Yves here. Identifying the various mechanisms by which the rich pass their advantages to their offspring is an important line of inquiry. However, perhaps because it is hard to parse out for analytical purposes, one advantage of growing up in a wealthy household is acquiring class markers. For the British, it’s the posh accents (particularly the ones acquired at public schools) as well as learning skills that are typically expensive to acquire, like riding horses and skiing, or in the US, sailing (the exceptions for people of modest means are living in communities where those are routine activities, so for skiing, living in a mountainous areas, or in a place like New Zealand, where many middle class families sail). In America, another class marker that few members of the PMC seem to have mastered is the easy affability and beautiful manners of those who come from East Coast old money families.

By Sreevidya Ayyar, Research Assistant, University College London; Uta Bolt, PhD candidate, University College London; Eric French, Professor of Economics, University College London; Co-Director, the ESRC Centre for the Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy (CPP) at IFS; Jamie Hentall MacCuish; PhD researcher, University College London; and Cormac O’Dea, Assistant Professor in Economics, Yale University. Originally published at VoxEU

The children of rich families tend to go to better quality schools, have higher cognitive skills, and complete more years of schooling. This column exploits unique data from the National Child Development study to determine these early childhood factors go on to have long-run impacts on an individual’s lifetime earnings, perpetuating a cycle of wealth. These results suggest that policies that equalise investments, such as improving school quality, could promote income mobility.

Rich parents have rich children. Why is that the case?

The children of rich families tend to differ from their poorer peers in multiple ways. They have fewer siblings and more educated parents. Their parents spend more time with them and send them to better quality schools. Their cognitive skills are higher, and they complete more years of schooling. All of these channels have been found to affect an individual’s earnings (Blanden et al. 2007, Keane and Wolpin 2001, Cunha and Heckman 2008, Daruich and Kozlowski 2020). However, in order to design policies to improve intergenerational mobility, we need to understand how these channels interact with each other in generating correlations in lifetime income across generations.

Take the example of school quality. Attending a high-quality school may have direct long-run effects on an individual’s lifetime earnings by creating a more valuable professional network, for example. However, attending a higher quality school can also have indirect effects on lifetime earnings through improved cognitive skills and/or the student staying in education for longer. Each of these channels are more likely to benefit the kids of richer parents, who tend to have access to better schools. In a new paper (Bolt et al. 2021a), we use mediation analysis to quantify the different channels through which parental income can impact an individual’s lifetime income. We find that intergenerational earnings persistence is mainly explained by differences in investments received during childhood, which in turn drive differences in cognition, years spent in education, and ultimately lifetime earnings.

We exploit unique data from the National Child Development Study (NCDS), which initially surveyed families of the entire population of children born in one particular week in 1958 and has followed them up until today. The NCDS contains rich information on: family income and circumstances during childhood, indicators of quality time that parents spent with the children, proxies for the quality of schools that they attended, measures of cognitive skills, as well as final educational outcomes and earnings throughout the lifecycle.

