Yves here. I hope readers share my taste for studies of historical economic/social phenomena that had a lasting impact. How much of the much touted US/British “special relationship” is due not so much to (exaggerated) shared culture, versus an increase in personal connections at the top of the food chain due to intermarriage?

One part of this equation that was new to me was that nouveau rich Gilded Era Americans were aggressively shunned by old money. In the 1980s, the bond market and private equity new money had no trouble being welcomed by doyennes of New York society like Brooke Astor. They admittedly had to observe certain forms, like decorating tastefully and giving money to the right charities.

By Mark Taylor, Dean and Professor of Finance, Olin Business School, Washington University in St Louis, USA; Research Fellow CEPR; Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution. Originally published at VoxEU

The late 19th-century decline in British agricultural prices shrank the incomes of aristocrats and of land-owning ‘commoners’ as well. To carry on the tradition of raising money through auspicious marriages, British aristocrats looked across the Atlantic – to US heiresses with large dowries but no pedigrees, even by the standards of their own country. This column examines the social and economic forces that steered the daughters of US business magnates into marriages with British aristocrats.

Earl Grantham: Do you think she would’ve been happy with a fortune hunter?

Countess Grantham: She might’ve been. I was.

Downton Abbey, Series 1, Episode 1

Lady Cora’s mild rebuke of her husband’s hypocrisy in the opening episode of the popular international television series Downton Abbey (Fellowes 2012) is designed to remind him that it was the handsome dowry she brought from her native industrial Pittsburgh to rural Yorkshire to marry into the British aristocracy in the 1880s that saved the eponymous stately home and Earl Grantham’s family from financial ruin. This fictional storyline is based on a real-world trend. In the four decades before the outbreak of WWI, 100 daughters of US business magnates married titled members of the British aristocracy (Montgomery 1989, De Courcy 2017). Calculated another way: “Between 1870 and 1914, fully 10 percent of [male] aristocratic marriages followed this novel pattern” (Cannadine 1990). Given that the British aristocracy was generally regarded as the most exclusive club in the world outside of the British royal family, this is a remarkable phenomenon.

The premise of my recent paper (Taylor 2021) is that the rapid decline in British agricultural prices in the last quarter of the 19th century, which shrank not only the income of aristocratic landed estates but also the income of ‘commoner’ (i.e. non-aristocratic) families who owned land, led to a significant proportion of male aristocrats marrying American heiresses with rich dowries as substitutes for the traditional source – namely, brides from British families with landed estates but no titles.

British agricultural prices began their drop in the mid-1870s for several reasons, from the development of US railroads and prairies to the advent of steamships, all of which led to the UK market being flooded with cheap prairie wheat. Meanwhile, in the US, high society shunned the families of the newly rich businessmen making their fortunes during the Gilded Age. East Coast high society was the jealously guarded preserve of families who could trace their ancestry back to the earliest Dutch or English settlers, and who socially ostracised the nouveau riche business magnates and their families. So, what were these newly rich families to do? They married into the British aristocracy as a means of establishing a social pedigree, whatever the cost.

The trend likely started with the 1874 marriage of Jennie Jerome, the daughter of New York financier Leonard Jerome, and a younger son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, Lord Randolph Churchill – a union that produced Winston Churchill. Leonard Jerome settled a dowry of £50,000 on the marriage (about $6.5 million today). Two years later, Consuelo Yznaga, the daughter of Antonio Yznaga – who had made his fortune in West Indian sugar plantations before relocating to Newport, Rhode Island – married the heir to the Duke of Manchester, thereby proving that the highest social rank below royalty was not beyond the scope of an American business family’s daughter. The dowry settlement was £200,000 (about $26 million today).

Perhaps the most celebrated (or notorious) American-aristocratic marriage of the period took place at the height of the trend, in 1895, when the family of the US railroad magnate William K. Vanderbilt became allied to one of Britain’s most prestigious aristocratic families with the marriage of his daughter Consuelo to the 9th Duke of Marlborough. The dowry settlement was $2.5 million (about $82 million today), money that restored the family fortunes and, quite literally, the palatial Marlborough ancestral seat of Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire.

