By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

“…sap and impurify all of our precious bodily fluids…” — Jack D. Ribber, Doctor Strangelove

Jack D. Ripper was directionally correct, wasn’t he? And if we cross out “flouridation” and write in “PFAS,” and cross out “commies” and write in “industrial capitalists” he was pretty much on the nose, wasn’t he (“certainly without any choice”).

PFAS (“Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances”), popularly called a “forever chemical,” may sound like a dry topic, but if you drink water (or eat food grown in American soil), you should be aware of it, and concerned. You may be not be interested in PFAS, but PFAS is interested in you.

This is a survey post on PFAS. First, I’ll look at the whistleblower who first raised awareness of PFAS. Then, I’ll look at PFAS chemistry (why it is “forever”), products that use PFAS (lots), PFAS harms, how people are exposed to PFAS (water, soil, air), PFAS remediation (it is possible), and PFAS regulation. Having set the stage, I will then look at Maine’s pioneering PFAS legislation (good, with some problems), and conclude.

The PFAS Whistleblower

From NC in 2019:

About a third of the way into the film Dark Waters, Rob Bilott, played by Mark Ruffalo, is lying in bed with his eyes open, looking anxious. The lawyer has spent the past year poring over thousands of internal documents from the DuPont chemical company, and has pieced together a harrowing story. The company has been dumping a chemical called “C8” into the air and water outside of its plant in Parkersburg, West Virginia, for decades, and withholding information about the dangers it posed to human health.

Bilott gets out of bed, boots up a boxy PC from the early 2000s, and opens a blank document. He hesitates for a moment — he’s about to do something unprecedented in his corporate law firm — then begins typing a letter to the Environmental Protection Agency outlining everything he’s gathered about DuPont’s cover-up.

That letter became known as “Rob’s Famous Letter” among Bilott’s colleagues, as Nathaniel Rich reported in the New York Times Magazine article that inspired the film. If Bilott had never sent it, the world might still be blind to the dangers of C8 and other per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances known collectively as PFAS — a class of nearly 5,000 substances called “forever chemicals” because of how long they persist. The nickname is hardly an exaggeration. Some of them, like C8, literally never break down in the environment.

Bilott (who did not graduate from an Ivy League law school) is still litigating environmental cases, which is good. We need more like him, many more. See the APPENDIX for the splendid rant that introduces a movie with a similar theme: Michael Clayton.

PFAS Chemistry

What then are PFAS? (Since the “S” in PFAS stands for “substances,” we don’t have to say PFAS’s. That would be bad. On the other hand, “PFAS are,” not “PFAS is.) From WBUR:

There are around 4,700 chemicals in the PFAS family, and they all have two things in common:

- They’re all man-made.

- They contain linked chains of carbon and fluorine.

The bond between carbon and fluorine atoms is one of the strongest in nature. That means that PFAS chemicals don’t degrade easily; they stick around in the human body and the environment for a long time, and are very stable in water. That’s why some people call them “forever chemicals.”

We hear a lot about PFOS and PFOA, but those are only two of the 4,700 PFAS chemicals. From the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency:

PFOS and PFOA are the most recognized and most studied individual compounds in the larger group of PFAS chemicals. Major manufacturers of PFAS in the United States agreed to phase out the use of PFOS, PFOA and other select PFAS in 2006, but manufacturers that are not part of this agreement may still be producing them. PFOS and PFOA are still manufactured and used in products made overseas that may be shipped for sale in the United States.

PFOS – Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) was the key ingredient in the stain repellant Scotchgard, and was used in surface coatings for common household items such as carpets, furniture, and waterproof clothing.

PFOA – Perfluorooctanoic acid was used in the production of nonstick coatings for cookware. The best known of these coatings, PTFE or Teflon™, is made from PFOA and may contain some traces of PFOA. It was also used in production of carpets, upholstery, clothing, floor wax, and sealants.

Nobody really needs Teflon or Scotchgard, so I originally thought PFAS would be easy to deal with, because we would be able to stop manufacturing excessively stupid products. Sadly, no.