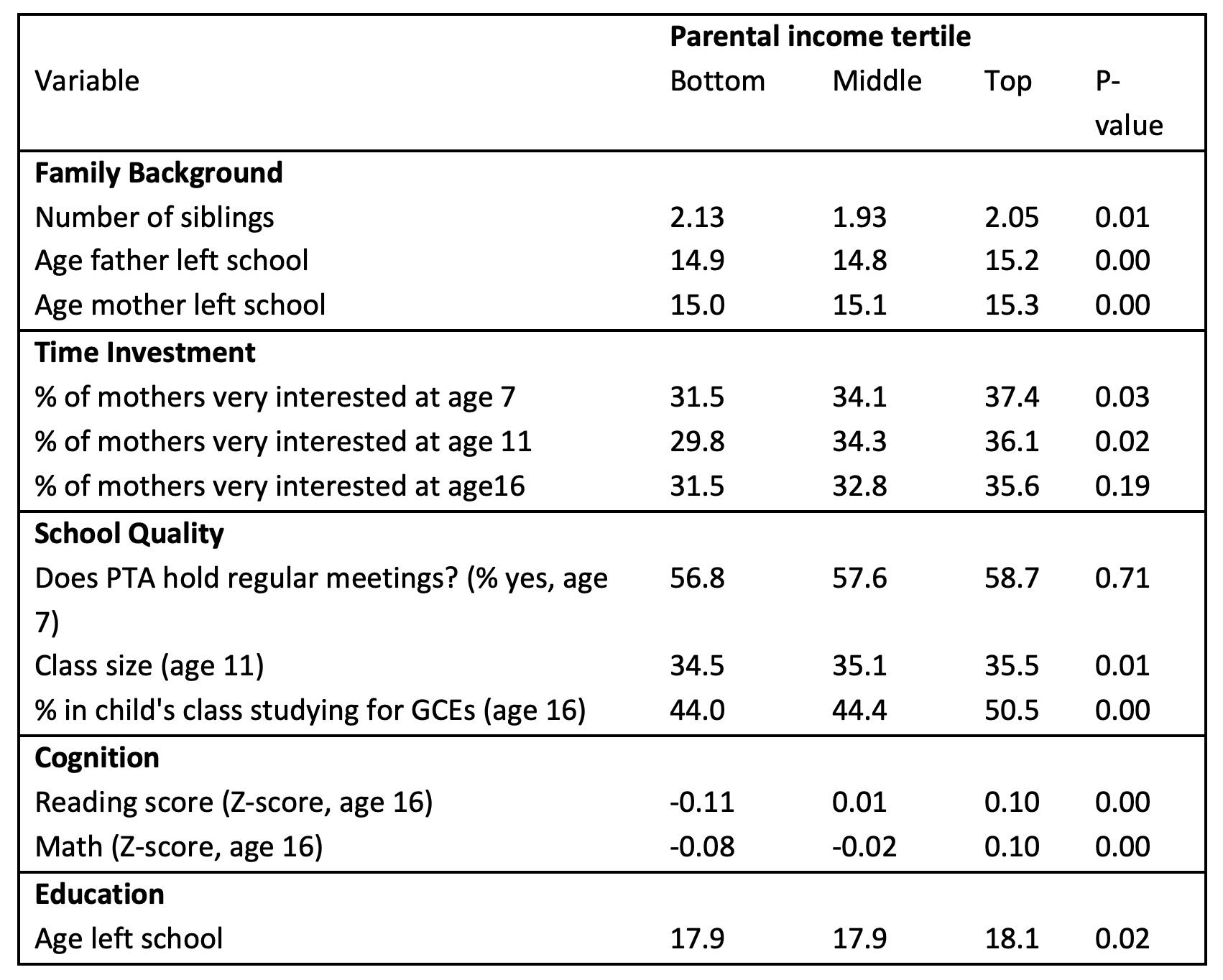

Table 1 shows gradients for some of our channels of interest by parental income tertile. The table shows that children from high-income households have fewer siblings and more educated parents than those born to lower income parents. Teachers report that high-income parents are more interested in the education of their children. Furthermore, children of high-income parents are more likely to go to schools where: parents attend educational meetings at age seven, student-teacher ratios are low at age 11, and a high fraction of students are doing GCEs at age 16 (an optional exam for progressing to further education). As a result, children from richer households develop greater cognitive skills; at age 16, reading scores were 21% of a standard deviation higher on average for children with high-income parents compared to children with low-income parents.

Table 1 describes only a subset of the variables we use. We combine these variables using a factor analytic approach to predict latent time investments, school quality and cognition, similar to Heckman et al. (2013). The factor analytic approach allows us to use all measures available to us by treating them as noisy measures of school quality, parental time, and cognition.

Table 1 Sample means, by parental income

Note: The final column reports P-values from the F-tests testing the null hypothesis of equality of means across parental income tertiles. The time investment measures are teacher-reported measures asked when the children are 7, 11, and 16. Teachers can evaluate parents as very interested, a little interested, not interested at all. We report the fraction of mothers and fathers who are very interested.