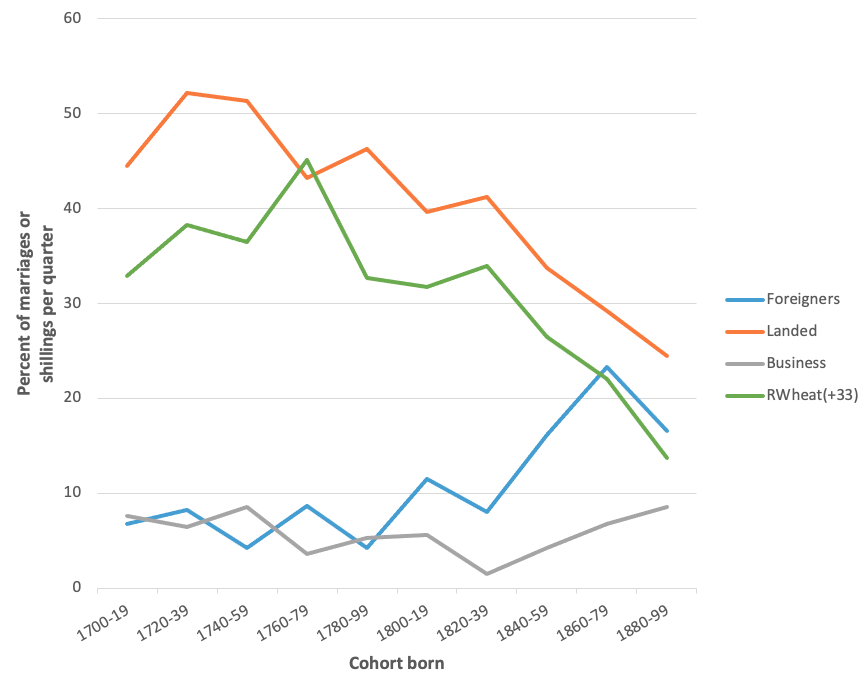

Figure 1 shows the percentage of marriages between British aristocrats and non-aristocrats (‘out-marriages’) for British males born in 20-year cohorts between 1700 and 1899, as well as the 20-year average real price of wheat in London 33 years later (33 being the average age at which British aristocrats married during the 18th and 19th centuries). The positive correlation between the decline in the price of wheat and the percentage of brides from landed families marrying into the aristocracy is striking, as is the rise in the percentage of ‘out-marriages’ to foreigners as wheat prices fell.

Figure 1 ‘Out-Marriages’ of the British aristocracy to foreigners – and of British ‘landed’ and business families – and the real price of wheat

Note: The series for the percentages of ‘out-marriages’ of male aristocrats to daughters of foreigners and of British landed and business families are from Thomas (1972). The series RWheat(+33) is the average real price of wheat in London (shillings per quarter; deflated by the consumer price index) for 20-year periods corresponding to the birth cohort periods but 33 years later; thus, for example, the observation for 1740–1759 is the average London real wheat price for the period 1773–1792, corresponding to the average real price of wheat during the likely years of marriage of the cohort born from 1740–1759. Sources for the wheat price data are Clark (2004) for 1700–1769, and Solar and Klovand (2011) for 1770–1914; the source for the CPI data used to deflate the wheat price series is Clark (2018).

In my research paper, I use simple probability theory to demonstrate that the likelihood of these correlations appearing purely by chance over these long periods is miniscule. I also show that aristocratic marriages to US heiresses were part of a wider, less pronounced phenomenon whereby non-American foreign brides were also substituted for British non-aristocratic landed brides during much of the 19th century, when agricultural prices declined. In addition, I find significant evidence of substitution for landed brides with British business family brides over the whole of the 18th and 19th centuries; as shown in Figure 1, this trend is less marked than the rate of admission for foreign brides, but it nevertheless increased over the course of the two centuries.

In economic theory terms, these results are consistent with a form of ‘positive assortative matching’ in the marriage market (Becker 1973), supplemented by a lump-sum transfer to the bridegroom (i.e. a dowry, see Becker 1991). During a period of agricultural decline, there may be cash constraints on lump-sum transfers from landed families just when landed aristocrats need money most, allowing unlanded but rich families to offer higher lump-sum transfers in order to compensate for the lower level of prestige associated with non-landholders – a phenomenon that may perhaps be termed the ‘Downton Abbey effect’.

See original post for references

Just hopping in to recommend the 1990s miniseries based on Edith Wharton’s unfinished final novel about this phenomenon, The Buccaneers.

Except for the 1990s vintage happy ending, it captures what the human side of this must have been like. In particular, the risk of a Wall Street fortune being lost and the dowry (paid in installments if the miniseries is to be believed) falling through.

