Yves here. At the risk of having readers deem me to be a philistine, I have to confess to assuming John le Carré was a guy-spy-action author. Not that I don’t regularly read male-oriented fiction (I love sci fi) but aside from Graham Greene, I’ve never been a fan of spooky novels. Now that I have learned that le Carré was subtle and subversive, I can now look forward to sampling and hopefully enjoying his work.

By Anthony Barnett (@AnthonyBarnett), the founding Editor-in-Chief of openDemocracy (2001-7), the Co-Director of The Convention on Modern Liberty (2009), the first Director of Charter 88 (1988-95). He was a member of the editorial advisory group of the Bureau of Investigative Reporting (2014-18). Anthony has authored four books and edited one collection, and co-authored two books and co-edited two collections of essays, listed here. He also sits on the Board of The Open Trust. Originally published at openDemocracy

On his death, the establishment is patronising England’s great novelist as a Cold War figure, rather than confonting why he hated them.

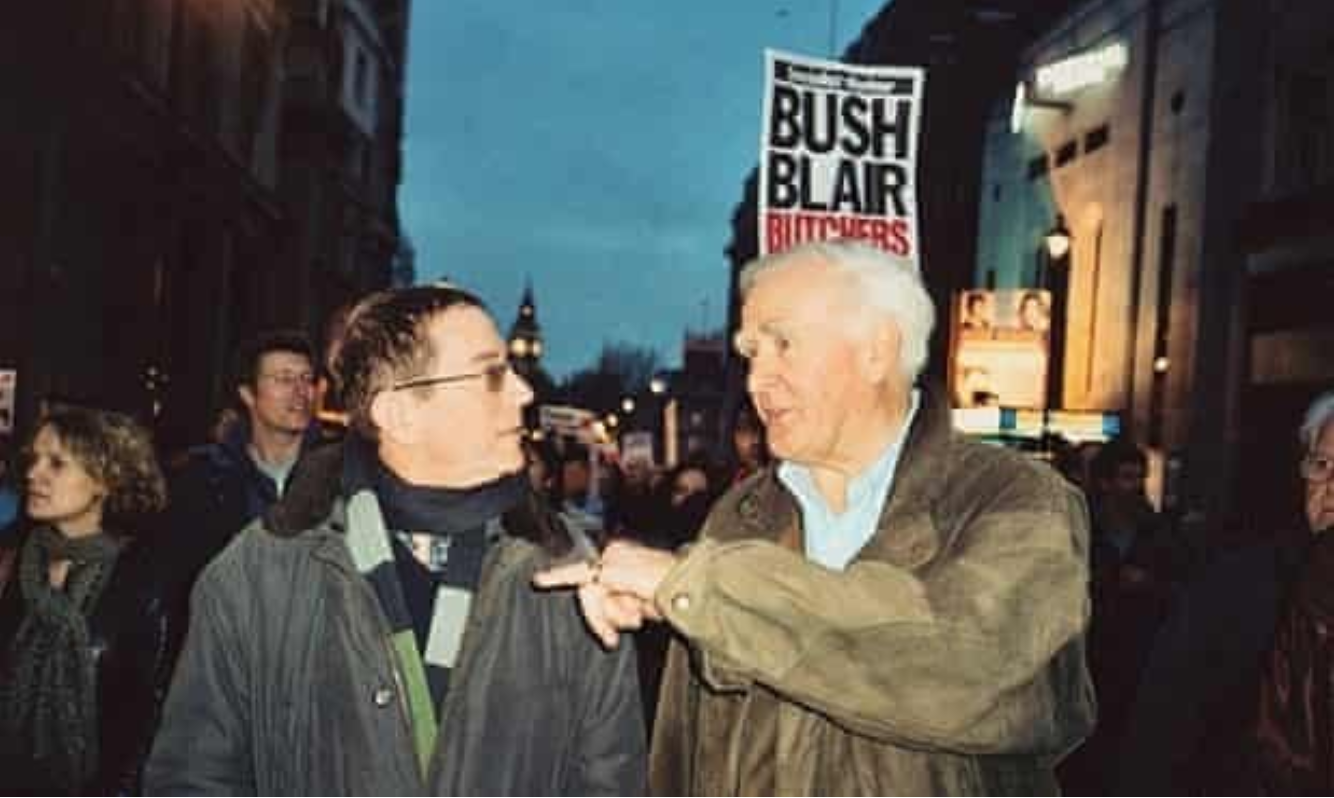

David Cornwell and Anthony Barnett demonstrating against President Bush’s visit to London, November 2003, photo Judith Herrin.

