Yves here. Get a cup of coffee. This post explains in depth how private debt has been a millstone to growth, and offers a series of proposals for restructuring of mortgage, student, and medical debt. Some readers may regard these plans as unduly modest. The flip side is that author Richard Vague is likely at the far edge of what is possible.

By Richard Vague, Governing Board of the Institute for New Economic Thinking; Managing Partner, Gabriel Investments. Originally published at DemocracyJournal.org

We were drowning in debt before the COVID-19 crisis, and now we are deluged in it.

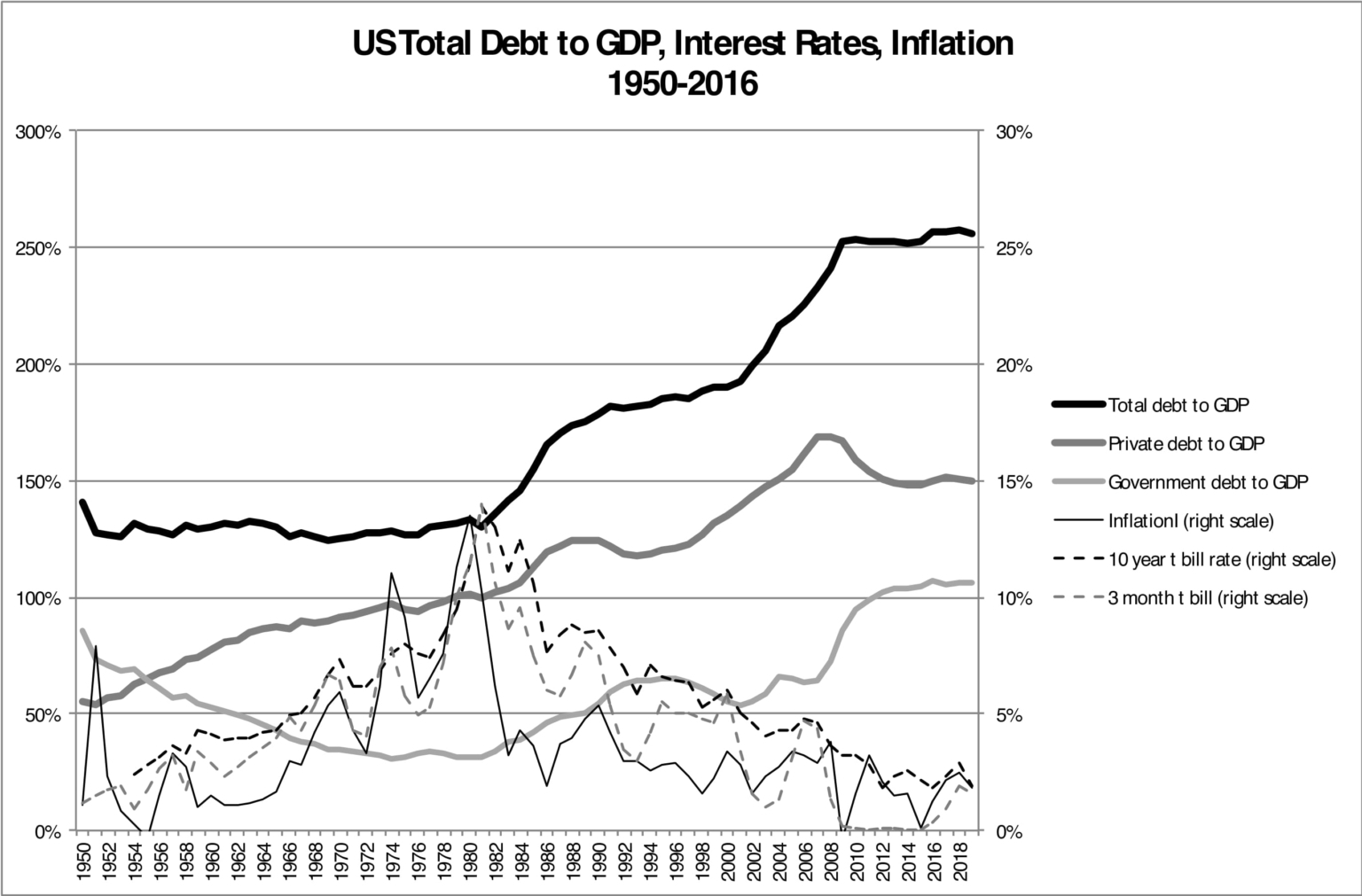

“Total debt” is the sum of public (government) and private-sector debt—and private-sector debt is comprised of business and household debt: for example, student loans, mortgages, auto loans, small business loans, and more. In 1951, total debt stood at 128 percent of our national GDP. By the end of 2019, total debt had doubled to 256 percent. (See Chart 1). Government debt has increased markedly and gets the most attention, but we should be more concerned about the rapid growth in private-sector debt. During this time span, government debt has gone from 74 percent to 106 percent of GDP, but private sector debt has grown even faster, tripling from 54 percent to 150 percent. This debt level burdens individuals and small businesses and stultifies economic growth.

Chart 1

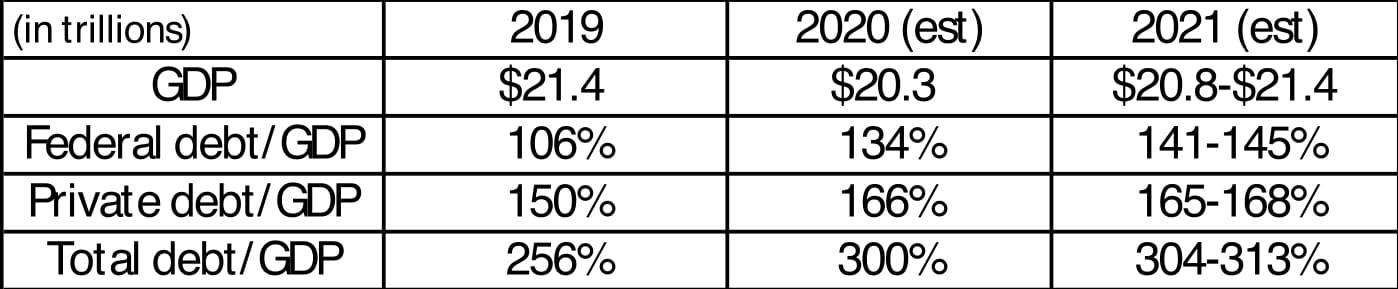

As both the government and American households and businesses use debt to fight the economic collapse caused by the pandemic, these debt ratios continue to spike. From January through May of 2020, private sector debt, which was already far too high, grew from 150 percent to 160 percent of GDP, though it is now moderating—and government debt climbed from 106 percent to 135 percent. By the end of 2021, these numbers could easily rise to over 160 percent and 140 percent, respectively, for a total of 300 percent or more of GDP (see Table A).

Table A

This huge debt overhang portends an extended period of stagnant and ever slower economic growth with falling living standards for millions of debt-burdened households. This is not another broadside against government spending and call for austerity—far from it. It’s a call to unburden American households mired in debt. Certain types of broad debt restructuring and forgiveness could help get us out of this debt trap and could be politically feasible. The proposals discussed in this article are for relieving the burden of mortgage debt, student debt, and more, along with a radically different proposal for government debt. These are intended to be provocative but possible, and food for thought, even for those who disagree.

The problem of private debt could not be more consequential. It’s been an underlying issue in several of the decade’s worst problems, from the 2008 global crisis and slow growth that followed the Great Recession to the discontent that led to Donald Trump’s election in 2016. Since minority communities have disproportionately felt the private debt burden, it has also been a part of the racial injustice that has only become more urgent and visible this year. And debt will hobble our efforts to move the economy forward during and after the pandemic.

GDP is in essence a measurement of our national income, so the ratio of private debt to GDP is the national equivalent to the “debt-to-income” ratio a lender uses when she evaluates your application for a car loan or a mortgage. The higher the ratio, the heavier your debt burden.

Debt growth that is faster than GDP growth is the normal state of affairs in developed economies, and is sometimes referred to as “financialization.”Private sector debt has accumulated continuously, rapidly, and insidiously, never truly reaching an equilibrium. The debt burden for individuals in almost every age group and for businesses of every size is increasing. In my investigations of household debt, it is not uncommon to find families with all of the following: mortgage debt greater than the value of their home, student loans still outstanding for the parents, and large debts tied to some unexpected surgery or other health-care expenses.

Private-sector loans are now asphyxiating households and businesses.

Families with high debt are far less able to pay for their own children’s college, build additions to their homes, buy new appliances, or start new businesses—the very types of things that power an economy forward. Likewise, businesses that carry too much debt are far less likely to expand, add product lines, or invest in research and development.

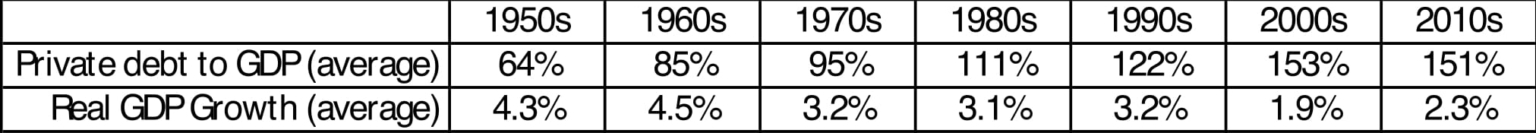

Private debt has enormous effects on American economy and society. And yet mainstream economists have rarely focused on it. Some economists have downplayed the adverse effect of this dramatic increase in household debt because, they maintain, the dramatic decline in interest rates offset it. But the debt service burden on households is still alarming, even taking into account lower rates. Though it has come down at least somewhat very recently, the “debt service ratio,” which estimates the payments consumers make on their debt in relation to their income, is still roughly 40 percent higher now than it was in the 1950s and ’60s—the two most vibrant growth decades in the post-World War II era (see Table B). It’s no coincidence that our highest growth decades since World War II came when households had their lowest debt service burden. The debt payment ratio story is similar for business.

Table B

This is the vicious dynamic at the heart of Middle America’s financial distress: Higher debt curbs spending, which constrains growth. Constrained growth suppresses wages. Lower wages constrain spending further.

So how can we reduce the ratio of private sector debt to GDP—which is another way of asking how can we reduce the burden of debt on households and businesses in relation to their income?

