Lambert here: Sounds like code bloat.

By Fernando Arteaga, Postdoctoral Fellow, Economics Department, University of Pennsylvania, Desiree Desierto, Affiliate Faculty, George Mason University, and Mark Koyama, Associate Professor in Economics, George Mason University. Originally published at VoxEU.

The Spanish Crown had a monopoly on the trade route between Manila and Mexico for more than 250 years. The ships that sailed this route were “the richest ships in all the oceans”, but much of the wealth sank at sea and remain undiscovered. This column uses a newly constructed dataset of all of the ships that travelled the route to show how monopoly rents that allowed widespread bribe-taking would have led to overloading and late ship departure, thereby increasing the probability of shipwreck. Not only were late and overloaded ships more likely to experience shipwrecks or to return to port, but the effect is stronger for galleons carrying more valuable, higher-rent cargo. This sheds new light on the costs of rent-seeking in European colonial empires.

In 2011 underwater archaeologists discovered the remains of the San José, a galleon sunk near Lubang Island, Philippines, in July 1694. It was one of 788 galleons that sailed between Manila and Acapulco, Mexico, between 1565 and 1815 as part of the Manila Galleon trade. The San José was laden with a huge amount of silks and spices, over 197,000 works of Chinese and Japanese porcelain, 47 chests full of objects of worked gold, and hundreds of other chests containing precious stones and objects, the total value of which was recorded as 7,694,742 pesos or more than $500 million in today’s money.

What does the sinking of the San José tell us about the costs of colonial trading regimes and the costs of corruption or rent-seeking more generally? This is a question that goes back to Adam Smith (1776).

From Tullock (1967) and Krueger (1974), we understand that the overall welfare costs of corruption can exceed the gains to the beneficiaries; from Shleifer and Vishny (1993), we know that the industrial structure of rent-seeking matters. We also have rigorous empirical studies of the costs of corruption in modern settings ranging from Indonesia (Olken and Barron 2009) and India (Niehaus and Sukhtankar 2013) to sub-Saharan Africa (Reinikka and Svensson 2004). But little empirical work has been done on colonial trading regimes.

In a recent paper (Arteaga et al. 2020), we examine the costs of corruption in the context of the Manila Galleon trade. The Manila Galleon trade was the longest, most profitable, and most celebrated colonial-era trade route. Importantly, the galleon trade was a government monopoly. The Spanish Crown owned the ships and restricted the number of voyages to one per year between Mexico and Manila; it also restricted the number of ships that could sail as part of each voyage. These restrictions made space on each galleon extremely valuable.

There was tremendous demand in Mexico and Spain for East Asian silks, textiles, porcelain, and lacquerware. Merchants from mainland Asia would arrive in Manila in May, bringing with them these highly valued goods, which they exchanged with Manila-based merchants for silver. These Manila merchants would then seek to load their cargo on galleons bound for Mexico. Space on each was rationed; officially, only individuals with tickets (boleta) were allowed to load their cargo. In practice, however, corruption was widespread, and merchants could bribe ship captains to carry additional cargo.

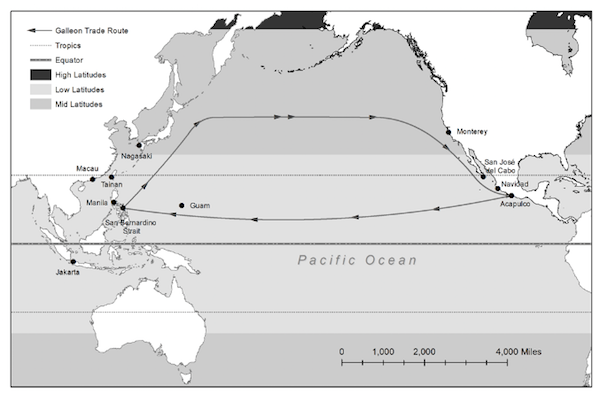

Figure 1 The route of the Manila Galleons

We formally model this process: traders in Manila, who want to sell merchandise in Acapulco, bribe galleon officials in exchange for cargo space. It takes time to load the cargo, but if the ship leaves too late it will run into perilous waters during the monsoon season.

The ship’s captain extracts the maximum amount of bribes. The logic behind this result is simple: as many merchants are vying for an allocation of the total space on the galleon, ship officials can extract maximum bribes by pitting each merchant against another to bid the bribe up to the cargo’s value.

