Yves here. Richard Vague describes how exports and manufacturing prowess have long depended on considerable government support for basic research. If the US wants to tame its trade deficit, more Federal funding of foundational R&D is a win-win, because it will also create higher-skilled, well-paid jobs. But the US is allergic to having an industrial policy, even though we have one by default via particular sectors getting lavish tax breaks, subsidies, and direct spending, such as real estate, arms-makers, Big Finance, and health care.

By Richard Vague, Acting Secretary of Banking and Securities, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and Chair, The Governor’s Woods Foundation. Originally published at Democracy: A Journal of Ideas; cross posted from the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

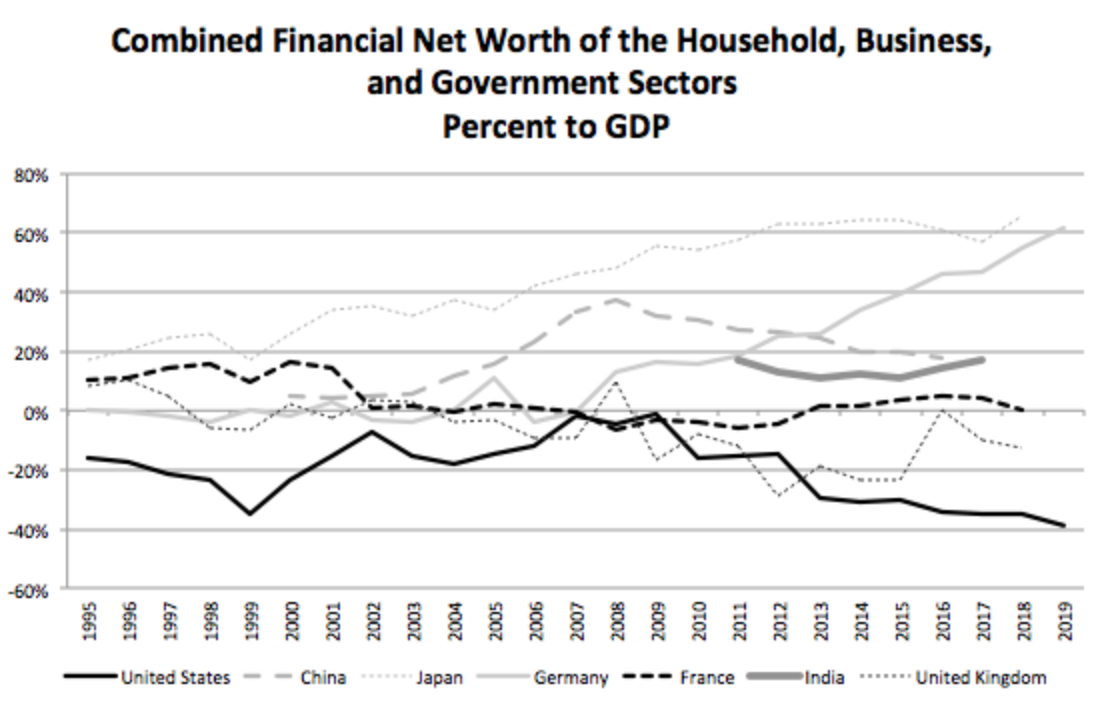

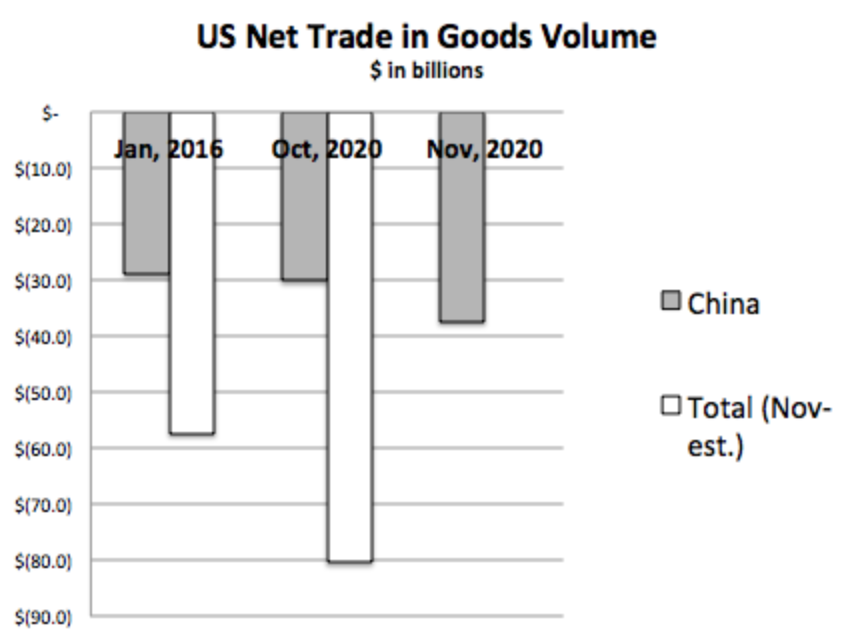

The United States currently has a problematic trade deficit, not only with China but globally. U.S. imports exceeded its exports by $80.4 billion in October of this year alone. This trade deficit increases the debt burden of U.S. households and businesses; depletes our country’s financial capital (See Chart 1); contributes to rising inequality; and makes wage growth all the more difficult.

At least in his concern about the trade deficit with China, Donald Trump was on to something. Yet his confrontational and clumsy approach to this problem resulted in nothing but lost ground. Our trade deficit with China did not improve during his presidency, and our trade deficit with the world grew significantly worse (See Chart 2)

Trump failed on trade because he relied exclusively on tariffs, which are a fickle tool in a world where currencies float, trade retaliation by other countries comes quickly, and supply chains are complex. While tariffs have their place, and have been part of U.S. trade history, they are only one small part of a bigger equation.

So if Trump’s tariffs didn’t work, how can we improve our balance of trade?

The answer is obvious but so widely overlooked that it might sound like heresy: To improve our balance of trade, we should make better and more advanced products and services. That has been our advantage for 150 years—so much so that our product and service superiority is almost taken as a given. Don’t we export the best products and services in the world?

A country’s exports can be measured by their complexity, which is a way to gauge this aspect of trade. In today’s world, complex products include such items as high-end medical and surgical devices, robots, specialized industrial equipment, high-end computers and telecommunications equipment, and genetically engineered biological materials. The Observatory of Economic Complexity, originally founded by MIT, publishes an index called the Export Complexity Index (ECI) which does this very thing. Not surprisingly, the perennial export powerhouses—Japan, South Korea, and Germany—rate among the highest on the ECI index with recent ratings of 2.39, 1.97, and 1.95 respectively, and, for each, these indexes are rising. Their respective average export surpluses over the last 20 years as a percent of GDP have been 0.5 percent, 3.2 percent, and 5.4 percent.

The United States ranks 13th among the world’s countries, with an index of 1.44, a decline from an index of 1.54 in 2011. China is 20th at 1.18, but its index has been rising crisply from the 1.01 it registered in 2011. The U.S. average net export surplus has been negative 3.8 percent over the last 20 years, while China’s is a positive 3.4 percent. China is now the country with increasingly more complex exports as compared to the United States.

