Yves here. Many associate sweatshops in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh with “fast fashion,” aka the close-to-disposable frocks made by the likes of H&M. As this article explains, the use of ultra-cheap labor extends much further up the fashion food food chain. And these poorly-paid workers get thrown to the curb when orders fall off.

By Tansy Hoskins, a journalist covering the garment industry and the author of ‘Foot Work – What Your Shoes Are Doing To The World’ and ‘Stitched Up – The Anti-Capitalist Book of Fashion.’ Originally published at openDemocracy

In 2019 the fashion industry generated $2.5trn in global revenues, making it one of the largest industries in the world. But when COVID-19 struck in 2020, it virtually collapsed.

Exports of raw materials from China began to slow in January last year, and subsequent lockdowns around the world meant shoppers stayed at home, retailers shuttered stores, and billions of dollars of orders were cancelled. Thousands of factories faced ruin, and many closed either temporarily or permanently.

In countries such as India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, tens of thousands of workers lost their jobs and thousands more were taken ill as COVID-19 spread through cramped production lines. Where people dared to speak up about unsafe or unfair conditions, they were often met with redundancy or brutality.

Many experts believe the pandemic has illuminated the exploitative nature of the world’s garment supply chains, which have undergone a radical transformation in recent decades.

“The fashion industry is at root an exploitative system based on the exploitation of a low-paid and undervalued workforce in producing countries,” according to Dominique Muller at Labour Behind the Label.

“The system is created in order to protect those at the top while allowing workers to take the biggest hit.”

‘Empty Promises’

From the 1970s onwards, globalisation shifted clothing production from western Europe and North America to the Global South. Garment workers, who were previously direct employees of the major brands, became distant actors in complex global supply chains. In turn, major fashion brands no longer faced a legal obligation to pay fair wages or offer employment benefits.

With exploitatively low salaries, garment workers in the Global South have for years struggled to survive. Saving for emergencies was near impossible, meaning they had nothing to fall back on when the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

“Consumers should never forget this era and what the brands have done with workers,” said Kalpona Akter, the executive director of the Bangladesh Center for Workers Solidarity. “When the time came for them to have our back they left us starving.”

“COVID has shown us the reality of empty promises from businesses, from brands, retailers and manufacturers,” Kalpona continued. “The workers made them profits for years, and gave them a lavish life, but when the pandemic started they just left the workers to starve.”

In a recent study, which interviewed 400 garment workers across nine countries, the Worker Rights Consortium found that even those employees who managed to hold onto their jobs reported a 21% decrease in income between March and August 2020 – with monthly wages falling from $187 to $147.

It is a scenario that Kalpona Akter recognised: “Workers are not getting overtime and in many factories they have been told ‘we are not paying the minimum wage, if you want to work, work, if not – leave’.”

Garment worker families in Bangladesh are now having to make impossible choices to survive. “When they get full wages, 30% goes on housing – it’s not a dream house, it’s a ten-by-ten concrete room, sometimes with no window,” Kalpona explains. “Losing 20% means they are substituting their food and their children’s food because they still need to pay for where they live. Instead of having 70% left, they have 50% left and that means they are starving.”

Across the sea in Sri Lanka, labour rights advocates paint a similar picture of lost earnings. “Workers live for those wages – it is their main source of income,” said Abiramy Sivalogananthan of the Asia Floor Wage Alliance. She explained that many workers in Sri Lanka’s vast free trade zones are migrant workers who support not just themselves but their families in rural villages.

Most garment workers in Sri Lanka also lost their critical December bonus of an additional month’s wage. “The bonus is really important,” Abiramy explained. “Workers usually have plans for that bonus even at the beginning of the year – like they will pay off their debts.”

‘Super Winners’

The pandemic has also created difficulties for fashion retailers. In Europe and North America major retailers – including Philip Green’s Arcadia, the group behind brands including Topshop, Burton and Miss Selfridge – have collapsed. In the US alone, an estimated20,000-25,000 physical shops have closed down. According to a recent report by the consulting firm McKinsey, fashion companies will post a 90% decline in economic profit in 2020.

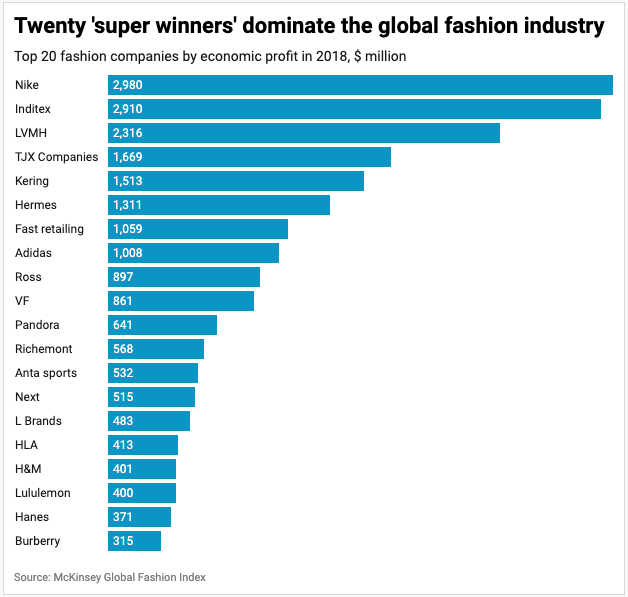

But not all companies are feeling the pain equally. The McKinsey report uses 2018 data to identify a set of industry ‘Super Winners’ – the top 20 fashion corporations based on total annual profits. These include Nike, H&M, Zara’s parent company Inditex, Lululemon, and adidas. From the luxury sector the list includes Burberry, Kering (which owns Gucci), and Hermes.

When the stock market plunged in March 2020, the Super Winners managed to weather the COVID storm while others in the industry battled for survival.