Certain solutions have been regularly invoked. Perhaps the most popular one is the proposition that we can grow our way out of debt. We’ve heard politicians and economists make this claim countless times, and it is a highly appealing idea, but a very uncommon one historically. This is known as “deleveraging,” and while modest deleveraging sometimes occurs, meaningful deleveraging to a level low enough to positively affect growth rates is truly rare.

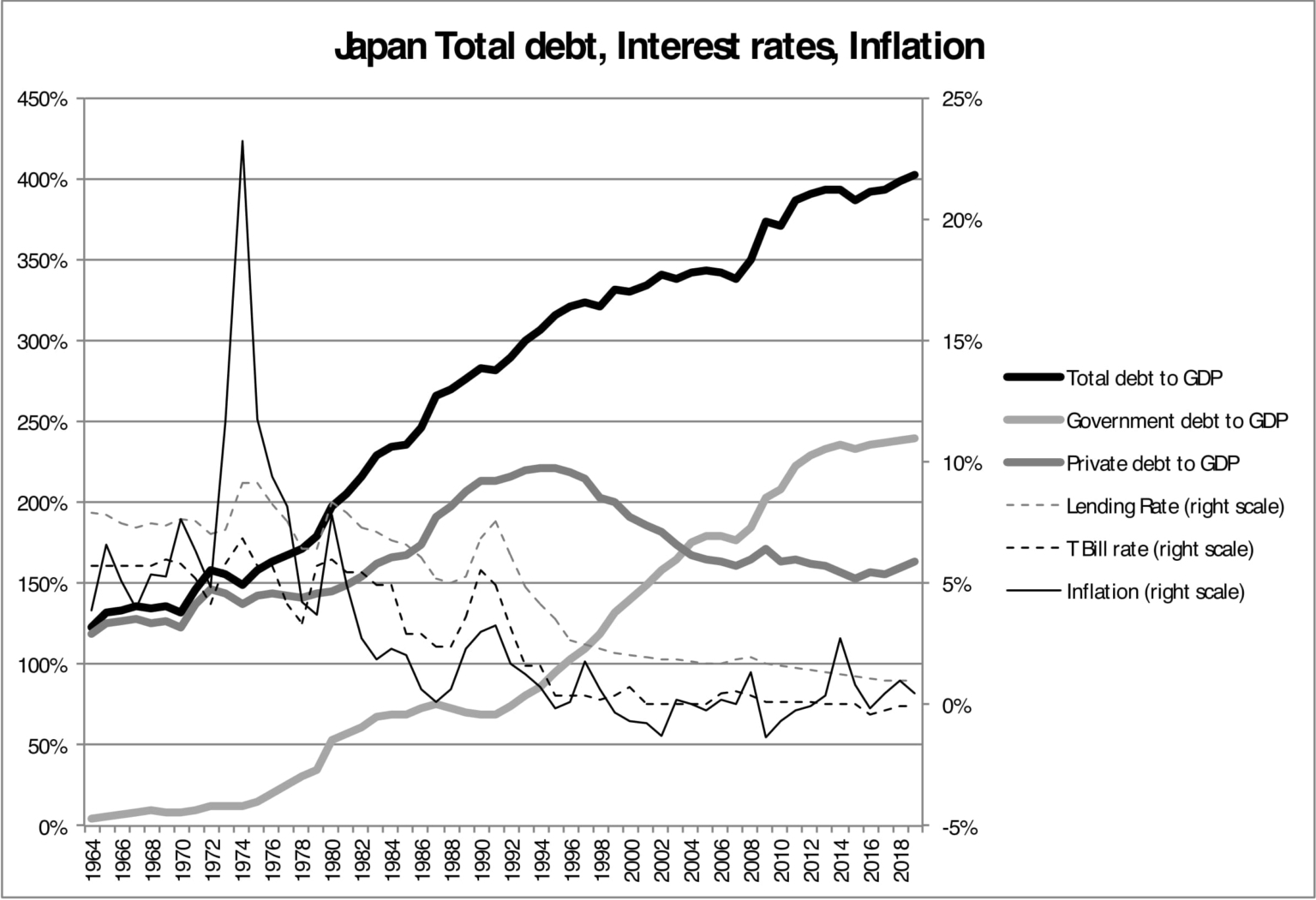

The most often-cited example of a country “growing out of its high government debt” was the United States after World War II. From 1950 to 1980, U.S. government debt to GDP did indeed fall from 86 percent to 32 percent, but that was only possible because of a massive re-leveraging of the private sector, where private debt vaulted from 55 percent to 101 percent of GDP. Without that massive private-sector debt growth, the improvement in government debt would not have occurred. This was more a trade-off that is best understood as the debt version of “out of one pocket and into the other.” The converse happens as well—private debt deleveraging generally only occurs when accompanied by massive public debt growth, as in Japan after its 1990s crisis.

Since 1950, in the top ten economies in the world, there have been no instances where private and public debt to GDP have both declined at least 10 percent within five years. Even when we look at smaller countries, it is very rare.

When all or any portion of the debt to GDP ratio does improve, it is generally due to one of three factors: 1) the “out of one pocket and into the other” trade-off between public and private debt, 2) a calamity, such as very high inflation or recessions and depressions, or 3) high net exports. This last option of high net exports is not feasible, since the United States has never achieved that high a level of exports. The scenario is also controversial because it depends on rising debt in another country that buys the exports. It would require years of sustained austerity. All the while, other countries are also attempting the same strategy, which undermines its effectiveness.

So, we can’t grow our way out of high debt. Can we inflate our way out of it?

It’s routinely claimed that we can, and although deleveraging through inflation is rare, it does sometimes work. But high inflation or hyperinflation is a cure worse than the disease. And there is no guarantee that it will work. During our country’s one recent major bout with inflation, from 1973 to 1982, total debt levels actually increased from 128 percent to 136 percent of GDP.

Furthermore, central banks have shown, over the last decade, that they may not even know how to create inflation. Even though they have employed the methods widely thought to cause high inflation, including low rates, high money supply growth, and massive deficit spending, inflation is running below the central banks’ target. If they struggle to increase or keep inflation at 2 percent, then what makes us think they can increase inflation to 5 percent or 10 percent for several years, the very minimum required to make a meaningful dent in the debt-to-GDP ratio (notwithstanding the temporary food inflation from COVID-based supply disruption)?

Economists have long had a misguided notion that high government debt growth and high money supply growth are the primary causes of inflation, yet there is almost no empirical support for this idea. Looking across all countries since World War II, there have been dozens of sustained periods of very high money supply and government debt growth. Very few were followed by high inflation, and many stretches of high inflation were not preceded by high money supply or high government debt growth.

This notion of inflation caused by money supply or debt is one of the great red herrings of economics. The fact is that, other things being equal, high levels of debt are disinflationary, even deflationary, because they suppress consumption and investment, and thus weaken aggregate demand.

So we cannot look to price inflation to solve the problem of high debt, either.

Finally, the most straightforward proposed solution: Why don’t consumers and businesses just pay down their debt? For two reasons. First, most of them simply can’t. If they had the resources to pay debt down, they wouldn’t have incurred the debt in the first place. But the second reason is more important: If consumers and businesses paid down debt en masse, it would crush the economy. That’s because the dollars used to pay debt down would largely be funded by a reduction in spending. Consumers now have $16.2 trillion in debt. An aggregate paydown of 5 percent of that debt would total $810 billion, and that would almost certainly come from an $810 billion-dollar reduction in spending. Since GDP is a measure of spending, it would bring a 4 percent collapse in GDP. That’s precisely what happened from 1929 to 1933 in the Great Depression, when a collective 20 percent paydown in loans, brought on by banks forcing repayment of loans and borrowers paying down loans, caused GDP to collapse by 45 percent.

We can’t grow our way out of the high private debt problem, we can’t inflate our way out of it, and we can’t pay it down.

So how can we reduce debt?

For private sector debt, the answer is: debt restructuring.

Debt restructuring is a modification of the terms of a loan that deals realistically with a borrower’s ability to pay in times of distress. Typically, the lender reduces the principal balance or the interest rate, or extends the term of the loan.

This action goes by a variety of names, including “debt forgiveness.” Historians sometimes refer to it as “jubilee,” a term used for household debt forgiveness decrees in ancient Israel that were similar to debt forgiveness in ancient Egypt, Babylon, and elsewhere. The widespread existence of this type of debt forgiveness in antiquity profoundly attests to the universality and persistence of this debt accumulation issue. Whether called “restructuring,” “forgiveness,” or “jubilee,” it is the only feasible way to reduce private sector debt when it accumulates to crushing levels in societies, and the only way to do so without severely damaging the economy.

In fact, giving households and small businesses debt relief would be an extraordinary boost to the economy, since it would free money now being used for debt service to be put instead toward investment and spending. Debt forgiveness translates directly into economic renewal and resurgence.

Debt restructuring already occurs routinely within individual lending institutions. Most have individuals or departments dedicated entirely to this type of effort, who work each day to reduce the principal or modify the terms of a given loan based on the borrower’s distress. However, to meaningfully impact debt numbers overall, “jubilee” needs to be implemented on a larger scale.

A growing list of politicians and economists have been advocating various large-scale forms of debt restructuring, and the pandemic has only amplified their message. Presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, for one, called for outright forgiveness for all student debt. There have also been calls, especially in the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession, for mortgage debt relief and the latitude to modify mortgages from such economists as Joseph Stiglitz and Mark Zandi.

But these recommendations have not been widely embraced, and have engendered uneasiness and opposition based on three main objections: fairness, cost, and the moral hazard that debt forgiveness might create.

On fairness: How can we forgive one person’s student debt, for example, when another person in a similar timeframe and in similar circumstances has fully paid theirs? For mortgages, consider the case of two neighbors, both with $240,000 homes, where one has a $300,000 mortgage because he bought at the height of the 2006 boom, and thus is $60,000 underwater, while the other has a $150,000 mortgage because she didn’t. How can we justify forgiving $60,000 of that first person’s mortgage, and not do as much for the second person? And how can this mortgage forgiveness be fair to renters, since they don’t get a dime?

