the SEC issuing only one-off (per type of abuse) slap-on-the-wrist fines, there’s no reason to believe the bad practices have diminished to a meaningful degree.

In other words, it is remarkable to see the SEC renounce one of its core principles for retail investors, which is full disclosure of fees and expenses, to give them the dubious privilege of getting past the private equity velvet rope.

Let’s look at how those fees add up:

7% on average for private equity fees and costs

An additional 1% for fund of fund management fees (this is conservative since it’s the level for institutional investors; retail investors will probably pay more).

Fund fees (remember that private equity investment is just a component in a larger fund?). For target date funds, Investopedia found that expense ratios ranged from 0.21% to over 0.6%. NerdWallet stated they averaged .51%. NerdWallet also found that “hybrid” funds, which would consist mainly of balanced funds, had an average expense ratio of .74%.

401(k) fees, which can be under 0.5% for a large plan and over 2% for a small one

So the total fees on that private equity holding would range from 8.7% to over 10.7%. To be clear, the party making money in this deal is not the chump, um, investor.

Romanticization and Rationalization of Mediocre Returns

Private equity has had two periods of sparkling returns: the 1980s, though the LBO crash, and vintage years 1995 to 1999. Everything else is brand fumes.

The situation only got worse after Alan Greenspan implemented negative real interest rates in the dot-bomb era and held them down for an unprecedented length of time. The resulting rush for return led large institutional investors to commit more to risky strategies, above all private equity and hedge funds. Private equity more than doubled its share of global equity since 2004.

Private equity returns are now the victim of too much money chasing too few deals. In keeping, for many years, private equity firm have also had high levels of “dry powder” meaning uninvested but committed capital. So private equity firms have more money lined up than they can handle, yet they propose to make returns even worse by luring retail investors to the table.

Remember the cardinal rule of investing: that higher risk investments should deliver high returns. Private equity has flouted that principle for over a decade.

During that time, and for nearly all sub-periods, private equity returns have failed to meet the conventional benchmark of the S&P 500 plus 300 basis points. CalPERS, to justify continuing to invest in private equity, first tried implementing “absolute returns” which meant ignoring risk when considering investments. When negative press coverage led them to abandon that idea, they simply lowered the benchmark, choosing a more forgiving equity index and then requiring a risk premium of only 150 basis points, half the former level.

If anything, saying that private equity is no longer earning an adequate premium to compensate for its risk (leverage and lack of liquidity) is too generous. Private equity hasn’t even been beating large capitalization stocks.

Oxford Professor Ludovic Phalippou, in a paper due out this week, An Inconvenient Fact: Private Equity Returns & The Billionaire Factory, shows that private equity has not beaten public equities. From a preview in Institutional Investor:

From 2010 to 2019, large cap indexes returned between 13.4 percent and 14.5 percent, matching the returns of private equity. Smaller public stocks returned between 14 and 16 percent.

So why do sophisticated institutions keep eagerly investing in private equity?

The rationalizations don’t hold up. One is that limited partners can be the Warren Buffetts of private equity and successfully out-compete all the other limited partners and wind up with the best funds. The basis for this dubious belief is that historically, the top quartile funds had a good propensity to wind up in the top quartile in their next fund, so it might be possible to pick winners. But persistence of top quartile performance ended in the early 2000s; you might as well throw darts now.

Another pretext is that private equity provides a useful profile of returns that is meaningfully different from that of other investments. Even if that were true, you could create a synthetic overlay for vastly less than what private equity charges.

But more important, the appearance of asset class diversification is due solely to faulty accounting. Investor returns depend on cashflows out and in, not bad bookkeeping.

First, private equity firms have been documented as regularly exaggerating their returns when about to raise a new fund, at the end of a fund’s life (when they only have dogs left that they haven’t written down) and during bad equity markets, where the private equity firms don’t write down the value of their investments as much as they should.

Bizarrely, everyone knows the private equity firms lie about their valuations when stock markets are down (the practice is called “smoothing”) and they treat this dishonesty as desirable because it makes returns look better than they are.

The other factor that makes private equity returns look different than those of stocks is that private equity funds report their results about a quarter late. Perversely, investors include them in the current quarter! If you adjust the timing of results and put private equity returns in the quarter in which they occurred, the correlation between public and private equity returns is very high.

