Yves here. Jared Holst thought it was important to clarify the term “bullshit economy.”

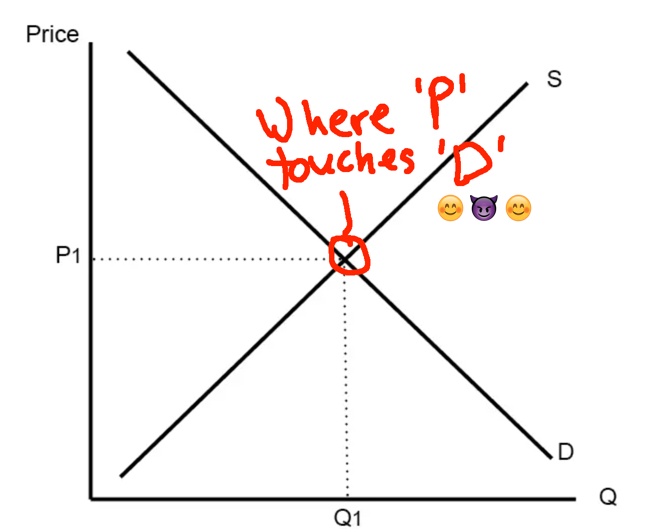

However, we’d like to add a key point: Jared relies upon the foundational chart of economics, the cute X of the downward sloping demand line and the upward sloping supply line that magically intersect and define a price.

We explained long form in ECONNED that this ain’t always so:

Consider the most basic image in economics: a chart with a downward sloping demand

curve and the upward sloping supply curve, the same sort found in Krugman’s diagram. Deidre McCloskey points out that the statistical attempts to prove the relationship have had mixed results. That is actually not surprising, since one can think of lower prices leading to more purchases (the obvious example of sales) but also higher prices leading to more demand. Price can be seen as a proxy for quality. A price that looks suspiciously low can produce a “something must be wrong with it” reaction. For instance, some luxury goods dealers, such as jewelers, have sometimes been able to move inventory that was not selling by increasing prices. Elevated prices may also elicit purchases when the customer expects them to rise even further. Recall that some people who bought houses near the peak felt they had to do so then or risk being priced out of the market. Some airline companies locked in the high oil prices of early 2008 fearing further price rises.The theoretical proof is also more limited than the simplified picture suggests. Demand curves are generally downward sloping, but in particular cases or regions, per the examples above, they may not be. Yet how often do you see a caveat added to models that use a simple declining line to represent the demand functions? Not only is it absent from popular presentations, it is seldom found in policy papers or in blogs written by and for economists.

McCloskey argues that economists actually rely on introspection, thought experiments, case examples, and “the lore of the marketplace,” to support the supply/demand model.

Similarly, a prediction of a simple supply-demand model is that if you increase minimum wages, you will increase unemployment. It’s the same picture we saw for the oil market, with different labels. In this case, the “excess inventory” would be people not able to find work.

One curious element of some of the responses was that they charged Card and Krueger with violating immutable laws of economics. For instance, Reed Garfield, the senior economist of the Joint Economic Committee, wrote:

The results of the study were extraordinary. Card and Krueger seemed to have discovered a refutation of the law of demand. Economists were stunned. Because of these extraordinary results, they debated the results. Many economists argued that the differences . . . were more than simply differences of minimum wage rates. Other economists argued that the study design was flawed.

Notice the assertion of the existence of “the law of demand,” by which Garfield means “demand curves slope downwardly,” when in fact no such “law” exists. And there are reasons the Card-Krueger findings could be plausible, the biggest being that the sort of places that hire low-wage labor may not be able to get by with fewer workers and still function.

Yet some empirical work by David Card, an economics professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and Alan Krueger, a professor of economics at Princeton, disputed the idea that increasing minimum wages lowers the number of jobs for the lowest-paid workers. Needless to say, the studies got a great deal of attention, with the reactions often breaking along ideological lines.

And there are cases where economists acknowledge that the demand line is not downward sloping, such as when demand is inelastic:

“People’s lives are not commodities…you cannot ask the question how much will you pay to live, because the answer is everything.

That is what makes the price of medicine different than the price of an iPhone.” – @AOC pic.twitter.com/j4DTOR7VgI

— SocialSecurityWorks (@SSWorks) May 16, 2019

Mind you, I’m not disputing Jared’s argument below, since the simple X picture is often accurate. It’s just every time I see that classic demand/supply chart, I feel I have to clear my throat.