The Tea Party, which became influential in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, began with protests against the unfairness of the Obama Administration’s $75 billion proposal to reduce the monthly payments of the nine million homeowners who were facing foreclosure. One ranting reporter on CNBC memorably questioned why he should be required to subsidize the mortgage of someone who had “made a mistake.”

Because of this fairness issue, some feel the only approach to jubilee is to simply give a check to everyone, along the lines of the $1,200 checks given out as part of the CARES Act at the beginning of the pandemic, but mandating that it be used to pay down debt. I applaud and endorse more support of this type. However, unless we give a much larger amount to everyone, for example $10,000, which would mean a multi-trillion-dollar expense, it is not going to meaningfully dent the student or mortgage debt problem, where the average debt amount is high at $35,000 and $200,000 respectively. A more targeted approach as proposed below can bring more relief for a lower cost where the need is most acute.

The second objection to jubilee is the high cost, and the related question of who pays that cost. In the cases just discussed, the lender bears the direct cost of debt forgiveness. In the aftermath of the Great Recession, there were so many troubled loans that forgiving them in many instances would have caused those lenders to fail. If instead the government steps in, many would ask why the taxpayer should bear this cost—which could run to tens or hundreds of billions of dollars or more. Even those who note that the government has the capacity to take this step may still justifiably question why funds should go to this program and not others.

The third objection is moral hazard. If someone gets bailed out of debt when they struggle, won’t that make them less prudent in their future borrowing habits, convinced that they will get bailed out again?

So, to get legislation enacted, jubilee programs need to be designed with awareness of these objections. Their sponsors must take into account the “Overton window”—the range of policies politically acceptable to the mainstream at any given moment.

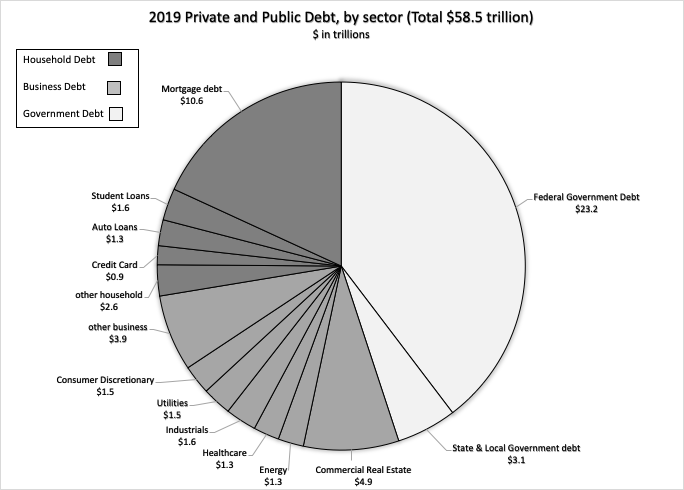

In my view, the areas of private debt most in need of relief, and achievable, are mortgage debt, student loans, health-care debt, and small business loans—the areas of excess debt that disproportionately impact the economy since they are among the largest components of private debt (as compared to smaller components such as credit card debt—See Chart 2). The ideas presented here illustrate the type of thinking needed.

Mortgage Debt Relief

In the aftermath of the Great Recession home values plunged steeply, and consequently over 10 million of the nation’s 52 million mortgages went underwater—meaning the value of their home was at least 10 percent lower than the amount of their mortgage. This compares to less than 2 million today. Mortgage debt is the largest area of household debt, thus problems here bring greater damage to the economy as a whole.

Chart 2

Here’s a possible program for forgiving the underwater portion of owner-occupied mortgaged properties: Let’s say you have a home with a $300,000 mortgage but the market value of the home is $240,000, such that the home is $60,000 underwater. If a lender were to write down the amount of that mortgage to the current market value of the home, they would normally have to take the entire $60,000 write down as a loss at that moment. For this reason, lenders are loath to write down a mortgage, especially if the borrower is current on payments, even if he is struggling mightily to stay current.

I propose a program that would allow a lender to write down the underwater portion of the mortgage over 30 years, instead of all at once, if that lender in turn immediately reduces the principal on the borrower’s mortgage by that same amount, and also proportionally reduces the monthly payment. There is regulatory precedent for such deferrals. It would be done at the borrower’s option. The lender would still be able to take the tax benefit in the current period, and the deferred amount would not be counted against capital or reserves.

In exchange for this benefit, the borrower would be required to give the lender some portion of the gain on the subsequent sale of the home, based on the ratio of the amount forgiven to the total mortgage. In this example, let’s say that is 30 percent. When the home is sold, the lender would get 30 percent of the gain. Including this feature in the program would directly address the fairness issue. Anyone willing to cede a portion of the gain on sale to the lender would be eligible to participate.

The features of only having to write-down 1/30th of the loss each year, but getting the full tax benefit of the loss, and also the eventual gain on sale, should make it attractive to lenders.

If this had been enacted in 2009, it would have provided significant relief to millions of homeowners and allowed many to remain in their homes. It could have been enacted for only a specific window of time, say, through 2012, and only for mortgages of less than $500,000 in size. There is less need today after all the refinancings that have since occurred, but it is still a powerful idea that could bring substantial relief to many.

Student Debt Relief

Student debt weighs like a millstone around the necks of millions of Americans for years after they have left college, deferring home buying, delaying household formation, and more. Conveniently, there is an existing program of debt forgiveness for students who choose careers in the public or not-for-profit sector that could be modified and expanded. In this existing program, students who serve in the public or not-for-profit sector and also make 120 consecutive payments on their debt can have the remainder of that debt forgiven.

Unfortunately, the government has taken a very narrow view of this program and disqualified many participants for minor infractions. Nevertheless, we do have this precedent. We can expand it by making it available to those who do not work in the not-for-profit sector if they do substantial volunteer work for a qualified not-for-profit institution.

I propose that if a student debt holder with a job in the private sector has made payments for 90 consecutive months, and also done volunteer community service for an approved government or not-for profit organization for 1,000 hours, then the remaining balance of that student’s loan would be forgiven. I would shorten the existing public sector worker program from 120 months to 90 months as well.

If the lender holding that loan is from the private sector, the government would then buy that loan and forgive it. This design addresses the issue of fairness by requiring a commitment from the borrower to make a meaningful, sustained contribution of their time and labor in civic or charitable work in order to qualify for the forgiveness.

Health-Care Debt Relief

Health-care debt has become a scourge. According to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, half of all overdue debt on credit reports in the United States is from medical debt. The Kaiser Family Foundation has reported that 26 percent of U.S. adults ages 18 to 64 say they or someone in their household had problems paying or were unable to pay medical bills in the past year. The Commonwealth Fund has found that 80 million Americans have problems with medical debt or bills.

It’s not surprising. Millions of families are uninsured, and those that are insured increasingly have deductibles as high as $3,000 to $5,000. In a country in which the Federal Reserve reports that four in ten adults would have difficulty covering an unexpected $400 expense, unplanned medical expenses and surprise medical bills can begin a debt chain reaction that puts a household in arrears on credit cards, auto loans, student loans, mortgages, and other debt, trapping them in a blizzard of late fees and collector calls and adding unbearable stress to their lives. The issue is so acute that some simply postpone needed medical procedures, which compounds their medical problems and increases future medical costs.

I propose a straightforward solution: a means-tested program whereby individuals with less than $75,000 in household income could apply for the government to reimburse them for any debt incurred for a select number of critical health-care expenses, including select procedures for diabetes, cancer, and heart disease.

Better yet, the government could introduce an overall catastrophic health insurance plan as part of an expanded health-care initiative, whereby people not otherwise covered for a select set of procedures would be covered, and people who are covered could have their deductibles reimbursed.

These are three powerful and programmatic approaches to debt jubilees. We can add to these a change to the system that would also improve the debt ratio: specifically, our nation’s bankruptcy laws. As a career lender, I have come to believe that thoughtful and appropriate types of relief in the form of bankruptcy laws result in healthy lender prudence, and that bankruptcy is therefore not only a way to cope with calamity, but also a self-regulating mechanism, a safety valve and check on the lending system.

During a number of periods of national financial distress in both the United States and elsewhere, bankruptcy laws have been enacted to allow for increased relief for debtors and to provide a more orderly basis for dealing with distressed debt. Some were intended as temporary measures and repealed after a few years. These include the Bankruptcy Acts of 1800 and 1841, occasioned by the financial crises of 1796 and 1837 and repealed in 1803 and 1843, respectively.

The COVID-19 crisis presents another moment of financial distress, and another opportunity to modify bankruptcy laws to address the extraordinarily high burden of student and mortgage debt. One suggested change would be to allow student debt to be discharged in bankruptcy. Another would be to allow the underwater portion of mortgages to be discharged in bankruptcy, while allowing borrowers to remain in those homes. Another could be more of a tilt toward debtor relief versus protection of collateral. Beyond these, legislative efforts to streamline the bankruptcy process could be a game-changer.

While there is always abuse under any bankruptcy regime, most who file for bankruptcy do not do so lightly. Thoughtful bankruptcy reforms such as these would both have a beneficial impact on the lives of Americans and on the nation’s household debt burden, which would translate into a powerful economic benefit.

Business Debt Relief

For the last debt area—business debt—one recommendation would be to modify somewhat the tax treatment of debt and equity. There are two primary ways that companies raise money. The first is through debt (a loan or a bond), and the second is through equity (selling shares of the company). Corporations, if they use debt, receive a tax deduction for much of the interest they pay. If they raise equity and pay a dividend on that equity, they don’t get a favorable tax deduction for that dividend payment, while the recipient of that dividend does pay tax, giving rise to the complaint of double taxation.

Thus, the tax code itself creates at least some bias toward the use of debt over equity and is at least part of the reason that leverage increasingly gets used to finance acquisitions of assets and other companies. A change in the tax code with less favorable treatment of debt and more favorable treatment of equity could reduce this bias toward debt, though full interest deductions should be preserved for smaller businesses.

A generation of excessive business debt has increasingly become a burden, and small businesses feel the brunt. I would propose a temporary program of debt relief of small business (defined as any business with annual sales of less than $10 million) similar to the mortgage program proposed above. For loans where the enterprise or collateral value had fallen below the loan value, a lender could write down all or part of the difference and write that loss off over 30 years as long as they restructured that debt to reduce principal to the borrower by that same amount. In exchange, the borrower would give the lender a negotiated portion of the gain on the sale of the business or its key assets. The lender could take the loss in the current year for tax purposes and the deferred loss would not be counted against that lender in calculating capital and reserve adequacy.