The David Cornwell that I knew, who is famous as John le Carré, is a twenty-first century writer, an author for our time and a forensic investigator of its ills.

Overwhelmingly the salutations in his obituaries emphasise his role in the Cold War. They are filled with a stench of stale melancholy for past self-importance. He despised such sentimentality, personally there was nothing nostalgic about him.

Starting with The Constant Gardiner which he published in 2001, he wrote seven novels in this century alone. His theme was the predations of corporate power, the corruptions of finance, the inhumanity of the looting of Africa, the venality of modern capitalism, the abuse of surveillance and the vile penetration of arms-dealing, as politicians danced to the tunes of oligarchs. Often his contemporary work is described as ‘angry’ as if his views could be dismissed as the weaknesses of old age. In fact they were a tough, always carefully calibrated, exercise of hard judgment.

They mattered because of his fame.

This was exceptional and it did not come just from his being a ‘best seller’. He became an event when The Spy that Came in from the Cold was published. He personified the correct belief that something funny was going on, that we did not know about, and that power on our side was not all that it seemed. This was then reinforced by the films and TV adaptions of his work and his indefatigable productivity.

He was indeed a subtle writer, who recounted the ambiguities of our own side without ever conceding a moral inch to Stalinism. His capacity as a great story teller made his books literature. His overview shaped the perception of the Cold War world.

But in addition there was something self-indulgent and narcissistic about his popularity. Americans loved the way he allowed them to project their own bad faith onto the Brits while feeling morally superior to the declining empire. They made him genuinely wealthy.

But he did not give an inch to US power or Israeli aggression.

He enjoyed playing up the ambiguity, the weaknesses and corruption of power and money, and the vacuum at the heart of those who purport to represent us. At the same time he absolutely refused to collude with or become a part of it – hence his rejection of Anglo-Saxon honours.

For his self-presentation as a chronicler of deception was itself a mask. It veiled an adamantine, steadfast commitment to fundamental integrity.

Integrity is always work in progress, and is something that needs to be protected. He understood this well and was controlling about his influence and reputation (which made life hard for his biographer Adam Sisman). One deception that helped him was the use of his writer’s name John le Carré. His real name was David Cornwell. In the last century he deployed the device to keep his public writing and his private life distinct. The David Cornwell and John le Carré of this century, however, became two sides of the same person – giving interviews and performing.

This John le Carré, the David-Cornwell-who-was-himself, the writer who was “becoming real” entered the early life of openDemocracy and supported it at a critical moment.

It came about because he was writing Absolute Friends whose hero was a revolutionary in 1968. David himself had driven past a 60’s demonstration: who knows I might have been on it. Had we met then we would not have hit it off. Thirty years later, in 2002, he wanted to check his manuscript with someone from the other side of the car window and Tim Garton Ash suggested he contact me. I was happy to help and we clicked.

When the book was published I was delighted that in the conclusion, when the story of THE AMERICAN RIGHTISTS’S CONSPIRACY AGAINST DEMOCRACY was revealed, it was in “a not-for-profit website dedicated to transparency in politics”. Much more important, he had dissected Steve Bannon before he even became Steve Bannon.

David came to the office of our non-fictional website for a meeting over sandwiches with the staff to discuss Iraq. Out of it came his article in The Times in January 2003, ‘The United States of America has gone Mad’. It linked to the openDemocracy debate of writers on the coming Iraq war, led by his brief contribution (reproduced below).

The war was a historic turning point in fact. The depth and clarity with which he saw this also changed him. No longer was there any ambiguity in the exercise of power by Washington and London. With extraordinary lucidity he described the change in himself through his hero in Absolute Friends, Ted Mundy.

So what had happened to him that hadn’t happened before?

He’d weathered Thatcher and the Falklands … The lies and hypocrisies of politicians are nothing new to him. They never were, So why now?…

It’s the knowledge that the wise fools of history have turned us over once too often, and he’s damned if they’ll do it again.