Yes, Edith knew a thing or two about the Noveau Riche. She was very much a Manhattan/Newport girl and her “crowd” were all the fodder for her novels. Newport fell into steep decline after the revolution what with the British burning half the town and the curbing of the triangle trade. Having no ladder to climb in the circles of the Olde Riche, Mrs. Astor and her cohort set up in Newport and precipitated its revival, only to have the stock market crash of ’29 send the place back into oblivion. Of course you can’t keep an overwhelmingly beautiful place down, and it is currently sinking under the weight of day trippers, wedding parties and a rising tide. Ob-la-di, ob-la-da. Edith would chuckle if I told her that three things things still thrive in Newport…mold, fungus and social climbing.

Newport has been a Navy town, site of a boot camp for many years most importantly during WWI, WWII, and Korean War. In addition, the Torpedo Station was established after the Civil War and remains an important naval laboratory. But a big hit came after Viet Nam in the drawdown when the cruiser/destroyer fleet was relocated to Norfolk, leaving Newport as somewhat of a ghost town.

Never made the connection but I am sure that what the author of this post – Mark Taylor – is quite correct. There was a major slump in agricultural prices in the UK due to the effect of all those massive wheat fields in North America coming online and that could be transported across the Atlantic by the new generation of steamships. Looked up the figures and confirmed that ‘Between 1809 and 1879, 88% of British millionaires had been landowners; between 1880 and 1914 this figure dropped to 33% and fell further after the First World War.’ The problem became twofold. The agricultural depression mean that British workers either had to move to the big cities for work or else emigrate overseas. I happen to know that Wiltshire was severely hit by this effect. For the landed gentry, this meant a decrease in rents and the like which were a source of their wealth even though they still had capital-intensive estates to run. Here is a page I looked up talking about the background to this Great Depression of British Agriculture-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Depression_of_British_Agriculture

With crunch-time approaching an infusion of wealth was needed. Younger sons may have still gone into the Army or the Clergy but the eldest sons needed wives – rich ones. And there were not that many to be found in the UK. Enter what came to be know as the “Dollar Princesses.” The parents of Lord Randolph Churchill were certainly appalled that their son would marry a tattooed American girl whom he had known for only three days but after they ran the numbers they agreed on accepting them. Not only did this union produce Winston Churchill as this post mention but it also made it more acceptable for this to happen. The following page shows how may of the “Dollar Princesses” there were-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_American_heiresses

And the next page shows that this happened so frequently, that there was a publication for them that listed them, still unmarried men, their titles as well as their reputed fortunes-

http://www.edwardianpromenade.com/women/titled-americans-1890/

Many in the English upper class were drawn to gambling. That vice, among others, compounded the challenges in maintaining their expensive, er, lifestyles. Estates to maintain, fashions to wear, mistresses to pursue, an exhausting regimen.

Thank you, Q. You forgot the horses, ideally fast and bred in the purple.

Around here, the Rothschilds bought the Churchill estate, Waddesdon, in the mid 19th century and the Astors bought the Sutherland estate, Cliveden, in the 1930s.

One part of this equation that was new to me was that nouveau rich Gilded Era Americans were aggressively shunned by old money.

Good Lord. There’s this guy who writes for this site who uses the pseudonym Lambert Strether — perhaps you’ve seen his byline here? It comes from a character of the same name in Henry James’s novel THE AMBASSADORS. That novel — and pretty much all of Henry James’s significant longer work is about exactly this theme — of alliances between American New Money and impecunious Old World aristocracy — and the repercussions thereof.

Indeed, the theme is all over canonical turn-of-the-20th-century American novelists like James and Wharton (and echoes on into works like Fitzgerald’s GATSBY). Something that Harvard Business School didn’t cover, I guess.

In particular, Henry James is considered by many America’s greatest novelist. Not me, and I find THE AMBASSADORS a bit of a long-winded bore. But James’s THE WINGS OF THE DOVE and THE GOLDEN BOWL are worth reading.

THE WINGS OF THE DOVE, in particular, is amazing because by way of a very polite, mannered Victorian-Edwardian style that never says things outright, it goes to some singularly dark, heartbreaking places I’ve never seen another novel go to —

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Wings_of_the_Dove

To be clear, I read plenty of 19th century history and literature. I did not say “shunned”. I quite deliberately said “aggressively shunned.”

There is a big difference between posturing that you hate the presumed tacky rich and still on the QT consort with them. And let us not forget that the robber barrons of the 1860s, the fur traders (as in the Astors in particular) were pretending to be old money by the 1890s. So old money was awfully thin.