The benefit of these private debt jubilee programs would be a much-needed economic boost. A clean debt slate frees households for increased spending and investment that drives an economy forward. But more fundamentally, it would profoundly transform the lives of Americans: They would have much higher hopes that they could afford their children’s educations, keep their homes, and handle their health-care bills without being overwhelmed.

Jubilee has precedence not only in ancient civilizations but also in our more recent past. The U.S. acted to restructure or forgive public and private debt in Germany broadly after World War II, and that clean slate paved the way for Germany’s post-war economic miracle.

Jubilee programs would “flatten the curve” in the ratio of private debt to GDP and curb the insidious upward climb of debt.

Before we move to government debt, let’s consider two questions: Is private debt intrinsically bad? And why does it continually increase?

Economic life as we know it simply would not be possible without enormous amounts of private debt. It’s like water: indispensable, always there, and taken for granted and unnoticed except when there is dangerously too much or too little of it. People use debt to purchase cars, houses, and other major assets. Businesses such as supermarkets and retailers regularly use debt for their ongoing need to stock inventory. A manufacturer incurs debt to buy raw materials to turn into finished goods.

It’s not merely that the economy could not operate without private debt; it also could not grow without an increase in that debt. Debt is required to build new factories, create new products, or build new housing developments. That’s a major part of the reason why debt always grows as fast or faster than GDP. This is true across all major countries. It’s not a coincidence, nor is it something that could be avoided through greater prudence, because it is built into the system. Debt is necessary for growth; GDP growth is correlated to debt growth.

This is the paradox of debt: Debt can be beneficial and it is necessary for growth, but too much debt stifles growth and can bring financial crisis. Debt can bring benefit, but too much can bring calamity.

We can illustrate the necessity of debt for growth by imagining an economy that has only 10 people in it. One owns a supermarket, another owns apartments, another owns a bookstore, and so on. Each of them spends and also makes $50,000 each year. Thus, the GDP of the total economy is $500,000. No one starts with any savings.

How can this economy of 10 people grow? If Person #1 spends more on food, she would have to spend exactly that amount less on something else; for example, books. In that case, GDP for that economy stays at $500,000. However, Person #1 could borrow the money for the extra food, either from a bank or in the form of credit from the supermarket. In either case it is debt that supplies the extra money to grow the economy. Let’s say Person #1 borrows $5,000 to buy more food. In that case, GDP in that economy has increased to $505,000. It’s that straightforward.

This shows why growth requires new money—in this case money created by debt. The concepts economists often cite as causing growth such as “increased net production” or “increased velocity” all require new money in the form of debt. Generally, we can’t grow our way out of debt because growth requires debt. (Given this, it is not surprising that there is an emerging movement for “degrowth,” the rejection of the belief that our economy must grow.)

Our 10-person economy also shows why contracting debt shrinks an economy. If the next year, Person #1 has to pay back the loan in full, she will have to reduce spending to make that payment, which means her expenditures that year will only be $45,000. That means that GDP will now only be $495,000. Ouch.

Which leads us to one other critical fact. As our monetary system now works, new money in our economy is only created by debt.

It’s a fact that gets little attention. The government does not print money “out of thin air,” as if it is free money that comes out of nowhere, even though this allegation has been repeated so many times that it has seeped into popular consciousness. Instead, money is created by debt. Essentially all money creation comes only with the simultaneous creation of debt.

Let’s look at what truly happens. The government “prints money” by issuing Treasury securities. Those securities are debt that pay interest and have a maturity.

The Federal Reserve “prints money” when, through its “open market operations,” it buys Treasury securities from a given bank by crediting (adding to) that bank’s account at the Federal Reserve. This creation of money also simultaneously creates debt, since that credit to the bank’s account is a liability of the Federal Reserve that pays interest and has an immediate maturity.

Banks create money as well—by lending. When an individual goes to a bank to borrow $10,000 for college, the bank gives the proceeds of that loan via a deposit to that individual’s checking account. That deposit is new money that is created by that debt. That deposit is a new asset to the customer, and a new liability of the bank that has an immediate maturity.

These three things encompass essentially all of what is routinely thought of as money creation or “printing money,” and all three simultaneously create an equivalent liability—an equivalent amount of debt. It is a neglected key to understanding modern economies, and it is at the heart of why the total debt to GDP ratio gets perpetually higher. Historically, most of this volume has been from bank lending, followed by Treasury debt, and lastly by Fed “open market” buying.

Growth requires new money. All new money is created by debt. Therefore, all growth is predicated on debt-based money and thus debt grows as fast as, or faster than, GDP.

Add to that the several other factors that contribute strongly to the tendency for debt to accumulate: Debt accrues interest; lenders have a powerful financial incentive to increase lending; there is always a level of unrecognized bad or unproductive debt; and owners of assets, be those assets buildings or companies, have a tendency to use increased leverage to extract more value from these assets over time.

Fundamentally, I believe that it is problematic—and perhaps even absurd—to have an economic system built entirely on debt-based money. A system in which all the money is created by debt is unsustainable. As I will discuss, it builds up pressures within that system, drives inequality, brings price deflation and asset inflation, and leads to the amassing of debt that eventually slows growth.

Will we soon reach a limit on private debt to GDP? We are at or near the limit now, especially if rates trend higher, since with more debt, higher rates have a more damaging effect on the economy. At zero or negative rates, there would be little impediment to increased borrowing but also little incentive to lend for any but much riskier and thus higher rate loans, compounding systemic national risk. The outlook in any interest rate scenario is troubling.

We need ongoing ways to reduce private debt, or else debt levels will reach the point—as now—where they bring growth stagnation and an ever-deeper debt trap.

It’s true that debt forgiveness costs. There is no avoiding that. I would expect the cost of my proposed jubilee programs to be high but manageable. Much of that cost would be borne by the government, and thus show up as increased federal government deficits and debt.

That brings us to the subject of high federal government debt, which is an area much more visible and hotly debated.

We need to start most fundamentally with the question of whether high government debt is problematic. It has long been assumed to be so, and politicians often reinforce that idea. President Barack Obama once lamented that America is relying on “a credit card from the Bank of China,” and during the Great Recession, when a journalist asked him, “At what point do we run out of money?”, he responded, “We are out of money now.” The partial government shutdown in 2018 and early 2019, during which 800,000 workers went unpaid, was based on the presumed pernicious effects of higher government spending and debt.

This belief is widespread because a number of economists, including the authors of leading macroeconomic textbooks, like Greg Mankiw, have long taught that high government deficits and debt would lead to high inflation, crowd out private investment, stifle economic growth, and even cause a run on the dollar resulting in a financial crisis.

However, since 1981, the government has routinely posted large deficits, and government debt to GDP has more than tripled—and none of those feared and predicted consequences has come to pass. Likewise, the Japanese government has posted recurring deficits, and its debt has quadrupled relative to GDP—and none of these consequences has materialized there, either. During the entire 40-year explosion of government debt from 1981 to 2020, price inflation has plummeted, not increased; interest rates have collapsed, not risen; buyers for government debt have been plentiful, not scarce, as evidenced by those declining rates; and private sector spending has proceeded apace.

These dire prognostications about government debt haven’t materialized for one simple reason. It’s because the United States has monetary sovereignty, meaning that it issues its own currency, and borrows in its own currency—a status that has existed in full since it went off the gold standard in the early 1970s.

With this monetary sovereignty, the government is not limited in its ability to fund spending through debt. This is fundamental to understanding modern, developed economies. When the government does go into debt, it creates an equivalent increase in assets—and thus wealth—in the private sector. For example, if the government goes $1 trillion into debt, then that generally means that it has spent $1 trillion in the private sector, and the private sector now holds $1 trillion in new wealth on its own balance sheets. That wealth is sufficient and available to buy newly issued Treasury debt. Beyond that, the Federal Reserve stands ready to immediately purchase debt from bank buyers. For those reasons, among others, there will always be sufficient buyers for the Treasury’s debt.

Nevertheless, many still believe the specter of inflation—even hyperinflation—might be just around the corner. But it is more reasonable to believe that the specter around the corner is simply more disinflation. Rising debt may thus do the very opposite of what has long been taught and feared. From 1981 to 2019, while federal debt to GDP more than tripled, inflation dropped from 10 percent to 2 percent, and long-term Treasury interest rates fell in a spiky, uneven, but nevertheless sharply downward path from 14 percent to 2 percent.

That is 40 years of evidence that growing debt is part of what causes interest rates and inflation to go down, since a high burden of debt, especially private debt, stultifies economic growth.

This all lends credence to theories such as post-Keynesianism and Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), that for a country like the United States, which has monetary sovereignty and issues its own currency, there is little or no drawback to higher levels of government debt.

I generally agree with these notions and many other aspects of post-Keynesianism and MMT. But there is a consequence to rising debt that these theories don’t contemplate. Rising debt is not entirely without consequence. There is a limit. That limit, surprisingly, is likely the declining interest rates we described, which are brought on in part by this rising debt. That is the very opposite of what economics textbooks taught us to expect. In some markets, these rates have reached zero or negative rates.

