Yves here. While this analysis targets a very important question, the impact of cheap money on racial inequality, its analysis on the balance sheet side looks more robust than on the income side. The post looks at how monetary stimulus disproportionately reduces black employment gains, and then multiples the jobs increase by the average income for black households.

It seems highly probable that that approach overstates income gains since the financial crisis. First, the jobs created have been overwhelmingly low income McJobs, as in low wage and thus likely to be lower than average household incomes. Second, the post crisis job market has also featured a high level of “involuntary part-time employment” as in people who want a full time job unable to find one or even make two part time jobs add up to full time jobs. It seems reasonable to assume that people of color would be more afflicted by those developments and hence “employment recovery” might not be as rewarding as it looks on the surface.

But even with that quibble, this piece confirms what many already know: that monetary stimulus is more effective at goosing asset prices than the real economy, and the existing well off (as in overwhelmingly white top 10% and the finer strata of the richer rich) gain more than ordinary folks, who have higher relative minority membership.

By Alina Kristin Bartscher, PhD candidate, University of Bonn, Moritz Kuhn, Professor at the Department of Economics, University of Bon, Moritz Schularick, Professor of Economics, University of Bonn, CEPR Research Fellow, Member of the Academy of Sciences of Berlin-Brandenburg and Paul Wachtel, Professor of Economics, New York University Stern School of Business. Originally published at VoxEU

Racial income and wealth gaps in the US are large and persistent. Central bankers and politicians have recently suggested that monetary policy may be used to reduce these inequalities. This column investigates the distributional effects of monetary policy in a unified framework, linking monetary policy shocks both to earnings and wealth differentials between black and white households. Over multi-year horizons, it finds that while accommodative monetary policy tends to reduce racial unemployment and thus earnings differentials, it exacerbates racial wealth differentials, which implies an important trade-off for policymakers.

The gap between the income and wealth of black and white households in the US is large and persistent. According to the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), the median wealth of a white household is almost nine times higher than that of a black household. The income gap is smaller (1.7 times) but still large. Moreover, these gaps are as large as they were 50 years ago (Kuhn et al. 2020). Concern about racial inequality has increased recently with evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic is having a disproportionate effect on the black community (Bertocchi and Dimico 2020). These stark facts have attracted the attention of economists (e.g. Mayhew and Wills 2020, Chetty et al. 2018) and policymakers. For instance, Raphael Bostic, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, recently stated that the Federal Reserve “can play an important role in helping to reduce racial inequities and bring about a more inclusive economy”.1

A prominent line of thinking is that an accommodative monetary policy lowers unemployment rates and increases labour income for marginal workers, who are oftentimes low-income and minority households. This is what Coibion et al. (2014) call the earnings channel of monetary policy. More specifically, Carpenter and Rodgers (2004) show that a monetary policy accommodation reduces the gap between the unemployment rates of black and white households.

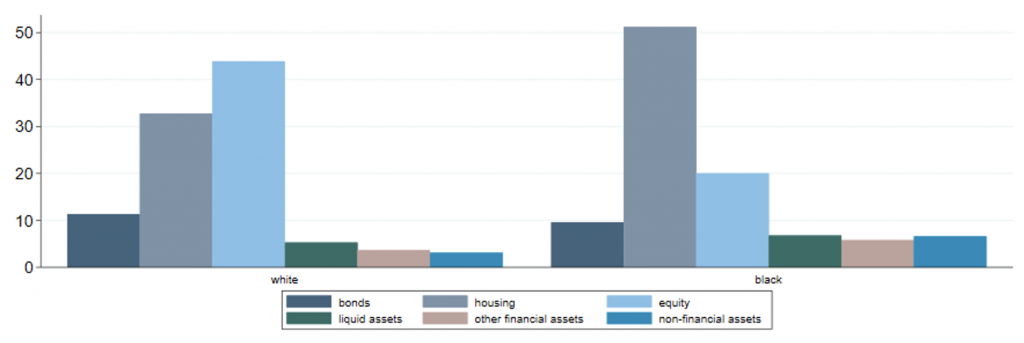

Yet at the same time, monetary policy has portfolio effects through its impact on asset prices. Asset price changes should affect the wealth distribution if portfolios differ systematically between black and white households, as is the case (Figure 1). Only a third of black households hold equity and less than half own a home. As a result, monetary policy that increases asset prices potentially has different effects on the portfolios of black and white households.