Jared’s commentary about bonnet-owners and the rancid ecosystem that develops to exploit them is reminiscent of another passage in ECONNED:

It is easy to be overwhelmed by the vast panorama of financial instruments and strategies that have grown up (and blown up), in recent years. But the complexity of these transactions and securities is all part of a relentless trend: toward greater and greater leverage, and greater opacity.

The dirty secret of the credit crisis is that the relentless pursuit of “innovation” meant there was virtually no equity, no cushion for losses anywhere behind the massive creation of risky debt. Arcane, illiquid securities were rated superduper AAA and, with their true risks misunderstood and masked, required only minuscule reserves. Their illiquidity and complexity also meant their accounting value could be finessed. The same instruments, their intricacies overlooked, would soon become raw material for more leverage as they became accepted as collateral for further borrowing, whether via commercial paper or repos.

But even then, the bankers still needed real assets, real borrowers. Investment bankers screamed at mortgage lenders to find them more product, and still, it was not enough.

But credit default swaps solved this problem. Once a CDS on low-grade subprime was sufficiently liquid, synthetic borrowers could stand in the place of subprime borrowers, paying when the borrowers paid and winning a reward when real borrowers could pay no longer. The buyers of CDS were synthetic borrowers that made synthetic CDOs possible. With CDS, supply was no longer bound by earthly constraints on the number of subprime borrowers, but could ascend skyward, as long as there were short sellers willing to be synthetic borrowers and insurers who, tempted by fees, would volunteer to be synthetic lenders, standing atop their own edifice of risks, oblivious to its precariousness.

Institution after institution was bled dry. Yet economists and central bankers applauded the wondrous innovations, seeing increased liquidity and more efficient loan intermedation, ignoring the unhealthy condition of the industry.

The firms that had been silently drained of capital and tied together in shadowy counterparty links teetered, fell, and looked certain to perish. There was one last capital reserve to tap, U.S. taxpayers, to revive the financial system and make the innovators whole. Widespread anger turned into sullen resignation as the public realized its opposition to the looting was futile.

The authorities now claim they will find ways to solve the problems of opacity, leverage, and moral hazard.

But opacity, leverage, and moral hazard are not accidental byproducts of otherwise salutary innovations; they are the direct intent of the innovations. No one at the major capital markets firms was celebrated for creating markets to connect borrowers and savers transparently and with low risk. After all, efficient markets produce minimal profits. They were instead rewarded for making sure no one, the regulators, the press, the community at large, could see and understand what they were doing.

Forgive this very long-winded set-up to Jared’s somewhat light-hearted illustration of the bullshit economy at work. Businessmen once sought to gain advantage by creating a competitive advantage, which in the past generally meant finding a way to serve customers better or at lower cost. “Serving them better” might mean catering to niche needs, like having a convenience store open 24 hours where the patrons accepted high prices because the store’s location and hours were worth paying for. Too often now schemes for gaining advantage rely on exploiting customer ignorance or desperation, or using legal and regulatory process to restrict their choices.

By Jared Holst, the author at Brands Mean a Lot, a weekly commentary on the ways branding impacts our lives. Each week, he explores contradictions within the way politics, products, and pop-culture are branded for us, offering insight on what’s really being said. You can follow Jared on Twitter @jarholst. Originally published at Brands Mean a Lot

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our necessities but of their advantages. — Adam Smith, The Wealth Of Nations.

Economics, the sort which most people study in high school and undergrad, teach us that if demand exists for a good (good, in this essay, can mean a product or service), supply will rise to meet that demand. Conversely, if demand falls, so too will supply. This function is meant to illustrate the relationship between buyers and suppliers—market equilibrium is when demand and supply equal one another, signaling that suppliers and buyers agree, sans coercion, on a price and a supply of a good.

The price of a product also plays a role. If a product’s price is too high, the supply of the product will outstrip the demand, creating a surplus. Priced too low, and the demand outstrips the supply, creating a shortage.