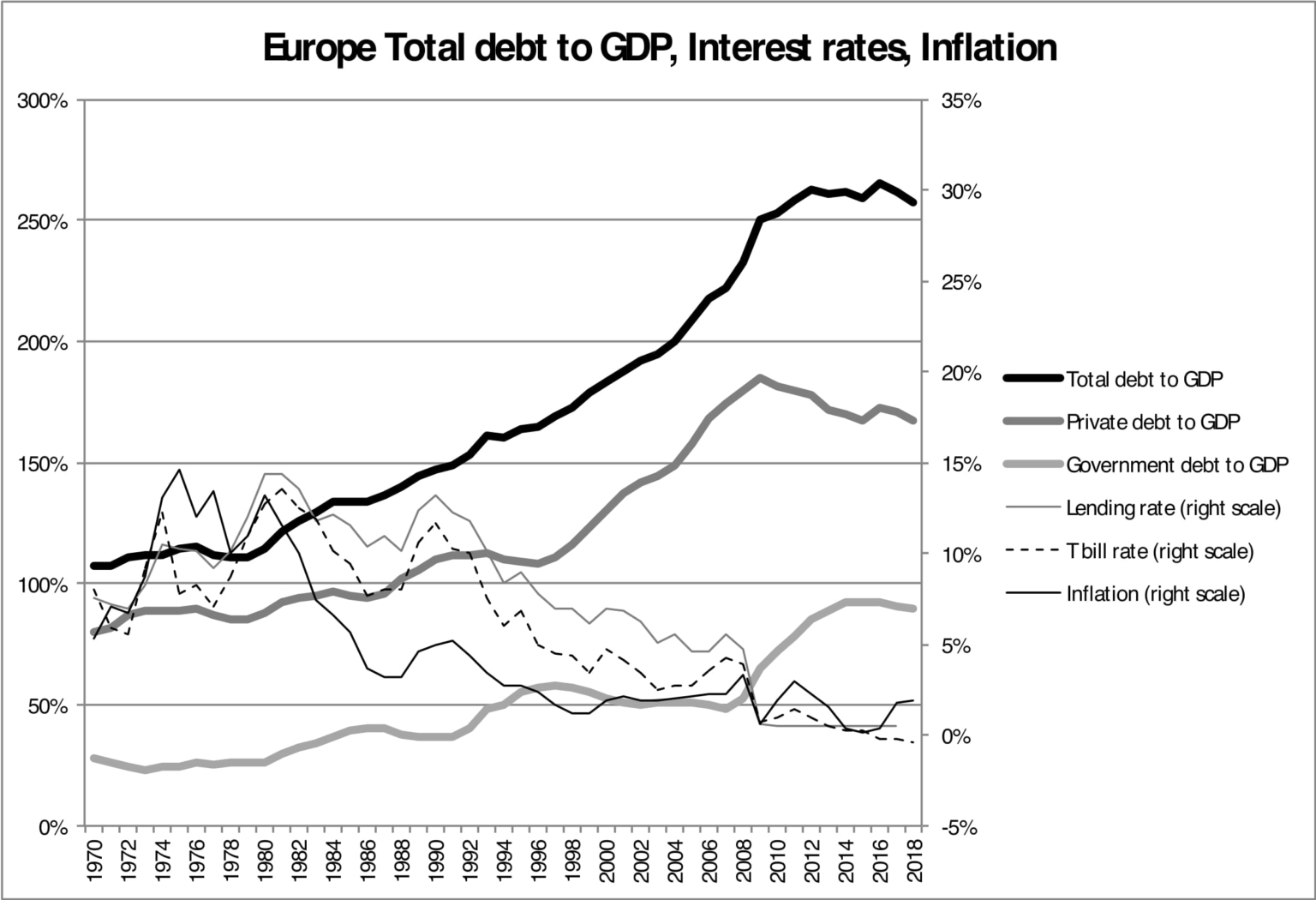

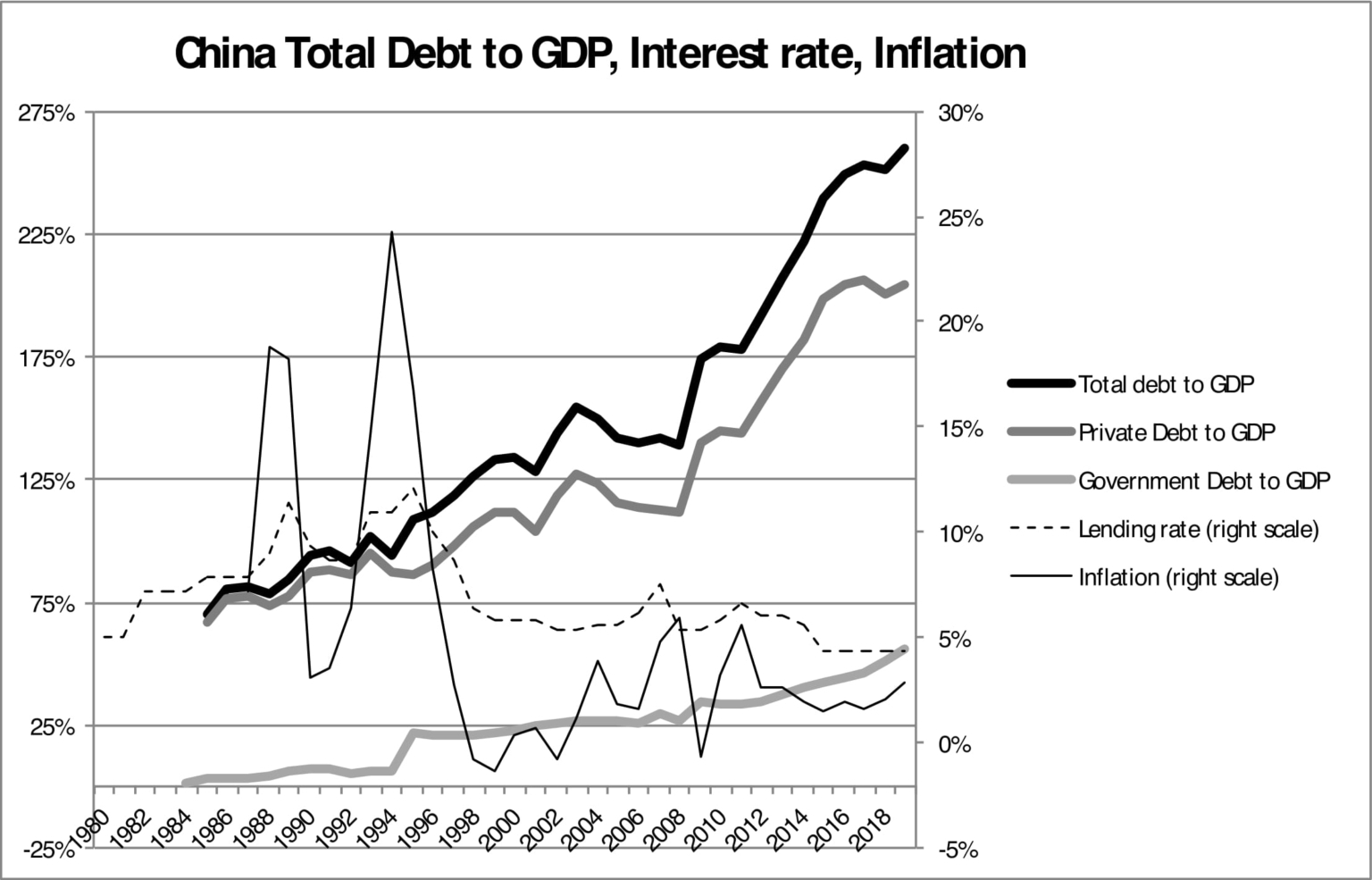

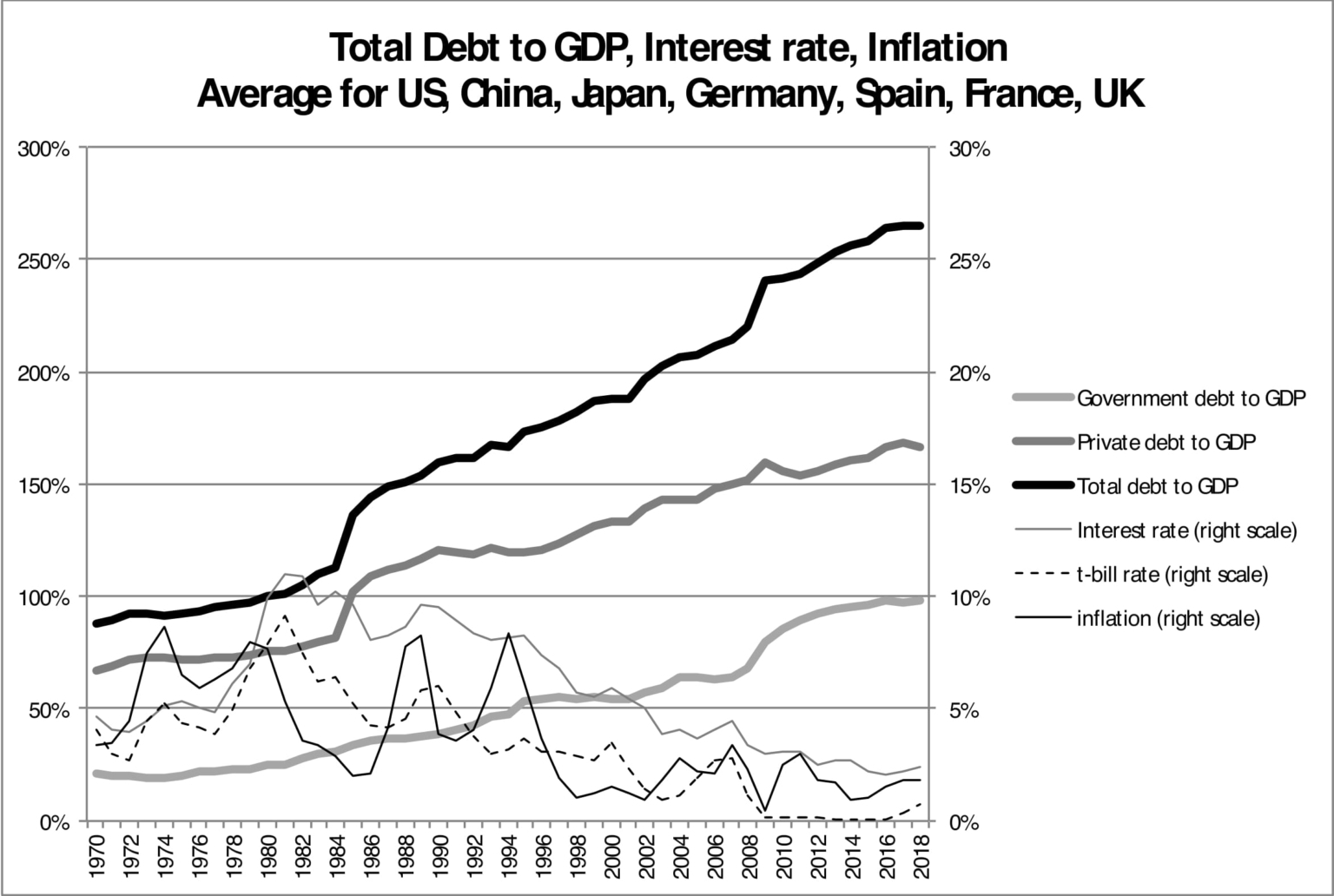

Look again at Chart 1 above and at Charts 3, 4, 5, and 6 below for Europe, China and Japan, which, together with the United States, account for 75 percent of all the debt issued in the world. These charts show exactly the same trend.