It’s the discovery, in his sixth decade, that half a century after the death of Empire, the dismally unmanaged country he’d done a little of this and that for is being marched off to quell the natives on the strength of a bunch of lies, in order to please a renegade hyper-power that thinks it can treat the rest of the world as its allotment…

So Mundy redux marches … with a conviction he never felt before because convictions until now were essentially what he borrowed from other people…

It’s about becoming real after too many years of pretending, Mundy decides. It’s about putting the brakes on human self-deception, starting with my own. (pp 255-7)

We marched with him and his wife Jane in London against the visit of President George W Bush in November 2003. With his bright eyes David picked out a demonstrator with large polished boots as a policeman.

In 2006, enraged by the Israeli attack on Lebanon and with his views no longer so welcome in the mainstream press, he published a surgical condemnation in openDemocracy and in support of Saqi Books.

When we needed to launch a funding campaign he gave us its lead endorsement:

“Let’s support openDemocracy to the hilt. Intelligent, unbought, unspun opinion, uncomfortable but necessary truths and a lot of good horsey argument: heaven knows they are in short enough supply!”

I enjoyed “horsey”, a superbly ambiguous term of praise, signalling with exactitude the site’s publishing of arguments that while they smelt of life may not be ones you would want to live with!

In 2013, I helped a little with his rendition of New Labour treachery in A Delicate Truth.

I thought of David as indestructible – and still do. He was a man of the future that we need to have.

Last year, in a 60 minutes interview with Steve Kroft to publicise his most recent anti-Brexit novel, Agent Running in the Field, this most European of writers whose books covered the world was asked if he felt he was English. His reply was typically exact as he rephrased the question.

“What kind of Englishman at the moment? Yes, of course, I’m born and bred English. I’m English to the core. My England would be the one that recognizes its place in the European Union. That jingoistic England that is trying to march us out of the EU, that is an England I don’t want to know”.

He is everything his country could have been, that it should be, that, in the hands of its contemptible leaders, it is not – the England that it can become, but only when the generation that have betrayed it, Labour and Conservative, has left the scene.

John le Carré’s Contributions to openDemocracy

28 August 2006, Israel invades Lebanon

So answer me this one, please. If you kill a hundred innocent civilians and one terrorist, are you winning or losing the war on terror? “Ah”, you may reply, “but that one terrorist could kill two hundred people, a thousand, more!” But then comes another question: if, by killing a hundred innocent people, you are creating five new terrorists in the future, and a popular base clamouring to give them aid and comfort, have you achieved a net gain for future generations of your countrymen, or created the enemy you deserve?

On 12 July 2006 the Israeli chief-of-staff granted us an insight into the subtleties of his nation’s military thinking. The military operations being planned for the Lebanon, he told us, would “turn back the clock by twenty years”. Well, I was there twenty years ago, and it wasn’t a pretty picture. Since then, the lieutenant-general has been as good as his word. I am writing this just twenty-eight days after Hizbollah captured two Israeli soldiers, a common enough military practice not unknown to the Israelis themselves.

In that time, 932 Lebanese have been killed and more than 3,000 wounded. 913,000 have become refugees. Israel’s dead number ninety-four, with 867 wounded. In the first week of this conflict, Hizbollah fired some ninety rockets a day into Israel. Last week – despite 8,700 unopposed bombing sorties flown by the Israeli air force, resulting in the crippling of Beirut’s international airport, and the destruction of power-plants, fuel-dumps, fishing-fleets, 147 bridges and seventy-two roads – Hizbollah upped its daily average of rockets to 169. And those two Israeli prisoners who were the purported cause of all the fuss have still not come home.

So yes. Exactly as we were warned, Israel has indeed done to the Lebanon what it did to it twenty years ago: laid waste its infrastructure and visited collective punishment on a delicate, multicultural, resilient democracy that was struggling to reconcile its sectarian differences and live in profitable harmony with its neighbours.

Until four weeks ago, Lebanon was being heralded by the United States as a model of what other middle-eastern countries might become. Hizbollah, it was widely and perhaps optimistically believed by the international community, was loosening its ties with Syria and Iran and on the way to becoming a political rather than a purely military force, yet today this very force is the toast of all Arabia, Israel’s reputation for military supremacy is in tatters and its cherished deterrent image no longer deters. And the people of Lebanon have become the latest victims of a global catastrophe that is the work of deluded zealots and has no end in sight.