And America did not have Old World aristocracy, fer Chrissakes. To the extent it had actual vintage money in the 19th century, it was mainly whalers and slave traders (who managed to keep their lucre, unlike most slave owners; one of my old money friends from New Orleans says his family ran rum during the Civil War, which I am pretty sure means they were slave or triangular traders before and changed their business model). I have depending on which genealogy you believe at least 7 and perhaps 11 ancestors who came over on the Mayflower, when only about 110 survived, so I have some knowledge of this territory. Old money American pretenses are just that, pretenses. Go read de Tocqueville on that. He made clear everywhere he went he found hustlers.

Nothing I disagree with here — or in the comments. But we should be equally sceptical of the pretensions of the English aristocracy too. They were recruited generation after generation from moneyed men and London lawyers. You don’t have to dig very deeply into the fancy genealogy of any snooty aristocrat to find nouveau riches who bought their way into noble status by services to the crown. Check out any old noble family, peel away the fancy titles and find the roots in business and grift. The British upper classes were always hustlers with their sticky fingers in the public purse. There’s some good material on this in Piketty.

And how, we should ask, did they get their hands on all that land? By state-sponsored theft on a gigantic scale. The Empire begins in the brutal dispossession of the population “at home.” Marx’s chapter on “so-called primitive accumulation” in Volume 1 of Capital is always worth rereading.

Thank you, Count Zero.

Having gone to school with and worked for and with the upper class, I reckon Piketty underestimated the scale of that hidden wealth and failed to address how it is connected and protects and perpetuates itself.

Further to your comments about Blair and Connaught Square last week, I live near his Buckinghamshire estates.

In the past year, the family have let the flora grow, so that us peasants can’t complain about their Leona Helmsley attitude to lockdown.

I agree with you about the pretensions. There weren’t that many companions with William. Much of the aristocracy made money in the City like the Boleyns and sheep farming like the Spencers in the latter part of the Middle Ages.

Aye Colonel, in a couple of generations there’ll be a Blair standing next to William the Conqueror as the prow grinds into the Sussex shingle. It might even be on the escutcheon of the Duke of Baghdad, scion of a noble line.

This seems relevant:

Henry James, indeed.

Here is Wilde’s well-known passage in The Picture of Dorian Gray—

. . . Lord Henry shook his head. “American girls are as clever at concealing their parents, as English women are at concealing their past,” he said, rising to go.

“They are pork-packers, I suppose?”

“I hope so, Uncle George, for Dartmoor’s sake. I am told that pork-packing is the most lucrative profession in America, after politics.”

“Is she pretty?”

“She behaves as if she was beautiful. Most American women do. It is the secret of their charm.”

“Why can’t these American women stay in their own country? They are always telling us that it is the paradise for women.”

Among other reasons, all this is why I don’t believe there is much “old money” left. American old money is especially funny. Paul Fussel’s book is so terribly dated that even its ideas from the 1980s are absurdly quaint now, but I didn’t take his old money talk very seriously even then. Then again, I don’t see the Brit royal family, e.g., as anything but nouveau riche either at this point. The money and loot might indeed still be partially old, but the people?

Our world has been Borg-assimilated by nouveau trash, and they design it in their image, which is why it looks uglier and uglier, and why there are right now absolutely *zero* world famous painters or sculptors or architects or composers of the 21st century, now one-fifth of the way into it (with apologies to – what? – Banksy, the great Hunter Biden, and the various awful film score composers out there). It is also why there is zero talk of litter, not even from the left, when there should be. Litter, although trash by definition, is free advertising, and so totally acceptable to allow by the nouveau and a non-issue.

Theme of the NR: If we can make a buck off it, then we do mass implement it, and I do mean now now now, and damn what it looks like or does to nature. Form follows function, baby. How is any old money different these days? They’ve all hooked into this. The multi-generation cathedrals of the 12th c. are now entirely in the form of technology and commerce.

I hope the good Col. Smithers chips in on this.

This weekend I was visiting the somewhat overblown but still impressive Kylemore Abbey in County Galway, which pretty much encompasses this social history. It was built in the 1850’s, at a time when the Irish aristocracy was already in steep decline due to falling wheat prices (not just the corn laws, also due to rising productivity in Europe in the aftermath of Napoleons defeat at Waterloo). The house was constructed by the first of the new wave of nouveau riche, Henry Mitchell and his (I think) somewhat higher born wife. His family made their fortune in cotton trading. Although non-titled English, they quickly settled and he became an MP and ardent championof Irish independence and the rights of the peasantry (which didn’t extend to him giving them any land, but whatever). It was not uncommon for wealthy British or others to buy estates in Ireland as a cheaper way of playing the aristocrat – at least one hedge funder ennobled by David Cameron tried the same trick in the last few years.