One group of researchers affiliated with University of California at Berkeley, MIT, and other major universities took this analysis a step further. They adjusted the ECI to account for the difficulty of exporting each product and the volume of a given country’s exports in order to create an index they call the ECI+. This index takes into account that the harder it is to export a product—for example, a large aircraft—the greater the competitive advantage of existing exporters, due to the difficulties faced by new entrants hoping to compete. By this index, China is first in the world and rising and the United States is fourth and trending downward.

This trend matters immensely, since globally the most complex and advanced products are most likely to command price premiums and attract very high demand. And this complexity is now found across an ever-broader range of products since today even cars and household appliances are computers. In health care, an increasingly dominant economic category, products offered for export are becoming exponentially more complex, and include manufactured biological and genetically reengineered materials.

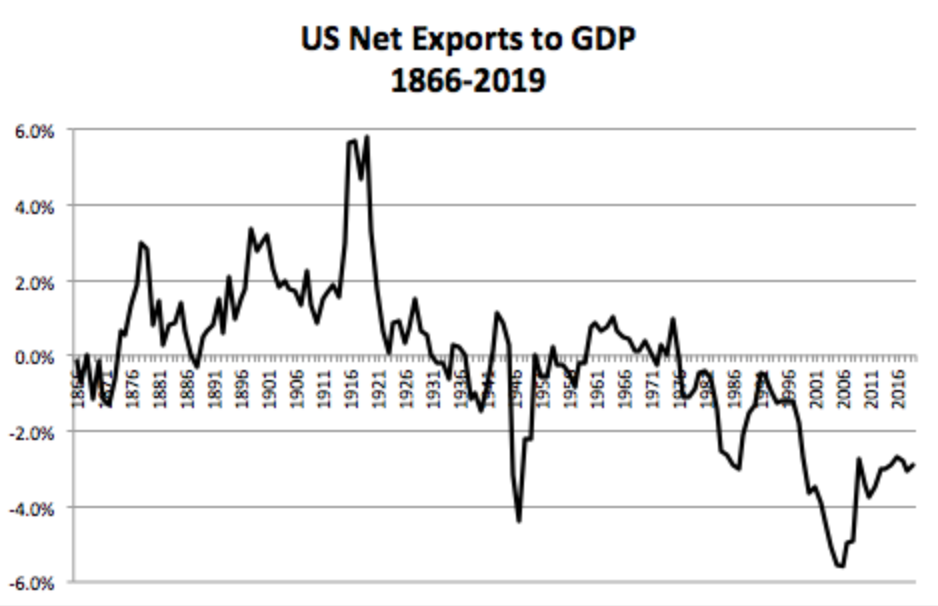

Chart 3 shows the U.S. net export position from after the Civil War to the present. It was good, even robust, until roughly 1981, and has been largely negative since then. Keep in mind that this is both goods and services, so the rationale that our trade position has changed because we have shifted to services doesn’t hold up because the services we export are included in the calculation.

At a very fundamental level, trade is a measure of the relative net demand for our products and services, and therefore a measure of the desirability and appeal of those products and services. This more fundamental aspect of the issue seems to have been lost in the obsession with tariffs. The higher the appeal and demand for a given product or service, the more power the company offering it has to command high prices, a factor sometimes referred to as “pricing power.”

One more thing: The more pricing power a company has, the greater its capacity to pay higher wages. The more advanced a product is, the greater the skill required to make that product, and higher wages follow higher skill levels. Thus, if we are seeking higher U.S. wages, then more advanced products and services can be a meaningful part (although far from the only part) of the solution.

Here’s the catch. The most advanced products and services come largely from intensive, long-term, foundational, and basic research, the kind that most companies cannot afford to undertake because the payback is so often measured not in months or years but in decades. This would include research in artificial intelligence, 5G and 6G communications networks, biotech and genetic engineering, electric vehicles and batteries, supercomputing, quantum encryption, and high-tech manufacturing. The research needed in these areas is far deeper and more expansive than what private-sector companies currently undertake. It most often comes from government support of academic research in the most advanced laboratories and with the most extraordinarily cutting-edge research and engineering.

But U.S. government funding for research and development (R&D) has been declining as a percent of our national income for more than 50 years. From 1964 to 2018, total federal funding of R&D has dropped by nearly two-thirds relative to GDP, from 1.83 percent to 0.66 percent. Trump showed no interest in reversing this U.S. decline. Meanwhile, in the past ten years, China’s central government funding for science and technology has tripled in real yuan.

It’s stunning. Since 2000, the U.S.’s “R&D intensity”—its expenditure on R&D not only by the government but also by academia and industry as a percentage of GDP—has been fairly flat, and currently stands at 2.8 percent. That’s slightly above the world average, but well below Israel’s 4.9 and South Korea’s 4.5 percent. In that same period, China’s R&D intensity has more than doubled, from 0.9 percent to 2.1 percent. So we still lead China here, but China has passed the EU in R&D spending, and its brisk growth in this area is projected to continue, while ours is at risk of remaining static.

The gradual abdication of our global research leadership has occurred at the very time that China has been deliberately pouring funds into the most advanced technologies. China has made clear its national goal of becoming the dominant global, high-tech manufacturer by 2025, an international leader in innovation by 2030, and a world powerhouse of scientific and technological innovation by 2050.

This research and innovation gap is much more the story of our trade deficit than the lack of high tariffs.

Yet the raw facts of this story are unknown to most, and of little concern to others who do know them. In fact, some believe that it is not the place of government to provide research and development funding. Some insist the marketplace should be the sole source of business funding, including R&D funding, and that the government should not subsidize industries, products, companies, or markets; in other words, the government should not be in the business of “picking winners.”

But that belief reveals a troubling ignorance of American business history. The U.S. government has been actively supporting business advancement from its earliest days, starting with its support and guidance of the colonies’ meagre manufacturing capabilities to help them build weapons for the American Revolution. This was quickly followed by Alexander Hamilton’s 1791 Report on the Subject of Manufactures and the establishment of the accompanying state-sponsored, tax-advantaged Society for the Establishment of Useful Manufactures, in Paterson, N.J. The Report on Manufactures was an overt call by Hamilton for the United States to fully join the Industrial Revolution, certainly the most profound business revolution in world history.

The most consequential U.S. economic development of the early 1800s was the state-funded Erie Canal. That was followed by decades of government support and subsidies for railroads, the most important industry of the nineteenth century, including land grants and other support for the Illinois Central Railroad and the Transcontinental Railroad. This support often came after purely private efforts had failed.

In 1832, Abraham Lincoln first entered politics by championing government support for internal improvements that were almost entirely intended to improve trade and commerce. After he became established as a lawyer, Lincoln’s best-paying client was the Illinois Central.

Another crucial nineteenth-century development was the telegraph, and Samuel F.B. Morse’s test telegraph line between Washington and Baltimore was funded by a $30,000 grant from Congress. He gave a high-profile initial demonstration of this new technology in 1844.