This piece was written in support of Lebanon, Lebanon, to be published by Saqi on 28 September 2006; all proceeds will go to children’s charities working in Lebanon

12 January 2003 High Noon for American democracy.

This is High Noon for American democracy. The rights and freedoms that have made America the envy of the world are being systematically eroded. A new McCarthyism is abroad. Bush tells us that those who are not with him are against him. I am not with him.

The American over-reaction is beyond everything Osama could have hoped for in his nastiest dreams. But this war was planned long before Osama struck, and it is Osama who made it possible. Without him, the Bush junta would have been mired in Enron, electoral scandal and taxation sleaze. Thanks to Osama, Americans are instead being daily misled by their leaders and by their compliant corporate media.

There is a stink of religious self-righteousness in the air that reminds me of the British Empire at its worst. I cringe when I hear my Prime Minister lend his head prefect’s sophistries to this patently self-interested adventure to secure our oil supplies.

“But will we win, Daddy?”

“Of course we will, child, and quickly, while you are still in bed.”

“But will people be killed, Daddy?”

“There will be a few Western casualties. Very few. Go to sleep.”

“And after that, will everything be normal? Nobody will strike back? The terrorists will all be dead?”

“Wait till you’re older, dear. Goodnight.”

“And is it really true that last time round Iraq lost twice as many dead as America lost in the entire Vietnam war?”

“Hush child. That’s called history.”

Where’s the hurry? Iraq is a vile dictatorship, and Saddam is a monster who sits on the world’s second largest oil reserves. But there is ample time to consider how to unseat him before we plunge into this predatory and dishonest war. Leave the UN inspectors there. Convene Iraq’s neighbours. And consider for a moment where the will came from to make this war in the first place.

Americans can still awake to the shame of what is being done in their name.

Britain is half way there. The French and Russians have been bribed and browbeaten into submission. Only the good Germans have so far succeeded in sticking to their silent guns. I wish profoundly that the rest of us Europeans, in the spirit of a nobler President, would declare ourselves to be citizens of Berlin.

Published as the lead contribution to Writers, artists and civic leaders on the War

©John le Carré

I’ve read about five John LeCarre novels and the one thing I’ve learned from them is that people who become spies are never to be trusted – not even your own.

Anyone have any recommendations on where to start with him?

I read Tinker Tailor and wasn’t that impressed. It kind of reminded me of a less fun version of Gravity’s Rainbow, a book that I really like.

I think John Le Carre is an acquired taste – you kind of have to get used to the way he writes, but try starting with The Russia House.

I’ve read that one and ‘The Spy Who Came In From The Cold.’ A common theme was the collision of human characters with human values and emotions with the (often exploitative or dysfunctional) engines of government and state power. ‘The Russia House’ was a bit more optimistic, which probably makes it a better starting point.

Thanks to you both! Might not be my thing but I’ll try it again.

Thank you for this piece.

Yes, a second to the thank you for this piece. I always looked forward to a new novel from John le Carre.

I was so upset with his signing a letter accusing Jeremy Corbyn of antisemitism that I threw his books books in the dumpster. I had read them all. It was only then on thinking back on some of his novels especially The Night Manager that I saw his view of his female characters was that of a dirty old man. A little extreme perhaps but Jeremy Corbyn wasn’t an antisemite!

Very disappointed to hear about this. It’s like finding out that a favourite entertainer is a Scientologist.

Ugh, ditto.

LeCarre wrote anti-Russian propaganda thrillers for the UK/US market. Ergo, a glorious career!

That is shocking. Seems out of character. I wonder if Cornwell was still “with it” when he allowed his name to be used.

Read The Perfect Spy! Best English book of the 20th Century. No, really.

I’d add David’s comment from yesterday’s watercooler here.

Thank for linking to David’s comment which I subscribe in full. Long ago I became a Le Carré fan thanks to the Smiley trilogy (later associated Smiley with the excellent Alec Guiness in his role). I never abandoned Le Carré even if the later books were not as good but he was always interesting.

Rest in Peace, sir!