Additionally, when the cargo value is very high, officials are induced to accept more cargo, even beyond the legal limit, and to delay departure past the deadline to load more cargo. That is, they would be willing to accept a larger probability of shipwreck as long as the marginal value of each cargo is greater than the increase in the probability of shipwreck. With more valuable cargo, merchants are more able to compensate officials for the expected cost of a shipwreck.

This model predicts that ships that depart late are more likely to be overloaded. We document this relationship empirically using a newly created dataset containing the universe of all ships that sailed between Manila and Mexico between 1565 and 1815.

We begin by establishing a robust relationship between sailing past the deadline from Manila and the probability of shipwreck (Figure 1). This relationship is not explained by storms or typhoons or other factors such as the experience of captains, and the age or type of ship. As a placebo, we show that there is no such relationship for the reverse voyage between Acapulco and Manila – there was no incentive to overload those ships as they mostly carried silver as payment for the traded goods.

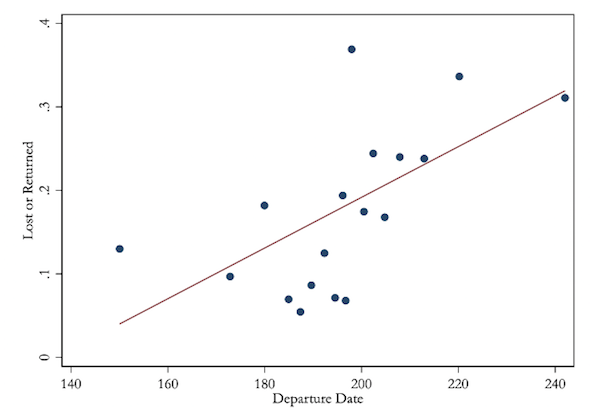

Figure 2 Relationship between departure data and a failed voyage, controlling for temperature, typhoons, and captain experience

Next, we rule out alternative factors that historians have linked to late departures including the arrival date of the ship from Mexico, the threat of pirates and ships of enemy powers, and the volume of merchants arriving from China. We find that none of these affects the positive relationship between a late departure and a failed voyage.

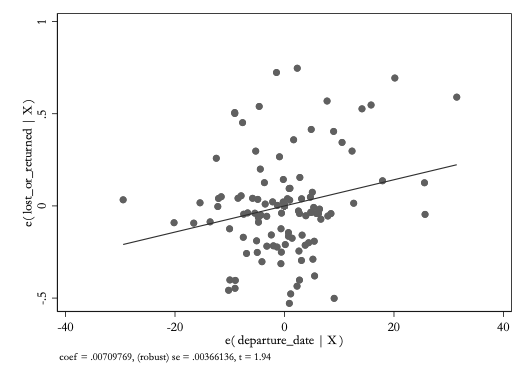

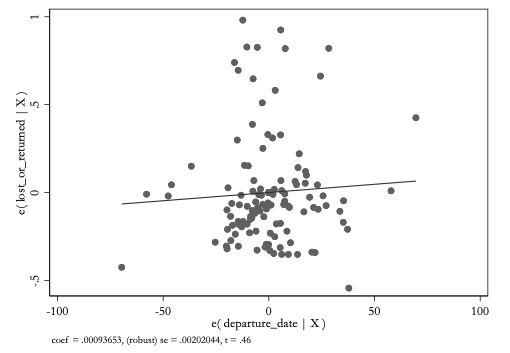

Finally, we take two additional predictions of the model to the data. First, the model predicts that ships with a smaller capacity are more likely to be severely overloaded when they sail late. Consistent with this, Figure 3 shows that the relationship between a late departure and a failed voyage was greater for smaller ships.

Figure 3 Relationship between late departure and failed voyage by low tonnage (top panel) and high tonnage (bottom panel)

In addition, when the value of the cargo is higher, we would expect late ships to be more overloaded as the bribes that merchants would be willing to pay would be higher.

To test this, we employ several proxies for the value of the cargo. First, we know that if a voyage did not take place in a given year for whatever reason, then in the following year there would be a lot of pent up demand for Asian products in Mexico and Spain. Consistent with this reasoning, we find evidence that the relationship between late departures and failed voyages was greater following a failed voyage.

Second, the demand for Asian goods would also likely be greater in years when the Mexican economy was booming. We find support for this, using silver output as a proxy for demand within the Mexican economy.

Third, we would also predict that when competition was introduced at the end of the 18th century, the value of cargo space aboard the Manila Galleons would fall and the relationship between late departures and shipwrecks would disappear. This is indeed what we find, once competition was introduced and the Manila-to-Mexico route ceased to be a government monopoly.