Asset Allocation Problems

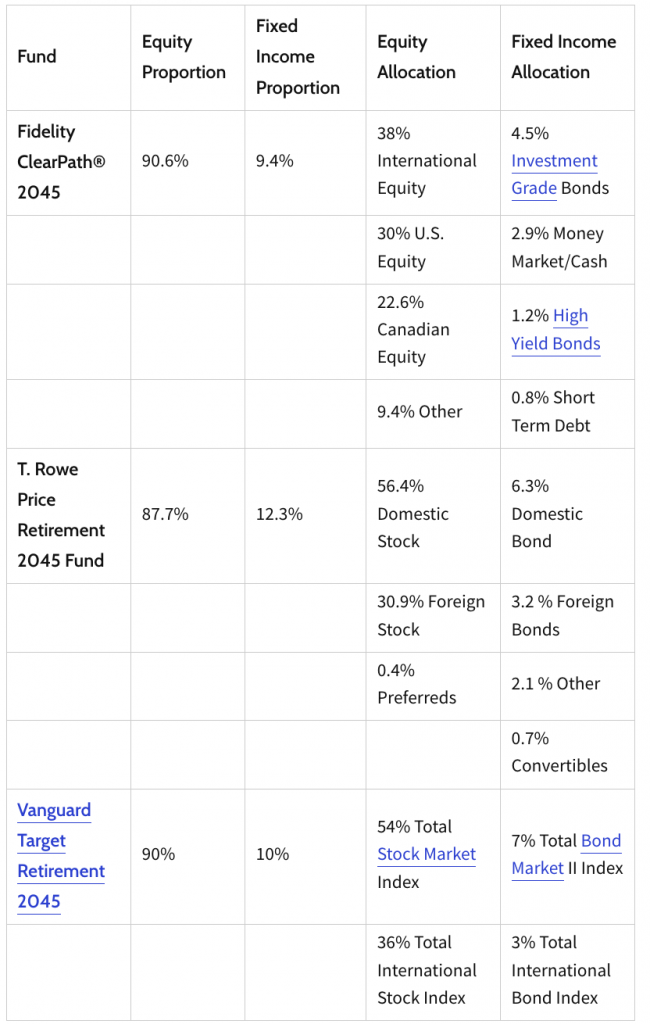

Both target date funds and balanced funds promise investors that they will hew to a particular asset allocation. Some examples from the Investopedia article on target date funds:

Since investors have no clear fix on when private equity firms will draw down their commitments and when they will give the money back, investors regularly show asset allocations that are significantly off their target. For instance, a November report by CalPERS’ private equity consultant Meketa howed the giant fund as nearly 1% below its 8% target. CalPERS was as much as 2% off the mark when its allocation was in the 10% to 12% range.

Now the fund managers will presumably gin up language that makes clear that the private equity asset allocation is aspirational as opposed to a firm level as with liquid securities. But then that leads to further disclosure of what happens when the private equity investment amount is above or below the stipulated level, as in what funds are used to make it up and how. In other words, this problem can be finessed, but will the disclosures match up to what happens?

Dodgy History of Target Date Funds

I plan to write again about target date funds, but it is telling to see private equity get its claws into the biggest pool of 401(k) funds, when it has been a regular target of the SEC for disclosure failings.

The short version is target date funds are one-stop shopping for investors who don’t want to think about managing their money. They are also the default if a plan participant has not chosen funds.

You pick your “target date” for retirement, decide how aggressive you want to be (not, moderately, or a lot), and the fund management family chooses funds for you (not surprisingly almost always from in-house product), reducing your risk level as your retirement approaches.

The target date funds typically allow you to change your target date and risk appetite midstream. For a longer overview, see here.

The SEC published an Investor Bulletin in 2010 about target date funds. Target date funds had gotten in a lot of trouble during the financial crisis due to insufficient disclosure of the risk of loss, and to not clarifying if they were “to” funds (where the risk level reached its lowest level at the target date) or “through” funds, where risk level was markedly above its eventual low, which it would hit years later. As the Department of Labor blandly put it:

These two types of TDFs would experience very different investment returns in the case of a drop in the equity markets near an investor’s retirement age.

In other words, investors in “through” funds took a bath when they though their risk was much lower than it actually turned out to be.

In 2019, it issued a Risk Alert, which is the SEC’s device for letting brokers and fund managers tidy up their affairs before the SEC examiners come a calling. The SEC criticized fund management families for virtually always putting investors in funds from the same fund group, even when they often didn’t perform as well as competitors’.

If you thought target date funds have had disclosure problems with conventional investments, just wait until you see them try to ‘splain how private equity fits (not!) in their so-called glide path.

The sad thing is it’s all too easy to see where this goes. Private equity fund managers will soon press for retail funds of funds that are just like the 401(k) offerings once they can say they’ve proven themselves with target date and balanced funds. And since fund beneficiaries and plan sponsors typically don’t find out something has gone wrong until it has gone really wrong, expect private equity to make further inroads.