In the 1870s, Congress allocated funds to form the National Board of Health, with the initial goal of investigating the causes of epidemic diseases such as cholera and yellow fever. That led to today’s National Institutes of Health (NIH), whose support by the government has been responsible for a vast number of recent pharmaceutical breakthroughs.

In 1940, Vannevar Bush, founder of Raytheon and former dean of MIT’s School of Engineering, proposed an idea to President Roosevelt for a new federal agency to help coordinate scientific research with military relevance. That proved so successful in the war effort that it inspired the creation of the National Science Foundation (NSF) in 1950, which has been an ongoing boon to business innovation ever since.

The Manhattan Project to develop an atomic bomb during World War II led to hundreds of innovations subsequently commercialized by U.S. businesses. The massive expenditures in the space and arms races with the Soviet Union financed and boosted innovation on the microchip and many other technologies. The government’s support of microchips for missiles and space exploration alone reduced the price of a single chip from $32 in 1961 to $1.25 just ten years later, making computers affordable for the masses.

The Soviet Union’s successful launch of the satellite Sputnik in 1957 spurred the passage of the Small Business Investment Act in 1958. The small business investment companies (SBICs) created by that Act provided the funding that constituted three-quarters of venture capital between 1959 and 1963 and jump-started the modern venture capital industry. SBIC funds helped meet the early capital needs of companies such as FedEx, Tesla, Apple, and Intel.

The iPhone, perhaps the most iconic, consequential artifact in the world today, was built on technologies that emerged directly out of, or were significantly enhanced by, many large-scale government research efforts. This list includes the invention of the Internet itself; microprocessors and central processing units; dynamic random-access memory; micro hard drive storage or hard drive disks; liquid-crystal displays; lithium-polymer and lithium-ion batteries; digital signal processing; the Hypertext Transfer Protocol and Hypertext Markup Language; cellular technology and networks; click-wheel navigation and multi-touch screens; and artificial intelligence, with voice-user interface.

These examples are just one small part of the story, and they underscore that for many of the most important economic developments in our nation’s history, it wasn’t the marketplace that determined success, but the government in concert with the marketplace. Huge swaths of American business success have been built on government-funded R&D. This investment has been central to the United States’s rise to global preeminence.

This history and the current R&D gap between the United States and other developed countries speak to our ongoing need for an overt industrial policy that focuses government-funded research on areas that will bring robust growth. The amounts required to restore a more robust effort here are not overwhelming in relation to the government’s overall budget of $4.5 trillion. A 10 percent increase in our federal R&D spending would total a mere 0.35 percent of that budget. A doubling would total 3 percent of that budget and would supercharge and completely revolutionize our economy within a generation, bringing a flood of higher-paying jobs.

Yet even with this renewed investment and industrial policy, we will not capture the full benefit of our innovations unless we also commit to the research and development necessary to manufacture these new and advanced products in the United States. If we develop a spectacular new product but don’t manufacture some or most of its components in the United States after it is commercialized, then we will have won only half the battle.

Our manufacturing prowess, good as it still is, has slipped in relation to advanced manufacturing in other parts of the world.

Years ago, when products were simpler, all the crucial intellectual property and intellectual capital resided in product development and design, and assembly and manufacturing could be sent offshore to lower-wage countries without ceding any of that intellectual capital. Manufacturing was straightforward and could easily be re-shored if needed, or so we thought. With that, business leaders and policymakers concluded that there was little intellectual capital to be lost by offshoring manufacturing.

Today, the complexity of products means that there is almost as much intellectual capital and intellectual property in the manufacturing process itself as in product development. Thus, for an increasing number of products developed in the United States but manufactured elsewhere, even without consideration of wage differences, there is simply not the option to re-shore because the intellectual capital and manufacturing skills needed to manufacture it here have atrophied or been lost. For increasingly complex products such as high-end computing and telecommunications equipment, manufacturing is a form of intellectual capital unto itself.

But there is hope. Advancements in manufacturing automation, both actual and possible, now mean that the labor component of product cost is declining and thus the significance of labor cost differences are disappearing. With that, re-shoring has become increasingly feasible.

These are jobs that have long since been lost to other countries because this manufacturing has been moved wholesale and in its entirety to these other countries. Greater automation of the process means that this manufacturing can be moved back to the United States. The people hired to work in these now re-shored plants will be net new jobs for the United States. And they will be higher skilled, higher paying jobs—both the front-line jobs and, more importantly, the engineering, design, and administrative jobs to run these re-shored plants. Overall, U.S. job growth will accelerate.

Yet, since so much U.S. manufacturing knowledge has been lost, much of that prowess will have to be developed anew, which will take years and involve significant new manufacturing design, tooling, and training costs to create the more highly automated manufacturing design to make reshoring economically feasible—costs that many companies simply can’t afford.

For example, a small electronics firm that I know has all its manufacturing done in China because it is two-thirds less expensive to do it there than in the United States. That’s assuming a U.S. manufacturer could even be found with the technical ability to handle the job. However, this firm has now applied for a Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grant sponsored by the NSF for the purpose of creating a more automated and streamlined manufacturing process that could make re-shoring possible. If it receives that grant, it can afford the engineering changes that would both streamline the design—e.g., the use of fewer and less expensive materials, and simpler or fewer parts—and greater automation in product assembly. This company couldn’t afford to engineer these design changes otherwise. But with those changes, it will become feasible to manufacture that product in the United States at a cost much more comparable to its offshore manufacturing cost.

Yet SBIR budgets aren’t nearly large enough to accomplish the re-shoring revolution we could hope for. An added investment as small as 1/10th of 1 percent of the budget could bring a profound change here and provide a very happy ending to the story.

At the very least, more automated manufacturing processes would make this type of manufacturing more “portable”—more easily moved from China to another country; if not the United States, then Vietnam, Singapore, or elsewhere.

Here’s another example—a breathtaking example of truly twenty-first-century manufacturing. At the University of Pennsylvania, scientist Carl June and his team of researchers, whose work I have supported, have pioneered what is effectively a cure for certain types of cancer, including acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

The procedure for this treatment involves taking out a select number of a patient’s T cells and then genetically reengineering and reprogramming the DNA in those cells to attack and destroy the cancer tumors. In most cases, once these modified cells are reintroduced into the patient’s body, that patient is cancer free in a matter of days—an almost miraculous result.

The process for genetically reengineering those cells is quite simply a manufacturing process, complete with an assembly line, albeit one that operates near a temperature of absolute zero. Manufacturing facilities staffed with well-paid technicians and scientists have been built in Pennsylvania for this purpose. If Pennsylvania continues to invest in this type of genetic engineering research, it can reclaim the preeminent role in manufacturing that it held over a century ago, led by the most cutting-edge manufacturing in the world.

We want and need this type of manufacturing to remain on our shores. It too will result in many new, high-wage U.S. jobs.

Increasing government funding of basic research could supercharge America’s product development and advancement. With that, we could regain and solidify our leadership in the most impactful new areas of opportunity—the areas mentioned above that include artificial intelligence, 5G and 6G communications networks, biotech and genetic engineering, electric vehicles and batteries, supercomputing, quantum encryption, and high-tech manufacturing. With better, more advanced products would come an improved balance of trade, more capital accumulation, and even a much-needed platform for higher wages.