PFAS Products

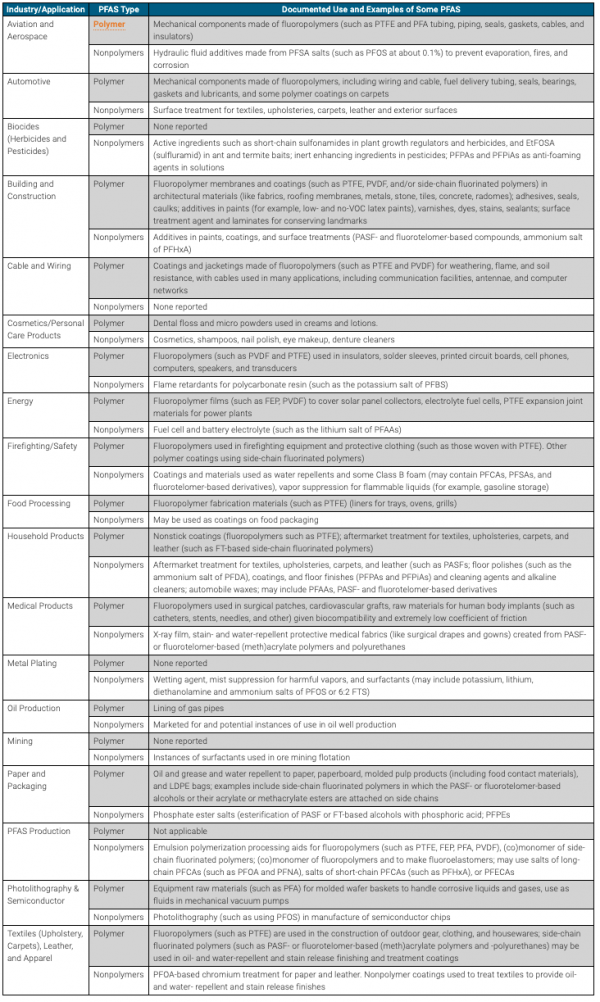

PFAS are used because of their unique oil- and water repellent (ScotchGuard-like) properties. Here is a handy table of PFAS uses from the Interstate Technology and Regulatory Council. From the Introduction to the table:

Table 2-4 provides a general (not exhaustive) introduction to some of the uses of PFAS fluorochemistries that are, or have been, marketed or used (3M Company 1999)) (Poulsen 2005) (OECD 2006) (Washington State Department of Ecology 2012) (OECD 2011) (OECD 2013) (Fujii, Harada, and Koizumi 2013) (OECD 2015) (FluoroCouncil 2018) (Henry et al. 2018). The specific applications for all PFAS are not well documented in the public realm. For example, of the 2,000 PFAS identified in a 2015 study, only about half had an associated listed use (KEMI 2015).

So the massive table that immediately follows is a “general (not exhaustive) introduction to some of the uses of PFAS:

So when you read material like this…

[PFAS] are used in many consumer and industrial products, including firefighting foam, nonstick coating and food packaging.

… think of the table above. The range of uses is much more broad (and hence the chemical is that much more pervasive).

PFAS Harms

From Grist:

Since the 1940s, [PFAS] have been leaching into the soil, the groundwater, and our bodies. PFAS pollution is now so widespread that the chemicals are estimated to be present in 99 percent of Americans’ bloodstreams. Researchers have even found them in the bodies of polar bears.

…[S]cientists say they’ve leached into the environment and built up to potentially hazardous concentrations in drinking water. Chronic exposure to low levels of PFAS has been linked to cancer, developmental health issues, higher body weight, and more. The EPA’s current safety recommendation sits at 70 parts per trillion, but some evidence suggests that guideline should be 700 times lower.

Also, since PFAS hang around forever, they keep causing harm. You ingest PFAS, excrete PFAS, and in the fullness of time some other living being ingests the same, unchanged PFAS. This is unlike even other exceptionally nasty man-made toxic substances like PCBs, which do break down, or even dioxins, which break down over a decade or so. So harm just keeps building.