Chart 3

Chart 4

Chart 5

Chart 6

Now you might ask, what could be wrong with declining interest rates? Maybe the post-Keynesian and MMT theories are correct that we’ve got nothing to worry about from high government debt. And if it causes declining rates, then that sounds like a benefit. Negative rates, for example, if they were ever pervasive enough, would be a form of jubilee, since they result in a de facto reduction in debt outstanding.

Things are more complicated than that, however. The drawback to declining interest rates is that they bring an overallocation and misallocation of investments that cause asset bubbles—the rapid rise in the price of certain assets, most notably real estate and stocks. More importantly, they increase economic inequality. With lower rates, the rich get richer. The increasing GINI coefficient, a statistical measure of inequality, confirms this in the United States, Japan, and elsewhere.

Lower rates increase inequality in several ways. First, with low interest rates, things like money market funds and CDs have very low yields, and so investors increasingly move to real estate, stocks, and other riskier investments in search of higher returns, and that inflow of investment drives up their values. Since the top 10 percent of the country owns 62 percent of real estate and stocks, and average Americans hold comparatively little, this further widens the financial gulf between the haves and have nots. Thus, while low rates don’t bring price inflation, they do bring asset value inflation.

Second, for moderate- and lower-income groups that live off of their savings, especially retirees, lower rates mean lower income from safer investments such as government bonds and money market funds. With their income thus reduced, they either downsize their lives, or seek inappropriately risky investments, or both.

And even those net savers who do borrow get little benefit from these low rates, because they are not offered these rates by lenders, in part due to the high operating costs and higher risks associated with smaller loans. Instead they pay interest rates of 20 percent, 30 percent, 60 percent, or more on their unsecured loans.

Accumulating debt is likely a consequence and a symptom of growing inequality, because greater inequality means that more people have to borrow. And this consequence of inequality will persist even if interest rates and inflation decline no further.

Is there a limit to the issuance of government debt? Proponents of MMT have offered that inflation will signal that limit, yet since there is as much evidence that rising debt brings disinflation rather than inflation, that may not present itself, at least anytime soon. Witness Japan. Some suggest that the limit may play out through the value of the currency, in other words, a weakening dollar would at some point become a limit. But it would be difficult for the dollar to fall much because the rest of the developed world is also following the same path of expanding debt and declining interest rates.

So the answer, in short, is no. A government with monetary sovereignty has no technical limit to its ability to issue debt, but at moderate to high rates, interest costs would approach the size of the entire remainder of the federal budget—compounding the imperative to keep rates low. And at zero or negative rates, burgeoning government debt would turn the world upside down, with even greater levels of debt bringing an even greater imperative to keep rates low.

So, if higher government debt, including the vast sum amassed to battle COVID-19, is part of what drives interest rates lower, which in turn widens economic inequality, and causes dislocated and misallocated investment, this should motivate us to find ways to moderate government debt.

But how can we do this? We can’t simply wipe it out, since most government debt is held by individual investors, pension funds, and the Social Security Trust Fund, and not foreign governments. Canceling it, which has been suggested by some, would wipe out a significant part of U.S. household savings and would impair the government’s ability to borrow in the future and increase the rate it would pay on any such debt.

Nor, as we discussed above, can we grow or inflate our way out of government debt.

But what if there were a way for the government to create money without simultaneously creating a commensurate amount of debt?

There is.

This requires a brief digression into America’s own monetary past for precedents of just such a thing. The most prominent example comes from the Legal Tender Acts of the 1860s. To help fund the Civil War, Congress authorized the issuance of $450 million in new bills, which came to be known as “greenbacks.” It was a significant amount, totaling more than 5 percent of GDP and 14 percent of the cost of the Civil War, given that GDP reached over $8 billion and the total cost of the war was $3.3 billion. Greenbacks, of course, paid no interest and had no maturity. They gained acceptance as people saw they could be used to pay taxes.

For the years after the war until gold convertibility was restored in 1879, an average of roughly $350 million of these were in circulation. Yet, for those 14 years, inflation actually averaged negative 3.5 percent (after a three-year period of typically high war inflation due to heightened demand and decimated supplies). This was a starkly deflationary period. Greenbacks stayed in circulation through decades more of deflation.

We could do the paperless equivalent of this today by having the Treasury issue certificates that do not pay interest and do not have maturities. This would be a modern-day counterpart to the Legal Tender Acts that created greenbacks. Instruments that pay no interest and have no maturity are more like capital than debt. They are perpetual. So let’s call these new certificates U.S. Treasury Perpetual Certificates.

The Federal Reserve would buy these Perpetual Certificates by making a deposit into the Treasury’s account at the Fed. The accounting entries at the Federal Reserve would be a debit (increase) in certificates held by the Fed and a credit (increase) to the Treasury’s checking account at the Fed. The Treasury could then spend this money by writing checks and making transfers out of this account.

This idea is much in keeping with the trillion-dollar-coin idea proffered by Rohan Grey and other adherents to Modern Monetary Theory. Note that the use of Perpetual Certificates is one I would advocate only for large, developed economies.

Perpetuals would be a way to create money without creating debt, at least in the sense of debt that pays interest and has a maturity. That is a key and profound difference. It would improve the ratio of GDP to the government debt that does pay interest and have a maturity. It would obviate talk of burdening future generations with this debt. Because of these characteristics, I think that Perpetuals could more appropriately be referred to as “printing money,” just as this was the appropriate characterization of the greenbacks authorized by the Legal Tender Acts.

Perpetuals, in short, would create non-debt-based money. This would allow us to escape the debt trap built out of the relationship between debt, money, and economic growth I have described.

Take a look again at Table A. If we were to issue $1 trillion in Perpetuals this year and next in lieu of an equivalent amount of conventional Treasury securities, our government debt-to-GDP ratio at the end of 2021 would be 134 percent instead of 143 percent. If we were to issue that much for each of the next five years, again in lieu of an equivalent amount of conventional securities, the ratio to GDP at year end 2024 would be 129 percent instead of 150 percent.

That would mean less downward pressure on interest rates. Less inequality. And a lower percentage of the Federal budget allocated to interest payments.

Earlier in this article, I mentioned the cost of the jubilee programs I have proposed, and estimated that their cost would be high but manageable. They would be especially manageable if we used Perpetuals. In fact, Perpetuals are ideally suited for just such needs as jubilee programs, COVID-19 related stimulus, and the stimulus strategy referred to as “helicopter money.” The term “helicopter money” means different things to different people, but most often refers to programs where the government broadly issues checks to people as a form of stimulus, like the $1,200 checks dispensed in the CARES Act. If the helicopter money is funded by conventional Treasury securities, it increases U.S. government debt. If it is funded by Perpetuals, it does not.

Perpetuals can thus be a powerful mechanism for righting our economic course.

Everything has a downside, of course, including Perpetuals. It is likely that this downside is inflation. We have already argued that, contrary to received wisdom, issuing more government debt has led to lower inflation. But this has been true in the past because the interest rate obligation and maturity aspect of Treasuries serve as an accountability mechanism by requiring that interest be paid every six months and that principal is fully due at a specific point in time. Perpetuals do not have that same accountability mechanism or discipline. Therefore, we might justifiably worry that creating money without interest rate or maturity would indeed lead to inflation.

But we can avoid much of this worry by putting appropriate limits on the use of Perpetuals. We already have evidence that issuing this type of money in controlled amounts does not create inflation. We know this from the Civil War example, where for almost the entire period in which greenbacks were in circulation and unconvertible, inflation was negative 3.5 percent.

The key to avoiding inflation with Perpetuals may come down to volume and scale. It may very well be a linear relationship: the more non-debt-based money, the more inflation. Low amounts of something like greenbacks or Perpetuals would result in little if any inflation; medium amounts—say, 25 percent to 75 percent of GDP—would bring moderate inflation, and high amounts—say, 100 percent of GDP for several consecutive years—would bring high inflation. Thus, establishing the correct titration of Perpetuals into the money stream would limit the threat of inflation.

And a somewhat higher level of inflation might not be that bad a thing at this moment, when some central banks have been trying to engender it with limited success. After all, even slight inflation equally slightly erodes the burden of debt.

The bottom line is that we should be judicious in the issuance of Perpetuals. To do this, we should impose some legislative limits; for example, a cap on issuance of 5 percent of GDP in any one year with a cumulative cap of 25 percent of GDP.

This approach deserves strong consideration, because currently, all money in our system is created by debt and that is a major reason why debt always climbs in relation to GDP.

We need a balance between debt-based money and non-debt-based money. It may be that such a balance is the healthier and more technically sound way of managing monetary policy in today’s world.

This article describes the world we are moving toward, what some call the “Japanification” of America, with sky-high debt levels and desultory growth. That is unless there is broad-based and radical new thinking on debt restructuring. And that is the imperative for jubilee.

With the strategy outlined here, we would accomplish what has never been accomplished in recent economic history—arrest the otherwise inexorable rise in debt to GDP while maintaining growth and avoiding calamity.

Private sector debt to GDP, which is now destined to rise to the 165 percent to 170 percent range by the mid-2020s and keep rising, could instead be below 150 percent and keep falling. What is effectively the debt servitude of millions of Americans would be gone. With this, the private sector could more easily resume its role as driver of growth and prosperity. Likewise, public sector debt to GDP, instead of rising to and passing 150 percent, would be below 130 percent and falling.

All while America keeps growing.

This is the new world we should be endeavoring to attain.

This is meaty indeed – I haven’t had the time to go through in detail, but there are lots of interesting ideas here. Its good to see someone thinking beyond just ‘debt jubilee’ and ‘monetise it all’, to the actual detail of how you could prepare a politically palatable series of proposals. The big obstacle that I can see is that people who are largely debt free will be deeply resentful at what they see as their reckless neighbours getting off scot free. No proposal that doesn’t address this will ever get political support, even with a genuinely progressive government.