A brief technical aside: Many of my economist friends tell me that since the dollar is the world’s reserve currency, and thus other countries are compelled to hold dollars, some level of current account deficit, of which the trade deficit is the biggest part, is inevitable. I’m not entirely convinced this is true, especially since the United States had a current account surplus for much of the 1960s and ’70s, a period in which we were already the world’s reserve currency. But even if I concede the point, it is still a matter of degrees. I frankly wouldn’t mind a current account deficit of less than 1 percent, as compared to the 2 to 3 percent where it currently stands.

So let’s help tackle the trade problem the right way—the powerful way—by increasing America’s investment in core and basic research and development.

Congrats! Have been daily reader since Lehmann collapse. Very educative and entertaining. Comments are gold.

The UK knew how to prepare for free trade in the 19th century because they used classical economics.

The West didn’t know how to prepare for free trade in the 20th century because they used neoclassical economics.

How did the UK prepare to compete in a free trade world in the 19th century?

They had an empire to get in cheap raw materials; there were no regulations and no taxes on employees.

It was all about the cost of living, and they needed to get that down so they could pay internationally competitive wages.

UK labour would cost the same as labour anywhere else in the world.

Disposable income = wages – (taxes + the cost of living)

Employees get their money from wages and the employers pay the cost of living through wages, reducing profit.

Ricardo supported the Repeal of the Corn Laws to get the price of bread down.

They housed workers in slums to get housing costs down.

Employers could then pay internationally competitive wages and were ready to compete in a free trade world.

That’s the idea.

The interests of the rentiers and capitalists are opposed with free trade.

The Repeal of the Corn Laws caused conflict between the old, landowning class and the new capitalist class.

This almost tore the Tory Party apart in the 19th century.

See where neoclassical economists go wrong?

Everyone pays their own way.

Employees get their money from wages.

The employer pays the way for all their employees in wages.

Off-shore from the West, ASAP.

This is missing.

Employees get their money from wages and the employers pay the cost of living through wages, reducing profit.

You can pay wages elsewhere that people couldn’t live on in the West.

You need to off-shore to maximise profit.

One way to reduce foreign* demand for US dollars is to stop issuing its inherently risk-free sovereign debt, including bank reserves, at non-negative yields/interest since these constitute welfare proportion to account balance, not according to need.

Should this seem balmy to some, I note that the MMT School already recommends a permanent Zero Interest Rate Policy wrt the inherently risk-free debt of monetary sovereigns, though this does not go far enough** from an ethical perspective.

That said, individual citizens should be shielded from negative interest to a reasonable limit via accounts of their own at the Central Bank.

* Another way to reduce foreign demand for US dollars is to prohibit foreign ownership of US land.

** Because of overhead costs and because shorter maturities should cost more (more negative interest).

tl;dr. I started reading the article, but after a few paragraphs I decided he’s treating the international trade problem like a family budget, and quit. I am not an economist, but my Intro Econ course was back in 1960, I loved John Kenneth Galbraith’s writing, and am strongly influenced by Jamie Galbraith’s The Predator State. There is also a great little book titled Paper Money, by George W. Goodman writing as Adam Smith back in 1981.

The problem is the same as the one MMT addresses. Government can’t collect taxes until they give their citizens money to pay the taxes. After that, government must continue providing enough money for the economy to operate. There is no way around it. The “public debt” is the national wealth, and if you try to reduce the debt you are destroying wealth and the economy crashes. In the same way, if your currency is the international reserve currency, and especially if it has become the replacement for gold, then the world economy depends on you continuing to provide enough of your currency. The only way for other countries to get dollars is to sell us stuff. If we don’t run a trade deficit, they won’t have enough dollars to buy our stuff and also won’t have enough dollars to buy each others’ stuff. If we somehow ended our current account trade deficit, the world economy would crash, bringing us down with it.

Once again, I am not an economist, and maybe I’ve been misled by shallow reasoning or misunderstanding what smarter people actually said, but it seems pretty clear to me once it’s been pointed out.

Fabulous Procopius. Agreed ;-)

If you must create money, do it into the hands of poorest.

A rising tide floats the matchstick before the boat.

If you must create money, do it into the hands of poorest. Lee

SOME fiat creation is an ethical necessity lest, for example, the old loot the young via a money system that does not keep up with population growth.

But yes, fiat creation beyond that created via deficit spending for the general welfare should be via an equal Citizen’s Dividend.

At the end, Vague did say he was OK with running a deficit, just a smaller one than now. Trade deficit = exporting jobs.

The perennial trade deficit…the price we pay for exorbitant privilege. If we ever began running large trade surpluses there would be a world-wide clamor for Bretton Woods II.

What if we were to run trade breakevens? Neither trade deficit nor trade surplus?

Trade defect -> Global Hegemony via Currency Controls, because the world is awash with US Dollars.

To be the reserve currency appears to require a trade deficit to get the currency “out there.”

That provides the US with a sanctions weapon.

Also not an economist but I think you are mixing up trade deficits and budget deficits.

I had a similar initial reaction, but questions of trade-deficit tolerance seem beside the point when we can look at the rising level of skills subjected to off-shoring, and the resultant loss of domestic technical capacity, and juxtapose that with the levels or raw materials exports to recognize that the US is becoming an extraction-based economy producing the materials for industrialized nations to process and sell back to us. The tables have turned. Reclaiming some capacity for innovation and production seems like an obvious benefit for the nation, if not for its oligarch owners.

This. I don’t share Vague’s concerns about the trade deficit itself, but it has led him to a concern I do share — the industrial capacity deficit. His solution also strikes me as correct: increased federal investment in R&D and a return to frank industrial policy.

I have to give Mazzucato credit for her work on this issue.

The “Exhorbitant Privilege” is as the heart of it. We have replaced gold with the US dollar as the international currency of choice. This means that we ship dollars overseas and get things back.

If you had a printing press for dollars, would you bother working? Would you bother making things for export? Heck no! There’s the problem.

Vague is very familiar with MMT. Your assumption is incorrect.

He left out a famous and important source of innovation – Bell Labs. It was a state sponsored/mandated system, and a product of industrial policy.

Speaking of telecom, Huawei’s dominance came about from being a state champion, as well as non-tariff trade barriers in its home market. Meanwhile, its main competitors were busy consolidating and cutting costs to improve gross margins as Western service providers squeezed them to please shareholders, fund vanity acquisitions, and do financial engineering as opposed to telecom engineering.

You got that right. A lot of companies cut their research & development budget as well as the staff and used it to pay shareholders. Maybe too these days using that money in stock buybacks to boost prices which leads to management bonuses. That is their seeds that they are scraping.

This is an excellent, excellent comment!

People don’t know how much of our modern world came from Bell Labs, but it covers everything from inventing the transistor (the basis of ALL modern electronics) to learning the age of the universe:

Bell Labs https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bell_Labs

And it also is an example of the current American Industrial Policy, It’s been sold to a foreign company.

I once long ago worked for a subsidiary of Bell Labs.