PFAS Exposure

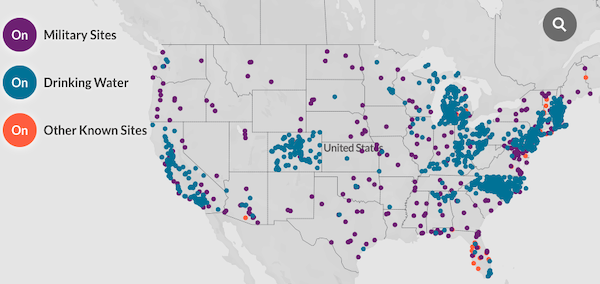

Here is a map of PFAS exposure sites from the Environmental Working Group:

At least for Maine, this is only an approximation; Maine appears to have only five sites, four of them involving military aircraft. (Airport fire-fighting foam is a source of PFAS). Maine should be so lucky!

From Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, here is a summary of how humans are exposed to PFAS:

Human exposure to PFAS occurs through several pathways, including ingestion of contaminated drinking water, food and household dust, inhalation of indoor air, and contact with other contaminated media. Drinking water sources include rivers, lakes and groundwater may also be contaminated with PFAS originating from industrial sources. There may also be significant exposure risk from PFAS-contaminated sewage sludge and recycled water from wastewater treatment plants, which are often used in agriculture, with exposure through contaminated soils and crop foods.

Here is a more detailed breakdown of the major sources:

Aqueous Film Forming Foams (AFFFs). Fire training facilities undergo extensive and prolonged use of AFFFs, which has caused large volumes of PFAS to be released into adjacent soils during short periods. From there PFAS leaches into groundwater supplies.

Landfill Leachate. In a landfill, soil chemistry is heavily compromised which impacts natural degradation processes due to the number and nature of pollutants present. PFAS within waste can become mobile and leach into pore water creating contaminated leachate. Fortunately, modern sanitary landfills typically have stringent mechanisms for preventing and mitigating leachate from entering groundwater. However, the controlled discharge of leachate to wastewater treatment plants is allowed. Reinforcement of smaller and older sites to stop the threat of local point source contamination into surrounding soil and groundwater is paramount. PFAS will continue to persist in the landfill and continue to increase over time.

Biosolids and Recycled Water. Point sources of PFAS transmission to agriculture occurs through the application of recycled water from wastewater treatment plants, landfill leachates and biosolids applied to agricultural land… Once in agricultural lands, PFAS can be taken into the root systems of plants including cereals, fruits, and vegetables.

PFAS in Soil Systems. As a consequence of these major sources of PFAS, these compounds are almost ubiquitously detected in the environment. Research has indicated that soil organic carbon content is the dominant solid-phase parameter which affects the adsorption of PFAS.

Landfills, biosolids, and soil systems will become important when we get to Maine.

PFAS Remediation

By location:

Wastewater Treatment plants. From Chemical and Engineering News:

[T]he best on the market still leaves room for improvement. Reverse osmosis, ion-exchange resins, and granular activated carbon, though capable of trapping PFAS, were not designed to specifically bind these newly scrutinized and little-understood pollutants. These technologies can also allow smaller PFAS molecules to slip through and are vulnerable to fouling from other substances in the water, causing them to lose efficiency. Plus, they create a concentrated waste stream.

So now, researchers are not only designing adsorbents that specifically take up PFAS but are also developing treatment methods to completely destroy the molecules rather than merely sequestering them. And they’re doing this with an eye toward making as little long-term waste as possible.

Wastewater Treatment plants. From Grist:

In a paper published last month in the journal Environmental Science & Technology Letters, [Michael Wong, a chemical engineer at Rice University] and his team of researchers found that boron nitride — also known as BN and commonly used in cosmetics and electronics — could destroy up to 99 percent of a type of PFAS called PFOA in about four hours.

