After last year’s economic carnage, the spectre of runaway inflation is the last thing the region needs.

As prices for many vital goods and services surge across the globe, central bankers in most advanced economies refuse to take their foot off the gas, even as inflation gets stickier. But things are very different in emerging economies.

Last year many emerging economy central banks slashed rates to extreme lows as economic activity ground to a standstill and inflation crumbled. But now many of them are frantically hiking them again as inflation returns with a vengeance, largely on the back of forces that are global in scope. They include low inventories, supply chain shocks, soaring shipping costs, labour shortages, extreme weather events, surging demand for certain commodities and consumer goods, and the huge monetary and fiscal stimulus programs still under way in most advanced economies.

Painful Memories

Latin America’s two largest economies, Brazil and Mexico, have respectively raised rates five times and three times so far this year. There’s likely to be more to come. Although rising commodity prices are largely welcome in the resource-rich region, most countries would rather avoid a return to runaway inflation, especially given the current weakness of their economies. In Brazil and Mexico anybody over the age of 35 can remember what life was like under high — or in Brazil’s case hyper- — inflation. They don’t want to go through it again.

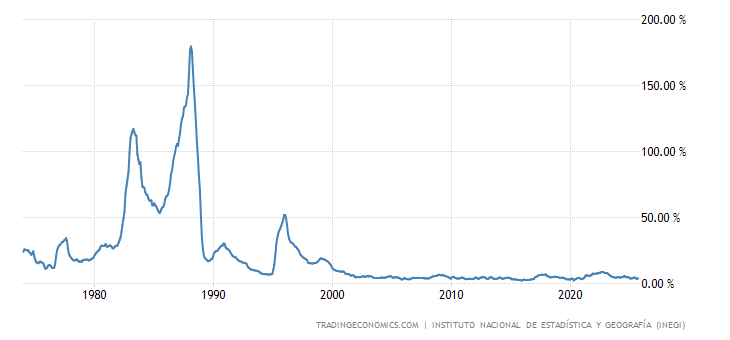

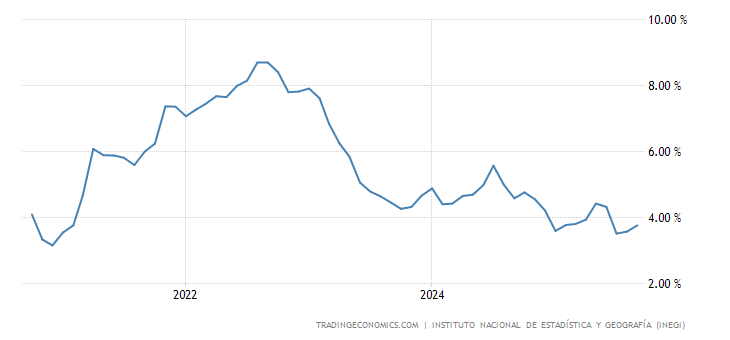

Mexico:

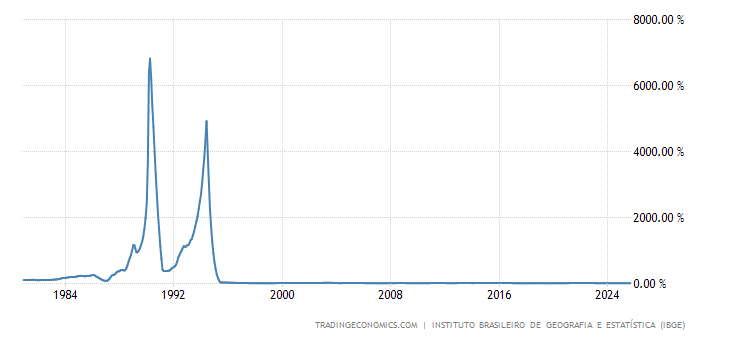

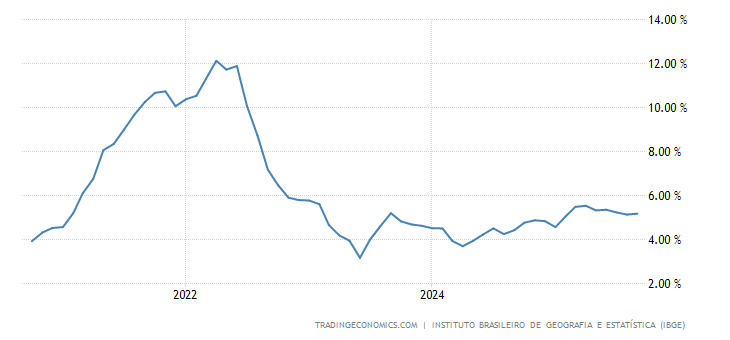

Brazil:

In Brazil today inflation rates have tripled over the past year, from 3.1% in August 2020 to an anualized 9.7% in August 2021, its highest level since 2016. In September, the IPCA-15 consumer-price index — a mid-month predictor of the official inflation rate — surged by 1.14% over the month. If the indicator rings true, Brazil will soon report its highest reading for the month of September since 1994. That was when the country had just launched a new currency, the Brazilian Real, after being ravaged by its second bout of hyperinflation in seven years.