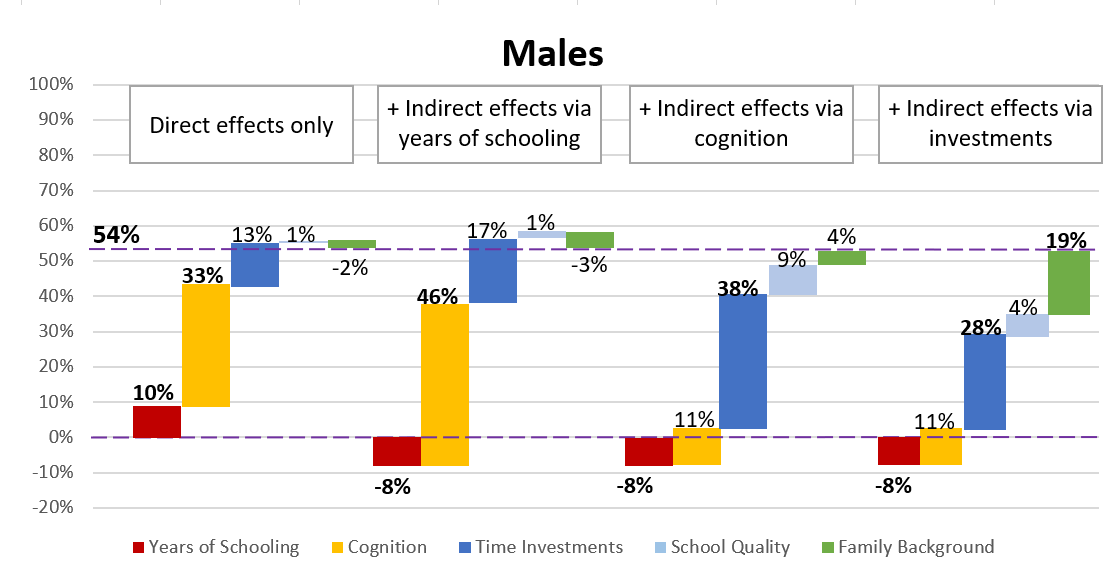

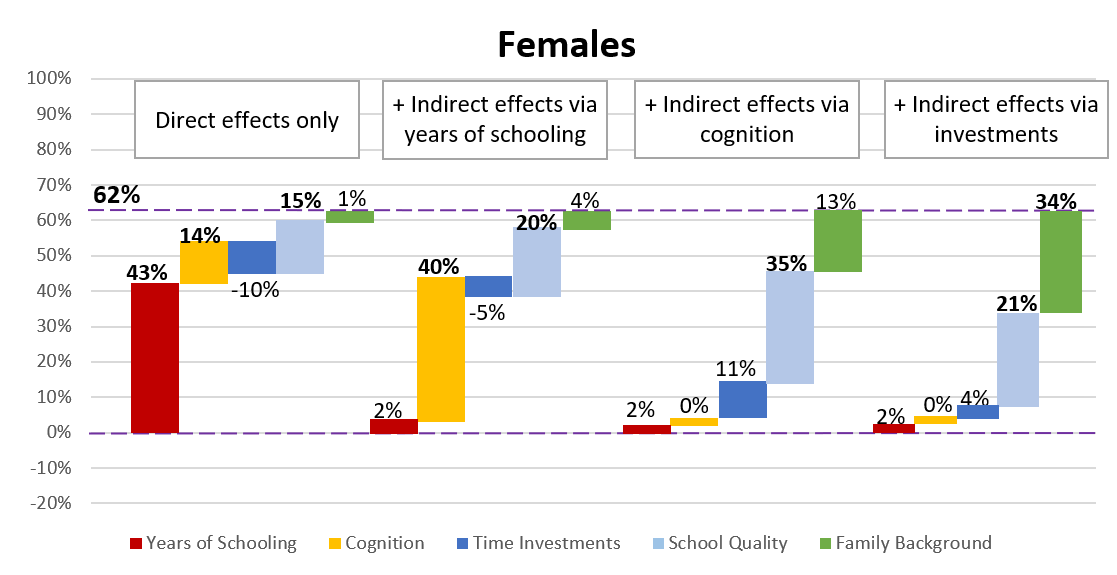

We find the intergenerational elasticity of earnings, or IGE (which is a measure of the relationship between parental and child lifetime income), to be 0.32 for men and 0.24 for women. The first part of Figures 1 and 2 shows the fractions of this relationship explained by differences in family environment, time investments, school quality, cognition at 16, and completed years of schooling when we only allow for direct effects of each variable on lifetime income. These variables explain over half of the IGE –– 54% and 62% for men and women, respectively (the remainder is explained by factors beyond the ones we consider, such as better job networks).

Figures 1 and 2 summarise the main for results for men and women respectively.

Figure 1

Figure 2

In the first panel of each figure, we find that years of schooling and cognition explain significant and large fractions of the IGE, both for men and women. We then investigate whether schooling and cognition are driven by earlier life investments and family background.

In the second panels of Figures 1 and 2, we allow for indirect effects via years of schooling. For example, for cognition, we now additionally account for its effect on lifetime income via its effect on years of schooling. Doing so, we find that the fraction of the IGE that was previously explained by differences in years of schooling can actually be explained by differences in cognition, instead. This suggests that it is not parental income per se, but the higher cognitive levels of children of high-income parents that encourages higher educational attainment.

The next level of our analysis, illustrated in the third panel of each figure, addresses the sources of cognitive skills. We allow for parental time investments, school quality, and family background to affect the IGE not just directly and via years of schooling, but also via cognition. We then find that the fraction of the IGE that comes from the cognition gradient can largely be explained by differences in time and school quality investments received during childhood. This is consistent with previous literature that has found significant effects of parental investments on cognitive development (Attanasio et al. 2016).