The research centered around a process called photocatalysis — a chemical reaction in which tiny, semiconductive particles are suspended in contaminated water and “excited” by ultraviolet light. With the right kind of particles, that reaction can be strong enough to degrade the durable carbon-fluorine bonds of PFAS.

In the soil. From Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology:

Biodegradation has the potential to form the basis of a cost-effective, large scale in situ remediation strategy for PFAS removal from soils. Both fungal and bacterial strains have been isolated that are capable of degrading PFAS; however, to date, information regarding the mechanisms of degradation of PFAS is limited.

Here is one example. From Chemical and Engineering News, phytoremediation:

A new study reports that over a 100-day period in the lab, a wetland bacterium removed the fluorine atoms from up to 60% of perfluorooctanoic acid… Although the defluorination is slow, this Feammox research is potentially transformative,” showing for the first time that these fluorinated compounds can be biodegraded, says William Cooper, an environmental chemist at the University of California, Irvine. Compared with pumping groundwater and applying chemical or physical treatments, biological remediation can be done in place relatively easily and more cheaply, he says.

A second example. From Frontiers, mycoremediation:

To date, research is limited on their ability of fungi to degrade PFAS. This is perhaps surprising given they are known to degrade lignin, one of the most recalcitrant natural compounds along with many toxic natural and xenobiotic compounds including organochlorines [e.g., DDT and DDE, organophosphates, pesticides, including chlorpyrifos and polychlorinated biphenyls (Beaudette et al., 2000) andpolyaromatic hydrocarbons (Moghimi et al., 2017)].

No research because there’s not enough money to be made selling fancy equipment with a maintenance contract? (Where’s Paul Stamets when we need him?)

PFAS Regulation

PFAS regulation is, as one might expect, practically designed to encourage externalities. From NPR:

“These are a very broad class of chemicals — probably 5,000 or more — and it seems like new ones are being produced all the time,” [ Linda Birnbaum, director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Toxicology Program] says.

In most cases, U.S. chemical regulations do not require that companies prove a chemical is safe before they start selling it. It’s up to the EPA to determine whether a substance is unacceptably dangerous and under what circumstances, and typically such analyses begin only after public health concerns are raised.

As a result, “we really don’t know much about the great majority of these chemicals,” says Birnbaum.

One approach that scientists supported by the National Institutes of Health are taking is to analyze hundreds of PFAS varieties at once. The goal is to identify subgroups of PFAS with similar characteristics, so scientists won’t have to do a battery of toxicity tests on each individual chemical.

“There’s no way that we’ll ever be able to test 5,000 or more PFAS,” Birnbaum explains.

Oh.

Maine’s PFAS Legislation

Finally we come to Maine. Here is the headline: “Maine outlaws PFAS in products with pioneering law.” Not quite, as we shall see. But not bad! Interestingly, alert reader oaf let us know the score back in 2019, commenting on a post on the lead in Flint’s water:

There’s another widespread toxicity issue, yet to be addressed to my satisfaction: PFAS/PFOS in composted sewage sludge provided to commercial and residential users…it has shut down at least one farm here (in Maine), and the state authorities have decided that it is still fine to keep providing it!…How much locally produced food is grown with this chemical in it? Food providers should have to disclose if their products have been grown with this stuff; so consumers can have a choice whether to be part of this long-term experiment. once it is in you; it is allegedly in you forever…It seems a convenience to municipalities to sell it….but at what cost to society?

Maine Public Radio summarized the legislative state of play in early July. “LD” stands for “Legislative Document,” i.e., a bill:

One of the most consequential new bills, LD 129, lowers the level of PFAS contamination that the state considers safe for drinking water to 20 parts per trillion — one of the nation’s lowest limits and down from a federal advisory level of 70 parts per trillion that the state had previously used.

Other bills that have received [Governor Janet] Mills’ signature will ban the aerial application of PFAS chemicals; extend the statute of limitations for lawsuits involving PFAS pollution to six years after the pollution is discovered, rather than six years after it first occurred; and direct Maine’s agriculture department to research crops that can be safely be grown on contaminated farms.