Currency Movements, Extreme Weather Events

There are a number of reasons why Brazil is suffering particularly high inflation right now, even among its peers. First, the Real has fallen around 10% against the dollar since July. As in Europe, the country’s energy market has been battered by unexpected weather events, including its worst drought in almost a century. Reservoirs in the Southeast and Midwest regions, which account for nearly 70% of the storage capacity, reached near-record lows of less than a quarter full over the summer. The drought has fuelled higher prices not only for food, as domestic production of staples has fallen, but also of energy, since Brazil depends on hydroelectric power for around two-thirds of the electricity it consumes.

By July marginal operating costs of the Brazilian power system had reached their highest levels since 2015. And energy prices, as IHS Markit warned in July, are a vital contributor to inflation since they have an impact at each stage of the production and distribution chain:

Both wholesale prices and retail tariffs are therefore likely to result in higher production costs for companies operating in the manufacturing sector such as the production of automobiles, chemicals, and metallic products. Low water levels will also affect the agribusiness sector, which will experience reduced water supply for irrigation and impaired movement of cargo through waterways.

By the end of August producer inflation had increased by 23.5% year-to-date. All activities monitored by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) registered price increases in August. The fact that prices are surging so fast at a time when the economy appears to be stagnating — it contracted by 0.1% in the second quarter — is of particular concern, raising the spectre of stagflation.

In Mexico, inflation is not quite as high as in Brazil, partly because Mexico’s central bank, Banco de Mexico (Banxico for short), didn’t cut rates as aggressively as most of its peers last year. AMLO’s leftist government also didn’t unleash nearly as much fiscal stimulus as its right-wing Brazilian counterpart. Nonetheless, the consumer price index (CPI) in Mexico still weighed in at 5.59% in August, almost double the central bank’s target rate of 3%.

Banxico raised its benchmark policy rate by 25 bps to 4.75% last week, saying that while it expects the shocks fuelling inflation to be transitory, they may still pose risks to the price formation process and to inflation expectations, due to their variety, magnitude and potential duration of their effects.

Core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices and is widely considered an accurate indicator of long-term trends, rose 0.43% in August, its highest rate since 1999. Overall consumer price inflation is expected to top 6% in September, says Banxico’s deputy governor Jonathan Heath, who expects inflation to continue rising until at least January or February 2022.

Prices are also rising fast along the Andes. In August, Colombia’s consumer price index (CPI) clocked in at 4.44%, its highest level since 2017. Chile’s CPI reached 4.8% in August, its highest reading since late 2016. In September, Peru recorded its fifth consecutive month of rises, as its CPI surged to 5.23%. The last time it was that high was February 2009. All three countries have begun hiking rates in the last month.

The High Price of Tightening

But tightening monetary policy comes at a price. Raising rates risks squeezing even more life out of economies that are still on their knees after last year’s myriad shocks. It will also make it harder for heavily indebted businesses and consumers to service their debts.

Even before Covid, many of these economies were already in deep trouble. Mexico was just entering recession while Brazil was still recovering its longest recession in history (2014-17). Chile and Colombia had been rocked by massive social protests over economic inequality. With their weak currencies and limited fiscal arsenal, many LatAm countries were not able to provide the sort of financial support programs rolled out in more advanced economies. But they still took on a lot of new debt that will be difficult to pay back.

Between 2019 and 2020, public debt in Latin America grew by ten percentage points, from 69% of GDP to 79%. At the same time, the region’s GDP sank by 7% — the worst contraction of any region tracked by the IMF. By the beginning of 2021 GDP levels in the region had slumped to levels not seen since 2011. In effect Latin America lost a full decade of economic progress. It shed more working hours than any other region, suffered more than twice the global average loss of income, and accounted for close to a third of all jobs lost globally.

Venezuela is still in the midst of a humanitarian crisis, which is hardly helped by the economic war the US is waging against it. Caracas just launched its third new currency of this century, the so-called digital bolivar, lopping off 6 zeros from the previous iteration. The economy of Argentina, another chronic invalid, is finally growing again after three years of recession. But inflation remains just over 50% and the country is still locked in negotiations with the IMF over the conditions of its next debt restructuring.