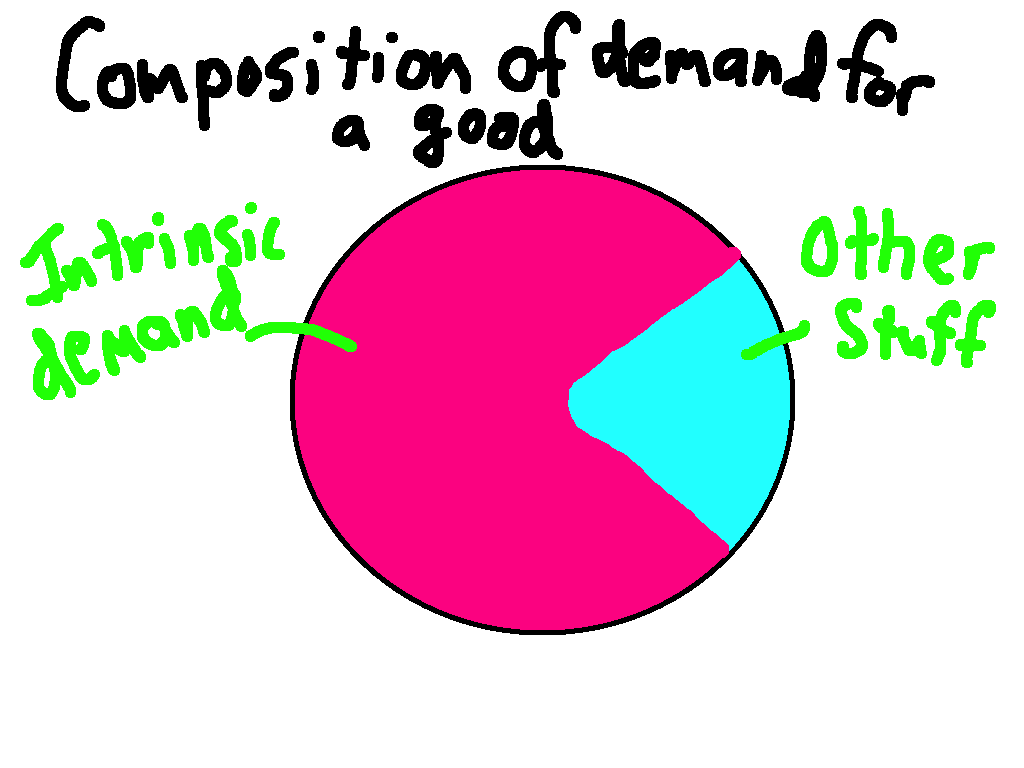

But in foundational economics, virtually no time is spent on the creation of demand.

The origin of the demand for a particular good is central to The Bullshit Economy. In our high school and undergrad economics, we’re taught to think of market equilibrium in terms of staple goods like gasoline and plumbing and discretionary goods like PlayStations and first class airfare. People need gas because it powers combustion motors and they want first class airfare because of comped bloody marys and wide seats. Although external forces impact the demand of each—an OPEC embargo in the case of gas or a recession in the case of first class flying—most of the demand for those goods is intrinsic to the good itself. The supply and the goods themselves are generated to meet demand.

At the root of The Bullshit Economy is artificial demand. Demand that precedes supply. Market equilibrium, rather than an unfettered and unspoken agreement on terms between buyers and suppliers, becomes coercion on behalf of buyers.

You possess a priceless family heirloom, an embroidered lace bonnet worn by 6 successive generations. It’s traveled from the grey skied, hardscrabble motherland, to the shores of America, all the way to your attic. Through Facebook, you happen upon a vast community of others in possession of priceless antique bonnets. The community numbers millions.

Sensing opportunity, an interloper makes their way into the community. The rapscallion invents a unique jelly that permanently stains the antique bonnets. At that years’ Antique Bonnet convention in Springfield, MO, they manage to stain millions of heirloom bonnets. Being unique, this jelly’s resistant to all existing stain removers. The only solution? A patented jelly remover, invented by the rapscallion.

Knowing they’ve got the market cornered and control the supply of jelly remover, the rapscallion charges obscenely high prices for the product. They recruit companies, who in partnership with the rapscallion, conjure financial products to help those with stained bonnets afford the jelly. Those with stained bonnets have two options, pay the price, or go without a pristine bonnet, thereby angering the ghosts of generations past and forgoing spotless headwear for future generations.

Pictured: Adam Smith in a bonnet

The government gets hip to it all and rules that Rapscallion® brand jelly remover has created a monopoly for itself and must share its recipe so that other jelly remover brands may enter the market. Towards the financing products created to make jelly remover affordable, both public and political sentiment sours. New laws are written that expressly outlaw the extension of certain types of jelly remover loans and cap the rates at which the remaining, legal loans can be given.

Knowing that jelly remover is vital to antique bonnet owners, other companies produce their own removers, but prices remain high due to unspoken acknowledgement by jelly remover producers of the crucial nature of jelly remover. A jelly remover cartel forms.