Some of the other biggest bills are still waiting for the governor’s signature. One of them, LD 1600, would require the state to systematically test for PFAS pollution in all sites where municipal and industrial wastewater sludge has historically been applied, so that those areas can be remediated.

Another unsigned bill would restrict how often firefighting foam that contains PFAS can be used in Maine.

A third measure, LD 1503, would go even further to reduce the use of PFAS in Maine, by first requiring manufacturers to report when they are used, and then phasing them out entirely by 2030, except in cases where companies can demonstrate there are no alternatives.

Let’s look at LD 129, LD 1503, and LD 1600 in turn. LD 129 and 1503 were both passed on an emergency basis, meaning by a two-thirds vote, and signed by Governor Mills. LD 1600 has passed, but as of July 15 had not been signed.

LD 129 was passed and signed on June 21, 2021. This is a municipal water systems testing statute. From the text:

On or before December 31, 2022, all community water systems and nontransient, noncommunity water systems shall conduct monitoring for the level of PFAS detectable using standard laboratory methods established by the United States Environmental Protection Agency in effect at the time of sampling. Monitoring under this subsection must be conducted for all regulated PFAS contaminants and additional PFAS included in the list of analytes in the standard laboratory methods established by the United States Environmental Protection Agency in effect at the time of sampling.

And:

If monitoring results under subsection 1 or 2 confirm the presence of any regulated PFAS contaminants individually or in combination in excess of 20 nanograms per liter, the department shall:

A. Direct the community water system or nontransient, noncommunity water system to implement treatment or other remedies to reduce the combined levels of regulated PFAS contaminants in the drinking water of the water system below 20 nanograms per liter; and

B. Direct the community water system or nontransient, noncommunity water system to issue a notice to all users of the water system to inform them of the detected PFAS concentration and potential risk to public health until the treatment under paragraph A is completed.

Which is all good, I suppose, depending on how many of the 4,700 PFAS compounds the EPA’s standard laboratory methods detect, and what level of funding is required for “treatment or other remedies” (bottled water?).

LD 1503 became law on July 15, 2021. This is the “phase-out” statute. From the text:

C. The department may by rule identify products by category or use that may not be sold, offered for sale or distributed for sale in this State if they contain intentionally added PFAS. The department shall prioritize the prohibition of the sale of product categories that, in the department’s judgment, are most likely to cause contamination of the State’s land or water resources if they contain intentionally added PFAS. Products in which the use of PFAS is a currently unavoidable use as determined by the department may be exempted by the department by rule. The department may not prohibit the sale or resale of used products.

D. Effective January 1, 2030, a person may not sell, offer for sale or distribute for sale in this State any product that contains intentionally added PFAS, unless the department has determined by rule that the use of PFAS in the product is a currently unavoidable use. The department may specify specific products or product categories in which it has determined the use of PFAS is a currently unavoidable use. This prohibition does not apply to the sale or resale of used products.

So, the state can prohibit product categories, and individual products. That makes sense. But “currently unavoidable use” looks like a pretty big loophole to me. From the text:

B. “Currently unavoidable use” means a use of PFAS that the department has determined by rule under this section to be essential for health, safety or the functioning of society and for which alternatives are not reasonably available.

Well… “reasonable,” IIRC means up to a judge or jury. So, given that the vpters of Maine were exercised enough for these bills to pass as emergency legislation, I’d say that’s not a problem. But “essential for… functioning of society”? ScotchGuard, probably not. A paper mill? Maybe so.

LD 1600 was passed by the legislature on Jul 15, 2021. This is the landfill sludge leachate bill. From the text:

On sludge:

Sec. 2. Testing of locations with land applications of sludge or septage for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substance contamination. The Department of Environmental Protection shall develop and implement a program to evaluate soil and groundwater for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances and other identified contaminants at locations licensed or permitted prior to 2019 to apply sludge or septage.