Figure 1 Portfolio composition (per cent of total for white and black households)

Much of the existing literature on the distributional consequences of monetary policy focuses on the income distribution, while the wealth distribution has largely been ignored because it was previously assumed that policy effects on asset prices were temporary. However, recent work suggests that these effects are persistent (Bernanke and Kuttner 2005, Paul 2020, Bernanke 2020, Cieslak and Vissing-Jorgensen 2020). The relative magnitudes of earnings and portfolio effects on the racial wealth and income gaps have not been explored in the literature.

Our new research (Bartscher et al. 2021) addresses this issue. We systematically examine the impact of a monetary policy expansion on the wealth of black and white households through the portfolio channel and on the gap between black and white income through the earnings channel. First, we estimate the impact of a policy shock on asset prices and the unemployment gap. Next, we use these estimates to examine the changes in wealth and income of the typical black and white household using data from the 2019 SCF to show how monetary policy affects the gaps. We find that although an expansionary monetary policy reduces the gap between black and white unemployment rates, it has only a small effect on the gap between average black and white earnings. At the same time, the policy expansion increases asset prices, resulting in capital gains which are orders of magnitude larger for white than for black households.

Monetary Policy, Asset Prices and the Unemployment Gap

To estimate the effects of a policy shock on asset prices, interest rates, and the unemployment gap, we use instrumental variables local projections following Stock and Watson (2018) and Jorda et al. (2020). Several exogenous policy shock measures are taken from the literature, including our benchmark series from Romer and Romer (2004) as updated by Coibon et al (2017).

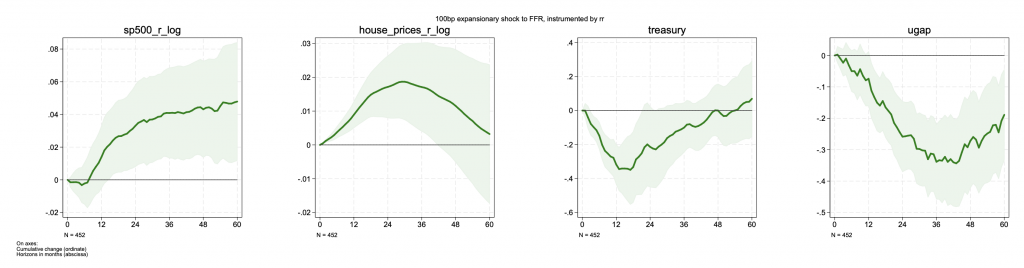

Figure 2 shows the effects of the monetary policy shock (a 100 basis point reduction in the federal funds rate) over a five-year period. Similar results are found with other shock measures. There is a substantial asset price boosting effect of surprise monetary easing, in combination with a reduction in the black–white unemployment gap. If white households profit disproportionately from such asset price increases, then it is possible that the portfolio effects of monetary easing go in the opposite direction of the income effects.

Figure 2 Effect of a monetary policy shock

Note: Effect of a 100-bps expansionary shock to federal funds rate on (from left to right): Stock prices (S&P 500), House prices (Case-Shiller Index), 10 year Treasury Bond rate and the gap between Black and White unemployment rates.

