By Guangqing Chi, Professor of Rural Sociology and Demography, Penn State; Davin Holen

Research Assistant Professor, University of Alaska Fairbanks; Heather Randell

Assistant Professor of Rural Sociology and Demography, Penn State; Megan Mucioki

Assistant Research Professor in the Social Science Research Institute, Penn State; Rebecca Napolitano, Assistant Professor of Architectural Engineering, Penn State Originally published at The Conversation.

America’s bridges are in rough shape. Of the nearly 620,000 bridges over roads, rivers and other waterways across the U.S., more than 43,500 of them, about 7%, are considered “structurally deficient.”

In Alaska, bridges face a unique and growing set of problems as the planet warms.

Permafrost, the frozen ground beneath large parts of the state, is thawing with the changing climate, and that’s shifting the soil and everything on it. Bridges are also increasingly crucial for rural residents who can no longer trust the stability of the rivers’ ice in spring and fall.

The infrastructure bill making its way through Congress currently includes US$40 billion in new federal funds for bridgeconstruction, maintenance and repairs – the largest investment in bridges since construction of the interstate highway system started in the 1950s. In that funding is about $225 million to address 140 structurally deficient bridges throughout Alaska.

Given the high cost to build and maintain bridges in rural Alaska, and the increasing risk to their structures as the climate warms, we believe the bill is a good start but hardly sufficient for a growing rural problem.

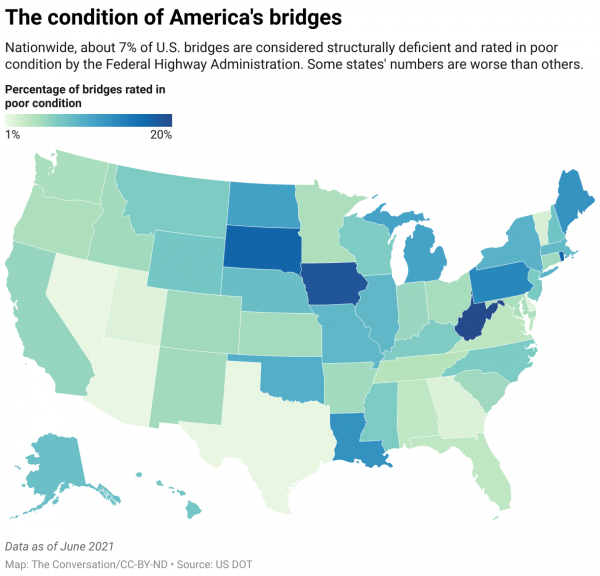

The Condition of America’s Bridges

Nationwide, about 7% of U.S. bridges are considered structurally deficient and rated in poor condition by the Federal Highway Administration. Some states’ numbers are worse than others.

Increasing Need for Bridges as the Planet Warms

Alaska is warming faster than any other U.S. state. As Alaska’s temperature rises, rivers and lakes are freezing later, thawing earlier and forming thinner ice.

When the ice is unstable or unpredictable, people who rely on crossing the river are stuck and the risk of snowmobile fatalitiesrises. Rural residents often use rivers to travel between communities, either as icy roads in winter or waterways in summer, and they often have to cross rivers to hunt, gather traditional foods or reach health care facilities.

Alaska has just over 1,600 bridges that are open to the public – the fourth-lowest total of any state, despite being the largest state by land area. Only about 44% of those bridges are considered to be in good shape.

Building bridges here is an expensive, complex process, and they require long-term maintenance that gets complicated in rural areas. It’s a challenge with two important facets: one is structural, and the other human.

Engineering: The Problem of Permafrost

From an engineering perspective, bridges are vulnerable to the effects of climate change. They are particularly sensitive to seasonal freezing effects, which can quickly change their mechanical properties and structural integrity.

Alaska has some of the harshest conditions for infrastructure, with temperatures ranging from minus 80 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 62 Celsius) to 100 F (37.8 C). Snowfall can reach 81 feet (24.7 meters) per year in some areas, and an ice-rich permafrost underlies 80% of the state.

One of the most important factors affecting the service life of a bridge is corrosion of the reinforcing steel. As permafrost thaws and water becomes liquid, it can accelerate corrosion and cause other types of damage.