Lastly, we let family background – which comprises mother’s and father’s education, and number of siblings – have an indirect effect by affecting investments. Once we do so, family background explains 19% (34%) of the IGE for men (women). This contrasts with the zero effect of family background that we find in our baseline analysis. In other words, family background matters, but only because it affects investments, which then affect cognition and years of schooling. This result is consistent with Carneiro et al. (2007) and Akresh et al. (2019), who find that increases in parental education lead to more favourable child outcomes. However, we also find that even if we control for family background, the remaining parental income gradient of investments explains 28% of the IGE. This suggests that higher parental income directly leads to higher investments in children, and not only runs through family background, a point developed in greater detail in Bolt et al. (2021b). This supports Bastian and Lochner’s (2021) conjecture that the increase in financial resources from programmes such as the Earned Income Tax Credit are what drives improvements in child outcomes.

Thus, we conclude that the main driver of intergenerational earnings persistence are differences in investments received during childhood which subsequently leads to improved cognition and more years spent in education. Many of these investments, such as school quality, are the subject of public policy debate. Our results suggest that policies that equalise these investments could improve income mobility.

See original post for references

This is something I’ve observed in my own wider family, which stretches the spectrum from working class to the professional classes. I don’t see anything geneticly superior about some of the kids I’ve seen grow up, but without question those from the professional and business side of the family have done better, for all sorts of often very subtle reasons. I can’t help but look back at my own family and see those times where my parents – both from poor backgrounds – would have given me nudges in one direction or another had they been more clued into that type of network. It simply didn’t occur to them that success was down to anything but honesty and hard work.

One reason why this sort of analysis is so important is that it shows how shallow a ethnic based view of society can be. In the US, Asians as a broad ethnic class are generally very successful, but not because they are somehow smarter than everyone else. Overwhelmingly, even those who arrived in the US impovrished came from the business and professional classes (especially the Chinese, Vietnamese and Koreans who came in the post WWII period). They understood immediately what was required to get their kids into the upper middle classes of the US and they did it. Its really that simple. You can see this process replicated worldwide. I think sociologists call it the ‘first generation effect’, as its impact can be seen many generations ahead.

I happen to have done a lot of examination of Korean immigrants to the US. What was interesting was how many who came over in the 60’s had been highly educated in Korea, but usually had credentials not recognized in the USA, or faced too steep of a language barrier to get those white collar jobs. Many went into the merchant class because they immediately identified entrepreneurism not as a particularly fun vocation, but it was the fastest way to overcome those dual hurdles.

This book was instrumental in my understanding of how Korean Americans made their way into America: https://www.amazon.com/Blue-Dreams-Korean-Americans-Angeles/dp/0674077059 One of the most fascinating aspects was how Korean class divisions (which were/are stark) carried over to the American context. New Korean immigrants often looked down on Korean immigrants who had come to the states during, say, the early 20th century. Humans have the ability to draw incredibly fine lines, it’s amazing.

The fact is that the social reproduction of class is infinitely complex and you have to be immersed in it to understand it.

This article does a great job breaking down some of the factors, though. That early investment in a kid’s education explained in the article, for instance, just can’t be replaced by anything else.

Yes, there are many examples worldwide, but the more recent influx of east Asians to the US is an excellent example of how across cultures class differences are highly persistent, even if one generation has had its access to wealth and influence cut off. You can see this in immigrants in Europe and many parts of Asia as well. Its very obvious when you see the relative trajectories of South Asian (Indian/Bangladeshi/Pakistani) immigrants to the UK. I’ve read studies that have found this effect lasting centuries and many generations (Albions Seed by David Hackett Fischer is a great book on one aspect of the topic). In Ireland you can still see the pervasiveness of certain old Anglo Norman aristocratic names in the higher levels of business and the professions.

The comedienne Ali Wong has some great observations on this – she has a very funny routine on the differences between ‘fancy Asians’ and ‘jungle Asians’. My Asian American friends have told me that her observations are spot-on.

Fascinating. A friend’s grandfather was a respected attorney in Korea. Fled with his family and ended up working at a convenience store for his entire life in the States. Nevertheless, the children (and grandchildren) were upwardly mobile which was most important to them.

Yes, early, quality education is very important. Parsing that input with the quality of parental support/motivation is likely difficult. In America it is generational wealth that seems to have the strongest correlation to educational/class advancement.

I have friends who are early life educators and they’re convinced the First Five program (Talk-Read-Sing) for children in the first five years of life is essential for brain development and future cognition,

Of course, “success” in American culture has an element of randomness.