“Through the pandemic period, Super Winners performed better than their peers with 22% higher indexed stock valuations”, the Mckinsey report states. By October 2020, the share price of these corporations was 11% higher than pre-crisis levels.

McKinsey credits the success of the Super Winners to two shared characteristics: a slick digital presence so people can easily shop online, and a strong focus on the Asia Pacific region where the pandemic has not ravaged society as much as in the US and Europe. The report states that “the strong will get stronger in 2021 if stock valuations are a signal of future success.”

Building Back Better?

According to experts at the International Labour Organization (ILO), when the fashion industry rebuilds itself it must be sustainable and adopt a “human-centred future of work”, with fair salaries and working conditions for garment manufacturers in the Global South.

“There is momentum to use this major disruption to the industry as a way to challenge the status quo and build back better toward a more resilient, inclusive, sustainable and equal garment industry,” Tara Rangarajan, head of brand engagement at the ILO’s Better Workprogramme, said.

“The garment sector in some countries continues to be marked by low levels of collective bargaining and significant restrictions on freedom of association. In some cases, lockdown provisions have reportedly limited union activity. Social dialogue is key to moving forward.”

But in the meantime, as COVID-19 continues to disrupt work and health, economic precarity means garment workers are working even when they fall unwell. “Now what is happening is the workers realize they have symptoms for COVID-19, they have a fever, they have a cold, but they start hiding it because they fear that they may lose their job if they don’t turn up,” Abiramy said.

“They take Panadol [a paracetamol], they take vitamin C, just to pass through the temperature check. Because the factories made the rule that if you don’t show up to the work – no money. If you don’t show up to work for a month, you lose your job, even if you are a permanent staff… They don’t have any other means of income and they’ve worked without overtime payments for months.”

As the vast wealth of the fashion industry becomes further concentrated among its top corporations, the profit model has not only pushed the economic pain of the pandemic onto the most vulnerable people in supply chains (most of whom are women) – it has also pushed the social and personal costs of the virus onto the same people.

“We need a new way of thinking,” said Dominique Muller at Labour Behind The Label. “One that puts responsibility for workers firmly on the brands so they can no longer be excused from the continued suppression of workers. One that gives value to the workers making those clothes and one where governments around the world have legislation in place to curtail exploitation, hold companies accountable and ensure remediation of abuses.”

What the US government could do and should have done is negotiate union rights as aggressively as the patent and copyrights of Disney in trade agreements. That way the ILGWU, which supported my mother reasonably well, would have the legal clout to organize and strike in third world countries. And a strike could mean a strike against Nike in four or five countries so that there would be no production. If the producers can spread production out of the third world the unions have to be able to spread organizing over the same area. That should be a the key part of all trade agreements. With Mexico that would mean the UAW would be able to organize the Mexican auto plants where they make cars for the US market with 2 dollar per hour labor. And yes clothing and cars would be more expensive but the workers would be able to buy them. In Germany where I live most people buy German cars at prices significantly higher than the US cost. That being said workers can afford it and at some level understand that the domestic workers are part of the society not to be thrown out of work. And while the prices are higher they are not ridiculously higher suggesting that high wage autoworkers are not necessarily not competitive. Without international unions I can’t see how manufacturing and all work cannot be a race to the bottom.

I’m not sure that would have ever happened since the main point of outsourcing was to reduce the power of unions and workers imo.

It can be a little disheartening to read solutions that increase worker power when the PTB in the industrialized world are set on barriers to labor power such as prop 22. Good post though, nice snapshot of a grim picture.

What surprises me about that graph is just how profitable Lulemon is. I had no idea people spent so much on yoga clothes. Maybe its the desire to look right on all those zoom classes?

A few months ago there was an article here on the Debenhams sit-in in Dublin. Debenhams (Ireland) went bust in a dubious manner before lockdown and the owners tried to use fancy legal footwork to repatriate the stock to the UK while renaguing on workers pension rights. There has been a site in at the main entrance to the department store for over a year, right through Covid, although I notice the number of protestors is down to a handful now. As Debenhams (UK) is now in administration it may have changed the legal context, but I haven’t been following the details.

They make quite a bit of other stuff, including office-to-casual wear (which works for commuter cycling) and things for non-yoga pursuits. They’re apparently quite highly regarded for innovations with their materials and construction. Not sure what their labour practices are.

The solution for surplus workers is not dissimilar from the normalized, acceptable solution surrounding the more routine problem of over production, over supply, and business cycles, more generally, that is, maintaining price floors for consumer goods and price ceilings for wages [disposable workers and a reserve army of labor] , government ‘legislation’ and capitalist ‘efficiency’ notwithstanding.

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/amazon-warehouses-trash-millions-of-unsold-products-say-media-reports/

https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2018/9/17/17852294/fashion-brands-burning-merchandise-burberry-nike-h-and-m

I’d read the Vox piece. Burn clothing to save the “brand.” Spectacularly awful. But typical, imho.

I see Nike at the top of the fashion list. I am amazed to see people walking around with a hat, for example, with the Nike (or other brand logo). A free walking billboard for the corporation. Noted “progressive” Michael Moore is almost always pictured wearing a brand hat for college football or pro sports, mostly owned by oligarchs. Certainly, MM seems clueless as to how the economic system really works. When humans brand themselves, one begins to wonder about their consciousness.

As for Nike running shoes, one might consider barefoot running as described in Born to Run: A Hidden Tribe, Superathletes, and the Greatest Race the World Has Never Seen

https://www.runnersworld.com/runners-stories/a20954821/born-to-run-secrets-of-the-tarahumara/

Barefoot running? Color me skeptical. It depends on where you run: man did not evolve to run or even walk on hard surfaces like concrete and asphalt.