When Kylemore was sold up it was bought by the Duke and Duchess of Manchester. The Dutchess was a Zimmerman from New York and brought a vast fortune with her, which her husband promptly squandered. Hence it fell into the hands of the Grand Irish Dames of Ypres as the Benedictine Nuns of the time were known.

Marrying out was, if anything, more common with the Irish than the English aristocracy. The old catholic aristocracy in Ireland frequently married to old French and Spanish families in the 18th Century in order to maintain some social standing relative to the anglo-Irish, but more importantly to maintain trade relations – hence so many French wine houses (such as Hennessy Brandy) has Irish names. Sometimes it worked in reverse, with those on the fringes of the aristocracy marrying into impovrished eastern European families in order to gain title, the Countess Markievicz being a famous example.

The Irish anglo-aristocracy faded before the English as the decline in food prices hit Ireland harder and earlier as grain production moved to more suitable climates – the advantage Ireland had in having vast armies of cheap labour became redundant when relative peace hit Europe. They started with marrying into English nouveau riche, then Americans. Currently, Chinese are favoured (Downton Abbey is immensely popular in Asia) – the current Earl of Rosse, part of the incredibly talented Parsons family is now married to a Chinese lady.

These levels of society are well above me, but I strongly suspect Yves is right that the historic family links between the upper crust of London and New York societies is an important driver in the closeness of those establishments. I’ve always suspected that this was part of the reason FDR appointed Joe Kennedy as ambassador to the UK in 1938 – sending a rich Irish catholic with a dubious background there was an amusing way for him to annoy the traditional upper scions of both Boston and London.

I’m surprised that the repeal of the Corn Laws (1846) and the Reform Bills (1832, 1867) are not mentioned here, since they were crucial to this process. The former by exposing British agriculture to foreign producers (especially in North America) and the latter enfranchising the merchant classes and urban industrial labour. Both of these were factors in the demise of the rural landlord class.

No tears for that lot from this quarter, mind …

Good points — but the merchant classes (& many craftsmen, artisans, farmers) always had the vote stretching back into Stuart and Tudor England. 1832 was about rationalising a very messy electoral system and bringing it into line with the interests of property — landed, commercial, industrial (which overlapped). So 1832 ensured that elections were more efficiently managed.

1867 was a daring strategy to incorporate skilled workmen into a manageable electorate.

Hiding rentier activity in the economy does have some surprising consequences.

We got Ricardo’s Law of Comparative Advantage.

What went missing?

Ricardo was part of the new capitalist class, and the old landowning class were a huge problem with their rents that had to be paid both directly and through wages.

“The interest of the landlords is always opposed to the interest of every other class in the community” Ricardo 1815 / Classical Economist

What does our man on free trade, Ricardo, mean?

Disposable income = wages – (taxes + the cost of living)

Employees get their money from wages and the employers pay the cost of living through wages, reducing profit.

Employees get less disposable income after the landlords rent has gone.

Employers have to cover the landlord’s rents in wages reducing profit.

Ricardo is just talking about housing costs, employees all rented in those days.

Low housing costs work best for employers and employees.

Who pays?

It’s the right question, but we keep getting the wrong answer with neoclassical economics.

Employees get their money from wages and it is employers that are paying, via wages, reducing profit.

Everyone pays their own way.

Employees get their money from wages.

The employer pays the way for all their employees, via wages, reducing profit.

No wonder all our firms are off-shoring.

Capitalism actually works best with a low cost of living, but no one can see that with neoclassical economics.

It’s rentier economics and it works.

The rentiers gains push up the cost of living, so this has to be hidden.

What then, when the rentiers own the capital, and the housing?

I’m waiting for Col Smithers here, who’s a walking encyclopedia on these things :).

a really fascinating book abt the dollar princesses is, well, “the dollar princesses” by ruth brandon.

Thank you Yves for this link into the economic forces behind this phenomena. The article segues nicely with my current reading list. I was going to start reading Mrs. Osmond by John Banville last month and decided to read Portrait of a Lady by Henry James first. Mrs. Osmond is a continuation of the James novel and I felt reading Poitrait was a prerequisite for understanding the latter. Henry James is a fine author but he dives too deeply into the thoughts of Isabel Archer (Mrs Osmond) and the social mores and restrictions of late 19th century England for my taste. I skipped the middle part of the novel as it was much too discursive for my enjoyment. I have read elsewhere this phenomena of exporting brides with large doweries to British aristocrats seems to have stopped around WW I. Perhaps the English Lord’s finances were rescued by war profiteering and they no longer needed to resort to fortune hunting.