“I can’t help but look back at my own family and see those times where my parents – both from poor backgrounds – would have given me nudges in one direction or another had they been more clued into that type of network. ”

Quite. Working class parents cannot provide advice on the appropriate steps to take. They cannot provide a network of advisors or professional guidance. Investment bankers (for example) need to make certain choices. Luck plays a role but there are right and wrong decisions. A bit of appropriate guidance might have gone a long way.

I would imagine the same is true of every field.

Over my 45-year career as a psychologist, I have been fascinated by people who are late bloomers. Because these people are not easily identified, conducting a study is nearly impossible. So, I just interviewed them out of curiosity whenever I encountered them. I often started these conversations by asking: “How old were you when you realized you were smart?” A typical answer was: “When I went to night school after work and started getting A’s.” That usually led to teachers encouraging further study that led to college then graduate studies.

Over the decades, a pattern emerged than can only be described as “tribalism.” The vast majority shared stories of growing up in families and neighborhoods which viewed college (or even good grades in high school) as an act of cultural/familial values rejection. The “We work for a living.” remark was often mentioned as frequently-heard assertion meant to contrast one’s group/family from the managerial classes. Such cultural family values tended to lower expectations for success in post-high-school education which they simply did not challenge while growing up.

As PlutoniumKun mentioned earlier, Asian immigrant over-achievement might be described as motivated by tribalism as well – just emphasizing vs downgrading the value of early diligence, self-sacrifice, and investment in educational excellence.

Quite apart from the obvious reason of wanting their children to better their own station in life, some parents have a more selfish reason for setting their offspring on the trek towards the upper class, I.e. the opportunity to live vicariously through them. This isn’t a factor that would make it into the findings of an official study like the one discussed in the article but you can be sure it comes into the reckoning when parents are deciding e.g. which schools their children attend.

I think this is where the more subtle forms gatekeeping comes in – the upper classes have a particular contempt for those who try too hard to social climb (“they had to buy their own furniture”). Its the difference between those who drive Range Rovers and Land Rovers. A certain amount of aspiration is encouraged, but too much and you become an object of ridicule – in the Old World at least.

One reason that many Celts and Aussie/NZerr have done well in England is that they can bypass the unspoken rules as they don’t get too easily tripped up by accent, or the type of shoes they wear. It is striking when you look at the current Tory party ranks just how many are descended from immigrants who seem to have bypassed the normal route to influence. Likewise, many a Brit has talked themselves into the higher ranks of East Coast American upper classes. They can, in short, social climb without being caught doing it.

what you are referring to is called “habitus” in the social sciences, i believe.

The misguided belief that ethnic differences in intelligence (and thus educational outcomes and incomes) can largely be explained by genetic factors is held by many in our society. It is an attractive belief because it “proves” that the prevailing income distribution is a result of a meritocratic process, where talent is rewarded and the lack thereof punished. It also fits nicely with our tribal instinct to interpret the world through ethnic differences, even though research has continuously shown immaterial differences in intelligence between ethnic groups (works of Richard Nisbet and David Reich). Unlike ethnic differences, it takes mental effort to appreciate that lifestyle choices, culture and other environmental factors are determinative. The challenge we face is to communicate these facts to the citizenry so that informed discussions on education policies can take place.

I thought the class size was interesting.

Isn’t class size being small relatively new? Assume 20-25 year generations, was class size something that was important more than 2 generations ago?

Money buys stuff and time. And as any parent will tell you, what do kids voraciously consume? Your stuff and your time.

presumably/obviously this was beyond the scope of the study—but one has to look at neonatal, childhood nutrition, and lots of other factors for which it’s tough to get good (and inexpensive) data. things like (in no order):

Epigenetic studies bring up a correlation between maternal stress and negative physical/mental health outcomes. easier to have less (acute) stress when there is more money in the bank. And furthermore childhood stress is associated with lower developmental outcomes.

Despite what the Fed/CPI numbers may say….a nutritious diet ain’t cheap for the bottom rungs of the income ladder. If I had to feed a toddler using the US federal child food aid budget, I’d run out of money after spending it all on organic milk and fresh produce.

Time: higher income buys time (or a nanny) to raise a kid. Obviously for the all the parents out there, GOOD childrearing is a huge time sink for everything from educational to physical development.

As an example, I’m a big fan of the Montessori-inspired styles for child raising. However that style is time intensive and if I was an hourly full-time worker, it would be incredibly difficult to have the spare time to offer a kid the freedom to learn and explore unless the kid was sent to a full-time Montessori day care.