Earnings and Portfolio effects of Monetary Policy

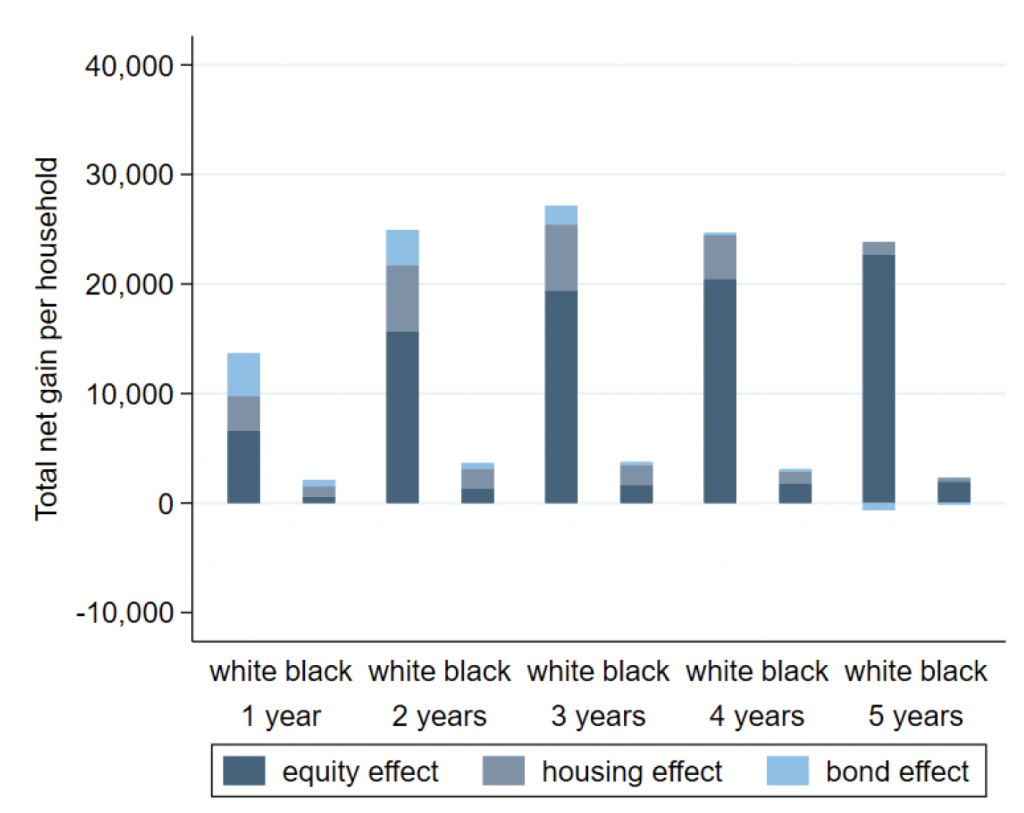

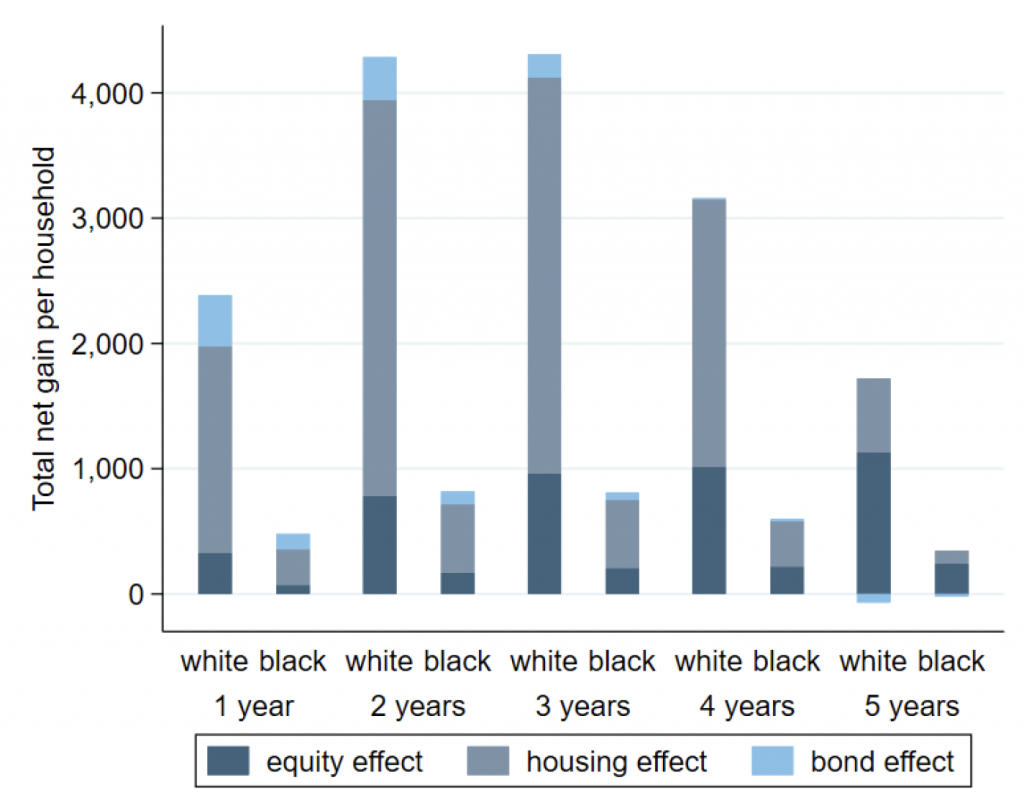

Based on our estimates of the asset price effects and the observed portfolio allocation, we derive the estimated effects of the monetary policy shock on wealth, which are shown in Figure 3. An unanticipated monetary policy accommodation leads to asset price changes that benefit white households to a much larger extent than black households because average white wealth is much larger, and a larger fraction is held in equities. The largest effects are after three years, reaching about $25,000 for white households and about one-fifth as much for black households. The biggest effect comes from the large and persistent effect on equity prices, while the house price effect diminishes over time. Bond effects are small because bond holdings are only a small fraction of total wealth for both black and white households.