The above article is based on ignorance of economics.

The “trade deficit” merely means we send more dollars overseas than we receive. But, because the U.S. government is Monetarily Sovereign, it has infinite dollars.

Therefore, the so-called “deficit” is not a problem at all.

We send dollars, which we create infinitely at no cost by the touch of a computer key, and in return, we scarce and receive valuable goods and services which are created at the cost of human labor and physical assets.

In short, our trade “deficit” is the greatest deal we could have. The more, the better.

No, the US ran trade deficits in the Clinton era when the US was running fiscal surpluses, for instance. The reason the economy didn’t contract was that households levered up (HH savings plunged to zero and even negative) and we stoked a housing bubble.

Trade deficits = exporting jobs. If the US runs smaller deficits, then it does not need to run fiscal deficits to get to full employment:

https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2019/4/16/18251646/modern-monetary-theory-new-moment-explained

As pointed out above, running a trade deficit is necessary to maintaining our status as the reserve currency, but the US does not need to do that if we are more of an autarky (which we could be) or alternatively, we don’t need to run trade deficits as large as we do now.

Thanks for your comments.

Dollars flowing in and out of the country are “independent of monetary policy and net fiscal spending??” Hmmm . . . Depends what you mean by “independent of.”

The fact that the US. ran trade deficits while the Clinton government ran surpluses merely says that the private sector was being starved by a dumb government policy: Running a federal surplus.

So, predictably, we had a recession, which we always have when the government runs a surplus. (We were lucky. Most surpluses result in depressions. We “only” had a recession.)

When we run a trade deficit while the federal government runs a deficit, money flows from the government through the private sector to the foreign sector.

In essence, the government is using its infinite funds to acquire valuable goods and services for the nation — the more, the better.

As for exporting jobs, the goal is not work.

The proper goal of a government is not to make the populace labor. The proper goal is to make the populace prosperous.

That could be accomplished via the Ten Steps to Prosperity

Bottom line. The federal government never can run short of dollars. It has infinite dollars. It can provide infinite dollars to the people.

(Now, shall we discuss the facts that federal deficit spending is not “socialism” and it never causes inflation?”)

Perhaps the USA government can run out of dollars that foreign nations and producers actually want?

The USA has been the go-to reserve currency nation since 1944.

From Wikipedia

“The United Kingdom’s pound sterling was the primary reserve currency of much of the world in the 19th century and first half of the 20th century. However, by the end of the 20th century, the United States dollar had become the world’s dominant reserve currency.”

The outlook that the USA can forever create more dollars and always be able to convert them to the world’s scarce resources may be shown as “inoperative” (hat tip to Ron Ziegler) in the future.

If the USA no longer manufacturers goods, has inefficient health care and financial systems, no longer has natural resources to sell, no longer does much R&D and THEN loses reserve currency status (like mother England) the almighty US dollar could lose much value.

A “reserve” currency is a currency banks hold in reserve to aid international trade. Primary reserve currencies are the U.S. dollar, the euro, the British pound, and the Chinese yuan — the Japanese yen, to a lesser degree.

All the nations in the world somehow survive without owning the most popular reserve currency. The U.S. would, too.

Yes, IF “the USA no longer manufacturers goods, has inefficient health care and financial systems, no longer has natural resources to sell, and no longer does much R&D” the dollar could lose value.

None of those extreme and unlikely examples has anything to do with the reality that the U.S. does not benefit from having a positive balance of trade “(Positive” meaning it receives more precious goods and services, and sends out costless dollars).

If you owned a legal money-printing press, and you could print all the dollars you wanted in exchange for precious goods and services, would you rather receive more dollars and ship away more goods and services?

If the act of creating more dollars to buy precious goods causes the USA to hollow out manufacturing and R&D and lose the ability to design and make goods in the future, then I would rather ship away more goods and services.

It is keeping some skin in the manufacturing game.

If the USA were printing dollars and using them to equip USA factories and research labs and buy up scarce world commodities (tantalum, rare earth metals), then the exchanging of dollars for real goods could be quite a good deal for the USA.

But the apparent malaise in the USA indicates, to me, that this is not occurring..

The problem with this aspect of MMT is the underlying issue of “producing” paper vs producing goods. As you state, we can produce paper at no cost, which is used to buy goods created by human labor and real capital. What a trade deficit does is shift jobs from the deficit to the surplus country–China gets our manufacturing jobs, and we get some back in the form of trucking and cashiers at Walmart.

Most of the “benefits” from using costless paper to buy goods made in China disproportinately goes to the top in the US. At the bottom and middle, we’re left with devastated communities, deaths of despair, and half the country going down the rabbit hole known as the “Cult of Trump”.

Personally, I don’t see this outcome as “the greatest deal we could have…”

Most of the “benefits” from using costless paper … TiPS

Actually, inexpensive fiat is the ONLY ethical form of fiat lest the taxation authority and power of government is misused to benefit private interests such as gold owners and would-be fiat hoarders (via deflation).

No, the real problem with fiat isn’t that’s it’s inexspensive but that it is created for private interests (e.g.for banks and asset owners) and that, except for mere coins and grubby Central Bank Notes, only private depository institutions may even use fiat.

taxation authority and power of government is misused to benefit private interests such as gold owners and would-be fiat hoarders (via deflation).

Yeah, instead it is misused to benefit private interests such as stockholders, bondholders, and asset holders in general. In this way the grifters can get so much more since their assets are not physically constrained by how much physical gold there is. In the current schema, the central bank determines the value of commodities through three card monte and a Plunge Protection Policy. IMO it’s a fine line between socialism and fascism, and we have embarked decidedly in favor of one of those two frameworks. Guess which one I think it is?…and I guess I just revealed to myself what I think after reading this post. Our country is extracting it’s value for the sake of several powerful corporations and favored constituencies. The theft is being carried out by running a trade deficit, but IANAE…

instead it is misused to benefit private interests such as stockholders, bondholders, and asset holders in general. tegnost

Yes indeed but the solution is not a (literally) stupid shiny metal but an ethical money system.

Sorry, my focus here is on the so-called benefits from the trade deficits–China (et al) hold pieces of paper while we get tangible goods. Good in theory, but not working out so well in practice.

I agree that trade deficits are not good since they hollow out a country’s manufacturing ability as we just discovered to our National sham with the protective equipment shortages.

But we should consider why foreigners would even want our “pieces of paper” and the bad reasons are at least two-fold:

1) Positive yields/interest on inherently risk-free US sovereign debt; ie. welfare proportional to account balance.

2) Foreigners may buy US land.

Re: foreigners may buy US land.

There is some history with foreign entities buying USA land (example, the Japanese and the Pebble Beach Golf Course). This did not work out well for them.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/realestate/1992/02/22/struggling-with-debt-japanese-developer-sells-pebble-beach-golf-links/870835ec-3687-463c-b427-81e17d7af843/

If a foreign entity is concerned about the future value of the USA’s currency or the stability the USA, portable assets that can be removed from the USA (factories, tools, intellectual property) would seem to be far preferable.to land

Exchanging foreign dollars for USA land while maintaining the USA government’s ability to tax that land (and charge for utilities/security and infrastructure support) could increase the apparent risk (and assigned value) of foreign owned land in the USA.