I believe Trollope was one of the first on the case, in “The Duke’s Children”, one of his last novels (1879) and the culmination of the Palliser series. Lord Silverbridge, eldest son of the Duke of Omnium, falls in love with an American heiress, Isabel Boncassen, whereas the Duke had hoped his son would marry Lady Mabel Grex…

I was just going to comment on “The Duke’s Children!” A wonderful novel–like all Trollope’s work.

Yves does it again. The combustible mix of the children of the nouveau riche and the children of the downwardly mobile inheriting class is always fun to watch.

My family were Catholic Irish immigrants of the lace curtain variety. I eventually realized, cutesy of 23AndMe, that I was 100% English, probably the descendant of the Anglo-Irish invaders who were to dumb or stubborn to join the Cromwell side. So they ended up as dirt-poor Irish Catholic hill people… with a few pretensions. Yves, I gather, comes from a long line of New England people who ended up marooned in Alabama because that’s where the money was to be made; the Cabots and the Lowells meet Scarlett O’Hara and Rhett Butler. Lambert? Who knows; he isn’t talking. People who view the world from the outside often develop a fine nose for social reality.

The English aristocracy was already in a slow crisis in the late 18th century; too many children, too few resources. Read any Jane Austin novel to see the results. The grain of the Russian empire was already flowing out of Riga to England in the 18th Century but that got cut by the wars of the French Revolution, a real food scare from 1793-1815 while the population of the British Isles was growing. The Corn Laws (corn meant “seed”- it was about rye and wheat) restricted the foreign import of foodstuffs… and kept the gentry well off for a while.

And in the US? Mrs. Vanderbilt always entertained at home; the new rich didn’t have homes of her scale so they “dined out”, what she called “Cafe Society”. Old Mrs. V was actually smart and pragmatic; she once remarked that she didn’t care what people did in private as long as “It didn’t scare the horses”. The first time she accepted an invitation to “Dine Out” it was a social earthquake.

The Parade continues. Literary and cultural celebrities like Warhol mix with the old downwardly mobile (Edie Sedgwick) while the children of good breeding wind up banging female business leaders, rock musicians and… gasp… Jews and Black Basketball players. God, NYC was fun in the 1970s… and DC at least used to have a seriously frivolous underground.

Starter wives (and husbands) are given a good settlements to go away (the modern versions of remittance men). The replacements are smart, cute Chinese girls, even cuter, gay Brown grad students from the Middle East and EuroTrash. You don’t even want to ask about swim coaches, priests and rabbis, and the press… Positive ions float around and always seem to find the negative charges. Beauty and brains conquer power, breeding and money. The parade goes on.

I wouldn’t trust 23andme or any of those other DNA-ancestry services. People have gotten different regions and sometimes different continents on different tests from different companies and even the same company.

Not to mention losing control of that one last bit of personal information.

The next disaster is the free trade agreement with Australia. The landowners will be stuffed before the trade deals with the US and Brazil.

One hopes Synoia and R / rtah 100 chime in.

I cannot add much to the story of Dollar Princesses but reading the post and the comments makes me realise how much British social history can only be acquired by living among the natives because it isn’t written down. I don’t just mean Colonel Smithers’s brilliant join-the-dots exposes on who is married to whom in high society. I mean the deep structure of society, on which the posts on “American gentry” have been so interesting about the USA. All politics is local….

Some background that might provide useful context for non-natives would be:

1) the aristocracy is a social rank, or rather the top five social ranks of the peerage: dukes, marquesses, earls, viscounts and barons. Until the Parliament Acts ended the ability of the House of Lords to block legislation from the House of Commons, they were literally the ruling class as their titles entitled them to sit as peers in the House of Lords. Many of them were great landowners with thousands of acres but some of them had only hundred and some were poor as church mice. Even today, the tabloids regularly delight in the story of another binman inheriting a peerage.

2) Below the aristocracy are the landed gentry – comprised of baronets (hereditary knights) and the aristocracy’s second sons etc. and their wives. These are also known as the squirearchy, the local squires or lords of the manor. Every village would have a squire but not necessarily an aristocrat (there is an area of the Potteries, the heart of the pottery industry, with five dukes, nicknamed the Dukeries). Below the gentry came the yeomanry – hence, the yeomen of the guard – the class of farmers who owned their own land but had no title. Below the yeomanry is the peasantry, the landless labourers and tenant farmers. Primogeniture and male succession to titles meant the second born son would slip down the scale whereas a daughter might climb up. Poor gentry cheerfully married wealthy yeomen for their land; rich gentry married poor aristocrats for their title. The Duke of Westminster literally wouldn’t be half as rich if an ancestor had not married the daughter of dairy farmer whose farm happened to be where Chelsea and Belgravia are today!