Figure 3 Effect of a 100-bps monetary policy shock on wealth per household

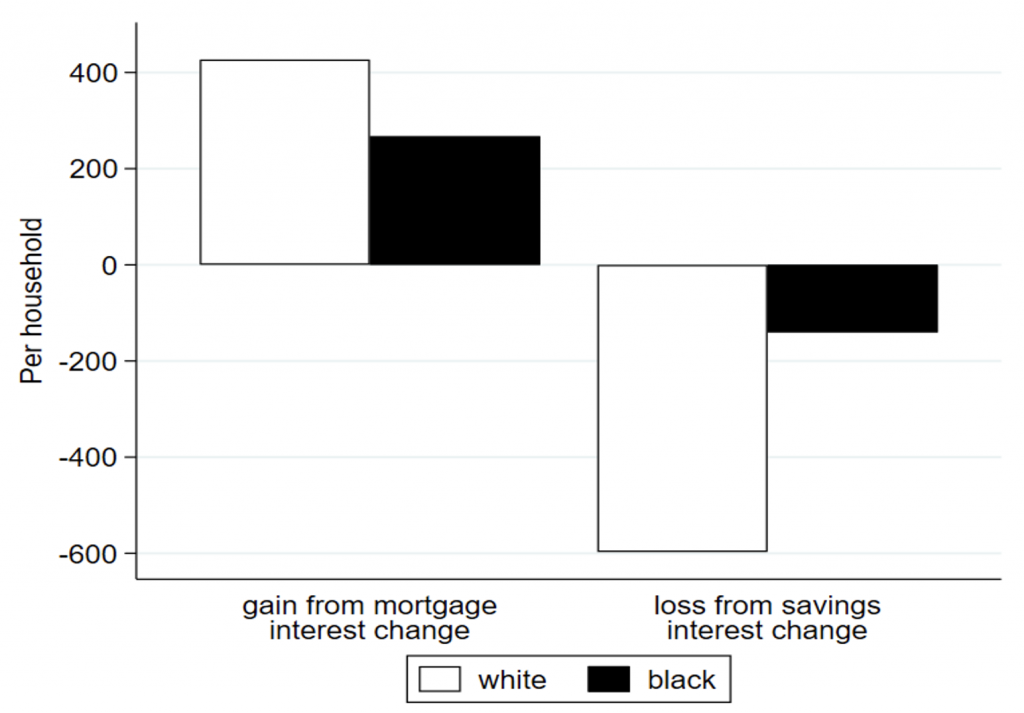

In addition to the portfolio effects, i.e. the direct effects of capital gains from the monetary shock, there are additional indirect effects of monetary policy shocks if an accommodative monetary shock reduces mortgage interest rates and the interest earned on deposit-type assets. Making assumptions on refinancing and passthrough to mortgage interest rates, we derive the mortgage interest and deposit rate effects from the monetary shock. These effects are shown in Figure 4. Interestingly, black households, with small deposit balances to begin with, lose little from lower interest rates; the average black household gains more from mortgage refinancing. White household deposit interest losses, almost $600, are higher than the average gains from refinancing.

Figure 4 Additional effects of a 100-bps monetary policy shock

Our estimates consider the effects of asset price changes on the wealth of the average black and white household. Since portfolio gains are highly concentrated among wealthy households, one may suspect that the racial wealth gap among more ‘typical’ households might be less affected by asset price changes. To examine this, we look at black and white households around the median of their respective wealth distributions (defined as households between the 40th and 60th percentiles). The portfolio effects of a monetary policy surprise on black and white households around the median are shown in Figure 5. Comparing the effects around the median to the average effects, we find that gains are smaller in levels but that the relative differences between black and white households persist.

Figure 5 Effect of a 100 basis point monetary policy shock on households around the median

Quantifying the Earnings Effect

The average gap between black and white unemployment rates has historically been about six percentage points. Our estimates show that the gap is reduced by a 100-bps monetary policy shock, with a peak effect after 3 years of -0.34 percentage points. We use earnings data from the 2019 SCF and some conservative assumptions to estimate the impact of the reduction in the unemployment gap on the earnings gap. Specifically, we assume that each black household head who finds employment receives the average earnings of employed black households. The additional income gains of the average black relative to white household is computed by multiplying the estimated impact of the monetary policy shock on the unemployment gap with the average earnings gain. The result is less than $100 per household, or just 0.19% of annual total income for all black households.

Finally, we compare the relative earnings effect to the relative portfolio effect defined as the difference in capital gains accruing to black and white households. The earnings effect of 0.19% of annual income after three years can be contrasted with the corresponding differential portfolio effect after three years of around 17% of annual income. Hence, the differential in the capital gains effect is orders of magnitude larger than the earnings effect.