His best work stands up to anything written in English over the past 60 years. I was pleased to note that many of the obits recognized this. The genre that he often chose was simply a stage set (albeit wonderfully complex and sophisticated) for his mastery. Yves, I envy you if you explore Le Carre for the first time.

I won’t repeat what I posted yesterday, but I’d just add that Le Carré is best understood as the poet of the Cold War spy novel and the decline of Britain as a world power. His genius was to somehow portray an existential conflict, but one necessarily conducted by underhand rather than noble means. With the end of the Cold War, this framework was no longer usable: everything had become smaller and meaner as a result. Some of his better work in later years (I mentioned a few examples yesterday) was on a deliberately smaller scale, with believable life-sized villains. But books like The Constant Gardner, mentioned in the article, whilst it might comfort the author’s political inclinations, doesn’t convince as a novel, because it effectively asks the reader to accept that a multinational pharmaceutical company can serve as a modern equivalent of the KGB.

Le Carré was not anti-British: indeed, he was a rather old-fashioned patriot, for whom the real problem was Britain’s increasing subservience to the United States, and the post-Thatcher progressive destruction of the public service in which he (albeit briefly) worked. It was this that was behind, for example, his opposition to British participation in the Gulf War. Pace the article, Le Carré is fundamentally a novelist of the Cold War, and will be remembered as such. It’s for that reason also that there will never be another Le Carré, even if somewhere there was a another former intelligence officer with the same talent. It’s a bit like Sunset Boulevard: the moral issues are smaller today. Yves, if you want to get started on Le Carré, the place to begin is the Smiley-Karla trilogy, beginning with Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, and the unrelated book A Perfect Spy, whose first half is semi-autobiographical.

I read Tinker, Taylor, Soldier, Spy when I was in my twenties and I was very much surprised by something that I thought I wouldn’t find in any spy novel. It was the detailed description of the players’ psyque in the normal civic life, with their obsessions and their personal histories modelling their professional behaviour. The administrative drama in the spy day-by-day routine living. I also learned about the song.

learnt— my bad with irregular verbs.

You’re correct twice, depending on country.

learned = US usage

learnt = UK usage

An entirely off topic – for reasons I don’t entirely understand, when I hear of Sunset Boulevard, I actually think of Alpha Ralpha Boulevard, and have to make a mental effort to separate the two.

Great story and great writer.

Not entirely off-topic, either. Cordwainer Smith in his real life as Paul Linebarger was at the center of U.S. imperial covert operations and geopolitical intrigue in a way that le Carré in his real life as David Cornwell, MI5 employee, never began to approach.

I saw The Constant Gardener in the theater when it first came out, and I also doubted that the pharmaceutical companies could be as bad as all that.

But not long afterwards there was an article published in the New York Review of Books that stated credibly that the drug companies, shockingly, were a whole lot worse than the movie portrayed them. Maybe the movie just needed a bit more corroborative detail to give verisimilitude — but then again, maybe then it would have ceased to be popular entertainment. Le Carre seemingly understood that mass audiences can only absorb very small doses of truth.

Read Merchants of Grain, find out that in 1972, multinational grain companies sold $1 Billion in wheat to Russia, and neither the Russian, nor the American government wanted to talk about it.

Discover that a grain company, Cargill I believe, bought Model T Fords for all its agents all over the planet so they could drive out to the fields and report on crop conditions.

Find out how being world wide grain monopolists requires owning a monopoly on sea-going transport so as to be able to reroute grain shipments at sea to be able to profit from real-time price fluctuations. (due to famine’s impact) If you want to purloin Italy’s order, in order to send it to Africa instead, you must have immediate access to another ship so as to ensure delivery of the Italian order. And that requires preemptive ownership of the necessary permits and contracts for those ships.

IOW, a lot of multinationals have spies and ‘special operations’ people on staff.

Want proof, try causing trouble for any of the companies ‘competing‘ to partake in operation Warp-Speed.

I regularly reread the books in the Tinker, Tailor series. Generally not front to back , since they are so familiar now, but I dip into them.

I’ll second the recommendations for The Perfect Spy, which was praised by no less than Philip Roth as, IIRC, maybe the best British English-language novel of the last half-century.

The last few novels, on the other hand, often failed to convince.