Noticing loopholes in the government’s ruling, new firms step in to help bonnet owners pay for the product. Instead of calling them loans and charging interest, they brand them ‘fiscal favors’. Receiving a fiscal favor requires bonnet owners to provide their bank routing and account numbers so the new entrants may provide an initial deposit into the users’ accounts…and subsequently garnish a portion of the users’ paycheck for the next 10 years. The garnishing rate shall never be less than 45% and increases from there depending on the lunar phase of the users’ payday.

Illuminated by fluorescent tube lights, lawyers examine government regulation to stay on the right side of the law and draft consumer-side terms and conditions to be agreed upon via browser checkbox. Advertising agencies staffed with lit majors from universities like Bennington, Bard, and Yale pitch these companies on which non-binary colorway will appeal to the stained bonnet cohort. Product managers fresh out of MIT and Harvard Business School ingeniously work dark patterns into each new app so as to befuddle bonnet owners into agreeing to pay more as each month passes.

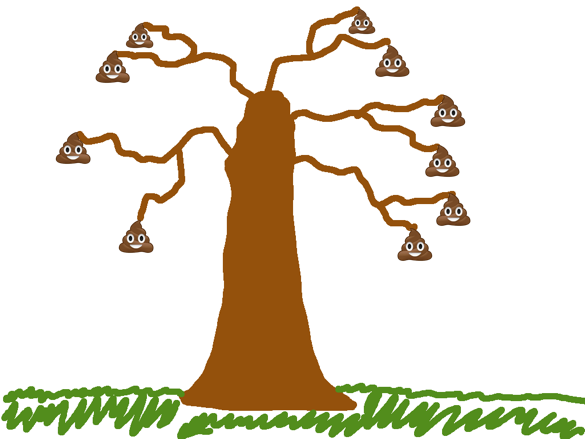

It’s a shit seed, from which sprouts a shit tree, which bears shit fruit. It stinks!

Some will read this and say, “Isn’t it good that now the bonnet people can afford the cleaner for which they so desperately yearn?” Couldn’t the bonnet people just put it on a credit card, that must be better? The average credit card APR is 15.56% to 22.87%. Also, in a properly functioning economy and society, there’d be no need for these companies in the first place. The genesis of the demand is rotten.

Not every good in the bullshit economy follows this exact pattern, but many occupy a portion of the story. Uber and Lyft, for example, thrive because of loopholes in the law around what constitutes an employee versus an independent contractor. The college admissions ecosystem perpetuates because, amongst other reasons, inequality of opportunity and access.

In the coming months, I aim to expand on this by way of presenting fresh examples. In the meantime, I hope this helped narrow in on the source of the stench.

Definitely time to reread ECONNED. Adam Smith and David Hume too. Got them all out on the coffee table in my study now. The goal of real economics has always been victory over bullshit, or, to put it more politely, freedom from rents and monopolies.

And here is Edward Gibbon on the bullshit of monopolies (he is reflecting in his Memoirs on his unproductive fifteen months at Magdalen College in 1752-1753): “The legal incorporation of these societies [the Oxbridge colleges] by the charters of popes and kings had given them a monopoly of the public instruction; and the spirit of monopolists is narrow, lazy, and oppressive; their work is more costly and less productive than that of independent artists; and the new improvements so eagerly grasped by the competition of freedom, are admitted with slow and sullen reluctance in those proud corporations, above the fear of a rival, and below the confession of an error. We may scarcely hope that any reformation will be a voluntary act….”

“…and the spirit of monopolists is narrow, lazy, and oppressive…:

That thought is especially worthy of emphasis.

What is this “real economics” of which you speak, and where is it practiced?

Or is this like the discourse between Leninists and Trotskyists and all the various flavors of Marxists, up to and including Groucho?

One other reading recommendation: Steve Keen’s Debunking Economics: The Naked Emperor Dethroned. ECONNED is certainly worthwhile, but Keen really lays an awful lot of bullsh*t to rest. For example, Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu mathematically proved you can’t believe the Adam Smith supply/demand stuff. It’s mathematically impossible. It’s as true as 2+2=5. In other words, never.

When I was a kid, it was an article of faith that a high price signaled high quality. “You get what you pay for.” That has had declining truth value ever since. It’s surprising there are still people who believe it.

I remember one of the corrupt city officials of Bell, California asserting this to justify their extremely high salary.

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/City_of_Bell_scandal

“Spaccia concurred, saying: “I would have to argue you get what you pay for.” ”

And I doubt if anyone in the Los Angeles area believed it about the overpaid Bell officials.

But one can suggest that higher education in the USA has recently implied “you get what you pay for” applies to their college degree product.