In connection with this, Michael Pettis has written quite a bit on twitter over the issues with debt write downs in China. In theory, the Chinese government should find it far easier than the US or Europe to simply write off all bad debt that is holding down the system (and there is a massive problem of private indebtedness in China), but as he points out, the issue is the other side of the balance sheet. Someone has to take the ‘cut’, at least on paper, and the the political problem, even in a dictatorship, is working out who ends up on the wrong side and persuading them not to fight it. A lot of creative thinking needs to be done to work out how to set the principle in to practice.

“The big obstacle that I can see is that people who are largely debt free will be deeply resentful at what they see as their reckless neighbours getting off scot free.”

Exactly. As someone who has no debt, been saving a long time to buy a house, been pummeled by low interest rates, a stimulus that only focuses on getting people out of a hole, they had a big part of digging themselves, is highly insulting. I am self employed, so the criteria to getting a mortgage are proportionally higher than someone taking home a W2 (not sure why, as I have more control over my income stream). To think that I would be competing with proliferate numbers of newly-freed spenders, after years of saving at zero interest, would be a bit much in again ‘taking one for the team’ for economic growth for the masses.

Sometimes you have to accept things like this. Real Christians would approve it in the basis of mercy and forgiveness but if you want a practical example, take a look at Ireland. It was wracked by bombings and shootings for over two decades until all sides decided to give peace a chance. But to do so meant releasing prisoners who were guilty of these crimes – though to their fellows, they were actually soldiers doing their part. So along the lines of your objection over debt forgiveness, would you have released those prisoners for a settled peace or would you have said no, justice demands we keep them even if it means another several more decades of The Troubles?

I agree that at times there will be things for the greater good that one must accept. Like wearing masks. I am not so onboard with the example of Ireland though. Over different time spans, forgiveness to soldiers seems fairly universal (as it should be) – witness re-unions between soldiers of WW2, Vietnam, over recent years. The analogy doesn’t really apply here.

I disagree with targeting debtors at the bottom of the income scale. If you are going to do anything with those at the bottom of the income scale, make it universal – and pull it from the tails in the upper ranges of the income/wealth distribution.

Debt jubilees, as opposed to universal redistribution, are yet another tool to divide those at the bottom – no different than race, religion, safety/law, etc.

I’d add that Real Christians understand the importance of the parable of the Prodigal Son is that the deserving don’t always get what they deserve. The prodigal got the fatted calf. The “good” brother didn’t. There are other parables like this, for example the master who pays his vineyard workers the same for a full day as he does workers who only work part of the day.

“Deserving” or “fairness” is something mature, sane people take with at least a grain of salt.

We do NOT have to accept things like this.

The answer is simple: Universal Basic Bailout (UBB), by which everyone gets an equivalent lump sum, to spend as needed. The highly indebted can spend it on paying down their debts. (And perhaps this should be enforced by the UBB program; i.e. money MUST be used first to pay down outstanding debts, if any.) Those who are not indebted can use the money for savings, investment, starting a new business, buying a home, or whatever. Perfectly fair and free from moral hazard, unlike debt jubilee which rewards historic improvidence.

+100

The people in the most debt have had to pay the most interest. Stop proposing linar solutions to exponential problems.

Run an amortization calculator on a 10 year, $10,000 loan at 1% interest and again at 20% interest. The total payments on the second loan are nearly 2x the payments on the first.

High interest rates cause massive inefficiency. You don’t have to outright forgive a loan to take it from nonperforming to performing. There is a region where just lowering the rate will rehabilitate your debtor.

Of course, that’s exactly the opposite of the decision that the financial system we have today is set up to do. At the first hint of trouble, lenders jack rates up as a signal to “pay me first”.

70% of voters want M4A but politicians won’t give them that, yet they still vote for them.

In other words, who cares what voters think? Neither of the two ruling parties in the US regime seems to. Or need to. Political support is gained by politicians and their MSM propaganda arm telling voters what to support, even if the voters don’t support that, or the politicians support the opposite. Debt forgiveness is very feasible and not political suicide. Politicians in favor of it simply need to lie, or be buddies with Maddow or Carlson, or rely on the infamous 45-second memory of the typical American voter.

At the end of the “day” is the debt-induced parasitic Plootocratic construct yet in place?

Is any economic renewal merely a two-out triple, only to get stranded on third?

The debt free are already something of an aristocracy, whether they want to admit it or not.

And if you are working, or own a small business, you will benefit from the spending power of those made solvent by the debt jubilee — their spending becomes your income.

The only argument against the jubilee comes from the oligarchs (descendants of the ancient rural userers) who depend upon indebting their fellow citizens in order to enrich themselves and retain their political power.

Really enjoyed the article.

However, I think the core problem is low wages / income and inequality.

Just as an example, when I was young, college was inexpensive. Making it loan based seems to have only increased the costs exponentially, with no corresponding increases in income derived there from.

Read CEPR for example after example of how monopoly and economic rents extract resources from the less well off and redirect resources to the rich. If the political power balance is not addressed, IMHO the inequality and problems associated with inequality continue.

As the author himself notes, low interest rates do as much harm as good. The idea of producing dollars is fine, but if one doesn’t address WHO GETS the dollars, I would suggest the value of those dollars will all be hoovered up by the rich. It is unfortunate that the graphs pretty much only go back to about 1970. I suspect that debt was not a problem in the 50’s and 60’s due to labor union power. As labor power waned, debt has been used to support demand – but as the author notes, lots of problems with that.

Very much like you I have enjoyed the article and recall that in the context of Hudson’s posts I wrote before that the epidemic is indeed making debt forgiveness a must. Yes, a must so that the reasons so often used against it no longer stand to scrutiny. Particularly the fairness issue: ‘How can we forgive one person’s student debt, for example, when another person in a similar time frame and in similar circumstances has fully paid theirs? The issue of undeserved comparative advantage. If this argument is to be used as a rule, there could be many other situations where a few benefit from similarly undeserved advantages. The rescue of so-called TBTF entities comes to mind as an example. Yo see, the TBTF serves as a reason, or an excuse to pardon for the moral hazard.

The question is what is to be done when the debt burden is so high that everybody losses, even those that managed to pay theirs. For instance, I have no mortgage, neither any other kind of debt, but my professional activity depends very much on the debt burden of SMEs. If it is very high, most won’t be confident to do the investments I propose even if I can demonstrate with numbers it is one of the most profitable investments a company can try. I offer photovoltaic installations for self-consumption. I propose then another acronym that could do the same trick as TBTF: provide a, in my opinion, better reason for debt forgiveness: ZBD: Zombified By Debt or ABD: Alienated By Debt. In the current situation we could add Alienated By Covid & Debt (ABC&D), a social disease so widespread to be systemic. Systemic and with a more profound impact than the failure of oversized financial entities.

Me too. An indebtedness crisis is the other size of an long running underemployment and underpayed crisis. You don’t get one without first long having the other.

The laws of neo-liberalism.

Law #1, Never take wealth away from wealthy people.

Law #2, Never take debt away from poor people.

#NailedIt

?

and of course…

Law#3 Never stop enforcing laws 1&2 with violence and the threat of physical harm/death to those that actually attempt to change this system.

aka Pareto Optimality – all ethical positions are renounced except one – private rent taking is sacred.

Very concise. I find myself agreeing with articles like this and saying to myself as I read them ‘yes, we must do this. It is only sane.’ And then I snap out of the stupor and think to myself ‘can anyone seriously picture any of this ever happening here?’ Schumer, Pelosi, Trump, Kamala, McConnell, blah blah blah endless list. Never

After this election is over, the task will be to ensure some of those people lose in the primary to leftists.

The point, surely, is that debt is power. I don’t doubt that many, if not most, of these ideas are feasible with political will. But it’s the political will bit that is the problem. It’s true that in many countries, private debt is strangling economic growth, and that forgiving debt would greatly help matters, but actually the 1% and their political front-things don’t actually want economic growth (they are doing fine anyway thank you) and specifically thy don’t want ordinary people to have fewer debts, and therefore more spending power, as opposed to needing to borrow, since that would recalibrate the balance of economic power. As Nitzan and Bichler have shown, capital is essentially about power. And the easiest way to accumulate capital, and thus power, is to impose debt on others. I can’t see this changing.

Though you are quite right, debt is power, at some point a sensible policymaker should realise that too much debt weakens the position of the whole country. The Powers That Be might realise they are becoming the Powers in the Desert, nothing else to extract there. Nothing really valuable. Not funny any more. Difficult, but there is a way to change.

power yes, but mostly it’s not about making money off a debt, they already have “money” up the yang yang; it is all about who controls the debt. That control is everything to them. You control the debt and you control everything. Also, on the other side of every debt is an asset. You eliminate the asset and you will have successfully ruined the entire economy. What could possibly remain? That’s why bankruptcy exist. Think about it. Everything is a large swath.

No, the easiest way to accumulate capital is to take on debt yourself to buy assets, get all the upside, and then dump the assets on some poor slob and use your relationships/ social capital to wipe your debt when you’re done.

Many propositions go in the right directions, so it is an useful paper.

I take issue however with this oft repeated trope that businesses need debt to grow. The author, by embracing MMT is nearly there, but fails to endeavour the last step : once enough debt free money is issued by the government, business and individuals don’t need debt any more because this money that the government printed is already in their pocket !

Inflation from money printing can be tamed by adding more and more constraint in the banking sector (such as the prohibition of maturity transformation and a postal checking service where deposits would be fully backed by debt free money) to slow the velocity of the increased monetary aggregate. Eventually, lending disappears and you have only left equity underwriters, unleveraged private equity and VC funding.

Once businesses have enough free money in their pocket, they don’t need to conduct business or perform any function that benefits society, because society is no longer the customer. They will downsize to a shell company and focus on Just collecting the free money. If the government wants its money back, simply declare bankruptcy.

Between the Trump tax cuts and the rampant binge of borrowing money in order to do stock buybacks, we are halfway there already. If 20% of companies are zombie companies, this is their raison d’etre today.