One wonders why the SEC does not think it’s important to tell investors that private equity is in the business of firing people and too often bankrupting companies. Shouldn’t investors be warned that private equity’s tender ministrations, funded in a tiny way by his 401(k), could wind up lowering his paycheck or costing him his job? But no, in the belief system of the SEC, only investors can be victims of fraud and abuse, not wage earners who happen also to be investors.

_________

1 This is a simplification; see our Document Trove for examples of the computations.

2 Among other things, this means that they are systematically violating their fiduciary duty, since a fundamental obligation of a fiduciary is to evaluate the costs and risks of an investment strategy relative to its returns.

Remember the cardinal rule of investing: that higher risk investments should deliver high returns. Yves

Conversely, the zero-risk debt of monetary sovereigns like the US should return AT MOST zero percent minus overhead costs, i.e. NEGATIVE.

So NEGATIVE yields and interest are not strange at all but an ethical necessity to avoid welfare proportional to account balance.

But widows, orphans, pension plans!

That’s what legitimate welfare is for including Social Security. Not to mention an equal Citizen’s Dividend to replace all fiat creation for private interests.

That’s not true, because the only risk you do not have with UST is credit risk. You still have interest rate risk, inflation risk (unless you manage to buy indexed bonds, but those have problems of their own) etc. etc. .

The only glide path in evidence is that of investor returns toward zero.

The statement “Despite the earnest representations of fund of fund managers to the Department of Labor” assumes a level of honesty I’m not sure I would grant.

TDF are the default for the CalPERS offered 457 plan as well as the default for the 401, 457 and 403 plans offered by the State of California. I would assume that they are the default for many other deffer compensation plans.

Ahem, you appear not to recognize irony :-)

Yves, have you written about problems with “target date” funds before? If so, can you provide a link? I’d like to know more.

I have a tiny Roth with T. Rowe Price, so get their glossy advice/promotion magazine. They’ve been pushing Target Date funds in glowing terms for quite a while. Fortunately, I’ve long been past those targets, so didn’t become one myself!

No, I have never written about them but I plan to. I normally don’t write about retail products.

Just more runway foam. A big PE fund of funds is a mountain of financial “investments” – there’s not much there there. And what is there, the best stuff, is liquid, and gets sold and bought by insiders. The left over garbage from the usual cannibal feast of PE is chucked onto the mountain along with the few legitimate investments which serve to maintain the good reputation of all the crap. The crap filters down to the ground level where PE keeps its offices, like a layer of slime bacteria that works away day and night turning their useless dregs into a mulch of accounting blabber and glossy prospectuses which, in turn, slowly decays away – nothing left to see here, move along. No wonder the Fed keeps re-funding the big funds – it serves to reassure the SEC for one thing. It’s all financial recycling at its finest: reorganize, reduce, retool. Repeat. Until there is nothing left.

Thank you. Your description perfectly describes the process of collecting and sifting refuse, real garbage.

The good stuff never arrives at the garbage dump.

BlackRock took over our Washington State Deferred Compensation funds.

They have some targeted funds for retirement dates and some general funds.

The only funds available that are not owned by them are the savings pool and a bond fund.

How soon before Trump insists that the Federal Thrifts Savings Plan 401k must invest in this crap just like he forced out Kennedy for refusing to over-invest in International stocks which is a very underperforming fund. TSP is probably the biggest mutual fund(?) of its kind – an ocean of money to siphon.

I have a target date fund and I’m lucky if I even get 3%.

Thank you so much. I am not an expert, but I can study and digest this as a “little person”.

I don’t believe that you have properly interpreted the fee-load found by Ludovic Phalippou. While I understand your point, my read of his paper suggested that it was ~7% over the life of the investment, not on an annual basis. While these fees are significant, they are not quite as significant as 7% on an annual basis.

No, you are utterly incorrect. I have been corresponding personally with Phalippou for years. And as we wrote, shortly after Phalippou published his 7% estimate, CalPERS confirmed in 2015 at a private equity offsite. CalPERS has no incentive whatsoever to exaggerate private equity fees and costs. You can see the chart that prominently shows 7% as the average annualized cost of investing in private equity. At this point in time, CalPERS via its history of investing in private equity had even better data than Phalippou. Their fast confirmation of 7% per annum suggests if anything that their own data and estimates pointed to even higher total fees and costs.

Management fees alone, as Phalippou has repeatedly pointed out, are effectively 4% because only half the committed capital is actually at work at any point in time. Monitoring fees are on the order of 0.60% per annum of the invested amount. Then you have carry fees, transaction fees, the cost of captive consultants (the KKR-Capstone gimmick), group purchasing fees…..