I know nothing about Bell officials in CA but you are assuming from the very beginning they are overpaid. I would argue that it is true that many always think that some others, except themselves, are overpaid while one (possibly) never thinks to be overpaid herself or himself. It is quite a subjective theme unless you provide with some kind of job valuation scheme and, even then, probably very much disputable with lots of subjective arguments about ‘value’.

The link I provided has the quote “revealing that the city officials of Bell received salaries that were reported as the highest in the nation”

Also

“Rizzo was sentenced to twelve years’ imprisonment for his role in Bell and to 33 months’ imprisonment in a separate income tax evasion case. Spaccia was sentenced to eleven years and eight months’ imprisonment. Both were also ordered to repay millions of dollars in restitution.”

Here is another link and quote:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bell,_California

“City residents voted to become a charter city in a special municipal election on November 29, 2005. Fewer than 400 voters turned out for that special election. More than half of those votes were dubiously obtained absentee votes. Being a charter city meant that city officials were exempt from state salary caps. A scandal ensued, in which several city officials were indicted for giving themselves extraordinarily high salaries.”

I am still comfortable asserting that Bell city officials were overpaid (“extraordinarily high salaries”.)

I don’t remember “assuming from the very beginning they were overpaid” as the events were reported in the press.

The facts of the scandal indicated to me that they were overpaid for their tasks when compared to other city officials in the USA.

I do not believe there is much logic to how much people are paid. I know I was grossly overpaid for the work I did, given how little my work — good work I believe — was used or valued. I served as a conduit for channeling US Government money into the pockets of the contracting firm that employed me. Beyond that, neither my work nor I were valued. To my best knowledge, the only reason I received the ‘cut’ from the take that I received was the result of Government regulations intended — I believe — to suggest I had value and shared in the arrangement, which I did, but also to avoid embarassing the firm that employed me. The idea was to convey a sense that my labor had value and the firm took only a ‘fair’ part of fees charged to government for delivering my services. I was overpaid — and even so I cannot claim to have lived a life of abundance, or life of leisure until my retirement. But the partners of the firm that employed me were not ‘overpaid’ in any ordinary sense of that word. I suspect John Wright’s Bell City officials were probably overpaid in the same sense that the partners of my firm or the upper management of many Corporations are ‘overpaid’. I believe there are magnitudes of difference that undermine any job valuation schemes or subjective arguments about ‘value’.

In short, I both agree with your point about the subjectivity of how much people are paid, and disagree with its applicability after a certain level of pay — purely subjective — when other considerations apply.

Also high price induces fewer sales with higher associated status. Hence the protection of perfume markets from gray imports.

Not sure, but you might need to credit Jim Lahey for the shit tree analogy.

Extrapolating, private equity are in the business of farming *family blog* tree orchards.

Author here: Jim Lahey is exactly who I was thinking of when it came to the shit tree. Did he actually say ‘shit tree’ though? I can’t remember…If so, I’ll absolutely need to go add credit where it’s due.

Thanks for picking up the reference!

In a previous comment I noted that the stock market is at this point dislocated from the actual American economy. Otherwise how could it be that the stock market keeps on climbing while most people are doing it tough and businesses dying by the thousands. I think that the same applies here in that prices are also suffering a disconnect from actual value and that this has been going on for a very long time.

So as an example I will use everybody’s love/hate and by that I mean the price of gold (the same appears to be happening with the price of silver). So here is Sir Eddie George, Governor Bank of England in conversation with Nicholas J. Morrell –

‘We looked into the abyss if the gold price rose further. A further rise would have taken down one or several trading houses, which might have taken down all the rest in their wake. Therefore at any price, at any cost, the central banks had to quell the gold price, manage it. It was very difficult to get the gold price under control but we have now succeeded. The US Fed was very active in getting the gold price down. So was the U.K.’

And this conversation took place over twenty years ago. Think that anything has changed? And does anybody remember the LIBOR Scandal from a decade ago? Thing is, for capitalism to work you have to have relatively honest price signals so that decisions can be made. Price discovery is vital here. And when you don’t, you have all these parasites coming out of the woodwork as talked about in this article.

“In a previous comment I noted that the stock market is at this point dislocated from the actual American economy. Otherwise how could it be that the stock market keeps on climbing while most people are doing it tough and businesses dying by the thousands….”

The financial rags proclaimed from the mountain top in late spring and summer last year that despite the record unempolyment, riots in the streets, a raging pandemic, disrupted supply chains, and millions on the edge of eviction that the market is forward looking. The Fed has your back.

So with the logic of “the devil made me do it” many speculators took out more leverage and/or bought at whatever stock price. So the mantras has been: “You know, like, it’s not my fault.The Fed made me do it because the Fed had a wrong-headed policy meant to spur productive investment that could be manipulated.” (Something to that effect).