Good points Louis. Other factors too would be dental care, and sports, as Yves mentioned. Dental care has a lot to do with self image and how others perceive you. Braces are expensive. If you are poor you cannot participate in organized sports. That limits your physical development, as well as the networking that comes along with it.

I have often heard that with regard to organized sports, but I find it interesting that so many pro athletes, especially in “money” sports (American football, baseball, basketball, soccer in Europe) are from less than privileged backgrounds.

law of large numbers.

to oversimplify, if millions of kids have no outlet but sports, you’ll always find a few dozen every year who are sports stars…with thousands of stories of those ‘who could’ve beem a contender’ but for a twist of fate.

“

…and sports are physical outlets that require both cognitive as well as physical development. While the financial attraction of athletic achievement is real in the disadvantaged community, less than 1% of college level athletes become professional athletes.

It’s the real, live Hunger Games

It was a different time and different political culture, but the local recreation department in my small city required very little in ancillary expenses: shoes for baseball, basketball, and football (until the age of 12-13 the same shoes could be used for each sport) and a glove for baseball. Uniforms, bats, and balls were provided (and track shoes during the brief track season). There were no “travel teams” in any sport. The children of bankers, doctors, and lawyers were teammates with the children of the working class. Our volunteer coaches were from all classes, too. No, the system was not perfect for all the usual reasons, but I had as many friends make it into professional baseball up to AAA and MLB, for example, as now…and another thing, since we had not damaged our throwing arms because we changed sports with the season, we did not need Tommy John or rotator cuff surgery by the age of 17. Not that either really existed back then.

Money buys stuff and time. And as any parent will tell you, what do kids voraciously consume? Your stuff and your time.

Yea, there are the complications.

and there are the Priorities.

There is no human future without children.

Proverbs 22:6

I don’t get that message from the Media and Pundits so frequently that it’s the first thought and the default behavior.

But it is intuitive, and that gives me hope for when our priorities become right ordered.

Jane Gardam’s short story, “Rode By All With Pride,” which takes place in London, presents a bitter view of how the rich raise their children. Subtle and breathtaking, which Gardam can do so well.

Here is a discussion (so spoilers) of the story:

https://mookseandgripes.com/reviews/2016/03/30/jane-gardam-rode-by-all-with-pride/

Seeing the data in Table 1 I’m a bit suspicious about the conclusions they draw. They identify parental investment as the ‘transmission belt’ which translates income into higher cognition and more years of schooling. But as you can see in the table, the investment (the way they measure it) is not that different for different income tertiles. For 16 years the difference is not significant (p-value 0.19).

Also, I wonder why they chose ages of 7 and 11 to measure parental investment. There might be a good reason for this, but it also could be that at other ages the gap was less impressive.

no idea why they chose those ages, but multiple higher reasoning processes come “online” during those years.

the kinds of reasoning processes that heavily impact cognition, thus ability to engage in higher, more abstract levels of schooling.

just a thought.

The years 7-11 and probably earlier might well be critical to the development of one’s cognitive potential. IQ test scores are relatively fluid before ~10 years of age, but gradually stabilizes until arriving at the adult level after ~15. Parental intervention in the early years therefore has the greatest effect on the child’s adult IQ score, which correlates with her SAT score, lifetime educational attainment and income.

IQ is not a measure of cognitive potential or anything of the sort.

I can believe that it correlates with income and educational attainment.

‘We exploit unique data from the National Child Development Study (NCDS), which initially surveyed families of the entire population of children born in one particular week in 1958 and has followed them up until today.’

I wonder if they are doing this on a periodical basis. Can you imagine what would turn up if they did this every five or ten years apart and compared the differences? I mean that 1958 cohort would have turned 18 in 1976 and America was a very, very different country back then for a person leaving high school, even for one that was from a wealthy family. Imagine the differences. One that pops into my head is how kids from wealth families can work for corporations nowadays for several months as interns and get a solid leg up whereas most kids cannot work for free for corporation for that long.

Stealing a pun-punch line from a comic I saw, though this punch line was used in a different context —

Why do rich parents have rich children?

It must be something in the father’s jeans.

Academics gotta’ academic. I haven’t heard about the dreaded “death tax” for a couple of decades now. This was a major concern of our influential class of bloviators for quite some time and has apparently been settled to their satisfaction. By all means put me in the good company of Adolph Reed and apply the “class reductions” smear, but all indications are that we are swiftly moving from the transitional phase of oligarchy to aristocracy. Of course one could argue that we have always had an aristocracy…argue away.