1. The department may exclude a location from evaluation under the program for good reason, including, but not limited to, upon a determination that no sludge or septage was actually applied at the location or that the location is no longer owned or controlled by the licensee or permittee and the department is unable to obtain authorization to evaluate soil and groundwater at the location. As part of the report required under the Maine Revised Statutes, Title 38, section 1310-B-1, subsection 2, paragraph C, the department shall identify any location thus excluded and describe the reason for the exclusion.

Surely we ought to be able to test the soil no matter the ownership status of the property? And what’s this “for good reason” bushwa?

On leachate:

Sec. 3. Testing of landfill leachate for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substance contamination. The Department of Environmental Protection shall develop and implement a program for the testing of leachate collected and managed by solid waste landfills for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substance contamination.

1. Notwithstanding any provision of law to the contrary, within 90 days of the effective date of this Act, the department shall require each licensed solid waste landfill to conduct periodic testing of leachate collected and managed by the landfill for all perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances that may reasonably be quantified by a laboratory certified under the Maine Revised Statutes, Title 22, section 567. A solid waste landfill that conducts testing of leachate pursuant to this section shall provide the department with the results of that testing.

2. On or before January 15, 2024, the department shall submit a report to the joint standing committee of the Legislature having jurisdiction over environment and natural resources matters regarding the testing program implemented under this section, including a description of the results of such testing and any recommendations, including proposed legislation. After reviewing the report, the joint standing committee may report out legislation related to the report.

For whatever reason, the other statutes say “PFAS.” This one says “perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substance.” I don’t know if this is meaningful or not, but the landfill lawyers (who write the landfill statutes) are as twisty as corkscrews. More centrally, the landfills do the testing, not a third party. Are you kidding me? Come on, man.

So, all in all, a good year’s work at the Maine State Legislature (and amazingly enough, on a bipartisan basis). As so often these days, however, it’s not clear that good will be good enough. For example, just as alert reader oaf wrote in his comment, Maine paper mills — which have even more clout than landfill operators — create sludge, which has either been treated by them and spread on fields, or has been processed by wastewater treatment plants and then spread on fields. From the Portland Press Herald:

Paper mills have used a lot of PFAS – and in some cases still do – in the coatings that keep grease or liquids from soaking through picnic plates, takeout food containers, pizza boxes, microwave popcorn bags and fast-food wrappers.

Determining which Maine paper mills have used PFAS in their manufacturing processes is extremely difficult because they were not required to report that data under either state or federal laws. Paper companies are also notoriously competitive and secretive about their processes.

According to records compiled by the Maine Department of Environmental Protection, which licensed and regulated the land application of sludge, eight paper companies spread more than 500,000 cubic yards of paper mill waste in Maine between 1989 and 2016. That is a conservative and potentially incomplete figure, nor does it include the hundreds of thousands of cubic yards spread by wastewater treatment plants, some of which process paper mill sludge and wastewater.

Great Northern Paper, which operated mills in the Millinocket region, applied more than 100,000 cubic yards of waste in the 1980s and 1990s in towns or unorganized territories in Penobscot and Aroostook counties, according to an analysis of the DEP data.

The application sites were fully licensed and approved by the DEP under a state-promoted “beneficial reuse” program that provided farmers with free nutrients for their crops and helped municipalities and sewer districts avoid paying landfill costs – costs ultimately borne by ratepayers.

DEP, good job.

Conclusion

Maine’s poster boy for PFAS contamination is Nathan Saunders, whose well and land were contaminated by toxic sludge. They’d been drinking the water for decades, and Saunders has the PFAS bloodwork of a 3M factory worker. Here’s a photo of his farm:

Everything about that photo says rural Maine, from the surprisingly big sky, to the set and roof of the house, to the slope of the hill, and to summer’s intense green, so green as to be tropical. It really frosts me that every bit of that scene — from the well in the foreground, to the net of green plants, to the soil itself, could be toxic. Perhaps ecoside is not to strong a word.