Together, these results provide additional evidence that is consistent with the mechanism outlined in our model. Ships in the Manila Galleon trade were more likely to be shipwrecked or to return to port because they were late and overloaded; in short, they were shipwrecked by rents.

This study demonstrates how monopoly regulations can have unanticipated negative consequences in the form of shipwrecks. While this historical setting is unique, the lessons from rent-seeking in the Manila Galleon trade can be generalised. The mechanisms responsible for shipwrecks in the Galleon trade are likely operative in other settings. For instance, cargo limits are often not observed on smaller flights – a problem that is particularly acute in developing countries – and this has been anecdotally linked to airline crashes.

How does free trade work anyway?

You want to get the cost of living down, so employers can pay internationally competitive wages.

The UK knew how to prepare for free trade in the 19th century because they used classical economics.

The US (and the West) didn’t know how to prepare for free trade in the 20th century because they used neoclassical economics.

How did the UK prepare to compete in a free trade world in the 19th century?

They had an empire to get in cheap raw materials; there were no regulations and no taxes on employees.

It was all about the cost of living, and they needed to get that down so they could pay internationally competitive wages.

UK labour would cost the same as labour anywhere else in the world.

Disposable income = wages – (taxes + the cost of living)

Employees get their money from wages and the employers pay the cost of living through wages, reducing profit.

Ricardo supported the Repeal of the Corn Laws to get the price of bread down.

They housed workers in slums to get housing costs down.

Employers could then pay internationally competitive wages and were ready to compete in a free trade world.

That’s the idea.

The interests of the rentiers and capitalists are always opposed with free trade.

The Repeal of the Corn Laws caused conflict between the old, landowning class and the new capitalist class.

This almost tore the Tory Party apart in the 19th century.

See where neoclassical economists go wrong?

Everyone pays their own way.

Employees get their money from wages.

The employer pays the way for all their employees in wages.

Off-shore from the US, ASAP.

This is missing.

Employees get their money from wages and the employers pay the cost of living through wages, reducing profit.

You can pay wages elsewhere that people couldn’t live on in the US.

You need to off-shore to maximise profit.

Everyone that uses neoclassical economics trips up over the “cost of living” including the Chinese.

Disposable income = wages – (taxes + the cost of living)

Taxes and the cost of living sum together in the same brackets, so it shouldn’t be hard, but today’s policymakers don’t have the equation.

The Chinese have been trying to increase consumption, but they were using neoclassical economics.

Davos 2019 – The Chinese have now realised high housing costs eat into consumer spending and they wanted to increase internal consumption.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MNBcIFu-_V0

They let real estate rip and have now realised why that wasn’t a good idea.

They had to learn the hard way.

The equation makes it so easy.

Disposable income = wages – (taxes + the cost of living)

The cost of living term goes up.

The disposable income term goes down.

They didn’t have the equation, they used neoclassical economics.

The Chinese had to learn the hard way and it took years.

What are those yellow vests doing on the streets of France, Macron?

The “cost of living” trips everyone up that uses neoclassical economics.

See post below…all that is going on in the global economy since it has been global is more of satisfying the “frantic urgency of debts”….with all the vileness that brings out in humanity.

What was the normal percentage of voyages ending in sinking in those days? Big ships? Smaller ships?

How good is the data for temperature and typhoons in for the first 100 years or so of the voyages?

Fascinating study this. I believe that ships in this era also had spare timbers aboard in order to make running repairs in case of storms and the like. I wonder if some of those captains got rid of this ‘insurance’ in order to make more room for cargo. Those Manila Galleons also had to be armed in case of pirates so I wonder if a few captains removed the weight of some of those cannon for trade goods as well. These captains bet their lives a well as the lives of their crews if they were too corrupt and it sounds like some of them lost that bet. But I guess that if you made a successful round trip, that you would be set for life.

Future gold mines in 100,000 years will be where sunk buillion vessels have folded into the geology…

Yes, and apply this to today’s waste stream.

Fortunes being made by “mining” twentieth century landfills is a plot item in some science fiction. If I remember correctly, Gibson mentions the idea.

The other extreme of this is in Philip Wylie’s “The End of the Dream.”

I’ve always thought that if stuff couldn’t be profitably recycled it at least be sorted in a landfill. It would make the eventual landfill mining more efficient.

Glad to see that someone else has read Philip Wylie’s “The End of the Dream.” I think that it is mostly forgotten these days.