IMF Offers Limited Help

To boost global liquidity and help struggling economies, the IMF recently unveiled a new $650 billion allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), $44 billion of which went to LatAm countries. It’s a lot better than nothing but still not much compared to what has been lost. Sixty percent of the newly created money went to high-income countries. The US alone received 17% of the total despite the fact it can essentially print its own money at will.

One of the biggest threats facing Latin America (and the world at large) is surging food inflation. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO)‘s monthly Food Price Index, global food prices were up nearly 33% in August 2021 compared to a year earlier. The biggest price increases were seen in meat (22%), wheat (43%), barley (36%) and vegetable oil (60%). Average prices overall are now at levels not seen since 2011, on the eve of the Arab Spring.

To compound matters, these price rises are happening at a time that millions of people have been pushed out of work and into poverty. In 2020, moderate and severe food insecurity affected 40% of the population of Latin America and the Caribbean, 6.5 percentage points more than in 2019, according to a study by World Vision International, a Christian relief, development, and advocacy organisation.

To try to keep rising prices at bay, central banks in Latin America are hiking rates as fast as they can. But their effect is likely to be limited given that the pressures stoking consumer price rises are largely global in scope.

Nick Corbishley wrote:

What percentage of this new public debt is in a given country’s own currency? What percentage is in a foreign currency such as the US dollar?

Most LatAm countries do tend to issue quite a lot of their debt in dollars and it’s been the cause of lots of problems over the years. Countries with weak economies or currencies, of which there are plenty, tend to have little choice in the matter. Since the virus crisis began there have been, to my knowledge, six defaults on foreign currency-denominated bonds. Ecuador was first, followed by Argentina, then Suriname, Belize, and Suriname twice more. These countries will not be able to issue local currency-bonds for some time to come, I imagine. The region’s largest economies, such as Brazil, Mexico and Chile, also regularly issue dollar or euro-denominated bonds though most of their funding is in local currency. In the case of Brazil local bonds account for around 90% of sovereign debt; in Mexico, it’s around 70% and in Chile it’s around 75%.

Maybe El Salvador will be the first bit-coin denominated default…. :-)

Austerity – a tool used by the FIRE sector and the IMF to direct and coerce any that try to break the neoliberal free-market ideology.

In the USA – they bribe and pay to install their minions in congress and legislatures throughout the land to bring the mass of people to their financial knees, yet the only benefactors are the monopolists, oligarchs, the military industrial complex and predators doing ‘gods work ‘.

They have wrought misery and death throughout history, present the biggest danger to democracy, to freedom, to life on earth. Through years of blind greed and avarice, they perverted our constitution in ways they could not know and, yet, they are now bound by their laws and their positions to continue this course or face lawsuits, sanctions and liability upon fiduciary duties. The system of laws and taxes they have blindly and innocently conspired to develop have placed humanity, liberty, life, freedom and democracy at risk.

Now- two huge, easily affordable plans – hung up without content – to be diced and sliced by the vested interests through their minions in congress – the same minds that brought us the 2008 financial crisis and the same interests that knowingly caused environmental harm globally, the same interests that caused all famines to date, the same interests responsible for the genocide of hundreds of species on this planet, the same interests responsible for the fall of other democracies throughout the ages —

When will the news cover the doings and harm the FIRE sector is doing here and now and into the future?

RANT Done – I apologize —bla bla bla TINA not.

>>AMLO’s leftist government also didn’t unleash nearly as much fiscal stimulus as its right-wing Brazilian counterpart.

The definitions of “left” and “right” are among the hardest things to understand in Latin American politics.

You are correct. AMLO is an absolute skinflint when it comes to spending on social services. I believe that his opponents initially tried to paint him with that brush because he threw a monkey wrench into their unfettered ability to drain public coffers, then they figured out all they had to do is switch parties and call themselves “Morenistas” to continue raking in the graft

I was in Brazil in 1994 as a 19 year old missionary of the Church of Jesus Christ. You did your shopping at soon as you got your monthly allowance. I also ended up with a substantial coin collection, gathering up discarded specimens from defunct issues as we walked around the dirt roads preaching.

It was disorienting when they brought in the Real, and all of this came to an end. I expect there’s still many worthless coins in the soil waiting for future archaeologists.

In the late 80’s and early 90’s I worked for a firm that did physical foreign exchange, and the South American currencies were a no go zone, many of the countries changing the name of their unit as the old one got hyperinflated too much, Soles got turned into Intis, Cruzeiros got turned into Cruzados and then into Cruzeiros again, and so on. They all pretty much did it.