APPENDIX

The opening scene of Michael Clayton:

Like a glaze, a coating…

I don’t know enough about the technology to know if it is feasible at the requisite level of sensitivity, but I’m pretty confident that there are forms of spectroscopy (for example, Raman spectroscopy) that can detect specific bond types and yield quantitative estimates of the number of atoms with those bonds present in the sample. If C-F bonds can be unambiguously distinguished from C-X (X not F) bonds, it might not be necessary to seek to identify specific PFAS species in a sample; it might be enough to know “how many C-F bonds are in the sample?” to get a reasonably accurate sense of the concentration of all PFAS present.

20 parts per trillion sounds like a really low concentration, but …

Taking C8 as a representative PFA substance, with density 1.8 g/cm^3, the 20 nanograms/liter would be the equivalent of a particle of C8 with a volume of roughly 0.011 mm^3 in each liter.

If one’s drinking water were contaminated at that level, drinking 1/2 gallon of water per day would imply the ingestion of about 8 cubic millimeters of PFAS per year.

No — I’m off (high) by a factor of 1000 in the volume calculation. Make that .008 cubic mm per year, a small speck.

I don’t see why the dilution factor matters if there are documented medical effects. (Also, the mulch I got from the landfill operator was one of the ickiest substances I ever touched, and it killed off a whole bed.)

My thought was that “the amount ingested at that concentration is a macroscopic quantity over time” — an alarming thought given the toxicity of the substances. The corrected calculation is the volume of a cube 1/5 of a millimeter on a side. That sounds like a lot to me.

—

I’ve seen really nasty “garden soil” sold in some home improvement centers. I wonder if that has a similar source. Best to make one’s own compost, I suspect.

If possible the mulch ought to be tested for the Bayer/Monsanto product. It is distressingly common for animal manure to be contaminated with those products.

There are rumors of whole bed die back here in NC.

A key point that always has to be emphasised over and over when addressing ‘forever’ chemicals – and I include scientists in this – is that ‘the dose equals the poison’ can be highly deceptive. When dealing with endocrine disrupting chemicals – and this includes PFAS – small quantities can actually be more toxic than high levels. The body can recognise its being ‘assaulted’ with high levels and block the receptors, while smaller levels can fool our defense systems into accepting the intruder. I don’t know if there is research into this with PFAS, but its been demonstrated many times with other such persistent endocrine disruptors, such as dioxins.

I stress this because I have heard many, many times statements from people who should know better when they talk about ‘threshold’ or ‘safe’ levels. When you delve into the background of where these ‘safe’ levels come from, very often they are simply the level that can be detected at the time the regulations were drawn up, they are not based on sound science.

Put another way – there is no scientifically sound basis for allowing any – not even the smallest level – of these chemicals into the environment. We have absolutely no idea what they do over the long term, especially when they are bioaccumulating and interracting with a myriad other such chemicals we’ve dumped into our ecosystems and bodies.

As for leaching from landfill – unfortunately it is excrutiatingly difficult to truly monitor what is leaching from landfills, which is why so many regulatory bodies simply choose a few representative chemicals and attempt to monitor and map them. This is based on an unspoken assumption that most contaminants follow the same pathways. This is a very dangerous assumption, not least because those chemicals that are hygrophobic will have very different pathways from the soluble compounds that are usually used as markers.

I was involved in anti-landfill and anti-incineration campaigns back in the 1990’s, and at the time I was an enthusiast for treatment systems that focused on composting. But for the reasons Lambert outlines, I’m a lot less sanguine about them now. Incineration can at least break down substances like PFAS, but at the expense of creating other problems such as dioxins. Plus incineration doesn’t solve the landfill problem, as the bottom and fly ash is usually…. landfilled.

I’d love to see research into what happens with these chemicals when organic waste is used to create liquid fuels. It could be a solution for some waste streams, but its also possible it might just create other problems.

As for contaminated sites…. so often the solution (and I used to work in this sector) was to dig the crap out and…. landfill it. Bioremediation has lots of potential, but its quite rare for landowners and developers, or indeed regulators, to have the patience to see if these systems work. Dig and dump is simply easier. Very often, the only real solution is to accept its there and focus on stopping it getting into the food/biology chain.