From Investopedia:

Most states have neither an estate tax, which is levied on the actual estate nor an inheritance tax. These taxes fall mainly on distant relatives or those completely unrelated to the deceased. Spouses are always exempted, and immediate family members—children, parents—often are as well. A dozen states impose their own estate taxes, and six have inheritance taxes, both of which kick in at lower threshold amounts than the federal estate tax which is $11,700,000.

Oh, the “death tax” nonsense is still alive and kicking: https://www.nrsc.org/press-releases/new-ad-the-pelosi-greenfield-death-tax-on-iowa-families-2020-07-14/

I’m sorry but I just can’t get on board with this kind of analysis. The entire structure of our economy ensures (more and more with each passing day) that the bulk of people will be condemned to barely scraping by, an ever-shrinking percentage will have a comfortable but not extravagant income, and a few will have a ridiculously over-sized share of wealth and income. This kind of analysis implies that this structure can be meaningfully altered by some interventions during childhood, but that is just not the case. There are only so many well-paid jobs available, only so many executive vice-presidencies to go around. Even if we were to equalize the quality and length of schooling for every child in the country, most of them would still have to work low-paid jobs because that’s what our economy has on offer.

And as much of this claims to be an analysis of why the children of the rich tend to be rich themselves, it’s just as much an explanation of why the children of the poor tend to wind up poor. And the answer, apparently, is that the children of the rich are just smarter, er…have higher cognitive skills. This whole paper comes off as an apologetic for income inequality and decreasing social mobility. Inequality isn’t a natural outcome of an economic system designed to create and perpetuate it; no, it’s because poor parents don’t care about their kid’s education as much as rich parents do!

As with much economic analysis, I object not so much to the methods or findings presented, as to the unspoken assumptions about the nature of our economy and society that the analysis relies on.

This is the closest post so far to how I looked at this article. It clearly presumes, and explicitly so, that the goal is to increase income mobility.

I’d prefer to increase income stability. It’s nice to know there is a route upwards, but it’s more conducive to citizenship, civic participation, and probably overall well being (someone get me a study!) to know that your chance of downward mobility is low.

I’d rather have us work towards a low cost economy than an economy of “equal opportunity.” An opportunity at what, as you point out. It could just be a chance as good as a lottery ticket. No thanks. I’ll just take my daily bread and spend my time as I choose.

The thing is, you can’t have capitalism without also having an exploitable poor underclass. There is no such thing as capitalism without poor people.

The unspoken assumption behind articles like this one from neoliberal cheerleaders Vox is that poverty can be eliminated by tweaking capitalism in the “right” ways. It doesn’t work that way. Even the socialist [sic] capitalism of Scandinavia never managed to do that.

Funding social programs and the like can reduce the severity of poverty under capitalism but it can’t change the fundamental winners and losers nature of the system.

What the west really needs is a new way of doing things. It could learn a lot from China here. Not by copying the Chinese system but by trying different things and seeing what works best. Of course the west will never do this because a) it still believes liberal capitalism is the pinnacle of human achievement and b) it has weakened the state and, in the economic realm, made it subservient to private capital.

As long as the west is blinded by neoliberal ideology the only “change” on offer will be the Obama variety PR exercise version or the technocratic edge tweaking proposals coming from outfits like VoxEU.

Historically another type of “change on offer” can come from an educated class on downward trajectory: violent revolution. No one like to talk about that in Amrika. The Chinese certainly understand this dynamic.

At the risk of partially de-anonymizing myself, I’ll come out and say I spent grades 7-12 at The Haverford School in the 90s. My dad grew up dirt f***ing poor, managed to come up through two ivies and is now a well-regarded invasive cardiologist. Paid cash for private school and college for me and my sister, both private. BS for me, BS and MS for her. I was born lucky and realize the space to f*** up sometimes and have a support network to fall back on is a luxury most people don’t have. I’m keenly aware of my advantages and never, ever buy the lie that the world’s ills are a failure to “pull yourself up by your bootstraps”. I won the “sperm lottery”, as the vulgar expression goes.

The article’s claims suffer the major flaw I see in most economic analyses: treating humanity as a set of abstractions in some model, variables to be tweaked in a closed system to produce a theoretically perfect outcome that pays off a guilty conscience. But capitalism is structured as a predatory model, which requires violent dislocations in the wealthy enclaves to remedy, a reality those classes violently oppose. I’ve given up on the notion of democratic socialism ever taking root here.

Private school has afforded me the network effect. Success is predicated on networking more than anything else. I can hit up my alumni network for access other people don’t have. I wore a tie and jacket daily and in doing so learned to garb myself in signifiers of a certain class. I learned how to be WASPy, comfortable moving in circles of the wealthy without feeling like an impostor. I can navigate the world of wealth and privilege comfortably because private school taught me how. I adopted the affect that legitimizes me in those circles.