Now, apparently “the market” has special forward looking lenses that are rose tinted. Any future bad news is glossed over and really the only time they will mention the bad news is as if it’s past tense with the caveat the past performance does not guarantee future results.

$814 billion has been borrowed by people investing in the stock market, borrowed against their portfolios. That’s a 49 percent increase over last year. And that’s not counting the largest banks are not actually reporting all margin debt that is fueling the sharp rise in stock prices.

Fascinating how the price of gold seems disconnected from inflation these days. (Real inflation, as opposed to the BS stats that the gubmint puts out.)

The http://www.shadowstats.com site has a better take on inflation numbers as they calculate it the way the government once did prior to 1995. “March 2021 annual Consumer Price Index inflation hit an unadjusted three-year high of 2.62%, as gasoline prices soared to multi-year highs, not seen since well before the 2020 Oil Price War.” According to the site real inflation is around 6%. It’s obvious to anyone who shops for groceries that prices continue to go up (while the packages get smaller), and then there are housing prices, stock prices etc. Gold remains very controlled.

I did my best at reading this excellent post. I wonder where unicorn startups fit into the BS economy. Any dude with an idea thinks it’s worth developing–is this just another place to throw money? Most of these don’t seem to arise from a universal need, and they don’t seem to require proven integrity all of the time (e.g. Thanos).

Among the start up types that make my BS detector readings go haywire are the “innovators” of yet another way to pay for something. (FINTECH…it may be called). Skimming for profits. It’s a branch of rentierism.

And right on cue:

https://www.marketwatch.com/story/the-new-tv-show-unicorn-hunters-will-feature-steve-wozniak-and-allow-viewers-to-invest-in-ipos-11618334384?mod=mw_latestnews/

The series will spotlight up-and-coming growth companies looking to hit the $1 billion ‘unicorn’ valuation …

(BS is RELENTLESS)

I wish to add something based on my memory of reading John Kenneth Galbraith many years ago. [I do hope that a scholar of Institutional Economics will weigh in here.]

One reason why economics professors in the U.S. willl not teach lessons from Professor Galbraith’s works, books that used to be on the best-seller lists in the 1950s – 1970s, is that Professor Galbraith produced empirically detailed conclusions – theories, really – that neoclassical economists safely ensconced at universities and colleges cannot answer. I believe it was his book The New Industrial State that helped in no small way to obliterate the neoclassicals’ “Law” of Demand. In that book, Professor Galbraith shows how much effort giant corporations went through in order to research, develop, test, refine, test again, and finally bring to market new products. Thus, as the late [great] Institutionalist Robert E. Prasch taught me, these corporations don’t just sit back and take the Demand curve as “given”; they will have spent far too much time, effort, risk, and money to bring such a complicated new product to market. Hence the vast resources devoted to Marketing departments.

In terms of economic theory, corporations – after putting so much effort and so many resources into new products – spend vast sums on marketing & sales to push the Demand curve further and further out. They don’t accept a static Demand curve. And, given the resources of Detroit and U.S. Steel (to name but a few) back in the 1950s and 1960s, those corporations certainly could employ the resources to keep the Demand curve from resting on its laurels.

Let me please reiterate: I hope that a practicing Insitutional economists, or three, will weigh in here; my memory and authority are pretty much those of a lay person.

Quite true. And much of the time variations in the quality/features of a good or service are not the result of inherit demand preferences by discriminating consumers, but carefully marketed gradations designed to increase overall profit margins. Potential supply (as in, we can produce this) creates demand.

Advertising is exogenous to Economic theory.

Black Queen: “With a smile on your face everything will seem brighter because from now on we are… what?”

Black Queen’s Guard: “Uh, not at home to Mr. Grumpy, your majesty.”

“Free Market” ideology, as it is constituted, is not something that any actual business engaged in industrial production would allow themselves to be subject to for a minute, much less the time it took to get products on shelves and so on.

likely even farmers would have problems with it.

beyond basic needs, isn’t every demand “created”?

Advertising generated demand was also one of the main ideas in his “The Affluent Society”. It’s a sad commentary on the times that back then, the advertising was done to keep the factory’s humming (“production” being the societal goal after the depression), where now the factories are dumped like hot potatoes, but the marketing becomes the new corporate ‘core competency’.