I used to go to the Common Ground Fair run by MOFGA, Maine Organic Farmers Gardeners Association in the 1990s. I hope they are still the independent, vibrant organization they were then.

“…the mulch I got from the landfill operator was one of the ickiest substances….”

The waste recycling racket is Global, billions upon billions with much of that money coming from Regulatory Capture aka taxes. One of the principals of recycling is that if it costs too much money to separate out the low,no value from the value then you do not do it. In my rural area, they drive huge diesel trucks around long stretches of empty roads to pick up a few bins of God-knows-whats-in-it garbage and then drive that to a center to be composted. They may try to separate some of it but not much.This “compost” then goes Lord knows where, on what and for what purpose.

You can read Giants of Garbage for a primer on the Global Recycling Rackets. I read it way back in 1993. It is a great template to view how racketeering has become Globalized, something to keep in mind while living through Global Covid.

Don’t forget about PFAS in take-out food packaging, including “compostable” alternatives to styrofoam and plastic.

There is a LOT of R&D that needs to be done regarding water purification in general, and PFAS in particular. For example, I don’t see any institutional support whatsoever for point of use purification. As a practical matter, it will be never before everyone is connected to a central water grid, and even that is not always safe, hence the need for POU. Many technologies that work at this level would also be scaleable to municipal.

Whose job is it to do this R&D? Large companies that devote all their money to buy back stock? Government agencies with puny R&D grant offerings adminstrated by mostly civil engineers?

Two suggestions:

NEVER NEVER use sewage sludge as a soil amendment. Humans, who are at the top of the food chain, are quite capable of concentrating contaminants then delivering the contaminants via excretion . If memory serves even the White House vegetable garden developed by Mrs. Obama was found to be contaminated with sludge from the local water treatment plants.

Are products (e.g. Scotguard) created by advertising really needed ? Particularly when the by products or even the products themselves are forever chemicals ?

> NEVER NEVER use sewage sludge as a soil amendment.

Amen.

> Are products (e.g. Scotguard) created by advertising really needed ?

No.

A quick clarification about the WBUR description of PFAS as “linked chains of carbon and fluorine.”

This could be taken to mean that the carbon and fluorine atoms alternate in the chain – they do not. A better description would be “chains of carbon atoms most of which have fluorine atoms attached to them, instead of the hydrogen atoms normally sound in hydrocarbons.”

I’ve recently read that these compounds are used in the fracking fluid used for gas and oil extraction and that fracking is a major source of contamination. The use of these compounds for fracking was approved by the EPA under Obama.

I briefly looked into PFAS after I came across this article on marine (fish and shellfish) contamination. I went to find information on toxic dose levels, but I did not find much, and most are concerned with water supply levels, not food, and even then the literature is few and far between. I was unsure about website I linked as their claims were outrageous and their source was their own study, but a webengine search pulled up this as well. In their results, the highest PFAS level was 22 ppb, with most samples having trace levels of ~0.02 to 0.08 ppb. Conveniently they are in ppb, not ppt; 22000 ppt maximum, with trace of 20 ppt to 80 ppt. Insane. Some rational behind the broad range has to do with PFAS hotspots, particularly around military bases, industrial dumping sites, and in firefighting foam (AFFF).

Apparently the FDA doesn’t consider food a toxic source, but the EU has a recommended limit of 4 ug/kg body weight/week or 4 ppt/kg/week from food. Even so, from a cursory glance the guidelines are all over the place and loose overall as even trace amounts may have health affects. For instance, even though the EPA has a suggested limit of 70 ppt for drinking water, here in NY it is 7 ppt. It would seem best to err on the side of caution, but what can you do? The stuff is ubiquitous now and nobody really knows what it does and at what dose.

Anyone know by some states are so thickly blue dotted in that map and others are not? Are some places

More studied? I’m in NC, so extra curious.

It seems to track well with proximity to paper/pulp mills and major military installations.