The bad Big Pharma corporation in The Constant Gardener is doing something in Africa that wouldn’t make sense — as in pay off — in the real world, because le Carré didn’t understand the mechanics of how things work in that sphere and seems to have just bought into the ‘correct’ attitudes from the standard sources.

Likewise, in his last novel, one of the ‘good characters’ is a mouthpiece for full-blown Russiagate and TDS belief. I wouldn’t necessarily assume that what a character believes is what the author, le Carré, espoused, but it did seem like it. In A Most Wanted Man, similarly, there’s a glamorization of a German intelligence protagonist and general glamorization of the European Union — as against the CIA bad guys — that struck me as markedly unrealistic.

Someone else has already mentioned above how le Carré/Cornwell bought into the Corbyn antisemitism line.

I liked The Tailor of Panama. That novel’s plot might be just an updating of Greene’s Our Man in Havana, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. The Night Manager I haven’t read and maybe I should — if anyone wants to advise me pro or con there, I’d welcome that.

I enjoyed The Night Manager. Though from memory is was reasonably close to the spy/action prototype with a le Carré flawed hero character thrown in.

A Most Wanted Man kept me interested but overall was uninspiring and a book that tried to touch on modern topics but I believe in a poor manner.

Personally I loved The Constant Gardener. I loved the mystery about the protagonist. The big Pharma angle didn’t seem to be done well but as a novel it was great. I listened to the audiobook read by the author himself.

The Night Manager was made into a delicious six-part tv series with Hugh Laurie, Tom Hiddleston, and Olivia Colman (plus Tom Hollander and Elizabeth Debicki). I believe that Le Carre approved the script and was on the set for a bit. It’s hard for me to remember the original, so I can’t advise on whether or not to read the novel first.

Le Carre had incredibly good luck with many of the film/tv adaptations of his work. Absolutely first class actors and directors. Much as Alec Guinness isn’t quite like the written description of George Smiley, his (definitive) portrayal in Tinker, Tailor is indelible, so that in reading the novel afterwards one can see only him as the character.

He has had great good luck with his film adaptations. In fact, I find people who really hate to read Le Carre love the movies and TV shows based on his books.

He certainly did, based on the ones I’ve seen (all but the recent two, and the 70s Smiley) I’d say he’s the author who has best been served by the film makers who have adapted their works.

As for the first book to pick up suggestions I’d vote for The Tailor of Panama as a good starting point for a Graham Greene fan.

Agree, Elissa3, I don’t normally like tv series, but The Night Manager, I’ll grant it street cred. Of course a bit over-dramatic, but what tv or movie should not be? Well played, all around.

Off Topic: Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy with Gary Oldman as Smiley and John Hurt as Control is fabulous, and well worth streaming.

I’ve not read the book but the series was quite good, except for the ending which was uncomfortably neat and din’t ring true as a Le Carré ending to me, so I checked the book at a bookstore and flicked to the end – the ending was a lot bleaker.

“After a spell in the British Army, he studied German at Oxford, where he informed on his left-wing students for Britain’s MI5 domestic intelligence service.”

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-people-john-le-carre/tinker-tailor-soldier-spy-novelist-john-le-carre-dies-aged-89-idUSKBN28N0VQ

So what?

If you always insist on perfection in others, you severely limit yourself.

I’m sure he thought he was doing the right thing at the time – remember the Commie scare was a BIG thing, and it infected a lot of people, not just John Le Carre.

I’ve learned that nobody is perfect so you often have to take the bad with the good. And sometimes to get to the good, you have to overlook a lot of faults. I can imagine if you knew about Shakespeare’s private life, no doubt you would criticize him too.

Shakespeare had real feeling for the common people. The detail about Le Carré is consistent with his politico-literary position, namely an elitist saddened that the modern British ruling class is so tacky. Although he endorsed social democratic policies, does he convey genuine concern for the common people?

What dastardly, underhanded, disreputable, infamous behaviour! An indelible stain on Oxford’s good name honour! It’s just not cricket, I tell you!

Everyone knows that it was Cambridge men who went in for spying for the Soviet Union!

The reason for that is found in the article that you linked to-

‘The discovery, which began in the 1950s with the defection of Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, that the Soviets had run spies recruited at Cambridge to penetrate British intelligence hammered confidence in the once legendary services.’