Pretty clear there are at least two economies in the Empire. Mopes seem ok with the notion that it’s a single continuum, bottom to top, and one can graph wealth vs population very neatly and pretty close to asymptotically, so visually it seems to compute. I visualize the division as a gasbag dirigible linked by a vacuum hose to Planet Earth, sucking up sustenance and wealth and dumping excreta down on the mopes, lots of whom aspire to join the Excretory Class by some fortuitous inspiration. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2019/09/10/america-has-two-economies-and-theyre-diverging-fast/

Your description reminds me of the movie “Elysium,” where the elite live in a clean, organic space station with all the latest technology while the mopes toil and die down on Earth. I believe we’re both describing our future (and our present)….

Instead, Econ profs made JKG a punchline – “All great economists are tall. There are two exceptions to the rule: Milton Friedman and John Kenneth Galbraith.”

As told to an Ivy League graduate Econ class in the 1980s by a soon to become household name.

I’m not worried, and neither should you be, somecallmetim: neo-classical economists will become, owing to their academic defense of austerity and neoliberalism, the new punchline, while most likely John Kenneth Galbraith will be read, discussed, remembered, and praised for a long, long time.

“People’s lives are not commodities…you cannot ask the question how much will you pay to live, because the answer is everything.”

The above is something true for most, but not all individuals. It is also something that at some point doesn’t work for society.

AOC makes a rookie mistake in her understanding of economics, by failing to realize that “demand” does not simply mean that a person wants something (or even requires it for survival). I made this same mistake during one of my undergrad micro-econ courses and was mocked by the professor for being so dense. You see, in economics “demand” is actually shorthand for “effective demand,” i.e. the desire to purchase a thing combined with the ability to do so. So, if the poors cannot afford some pharmaceutical product then they do not actually have a “demand” for it, and you can’t blame the pharma companies for not filling a demand that doesn’t exist. There is no problem with our healthcare system not filling the demand for healthcare, because only those who can pay the price for healthcare (whatever that happens to be) actually have a demand for it, QED. This is the same reason why homeless people do not create any demand for housing, despite what the uninstructed might assume. It all makes sense, if you think about it long enough…and you’re a bit of a psychopath…

So there is no place for “fulfillment of existing needs” in economics. Yeah, I’m stupid. But, whatever makes it easier for TPTB to steamroll over the general public.

“you can’t blame the pharma companies for not filling a demand that doesn’t exist. ”

I’d say your mocking micro-econ prof was a total psychopath.

Ding, ding, ding! In case it wasn’t apparent, I do not have any use for the mainstream economists use-and-abuse of the concept of demand.

Economics is indeed dismal. I fear my “effective demand” is increasingly ineffectual and I am not yet homeless, starving, or sick. Does anyone else share my fears? Ding, ding, ding! Me too!

I thought we did this already, but without invoking George Soros here goes:

Exchanges do not happen in one direction only: I demand carrots from my farmer, and I also supply him with money. He demands money and supplies me with carrots .We are both better off at the end of the deal: or there would be no deal in the first place.

I always said that if Bill Gates ever came up to my table at market, I would have a special price just for him.–Fairness is not everyone pays the same, but what everyone can afford…

I take your point about fairness and agree. But on the practical side — I hope you have some kind of agreement with other tables about what particular buyers should afford.

Why in god’s name, would she use an iPhone? Fairphone 3 you can rebuild, yourself. I couldn’t buy stock in Huawei, since I’m not an employee. HTC, is pretty much dead, from offering too much value; to sustain their union employees. Even LG workers have a tiny say in sourcing? Do YOU still have that old Nokia? If she’d bought a cheap Pixel 4a, the Kapital Kops Cosplay Coup might’ve been lots less scary?

I am sure she didn’t buy that phone, it was bought by Congress and provided to her. Congresscritters and staffers have a phone for official business and a phone for personal use. They need to separate church and state. And if she has an iPhone provided by Congress, it’s a huge cognitive and practical pain to work with a different OS on your private phone.

In addition, she’d spend more in all the tech setup and babying than she’s save. Mere mortals don’t like having to supervise tech people to implement non-mainstream solutions, particularly since….drumroll….she’d have more limited choices in who she could hire to help her. And she has security issues.

I expect I will have to eventually switch to Linux and I dread the day because it will cost me a small fortune in tech consultant time for me to transition. I will most assuredly come out behind financially.

It should be noted that Adam Smith vehemently opposed rentiers, like landlords and patent holders.