Conclusion

Monetary policy shocks that change asset prices have differential effects on the wealth of black and white households. White households gain more because they have more financial wealth and hold portfolios that are more concentrated in interest-rate-sensitive assets such as equities. At the same time, monetary policy shocks reduce the gap between black and white unemployment rates and bring larger earnings gains for black households. Bringing the two together, however, leads to one stark finding: the reduction in the earnings gap pales in comparison to the effects on the wealth gap. Our analysis therefore does not bode well for the suggestion that a more accommodative monetary policy helps alleviate racial inequalities. Clearly, this does not mean that achieving racial equity should not be an important objective of economic policy, but the tools available to central banks might not be the right ones.

See original post for references

“hold portfolios that are more concentrated in interest-rate-sensitive assets such as equities”

There are many other assets (types) that are much more interest-rate-sensitive than equities.

Is it more that an ‘easy’ monetary policy likely leads to economic growth? (Ignoring possible later inflation issues.)

“Our analysis therefore does not bode well for the suggestion that a more accommodative monetary policy helps alleviate racial inequalities.”

Does our perception of wealth inequality lead us to institute changes that, however intuitive they seem, do nothing to change the fact that the nature of how wealth has already been distributed won’t change by mere percentages in compensation?

Furthermore, do our traditional ideas of what can help those trying to scale the socioeconomic ladder eventually solidify the current distribution of wealth?

Does Walter Benn Michaels have a point in our need to change our perception of the problem and the solutions offered to us?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uoBNBuYYgCA

I am asking purely to help me understand if my perception of where we are at is inherently delusional.

Climate change will demand ex-situ conservation. Very proper that the social carrying capacity on the Rio Magdalena exceeds and defies the notions of “experts” and thoughtful whitey in his pith helmet and monocle, feverishly working the bolt of his very gentlemanly Holland & Holland.

Or maybe we all just keep our cats inside?

Full time student here! Making a post for a class on “Stock Market or Economy” and I think this topic is not only fascinating, but applicable to both requirements.

The conclusion of the fact that the banks may not have the correct tools at their disposal is an interesting one for a number of reasons in my eyes. The banking system at its core- interest earned over time, etc., was originally adopted from predominantly Negro countries and cultures. We stole it. The white man eventually made it into what ew know today and then subjugated those that we stole it from; made laws to prevent them from being human enough to have the right to learn about the morphed system; systematically deprived them of generations of education, and then told them they were too dumb to learn it after warring for their God given freedom.

The property we also stole from the Natives gave the foundation for this issue. There was land O’ plenty after we killed everyone that it already belonged to. Now you have white men with free land, no debt and a white government to back them by making white-supporting rules.

None of this (albeit hypothetical statistics) division of wealth should shock even the minimally educated. It strikes me as odd that a white-majority-controlled banking system doesn’t have laws or protocols to diminish the wealth and equity gap between themselves and their African American counterpar… Get the joke yet?

I really enjoyed this post and commenting. I look forward to studying the topic further.

Yeah, you are right, it’s all white man’s fault.

In case they don’t teach you this in school, whites are only 10% of the world’s population and the only population group in decline (giving birth to only 7% of the world’s babies), yet are the most industrious and innovative people the world has known.

Whites unlocked the secrets of DNA and relativity, launched satellites, created automation, discovered electricity and nuclear energy, invented automobiles, aircraft, submarines, radio, television, computers, medicine, telephones, light bulbs, photography, and countless other technological miracles.

Whites were the first to circumnavigate the planet by ship, orbit it by spacecraft, walk on the moon, probe beyond the solar system, climb the highest peaks, reach both poles, exceed the sound barrier, descend to the oceans depths…and they built the most advanced society creating wellbeing and prosperity that you enjoy and to which you contributed nothing, yet.

You are correct, young grasshopper. Whites are very good at what they do and have done it very well.

And now a question, young grasshopper, . . . . . was any of it worth doing?

1. It’s almost like monetary policy isn’t a substitute for fiscal policy! :)–

2. Is there an easy way to think about whether/how this picture would be affected by very-long-run effects of shocks to the unemployment rate?

It doesn’t take charts and genius to realize that Bernanke and Yellen and Powell keeping ZIRP for 12+ years and counting, is creating a sociopathic elite that play politics and society, and even entire countries, for suckers…..but still, you know, ’tis what the founding fathers wanted (gasp!, shudder! shimmy! revere!)