We know all about the Cambridge Five now and it was not unreasonable to assume that there might have be an Oxford Five in this era. Read up on communism among British students in the 1930s. It was rampant.

Thanks for posting this.

I would also recommend the Smiley series to Yves. One aspect I liked was the the way Le Carré interwove the personal and the political.

*spoilers ahead*

Smiley was a human being, with personal affections – a weakness exploited by his arch enemy Karla, a KGB colonel. At the same time, Smiley was always convinced that the one thing that would be Karla’s undoing was his fanaticism, a trait Smiley ascribed to the whole Soviet / KGB system, and which was to him the defining feature of their evil. Alas, Karla’s downfall was not due to his fanaticism, but due to him being a human being, with personal affections. And Smiley brought him down by exploiting these affections with merciless fanaticism.

Rest in peace John Le Carré.

I’ve also never read any of his work because I had the same sort of preconceptions about it that Yves did. Somehow I also missed his objection to the Iraq war and other political writing and actions that would have made me realize that I may have mis(pre)judged his books. Looks like I have some reading to catch up on.

“The Mission Song” and “Absolute Friends” were both very good, devastating.

From The Guardian review of “The Mission Song”: “But what makes The Mission Song most impressive is Le Carré’s refusal to let anyone get away with anything. His targets are the thievery and bloodshed that hide beneath the usual pieties about peace and freedom. Western machinations need willing partners. Le Carré hits the foreign suits as hard as the indigenous African tunics who come together to ruin another lovely piece of the continent. The Mission Song is a light-hearted tragedy, a strangely sunny tale of despair in which a Congolese Candide with nothing but his unassailable innocence somehow sees it through.”

The “somehow sees it through” line is misleading…

Best…H

Hank4KY.com

If you want a bit of a What The Family Blog moment, go to the Opendemocracy link and scroll down to the submission that directly follows le Carre’s. SOmeone named Roger Scruton who I was formerly blissfully unaware of seems to be writing in favor of the invasion of Iraq:

“AMERICAN INTENTION, TO LIBERATE NOT TO ENSLAVE

When assessing US foreign policy it is important to remember that America has often intervened around the globe, and is unique in seeking instantly to withdraw thereafter.

It withdrew from Europe after the two world wars, and from Korea, Japan, and (wrongly) Kuwait and Iraq last time round.”

Even for someone who is going to write in favor of that war I still find it amazing that they could start out by writing something so blatantly, obviously, objectively untrue. Not surprised when I looked up his bio and found among other things that he was writing pro-tobacco articles while being paid by the tobacco industry.

Ah I didn’t know he died, a shame. He was a pretty good writer, occasionally very good. I stayed away for a while for similar reasons of pre-conception but he’s worth a look. I haven’t read his 21st century work (except his autobiography, The Pidgeon Tunnel, which is quite fun) or the big Smiley series. The Spy Who Came in From the Cold is sort of the go-to recommendation. I’d also recommend Call for the Dead, (iirc) his first novel and the first featuring Smiley. It’s impressively atmospheric, and I enjoyed his denigrating descriptions of Smiley.

The abiding theme of his work for me, the most enjoyable, is the multifaceted mediocrity of spies and the states they work for.

To that end, there’s a great movie called Hopscotch with Walter Matthau – a film based on a dramatic spy novel which was rewritten as a comedy. I like to think le Carré would’ve approved of it, even if it wasn’t based on his work.

A superior writer of his generation – who occasionally deals with similar themes – whom I would recommend is Michael Frayn.

“In capitalist America economic repression of the masses is institutionalised to a point which not even Lenin could have foreseen. . . . ”

“The cold war began in 1971 but the bitterest struggles lie ahead of us, as America’s death-bed paranoia drives her to greater excesses abroad. . .”

Tinker, Taylor, Soldier, Spy

The cold war began in 1917 but the bitterest struggles lie ahead of us, as America’s death-bed paranoia drives her to greater excesses abroad..

The Spy that came in from the Cold I read as a young teenager. It opened my eyes to a world I had hitherto not suspected to exist.

I have never since read any others of his works but will always be indebted to him for that essential part of my education. A fine book as I recall.