Michael Hudson has written brilliantly and extensively on that point, adding criticisms by Marx. I believe the US patents and patent rights systems are at the point where even valid patent claims can be crushed in a wave of law suits by deep-pocketed holders of wrap-around and nuisance patents. IBM was famous for using a strategy of dipping into its deep pockets to quash valid claims from less well-healed patent holders. My own biases toward the value of patents were formed by the Xerox versus IBM patent suit that resulted in the relatively tiny damages awarded to Xerox. I do not know much of the particulars of the case, but I have long held the Xerox patent disclosures in very high regard. The basic Xerox patent is very beautiful to me.

I use Yves’s mention of “Econned” and her extensive references to it to comment on an issue peripheral to the topic of this post. I am sad to report what happened to the copy of “Econned” I hoped and expected might find a place on the shelves of my local library. Yves let me take a copy of “Econned” at the going away party she hosted at her apartment in NYC — a party I very greatly enjoyed and recall fondly. I promised to give the book she entrusted to me to my local library — and did.

Later, I found “Econned” at the back of a cart of books placed near the entrance to the library for purchase by purchaser election or not of making a small contribution to the library. Shelve space is limited … but not that limited. I recovered and still have the book. I have not returned to or contributed to the town library since I recovered “Econned”. I am not proud of withdrawing my small support of my town library nor would I recommend any but the fullest support to town libraries. I was and remain angry whether my anger is rational or not.

I fear the bonds of ‘right thinking’ extend very far down. I became aware of another gross failing of the town library when I looked for books on basic chemistry, and then looked for books on science and mathematics in general, and on technology. Even the regional library in the richer county next door was bereft of books on science, mathematics, or technology. It is difficult for me to characterize what books either library held.

Rabbit holes abound here … :)

If we were to follow them all, what interesting discourse would multiply many fold.

A dash of Say’s Law to start, a twist toward Veblen’s Conspicuous Consumption to follow … and all wrapped up in the contemporary psychology of consumerism and delivered in a box of neo-liberal wage depression … which brings me to my #Nitpick:

Uber and Lyft, for example, thrive because of loopholes in the law around what constitutes an employee versus an independent contractor.

IMO Uber and Lyft thrive because of wage depression.

All human societies basically have the same function.

To produce the goods and services that society needs.

Any surplus can be shared out within that society, usually very unevenly.

Capitalism is about capital accumulation?

Money is just an instrument for carrying out transactions within that society; its value comes from what it can buy.

You don’t really want people hoarding the stuff, although this is what usually happens.

You want that money to circulate within the economy.

Weimar Germany and Zimbabwe were never short of money.

Weimar Germany and Zimbabwe had created far too much money compared to the goods and services available within the economy causing hyper-inflation.

States can just create money, and the last thing you want is too much of the damn stuff in your economy.

They had made so much money it lost nearly all its value, and they needed wheelbarrows of the stuff to buy anything.

Money has no intrinsic value; it comes from what it can buy.

Central bankers actually look at the money supply, and expect it to rise in line with the new goods and services in the economy, as it grows. More goods and services in the economy require more money in the economy.

Paul Ryan was a typically confused neoliberal and Alan Greenspan had to put him straight.

Paul Ryan was worried about how the Government would pay for pensions.

Alan Greenspan told Paul Ryan the Government can create all the money it wants, there is no need to save for pensions.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DNCZHAQnfGU

What matters is whether the goods and services are there for them to buy with that money.

That’s where the real wealth in the economy lies.

State can create money out of nothing.

Private banks can create money out of nothing.

You don’t need wealthy investors; the banks should be lending the money they create into business and industry. It comes out of nothing, there is no real limit.

That money will then create real wealth, which lies in new goods and services in the economy.

Banks – What is the idea?

The idea is that banks lend into business and industry to increase the productive capacity of the economy.

Business and industry don’t have to wait until they have the money to expand. They can borrow the money and use it to expand today, and then pay that money back in the future.

The economy can then grow more rapidly than it would without banks.

Debt grows with GDP and there are no problems

The banks create money and use it to create real wealth

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

All human societies basically have the same function.

To produce the goods and services that society needs.

Capitalism is the same, even though we now think otherwise.

“Let’s wait till the next time a particularly virulent flu comes around, then use our control of media and the intelligentsia’s loathing of the president to rake in billions from a flu vaccine that only old people lined up for before.” The implications of Mr Holst’s analysis are very clear. Yet folks go on trusting a proven grifter like Fauci as though he were Buddha.

I forget who said that, in mainstream economics, a “law” is a plausible thing that’s probably not true; a “hypothesis” is a crazy thing that’s definitely not true.

Examples. 1. Downward sloping demand curves, rising marginal cost of production; 2. Efficient Markets, Ricardian Equivalence, Expansionary Austerity