Foreign owned land can also be nationalized, as US companies have found in foreign countries (and USA military actions have been launched to prevent)..

If a foreign entity is concerned about the future value of the USA’s currency or the stability the USA, portable assets that can be removed from the USA (factories, tools, intellectual property) would seem to be far preferable.to land John Wright

Then let’s add this as an ADDITIONAL bad reason for foreigners to desire US fiat and outlaw that too. (Though it’s questionable that the winners in a trade war might even want much of the productive machinery of the losers except for scrap.)

Besides, as long as we have homelessness and rent-slavery in the US, can it be legitimately argued that we have land to spare for foreigners?

We have run trade deficits almost every year since 1940. In all those years, how has our economy done?

And in all those years, foreigners have wanted U.S. dollars.

As for COVID protective equipment, are you suggesting that the U.S. should be able to manufacture every possible need on a moment’s notice? How about, if we just continue to buy some of what we need, as we have done since before WWII.

Isn’t it amazing that people continue to issue warnings about something that has been going on for 80 years, successfully. Don’t people read history any more?

Are you arguing that welfare proportional to account balance and foreign ownership of US land are good?

If foreigners can out-compete us then fine since I remember the crap the Big Three automakers foisted on US when they could get away with it.

But let’s remove all bad reasons for foreigners to desire US fiat and then we’ll have properly balanced trade.

” . . . not working out so well in practice” ??? Really?

The U.S. has run a trade deficit every year since 1974. What is the “practice” to which you are referring?

There is nothing comparable to the impact China had on trade deficits and manufacturing employment from 2001 to 2007 (a non-recession impact).

It seems fanciful to me that we will somehow get people in the US to adopt the 10 commandments to prosperity under MMT anytime in the near future. The propaganda machine is controlled by the elite, and now the Trump cult are cocooned in their own social network bubble. So if we can only get them to no longer fear socialism….not even in my children’s lifetime will this happen.

Also, in the real world, the elites in the west are gearing up for battle with China (and Russia), so if we take things to their logical conclusion for the US and let China produce all of our goods in exchange for our paper, who will supply those goods when the conflicts begin or next pandemic occurs? With apologies to the late Bill Greider, it’s not one world ready or not….

Maybe we will adopt Yang’s proposal sooner than later, and maybe the global elites can all get along? Maybe….However, in the meantime, we’ll continue to play by their rules where jobs do matter to the communities in which they’re located.

Yes. The problem with fiat is what we do with it. The left can dream up all sorts of fabulous uses for it, but what WE actually do with it is give it to the wealthy. This is the problem with MMT. It requires a sense of community responsibility and incorruptibility that we don’t possess.

The “devastated communities, deaths of despair, and half the country going down the rabbit hole” are not caused by trade deficits. They are caused by people fearing “socialism” more than they fear the above-mentioned devastation.

So they vote against Medicare for All, Social Security for all, and every other benefit to the middle and the poor.

These are people who think federal spending is “socialism.” (It isn’t).

There is an penalty for ignorance.

The “devastated communities, deaths of despair, and half the country going down the rabbit hole” are not caused by trade deficits.

No, they’re caused by the mass-exporting of high-value-add production chains which once provided well-paying jobs, and which are reflected in perpetual huge trade deficits. Perhaps you should have made an effort to actually comprehend Yves’ reply to your OP before adding multiple inane followup comments?

Which “high-value-add production chains” have been exported? Most of the jobs “exported” seem to have been low value-added handwork.

Seem to whom? Go to a hardware store, check out the stuff. DeWalt battery hand drill: DeWalt of Baltimore has their name on it, but the “Made in” says China. Take off the battery, and you find “JAPAN” engraved on the inside. Most of the stuff I’ve checked is like this. Kidde Smoke/CO alarms: China. Long-nose pliers: China.

Manufacturing jobs are only considered low value added handwork by those who have never had a manufacturing job. All jobs require skills to do well.

If the US emits infinite dollars, will that create infinite coal, gas and oil? Will that make topsoil infinitely deep? Will that make plants grow infinitely fast? Will that make the atmosphere infinitely carbon-skyflooding capable with zero climate outcome?

Will an infinite number of dollars bring back the Carolina Parakeet? Or the Passenger Pigeon?

Ideally we should be well on our way off of gas oil and coal. Inflation will take care of the rest.

I was trying to get at the idea that infinite dollars is not the same as infinite wealth. Because money itself is not the same as wealth.

I don’t take issue with your premise that imports are a benefit. They aren’t the problem.

The problem is the lack of government investment in domestic industrial capacity, especially in strategic terms — there are some things that it is simply dangerous to lose the capacity to produce.

A second problem is the lack of government investment in employing its people when imports render their labour surplus — leading to a host of social ills.

Fixing those two problems are the current challenge. Unfortunately, US leadership is not up to the task, mired as they are in the neoliberal nonsense peddled by the oligarchs of the donor/owner class …

When imports are brought in from places with slave wages, anti-social anti-safety-standards, anti-environmental anti-standards, etc. . . . . and are thereby priceable-for-less because less money is spent to produce them . . . . because victim classes and victim countries are forced to eat the un-paid-for costs for free . . . . so that the Free Trade Racketeers can import them into the US to work the Differential Costs Arbitrage Rackets . . . . then these imports are a pure destruction tool.

They are intended to destroy and exterminate domestic industry and they do that because they were precisely engineered to do that. Or rather the Free Trade Agreements were designed to do that.

So no. In a Free Trade Oppression context, imports are purely destructive to the targetted country.

Free Trade is the New Slavery. Protectionism is the New Abolition.

Just seeing the headline reminds me that “President Biden” sounds just as unlikely, cringeworthy and dangerous as “President Trump” and I predict little to no change and any change that occurs will make things worse.

But then again, I am an optimist…

Biden and McConnell will conspire together to bring back the BiPartisan Catfood Conspiracy against Social Security. That is exactly and literally what Biden means by “we can work together with the Republicans.”

Tariffs are non-negotiable, the question isn’t so much if we need them but how much and whether or not it’s paired with a larger tax on capital movements out of the country. Global trade is just a reflection of global capitalism, in order to manage it taxes based on movement will have to be introduced at some point. For example, an oil tariff is one of Trump’s few good ideas as it’s one of the few that could convince Americans to stop being addicted to oil. Same for plastics, whose trade cycle is probably going to poison the ocean because most of it is dumped in third world countries at it’s end-of-life. Change here requires taxation. Looking higher, international fiscal services that own all this should be recognized as what they are (gambling) and taxed accordingly as well. The taxes then pay for things like schools, healthcare, and government provided housing.

If this can’t happen on a national level then it has to happen on a continent wide level. This can already be seen in the USMCA, which while imperfect contains Labor considerations that Biden will be using as a baseline. The severe differences between the west, the east and the global south prevent a healthy trade dynamic in the first place. There needs to be some sort of barrier, or at least tax scheme, to control the excesses that grow when these systems’ markets contact each other.