I have a good friend that has been a dreamer most of his life. He found some other “like minded” people and went to search for a shipwreck in the gulf of Mexico. They found it with the help of a relatively new technology at the time, a Magnetometer. Lots of gold objects and other pricey stuff. The state of Texas seized most of it and said it’s ours. The state of Florida laid claim to the rest. He now runs charters in the Caribbean. Apparently “get rich quick” isn’t the answer either. We laugh about it from time to time. He finds very little humor in it.

I am struck by a GMU economist actually acknowledging that monopoly rents can have a societal cost…

Was she denied tenure?

Alot of that treasure was to help indebted Kings who racked up debt like early Trumps.

The entire rape of the “new world” was engulfed in the “frantic urgency of debts” by all of those involved from the Kings to the conquistadors to the sailors to the colonisers.

That is how it is put in David Greaber’s “Debt: The First 5000 years.”

Snippets from the chapter “The Age of the Great Capitalist Empires”:

“….Cortes had his victory. After eight months of grueling house-to-house warfare and the death of perhaps a hundred thousand Aztecs, Tenochtitlan, one of the greatest cities of the world, lay entirely destroyed. The imperial treasury was secured, and the time had come, then, for it to be divided in shares amongst the surviving soldiers.

Yet according to Diaz (Note: Diaz del Castillo accompanied Cortes), the result among the men was outrage. The officers connived to sequester most of the gold, and when the final tally was announced, the troops learned they would be receiving only fifty to eighty pesos each. What’s more, the better part of their shares was immediately seized again by the officers in the capacity of creditors – since Cortes had insisted that the men be billed for any replacement equipment and medical care they had received during the siege. Most found they had actually lost money on the deal….”

…These were the men who ended up in control of the provinces and who established local administration, taxes, and labor regimes. Which makes it easier to understand the descriptions of Indians with their faces covered by names like so many counter-endorsed checks, or the mines surrounded by miles of rotting corpses. We are not dealing with a psychology of cold, calculating greed, but of a much more complicated mix of shame and righteous indignation, and of the FRANTIC URGENCY OF DEBTS that would only compound and accumulate…..

Graeber goes on to describe Cortes, who always managed to find himself in more debt despite all the theft.

…Cortes’s angry foot soldiers when unleashed on the Aztec provinces, embody something essential about the psychology of debt….the frantic urgency of having to convert everything around oneself into money, and rage and indignation at having been reduced to the sort of person who would do so.”

“Midas disease”… a bigger epidemic than any coronavirus.

More like “shipwrecked by debts” that all involved in that great theft ,from the Kings on down, struggled to pay.

Great piece, many thanks for reposting. I find this period of history utterly fascinating.

The Ayala Museum and the Museum of the Philippine People are both must-sees for anyone visiting Manila who is interested in this topic.

One point this excellent piece doesn’t touch on much: the Manila galleon monopoly was itself a workaround to severe restrictions on trade imposed by the Chinese Ming and Qing authorities from the late 1400s onwards. Even before da Gama rounded the Cape, the wealth the spice trade via Malacca and India brought in to southern China, (whose peoples put commerce ahead of loyalty to the Mandate of Heaven) had proved destabilizing. That and the drain of fighting the Manchu along the northern frontiers was why the Ming scrapped the treasure fleets.

The Portuguese and Spaniards were able to win concessions though as they could pay in the silver specie the late Ming needed to fund growth, especially their big infra buildouts (canals, roads, etc.) of the 1500s.

However, trade still got cut off periodically, at times because missionaries became disruptive, but mainly due to the civil wars, plagues and disorders as the Ming fell to the Manchu Qing. Ming refugees broadly known as ‘Hakka’ flocked into southern ports, and overseas, and established themselves in trade. The Qing armies savagely depopulated the Fujian coasts for decades at a time to shut off their funding.

Meanwhile, demand for ‘Chinoiserie’ among the mercantile middle classes of Europe blew through the roof starting in the early 1600s, eclipsing the spice trade. To this day, wedding china is the traditional badge of membership in the Western bourgeoisie. Soaring demand redoubled incentives on all parties to evade or just break the restrictions, especially as shipbuilding and navigation technology continued to improve.

Manila had a large Chinese trader population, well predating the Spaniards, and was a very easy sail for traders/smugglers out of the Chinese coastal ports above Canton (Amoy, Foochow, Wenchow, etc.). So Chinoiserie tended to accumulate there even when the embargos were strict. Of course, by the mid 1700s there were plenty of other outlets and the Manila galleon faded into obscurity.

Anyway, fascinating period of globalization, and not reducible to a just so story of ugly white men with guns, germs and opium (although there was plenty of that, sure).