We don’t need ‘perpetual dollars’ we already have them. Just drop the word ‘perpetual’ and you know the answer already exists in our current system. Congress creates new dollars every time it pays a bill. That’s how the bills get paid. Just as ‘greenbacks’ did the job funding the Civil War. Lincoln said he feared the New York bankers more than he feared the rebel soldiers. So, insofar as the public debt is concerned the Feds should allow most of it to ‘roll off’ over time without replacing it with new debt. Congress has no need for debt to fund its spending. This ‘roll off’ would have zero impact on Congressional ability to spend. And what is ‘unfair’ with demanding the One Percent relinquish some of that unnecessary debt we created just for them. It was a 4 decade subsidy program for the One Percent, after all. How do you think the One Percent came about? Tax codes written to encourage debt. Tax windfall reductions to the One Percent. Subsidies in the form of the federal government financing the pollution messes private corporations make. So much for the Profit and Loss bookkeeping rules. Much of this wealth, looked at honestly, was unearned. It should be ‘clawed back.’ That would lessen income inequity, wouldn’t it. And unemployment is a political choice made by Congress. Our real enemy is ignorance.

I too was puzzled by the author’s focus on perpetuals. It seems to me you simply need to allow the treasury to run an unlimited overdraft at the central bank. Currency holdings would just increase through substantial increases in direct federal government spending or by the federal government funding the spending of lower levels of government.

Perpetuals allow the Central Bank to drain reserves from the banking system by selling them with a promise to buy them back at a profit for the buyer (reverse repro).

But this is a risk-free gain for the buyer and is thus welfare proportional to the amount of perpetuals bought.

Learned a lot from this, thanks. My impression of these bonds is mostly that they give a lever for investors to demand more “pain and suffering” for the masses. Was that the term Biden used, to reassure some investor types? It pains rich people to see the masses stably employed, relaxed, and healthy.

“Debt is necessary. ” I’m sure that premise pleases the bankers who fund INET, but it’s where I stopped reading.

Even if debt were necessary, positive interest isn’t necessary since the loans can be over-collateralized to compensate for risk.

I interpret this statement on Vague’s part to mean that as currently constituted, US law requires money creation by the Fed to be accompanied by bonds issued to match. The implication is that these bonds pay interest, though in theory the interest rate could be zero.

If the law were changed to allow overt money finance, then money creation could be arranged without bond sales — and cash is a sort of zero coupon “perpetual.” In this case the “debt” is simply a record of tax credits (which is another way to think of currency) not yet redeemed.

All of which is to say, GramSci, that Vague likely thinks of debt in terms rather different than yours.

Interesting.

I would go further though.

Wipe out half of all mortgage debt. At the option of the borrower

Reduce student loans to 1/4 of existing debt. At the option of the borrower

Cap credit interest rates

Move to a national healthcare plan that prevents costs from exceeding some cap relative to income

Require that anyone who accepts the debt reductions accept no being allowed to take out new debt that would exceed 10% of their income for a period of 10 years.

Create a minimum rate for savings accounts.

It will just happen again. The structural problem is that incomes for the bottom portion of the economy are too low.

Which is to say that the one-time jubilee is necessary, but insufficient. It must either be accompanied by structural changes to “predistribution” or else the jubilee must be repeated periodically — in antiquity the latter approach was adopted.

“the rapid rise in the price of certain assets, most notably real estate and stocks.” – that rapid rise in real estate and stocks is not counted as inflation!!!!???

As for rising real estate/land prices… in my opinion – it drives the inflation of all other products and services since they all occur on this planet.

As for stocks – beyond the initial investment that pays out to the business (with a big chunk played off by the big gamblers at the table) the remaining secondary are like baseball cards played in a tulip market – it may lower costs for raising capital for businesses but it is usually played like chips on a table and to the benifit of shareholders and ceo’s running control frauds and at the expense of the company actually producing tangible goods spent into the economy.

Why put the unreal 10 person economy where there is no growth in dollars as one set – and then introduce another parameter of putting in another shot of money at interest – Do you suppose you ought to put another person in therre as well – also explain why buying baseball cards and gambling at a table produce extra money that those who don’t win at that table have to then borrow the ill gotten gains from that table to buy their inflated real estate that the very gambling table bid up to the hilt – explain why businesses buy back their own inflated stock from the gambling table so that their big shot ceos can stay at the table — gambling on the business dime.

A shame that these “leaders” talk about resillience yet make their own companies brittle – because thats how the gambling table is tax insentivised to play – them is the house rules defined by the tax system – change that and you will change the tilt in the table

Good article. But I think the way around a lot of the objections to debt relief the author itemizes would be a restructuring of the bankruptcy code. Return it to the code as it existed prior to 2005 with a couple of additional tweaks. The code that Biden (Senator MBNA) in large part was responsible for passing by the way. The changes to the BK code in 2005 resulted in large part with the student loan debt crisis we have today (the code did away with the allowable wiping out of student debt in BK). The tweak I would add would be the mortgage adjustments that the author advocates. Have the home appraised during the BK process and wipe out any debt owed above the value of the property (in the code prior to 2005 if you did a Chapter 7 you lost the home). The individual could keep their home but with no equity. This, along with being able to once again do a Chapter 7 to wipe out student debt, medical debt, and credit card debt would allow individuals to once again get a fresh start. No jubilee, no fancy programs required. And no appearance of give aways.

And no appearance of give aways. Jack

Why be shy about giving fiat to all citizens?

After all, SOME fiat creation is undoubtedly good and what better way, in addition to deficit spending for the general welfare, than an equal Citizen’s Dividend?

Moreover, we could increase the DEMAND for fiat by allowing everyone to use it in account form and by abolishing all other privileges for private bank deposits.

In order to get the politicians of either side to buy into such an idea, one would need the backing / understanding of Joe Public, and that ain’t going to happen anytime soon!

However, social capital that has been tokenised for contribution to local communities is something that everyone will be able to get behind.

It’s in development over here in the Uk and promises to give ordinary people the chance to earn such tokens into existence for contribution to the common good via their local community group and good cause.

All politicians will have to get behind the value of those tokens otherwise the public will not re-elect them.

Thanks for posting an excellent article.

I have written extensively on debt, both in this blog and in my own blog called NewLawsforAmerica.blogspot.com

As Richard Vague points out, getting rid of current debt is only part of the struggle. It is also necessary to reduce the need for debt in the future.

Part of this can be accomplished with better social insurance. If college and health care were fully funded by taxes, then a big chunk of consumer debt would go away. I know of no Germans or Norwegians who carry debt for college or health care.

Mortgages and business loans are not so easily resolved…..a combination of monetary reforms and streamlined bankruptcy laws is probably the answer.

My study of debt has left me with an appreciation of forced savings. It sort of like I started with AOC and wound up next to Dave Ramsey. If we do not force people to save in reasonable amounts for retirement, down payments, and emergencies, then eventually we are forced to collect taxes and bail them out. There is force used either way,

Fair enough — but remember that the forced savings represent demand destruction that must be offset (either by exports or deficits) lest the economy shrink.

What would a debt jubilee accomplish if the root is rotten? How could it portend to correct the imbalance through a mechanism just as twisted as the tax law? We will, I fear, keep squabbling over whose is whose and who deserves what until there is nothing left.

That is, unless money is seen as a tool and not as a possession. Why not make it simple? Debt grows the economy by increasing the number of transactions which requires an increase in money supply. This depends on the potential for growth of a market sector, where either too much or too little money causes stagnation. The basic idea behind relying on market forces is exactly that: we don’t know where the money needs to be, so we rely on supply and demand to estimate the value of money (ie if there is too much or too little money).

Why not have the sovereign (ie Congress or their appointee, such as FED, banks) issue interest free debt according to market need and state intent (ie policy, infrastructure, R&D). I mean all debt.

Naturally, there would be inflation in some areas and deflation in others, and this would be re-balanced through taxation. Simply, use a progressive tax that takes a huge percentage off the wealthiest and nothing from the poorest. This has nothing to do with fairness (ie wealthiest deserve the money and vice versa), and everything to do with leveling the money supply and countering inflation/deflation after the money has served it’s purpose. Thus, money would be something to use, easily accessible to all who have the ambition and vision, and not something to gain.

This would put onus on the government to allocate debt wisely and someone could favorably give more to others. I don’t think it is possible to remove corruption and fraud completely, but with a simple progressive tax with no exceptions, I imagine it would balance out nicely in the end.

I can dream at least….

To clarify: easy debt would counter deflation and theoretically make innovation accessible to all. Debt repayments and taxation would counter inflation over the long and short term, respectively.

If people don’t expect to get paid back, I suppose they would not lend money, so substantial private debt forgiveness ought to pretty much eliminate private lending. It is said this would harm “Growth” which the article assumes is an unalloyed good, even though we know it is destroying the habitable parts of the earth. On the other hand, sovereign debt doesn’t matter because you never have to pay it back. So, clearly, the solution, if you must get another hit of Growth, is to nationalize the banks, who would then be empowered to lend out that good government money without too much restraint. The borrowers would pay it back only if and as they struck it rich, or died with a positive bank balance — not because the gobmutt needed the money, but to keep down inflation. Private lending at interest would be illegal; those burdened by excess material possessions would just have to stuff their mattresses with their bonds, give the stuff away, or run up the prices of collectibles.

I think the Growth thing is a serious problem, though. You can’t just keep destroying stuff forever.

Michael Hudson made an important point in his recent essay. The Debt Jubilee rulers instituted that policy for social stability within their kingdoms.

We seem to be willing to accept the chaos and violence that comes with unrestrained debt serfdom.

The demonstrators who set up a mock guillotine in front of one of Jeff Bezos’ palaces knew what they were doing.

Chaos and violence takes the deserving and the undeserving indiscriminately.

Debt jubilees would also help restrain the

moral hazard of loansharking and usery.

Before fantasising about all kind of wonderful and unrealistic debt jubilee schemes, why not start tackling the rootcause of the problem first: Monetary policy is way too easy!

For example, massive amounts of private debt are being created to buy back shares. Of course this is what companies do when they can borrow at deeply negative real interest rates. But this does absolutely nothing for sustainable economic growth and only makes the system more vulnerable to shocks because of the high leverage. What you want is exactly the opposite of this: corporations should issue equity instead. Isn’t that the whole point of having a stockmarket?

Also, we should allow zombies to fail. That is painful in the short run, but weeding out the dead wood promotes innovation and growth in the long run.