An oil tariff transfers dollars from the private sector to the federal government, where they are destroyed. Not a good idea for the economy to reduce the money supply.

Raising the price of oil might reduce its usage — if a substitute can be found — but it also will cause inflation and wreck the economy.

Federal taxes do not pay for schools, healthcare, or housing. In fact, federal taxes pay for nothing. They are destroyed upon receipt. (If you disagree, let me know how much money the federal government has.) See: https://mythfighter.com/2020/12/10/test-your-friends-these-10-true-false-questions-will-determine-whether-they-understand-the-economy/

The federal government does not use taxes. Rather, it creates new dollars every time it pays for things. That’s called “Monetary Sovereignty.”

Even if the federal government collected $0 taxes, it could continue spending, forever.

(By contrast, state and local governments DO use taxes for spending. Huge difference. They are monetarily NON-sovereign)

That argument against tariffs is an argument against all taxes. And indeed, this isn’t a time for tax hikes, but tariffs protecting strategic production are in my opinion one of the best taxes. And pollution tariffs discouraging the outsourcing to arbitrage weaker environmental protections are a good idea as well, I think. Inflation can be a problem, but to say that we have room to raise interest rates is an understatement, and as you said, taxes are deflationary. Even oil taxes. I think that Yves likes tariffs to protect jobs, which isn’t a terrible use, but I see no shortage of things to do. It’s funded demand for employment that is scarce, and I think that a UBI would solve that more elegantly. Increase demand from the masses, and demand for employment will rise. Yves way cuts into the benefits of trade a bit, and tariffs can lead to retaliation, but they are still far superior to the payroll and income taxes that we use now. And taxing improvements on real estate, Blech…

> To improve our balance of trade, we should make better and more advanced products and services.

I like (/s) the American-centric “we are the best and brightest” that underlies this statement. The Germans? The Chinese? Anybody else on the 7 continents? Well you will all just eat our dust, if we focus a bit. So there!

At least we have an economic analysis that quietly steps away from “sell them financial products”. Sigh.

I worked for 30+ years in the electronics industry (manufacturing and product design).

I remember being on a conference call with very sharp people in mainland China, Malaysia, Singapore and the USA about a manufacturing issue.

I visited well equipped and staffed factories in Singapore and Malaysia.

And I traveled to Norway, Austria and Israel to visit technically adept companies.

There are many “best and brightest” around the world and for the USA to believe it can decide to simply “make better and more advanced products and services” is pure hubris.

After all, US based Intel has been unable to build to the finest geometry that Taiwan Semiconductor can.

From https://www.livemint.com/companies/news/intel-stunning-failure-heralds-end-of-era-for-us-chip-sector-11595647983933.html

““With the latest push out of process technology, we believe that Intel has zero-to-no chance of catching or surpassing TSMC at least for the next half decade, if not ever,” Susquehanna analyst Chris Rolland wrote in a research note.”

Yeah, financial products, with periodic bubbles, is the product for the USA to sell.

Ah, so Intel represents the entire US electronics industry? Color me shocked that a large debt-heavy company doesn’t have problems with a newer foreign firm with newer factories. Especially as new manufacturing processes proliferate, there’s no reason to think newer chip companies can’t exist. We’re already seeing lightbulb production return to the US largely because LEDs don’t require the huge amount of specialized machinery glass-based bulbs do.

Eventually someone will figure out how to 3D print a computer chip and a whole new cottage industry of computing will emerge.

..not that I disagree about the constant fiscal bubbles blowing up. But this is endemic to all capitalism, which the entire planet suffers from not just the US.

Lightbulb production will be from the few remaining century-old machines that have not been scrapped.

Perhaps one can observe an emergence of a new Godwin’s Law 2.0 for internet discussions of technology.

https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Godwin%27s_law

“Godwin’s Law 2.0” could have that internet discussions of technology will mention “3D printing” as eventually solving any resource/technology problem.

Personally I think there are good thermal reasons why a full 3D chip is unlikely. Also the smallest elements on next gen process are about 10 atoms wide, so there is a limit to how much more gains will be made in the semiconductor industry by simply shrinking process. We should probably be expecting a continuing deceleration in chip performance gains, consolidation because the last bit of distance will get really expensive. There will be a short window when better more modern design gives a nice edge. (Apple M1 is an example.) Eventually though the steady improvement in computing power will Peter out and it is going to take a lot more work to move the world forward in that dimension. The endgame will play out over the next ten years.

Just read this somewhere else this morning and seems to fit most questions of the day –

“Because our government, institutions, and large businesses are hopelessly corrupt…”.

The interchange on the road to turn back was passed in 1992. Now just waiting for the vehicle to fall apart or blow up.

Dollars flow out because there is a need for them for trading. The dollar is strong because it is the world currency. In theory this is good for the USA. We print money and get real stuff in return. However, it hasn’t worked that way because we print money and buy bonds with them and drive up asset prices. If we just printed money and handed it out to people so they could spend that fake money on free shit, the dollar would fall and our exports would become competitive. Or not and in that case we would just keep getting free shit. Win win.

To say that America has no “official” industrial policy may be true, but it has a de facto industrial policy which is destroying America. In many ways the parallels to the coal industry practice of mountain top removal mining is appropriate.

Basically, American CEOs acting together with Wall St are selling the industrial base to foreign countries. American CEOs sell or give away our technology, factories and jobs to China, Mexico, Malaysia, Vietnam, etc. The end result is Detroit:

Decline of Detroit https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decline_of_Detroit

This policy of just selling America out for a quick buck will never get formally written down anywhere because at that point it becomes so obviously a means to destroy a country, but make no mistake, it is our FORMAL INDUSTRIAL POLICY and it WILL happen to every company/industry that can be moved.

Reading Michael Hudson’s Killing the Host. One very important aspect of U.S. industrial policy is the share of GDP bound to the FIRE sector, which I think is near 40% now. That would mean that 3/5 of the economy is producing to support the entire economy.

Money that the FIRE sector removes to up-bid existing assets is removed from circulation just as surely as money that vanishes into federal taxes.

That means that costs to the industrial economy are boosted to perhaps 167% of what foreign industries need to pay. It’s hard to imagine frugalities, reduced wages or whatever, that could overcome a competitive handicap like that.

Robert Malcolm Mitchell inveighs against reducing the money supply – here are the dire results.

As much as I think your analysis of this is correct – I would urge that we seek a more China oriented solution to this particular problem.

When China has a problem with a rich company CEO, they KILL HIM. This leads to extremely effective unspoken industrial policy.

[Was composing this offline – as I went to post it I see Larry Y above beat me to the Bell Labs mention and the crucial and now-neoliberalism-gutted role of *corporate* R&D funding alongside that of government.]

“Don’t we export the best products and services in the world?” — Maybe 50 years ago we did, but since then our corporate C-suiters, in a close tango with neoliberal econ and policy elite revolving-door “public servants” in governent but in reality serving financial interests have been busily exporting the best product and service-providing jobs and technologies in the world. I believe Michael Hudson and other “heterodox” economists have spent large portions of their careers covering this, e.g. Hudson in his book Killing the Host.