To hold any inventory of these unfortunate unloved currencies was a fools errand, all it did was go down in value. On the wholesale market there would be huge buy/sell spreads on these hot potatoes

And it wasn’t only Mexico and points south, with the exception of the South African Rand, nobody really wanted much to do with African currencies also susceptible to hyperinflation, along with a few in Asia and even Israel had a bout with it.

But this was when physical banknotes loomed large…

Aside from Venezuela’s nearly 40 year hyperinflation without hiatus, there aren’t really any currencies going that route in our mostly digital now financial world.

I used to be able to purchase brand new bundles of 100 of the latest victim of hyperinflation from a currency dealer in the 90’s for anywhere from $8 to $15, I could have my pick of the aforementioned South American banknotes or something as exotic as Polish Zlotys or what have you.

Currencies were always going out of business, which is why Ecuador and El Salvador adopted the almighty buck as their national currency, so as to get stability.

Surprised to hear that South America is suffering drought. I assume it is a glacial drought, that might be there to stay. But the rainforests, and the Amazon River? What are the statistics for developing countries that manage to create a certain self sufficiency, without the outside influence of empire peddlers – the globalists? Does autarky save countries? I would guess Yes. Because USA. Here we managed to develop one very good infra: agriculture. If people are fed then the rest can be exported. Prices do not go crazy. But global trade has it just backwards: first you produce (whatever it is) for export and then you take the revenue and buy what you need. That’s a plan straight from the profiteers. And for the profiteers. All countries should have a level of self sufficiency that meets the basic demands of their populations. We need to establish those basic needs in a constitution of human rights. Self-sufficiency should never be vulnerable to price inflation; it should exist above it. And in cooperation with other countries. If the profiteers want scarcity to exist (for the sake of profit) let them create it in their own esoteric little markets for cars and art and fashion and various miscellaneous vanities. Economics is not a form of entertainment. It is survival.

nafta billy clinton pedaled that crap in the 1990’s. his brilliant idea of raising cash crops instead of self sufficiency, then buying food on the open market wih the cash from cash crops almost starved asia when free trade blew out the asian economies.

then nafta billy did the same thing to Haita with rice, and he starved untold amounts of people.

his dim wit free trade idea’s for africa doomed millions to starvation, and one country dared to break with his polices.

african country driven into poverty and starvation by faith based free

market economic policies that took away the role of the government and

the disasters mounted, reverses course and collectively uses public

investments in the basics of a farm economy: fertilizer, improved

seed, farmer education, credit and agricultural research, now exports

hundreds of tons of corn doubling their money

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/02/world/africa/02malawi.html?_r=2&pagewanted=1&hp&oref=slogin

before free trade many countries were self sufficient in food, or in very good shape.

the dim wit free traders are going to blow MMT and restore fascist control of interest rates and monetary policy.

i remember when nafta billy deregulated commodities, and a wall street type said the very same day, the era of scarcity is here.

Apparently when the Amazon is a functional rain forest, water evaporating can hold so much “heat of vaporisation” in the form of the vaporised water that the moist air rises so strongly as to pull some ocean-moist air over Southeast Brazil, as far away as that is.

And when Amazon deforestation engineers the Amazon steady rain regime into failure, the relative lack of that air suction engine means less Atlantic air coming over South East Brazil, meaning less rain and more drought over South East Brazil.

If it really works that way, there should be more drought over South East Brazil as the Bolsonarians make a mad dash to burn down as much rain forest as they possibly can, in case Bolsonaro loses power and they are made to stop. Maybe they’ll get enough burned down in the one remaining year that they can turn Amazonia into a permanent dry savanah. Which, if I understand the theory right, would turn South East Brazil into a much more perma-dry place.

California isn’t without natural resources !

Cailf has vast un taped geothermal electricity capabikity the market won’t touch as they are totally for profit “regulated Utility ” meaning they get profit from cost so higher the cost of electricity the greater the profit! They want nothing to do with geothermal! Georgermal electricity is costing 1?2 cent to as much as 3 or 4 cents to produce !

Call me I’ll tell you where to get facts! I don’t really want to be a “reporter”

I would love to see the FF ind. Die! And the people of America prosper instead of the !% prospering!

call 3044661350 or email me

Their profit is a percent of their cost? Then yes, raising their cost would raise their profit. So of course they would seek to make electricity in the costliest way possible.

What if the law were changed so that they got a fixed unchanging set amount of assigned money above cost instead of a percent of cost? Then the lower their cost, the higher the fixed assigned profit amount would be as-a-percentage-of-the-cost. Maybe that would incentivise them to go for lower cost geothermal.