A variety of techniques have been used to minimize the effects of cracking, but damage from freezing and thawing still plays a significant role in limiting the lifespan of a bridge. After a bridge is built, it requires regular monitoring to ensure it remains in good condition. That’s difficult in areas that are remote and where harsh weather can be challenging.

Another major engineering challenge for rural areas is human-dependent bridge inspection, which limits how often bridges can be inspected and presents significant safety risks for inspectors. One exciting development in maintenance involves advances in drone technology. Bridge inspections could be done safely by drones and at more reliable intervals, but that too involves investment.

High Costs and Better Planning

Infrastructure construction, especially in rural Alaska, already comes with a hefty price tag.

The cost of delivering steel and concrete to a remote location, sourcing available local materials and bringing in outside specialized labor can significantly increase the cost of a bridge. For example, the 2015 Construction Cost Survey in Alaska found that home construction, based on materials alone, is three times more expensive in Barrow, a remote community in the North Slope of Alaska, than in Anchorage, the state’s largest city.

In rural Alaska, the process of building bridges is complex and can take many years. It depends on cooperation, often among several communities, navigating state processes and support of political leaders. It’s critical to understand from the beginning how a bridge’s construction will affect community well-being and how communities can work together on funding, design, construction and maintenance.

Our team of engineers and social scientists is working on a guide to successful bridge funding, construction and maintenance for remote areas that establishes a community-driven process.

Alaska has no income tax or statewide sales tax and has been facing a fiscal crisis as state oil revenues have fallen. Federal infrastructure investment could help direct funds to rural bridges that might otherwise continue to deteriorate.

I can think of a partial solution to the problem of building bridges in rural Alaska. Build WW2-era Bailey bridges. Before you laugh, consider the advantages of building them-

‘A Bailey bridge has the advantages of requiring no special tools or heavy equipment to assemble. The wood and steel bridge elements were small and light enough to be carried in trucks and lifted into place by hand, without the use of a crane. The bridges were strong enough to carry tanks. Bailey bridges continue to be used extensively in civil engineering construction projects and to provide temporary crossings for pedestrian and vehicle traffic.’

In addition, you do not need specialized factories to build the components for them and I am sure that one can be set up in Alaska. It requires very little training to have a crew to learn how to build one and as the US Army is still building them, they could supply an initial training cadre. You could train up a crew that would go from place to place building them once the materials have been delivered onsite. Hell, I am sure that the Alaska National Guard could be used to bring in the materials using their transport capacity and the mobile quarters/field kitchen for this crew to live in. They may not be pretty but I am sure that if you asked rural places if they would like one built or waiting for Congress to do the right thing by them, then I am sure that they would choose the former-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bailey_bridge

+1000 on the Bailey bridges. They are simple and durable. This Bailey bridge in Italy has been in continuous use since 1945. Every now and then, someone needs to replace worn planks and tighten the bolts.

https://www.youreporter.it/foto_ponte_bailey_fra_quero_e_vas_sul_piave/

En route to the Ladybug & Garfield Grove trails on the southern end of Sequoia NP there was a 1-lane Bailey bridge since the 1950’s that only recently was replaced by a concrete 1-lane bridge.

Too bad sales tax and state income tax are completely off the table as a funding source and their representatives in Washington are against Federal funding.

I guess amphibious cars are the future for Alaska.

Yet Alaska remains financially healthy:

(1) ALASKA remained in first place in our ranking because our analysis includes the state’s “Earning Reserve Account” as assets available to pay bills. This treatment is in line with the state’s audited financial report, which indicates the state had more than $32 billion in “spendable” assets. The state transferred money from the general fund to the permanent fund which led to a $6.5 billion decrease in the state’s money available to pay future bills. Nevertheless, Alaska still had a surplus that breaks down to $55,100 for every state taxpayer. The state had plenty of money to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic yet received federal aid.

https://www.truthinaccounting.org/news/detail/financial-state-of-the-states-2021

Yes, the climate does change. Prior to the Industrial Revolution as well as now.

doesn’t it ever occur to anyone that building of roads and bridges is part of the problem that causes melting permafrost? steel and cement making are responsible for almost a sixth of anthropogenic CO2…

What you say is quite true. However if people are going to live there, they need to be able to connect with at least their immediate neighbours and that means some sort of roads and bridges to cross water and the valleys. No roads, no communities and I am even talking about walking distances here.