3) The other way up in life was to be the equivalent of the French noblesse de robe, to be a member of the then PMC, usually as a lawyer or holding an office of the Crown, and gain a title for service at Court. The clergy represented a spiritual version of the same track, to hold high office in the Church. Cardinal Wolsey is a good example but also the great Elizabethan lawyers (all bizarrely from the Westcountry) like Grenville. Newton and Pepys are other good examples. And there are endless soldiers and admirals cluttering up the peerage, the Duke of Wellington being foremost.

4) This has gone on for a thousand years, so you will find plenty of farmers in my neck of the woods who can trace their ancestry back to the Normans, even trace their farms back to the Domesday book, without having “bettered” themselves and yet who consider the local squire to be “new money” because he acquired his title/estate, depending on the century, with the Tudors (dissolution of the monasteries) the triangular trade, the nabobs or industry. Their children will then marry and honour will be satisfied. On another level, the Earls of Devon have a longer pedigree, by half a millennium, than the Dukes of Devonshire, who have no connection to Devon beyond administrative error because they were supposed to be created the Dukes of Derbyshire! You can begin to see why, in the shires, it is widely felt that the Royal Family are a bunch of arriviste Germans and not proper toffs at all. And in Scotland, a lot of lords line for a Stuart king….

5) the rents that supported the aristocracy and gentry are less directly barbarous than appears. The landlords often got their hands dirty, running the “home farm” in hand as gentleman farmers. Their tenants were rarely sharecroppers, in England at least – it would be bad for business. They were farmers employing men and women (as well as family) to run a business. Often, they would own their own land and rent more from the squire. Some tenants were richer than their landlords. The tenancies would often last for generations, as much through custom and sentiment as any protections. I won’t pretend the rural economy was a bed of roses but it was more feudalism than capitalism until WW1. The real victims of the rentiers were the landless labourers, who had been dispossessed of their feudal strips or fields by the enclosure movement of 17th and 18th century, driven by the well connected.

6) It’s not clear to me that aristocrats make great literature. It’s just one damn ball after another, like War and Peace. Fine for a soap opera like Downton Abbey but lacking opportunity for introspection. The best English novels are about the ranks below. Jane Austen is a chronicler of the rectory and the manor house, the clergy and decayed gentry – squeezed between the up and coming yeomanry (the Napoleonic wars were good for farming) and the aristocracy; a world away from the great estates. Wuthering Heights by contrast features a nouveau riche narrator, renting the local manor, recounting the story of Heathcliffe, a scion of yeomanry that went to the colonies and then went bad. The hero of Parade’s End by Ford Madox Ford is the second son of Yorkshire gentry, making a career in government service. Guy Crouchback in the Sword of Honour trilogy is Somerset gentry and a recusant (Catholic) to boot, throwing over a life of dissolution as a remittance man in Italy to fight for his country in WW2. Poldark is a story of Cornish gentry, with an occasional aristo bad hat thrown in.

Further to PK’s comment about the Duke of Manchester, it was a pity that the family’s Tandragee Hall in Northern Ireland and Cassiobury Park in Watford (sic) could not be saved.

An American heiress would have been fantastic for the most debauched aristocrat the school I attended produced, the third Baron Moynihan. They don’t make ‘em like that / him any more. Imagine that fellow in the House of Lords.

The French and other continental aristocracy did not need much American money. There were and are enough Rothschild, Lazard, David-Weill banking and Franco-Mauritian sugar baron heiresses to go around in France and desperadoes from Latin America for the Iberian peninsula.

As the global elite is and was small, a French banking heiress and descendant of Louisiana planter and confederate envoy Slidell was married to a grandson of Churchill, also called Winston.

Yes — but Jane Austen was not really writing about the aristocracy. Her subjects are a bit lower in the social hierarchy —mostly the middling and lesser gentry and their host of relatives desperately grasping for a living from a lucrative marriage settlement or from the army, the navy and the church.

Jane Austen’s characters are an ugly crowd of idle and uneducated parasites seeking an income from rent or from the state. Their contribution to British society of the day was merely to consume the value generated out of the labour of the vast majority while flouncing around imagining they were important — and preaching to their betters. Oddly, Miss Austen, who as far as I know never did an honest day’s work in her life, manages to omit all working people from her novels. They do not exist.