I’m not a braggart, not smug, and my upbringing certainly doesn’t increase my value over anyone else, be they broke or astoundingly rich. It’s just me sharing my experience. And by virtue of being upper-middle class, I’m also comfortable navigating the blue collar world without coming off like a privileged a**hole.

As Fitzgerald wrote:

“Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me. They possess and enjoy early, and it does something to them, makes them soft where we are hard, and cynical where we are trustful, in a way that, unless you were born rich, it is very difficult to understand. They think, deep in their hearts, that they are better than we are because we had to discover the compensations and refuges of life for ourselves. Even when they enter deep into our world or sink below us, they still think that they are better than we are. They are different.”

“And by virtue of being upper-middle class, I’m also comfortable navigating the blue collar world without coming off like a privileged a**hole.”

Many of our class believe this to be true, but I see them as self-deluding. I liked the rest of your comment.

The main purpose of going to a “good school” is meeting the “right people” so you can get into the “right clubs,” have “good clients,” and make “great deals.” Learning to play golf helps. But not actually necessary to do well in school.

Let’s think what a meritocracy would look like.

Let’s work it out from first principles.

1) In a meritocracy everyone succeeds on their own merit.

This is obvious, but to succeed on your own merit, we need to do away the traditional mechanisms that socially stratify society due to wealth flowing down the generations. Anything that comes from your parents has nothing to do with your own effort.

2) There is no un-earned wealth or power, e.g. inheritance, trust funds, hereditary titles

In a meritocracy we need equal opportunity for all. We can’t have the current two tier education system with its fast track of private education for people with wealthy parents.

3) There is a uniform schools system for everyone with no private education.

Now we can see how they tilt the playing field.

Because I am a bad parent, my daughters get taught mathematics by me. I keep hoping to start them on classics (no Latin or Greek cos I have very little of them, just the Histories and the literature) but so far they have resisted. Despite this resistence, they still get a certain amount of history, geography, and languages to go along with the soccer and piano.

This happens because their parents are graduates (and THFC fans). When they are older, they will be sent overseas to spend time when various “uncles” and “aunts” in the UK, Italy and France. Lawyers, Company Directors, AI consultants etc.

How exactly do you plan to level the playing field? My job is to make sure it is as unlevel as possible.

All of this is without any private school. I dont believe in them.

The usual arguments towards making no effort whatsoever.

Do you think your children would struggle on a level playing field?

good of you to acquaint them with the concept of a lifetime on stultifying disappointment ;)

“Gumption is a great hill climber” from a man who mistakenly rode the Lusitania in an effort to stop WW1, (Elbert Hubbard, the Roycrofter).

Gumption comes from parenting. It was the common trait for my classmates selected for Annapolis in the 60s. Maybe one in six grew up in upper-middle-class families but it seemed rather rare. None of the twenty in my company enjoyed money from home yet today almost all have led highly successful business and, or military careers. Where does gumption come from? Or perhaps more importantly where does it die? Have interviewed and employed more than a thousand different souls over the years only lack of gumption prevents personal success. And yes some mediocre engineers found their future as managers.

I went to a college established by well-meaning utopians in the mid-19th century for poor children from a disadvantaged region of the country. The founders felt education would enable the impoverished young of the area to raise themselves and their neighbors up. It was and still is tuition free. The instruction afforded us including additional enrichment opportunities (fine arts performances, semesters abroad, internships etc.) was the equal of anything available to the Ivy League, yet an informal survey of alumni turns up few examples of our quality education generating wealth. Most of us are barely middle class. Some are as poor as when they started out if not poorer. Which begs the question- Can you educate people out of poverty?

Many of us started with health disadvantages (poor teeth, obesity, asthma.) Heck, I went to college with people who were experiencing their first indoor plumbing. Upon graduating most didn’t have cars or money to move to coastal cities or start businesses. Some of us were parents at a young age. Most importantly we did not have influential or well-connected family or friends who could steer us effortlessly toward more profitable opportunities. By way of example, It was decades after graduation when I was made aware that the university twenty miles away attended by the children of the local gentry, had its own country club where Muffy and Biff could network with their fellow alumni and their parents. We couldn’t even conceive that such a thing existed.

My fellow alumni are smart people and hard workers, but poverty is a complicated issue. And people who won the birth lottery have a nasty tendency to credit their own merit or “gumption” for their success.( Or as the late, great Molly Ivins said of George W. Bush- “Poor Georgie, Born on third base, thinks he hit a triple.) Systemic problems require systemic solutions and too many people at the top think the current set-up is working just fine.