“But U.S. government funding for research and development (R&D) has been declining as a percent of our national income for more than 50 years.” — True, but omits another room-sized elephant: *Corporate* R&D funding, especially the truly foundational-technology variety which sometimes needs decades to pay off (and not all of which ends up doing so), the kind outfits like the late great Bell Labs were famous for, has been plunging due to Wall-Street-rewarded short-term “loot-n-scoot” profiteering. The same kind of next-quarter’s-numbers-über-Alles profiteering that has driven the aforementioned hollowing out of a once-world-leading goods & services economy via mass-scale offshoring.

And good luck with the “what Biden could do” thing – isn’t he already nattering about reviving the TPP? Dude is a neolib to the absolute core, a loyal career-long servant of Big Finance.

I dunno, I still think all trade is based on some obscure carry trade and profit skimming. Cheap manufacturing still relies on exploiting the environment and labor. Why can’t each country produce what it needs cleanly, do its own recycling and live sustainably? The part I liked was Vague’s promotion of government funding for essential industries. Instead of applying that money to manufacture trade goods, let’s just manufacture what we need to start up an environmental clean-up industry and put everybody to work. The biggest reason the world is now a toxic dump is overstimulated trade between competing nations. What a bad joke.

“Don’t we export the best products and services in the world?”

No, no you do not. 4 paragraphs in and I can already see we have a another delusional American who believes the smoke blown up their arse.

From a Paragraph up

“That has been our advantage for 150 years—so much so that our product and service superiority is almost taken as a given.”

…ok I don’t know what this author has been smoking, but I need some. It takes a special kind of naïveté to believe this. So its either ignorant or disingenuous to peddle this nonsense. The height of American quality production is 1935-1975 in my opinion and I will admit my knowledge is certainly lacking and their will be products or services that peaked outside that range…

All that said, Americans need to stop drinking the Kool-Aid and understand, your not as great as you think you are, your grandfathers and great-grandfathers were not as great as you remember them.

You got lucky that your enemies made bigger mistakes then you in 1(!!!) war, WW2. (I shouldn’t need to explain why you get no credit for WW1)

Ill give you a run down of Americas greatest hits:

1. “Modern Democracy” … too bad we are in a Post-Modern world and you’ve done nothing to update the formula.

2. Culture-Exportation and Marketing… essentially the “American Dream” the “Land of Opportunity” and the Hollywood master propaganda machine

3. 1945-1965ish, Post-WW2 really was your golden years

4. Saving Western Europes hide twice.

5. The truly great achievement… a real, honest *Middle Class* At some point, in some corners, in some houses.. being an American was pretty great, new gadgets, a decent standard of living, and for those at the bottom a true path upwards. Which for most of the worlds history it wasn’t possible to create a true “Middle Class” But that was then, and this now…

4/5 of those positives do not make you exceptional, instead they have only blinded you to your future destruction. Your education bas been failing for 20 years, your military is addicted to failure and bloated on money, your culture is on the decline, population divided and violent, government inept and corrupt, constitution old and rickety, history short and lacking, science is no longer focused on R&D, but on chasing dollars with vapid “studies”. Art… pfft, you don’t make art, you make shlock for the masses and CGI nightmares that sell in Chinese Theaters.

I don’t hate you, I pity you. Which says alot about me as a person and the upbringing my parents gave me, because you don’t deserve pity, you deserve utter contempt and destruction. I shall not have to wait much longer

Good riddance to the American Empire, long has she reined.

Excuse my horrible grammar and condescending tone. Its been a long…. horrible decade and the start of the next one* has me filled with exhaustion and dread.

(*New Millennium starts in 2001, new Decades start on 2011,2021? No?)

You are right Wyatt. I could add a few things to your list, beginning with our “healthcare” carnival; our refusal to provide jobs for our young generation but forcing them to take out loans for their absurdly useless college educations (all based on a free market philosophy since 1980); our pretense about getting CO2 down (we’re just exporting it); our 3rd world infrastructure; our nonexistent housing; etc. I think your point about our rickety constitution is right on. I’d like to understand why we keep doing things that never work. Einstein must be rolling in his grave. It’s like some perverse article of faith – “freedom, justice and the American Way” as Superman always maintained but nobody ever achieved. Actually I don’t think we are stupid – we’re just too exhausted to do anything. Not good.

Thanks for this. You note 1975 as the end point of quality production and a rising Middle Class. I agree. That was also the point when the new thought leaders in the Dem party decided to quit/abandon/destroy the New Deal philosophy of govt and hop on board the neoclassical (neoliberal) economic train. These 2 things happening at the same approximate time could be coincidence. Then again…. Here’s an interesting article.

FDR Knew Exactly How to Solve Today’s Unemployment Crisis

https://scheerpost.com/2020/12/17/fdr-knew-exactly-how-to-solve-todays-unemployment-crisis/

This idea might or might not work; it’s aimed at getting regular people working again at decent wages. That’s more that the Congressional Dems (big govt bad, deficit spending bad) currently offer or even consider, imo.

And from a Thomas Frank interview:

Thomas Frank: How the Democratic Party Became a Vehicle of Aristocracy

‘More than six years ago, a study by Princeton University Prof. Martin Gilens and Northwestern University Prof. Benjamin I Page made headlines for concluding what many Americans may have already known: the United States is an oligarchy, not a democracy.

….

‘ “The Democratic Party has very much become a vehicle of the aristocracy, of plutocracy,” says Frank. “One of the reasons for that is because liberalism in its modern-day incarnation not only has moved away from and forgotten about its past as a working-class movement, but [provides] a rationale for plutocracy. “ ‘

https://scheerpost.com/2020/12/04/thomas-frank-how-the-democratic-party-became-a-vehicle-of-aristocracy/

About ‘Don’t we export the best products and services in the World’ directly: this is a longish quote from the above Scheer-Frank interview linked above.

This is Robert Scheer speaking.

….And Ronald Reagan–what happened was when he became the spokesperson for General Electric, they took him around to every plant. And Ronald Reagan, after all, had been head of the Screen Actors Guild, and he claimed to be on the side of labor unions. He was–his beef was not with labor unions originally. And he would talk to people. And in these GE plants, they would tell Ronald Reagan, no, we have a great health system, we have great working conditions, and we have a very strong union. It was the united electrical workers, originally a progressive union that got redbaited out of existence by McCarthyism, and then the international united electric workers took over, but they were also a pretty good union.

And so Ronald Reagan, when he was celebrating GE, was celebrating what used to be considered an enlightened capitalist company that paid good wages for American workers. But when Ronald Reagan was president [Laughs] and you had the savings and loan scandal, by the end of his presidency, he became disenchanted with the idea that just big business would always do the right thing. And what happened with General Electric, they ended up getting into banking. GE Capital became the major source of income. They got involved very much in the housing scams, and all that. And two out of three jobs, by the time the housing crisis came along, they had shifted abroad. They were not this great American employer, company. …

So we did export a lot of great things: jobs, R&D, intellectual technical infrastructure, etc. All those exports are a net loss for the US as a whole, imo.