They were important! They kept the primary producers from consuming enough value not to need the aristocracy. Absent the systematic cruelty needed to enforce them, inequities tend to converge away. And that is the story of economics.

Interesting to consider the rise of the PMC coming out of this, particularly the rise in PMC occupations following about a generation later. The couples didn’t inherit the knowledge of domination, so they had to piece a science together…

Not sure I understand your first paragraph. The primary producers were the farm labourers, toiling for starvation wages — within sight of Miss Austin’s parlour window where she could sit sipping Chinese tea and eating a bun. Not sure how such activities kept labourers from consuming enough not to need the aristocracy. They didn’t need the aristocracy. They did need to consume more.

What do you mean “inequities converge”? You mean they get less? Well sometimes they do and sometimes they don’t — see incomes in the USA in the last 40 years. As for the story of economics: seems to me it’s either about giving clever and spurious justifications for exploitation or it’s about developing clever techniques for increasing profit.

By claiming a primordial right to the surplus generated by those primary producers and crushing their opposition, the elites made themselves appear necessary. Had Lady Austen and her manor house and those like them disappeared from history altogether, the lot of the men and women in the fields would be no worse, and most assuredly better.

US readers would be interested to hear that Washington’s distant relatives remain landowners in Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire. The first president is related to the Boleyn, Smith / Carrington (as in Lord Carrington and what became NatWest bank), Blunt (as in Anthony) and Mosley (as in Oswald) families.

Hamilton is related to Princess Diana, Hamilton dukes in Scotland and Ireland.

Al Gore is descended from the Gores of Lissadell, see PK’s comments about Constance Markievicz, and Harlech and Gore-Booths.

One can see why there’s some anglophilia in the US upper class. Add the monstrous regimen of Rhodes scholars. As a Catholic, I note that Buttigieg became an apostate and Anglican / Episcopalian at Oxford. One wonders if he recalls the memorial to what Mary did to such apostates in Oxford?

It hadn’t occurred to me that the Gores were related to the Gore-Booths. The latter (if local rumour is true) eventually in-bred themselves out of existence.

Thank you, PK.

Al Gore is descended from Sir Paul Gore, who went to Ireland. The Irish branch later became Gore-Booth. Sir David Gore-Booth was ambassador to Riyadh and Delhi and advisor to HSBC.

The British / Welsh branch founded HTV, the ITV franchise holder for Wales, and owns much of Shropshire and mid Wales.

For those who like reading more than they like scholarly tomes, Anne de Courcy’s “The Husband Hunters” is a pleasant book with which to read more on the subject.

I’m a bit curious about what the American incentive in this would have been. ‘Old Titles’, right, but why would an American care about that? Why would being part of some snooty European aristocracy be considered desirable? From what I’ve read the idea of a friendly US and Britain is a quite recent phenomenon, as in post-WW2 to a large extent. European aristocrats, and particularly British nobility, were genuinely loathed in the United States for much of our history. The United States birth was defined by a violent rupture with Britain. We fought them in a second round in 1812, and there was a serious possibility of them entering our Civil War on the side of the Confederacy. Genuine, deep-seeded animosity between the rising great power of the US, and the ’empire on which the sun never sets’ existed throughout the 19th century. Even WW1 and working together against the Germanic Hun wasn’t enough to fully mellow things; as late as 1939 the Department of War maintained a War Plan Red outlining offensive operations for war against the UK.

We only become completely normalized ‘allies’ after WW2, when the UK, kicking and screaming, became reduced to a US client state.

A British title was a status marker they could buy for money, like a very fancy house or boat.

A working class family does figure into the story line of Jane Austen’s novel Emma. Her friend Harriett is eventually married to a farmer, a Mr. Martin I think, who works on the land of Emma’s friend Mr. Knightley. One of the points of the story is the wisdom and, to use Austen’s language, felicity of the marriage. The famer’s family are portrayed as warm and wholesome people, who are held in high regard by Mr. Knightley.

Harriet Smith is of uncertain status — because she is “illegitimate” — but she is very far from being working class. She is never required to work and she marries a prosperous farmer. This is how she is described in the final chapter of EMMA:

“She proved to be the daughter of a tradesman, rich enough to afford her the comfortable maintenance which had ever been hers, and decent enough to have always wished for concealment. Such was the blood of gentility which Emma had formerly been so ready to vouch for! It was likely to be as untainted, perhaps, as the blood of many a gentleman.”