By Chiara Burlina, Assistant Professor of Applied Economics, University of Padova, and Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, Princesa de Asturias Chair and Professor of Economic Geography, London School of Economics; Research Fellow, CEPR. Originally published at VoxEU.

Western countries are facing an ‘epidemic of solitude’. Though its impact on mental health has attracted considerable attention, little is known about its economic effects. This column distinguishes between two forms of solitude – loneliness and living alone – and studies their influence on the economic performance of European regions at the local level. Greater shares of people living alone drive economic growth, whereas an increase in loneliness has damaging economic consequences. Though the relationship is complex and non-linear, a region with more lonely people will experience lower aggregate economic growth.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought to the fore the salience of solitude in modern societies (Smith and Lim 2020). Solitude often takes place “when a person’s social relationships are perceived by the person to be less in quantity, and especially in quality, than desired” (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2021). In this case, solitude can be equated with loneliness – a distressing experience that can lead to irritability, depression, and increases in premature deaths (Cacioppo and Cacioppo 2018).

Solitude may also refer to people living alone, without the company of family and friends. Living alone normally lacks the negative connotations associated with loneliness (Kurutz 2012). Increasingly, individuals live alone not because they are forced to but out of choice (Wilkinson 2014). In the so-called ‘second demographic transition’ (Van De Kaa 1987), the archetypal profile of the elderly citizen living alone was replaced by that of an adult professional, often a woman, with high levels of education and stable employment. However, in times like the current Covid pandemic, which are characterised by forced or self-isolation, the life satisfaction of people living alone can decrease (Hamermesh 2020). This may have implications for aggregate economic activity.

Generally, being lonely and living alone describe different states of mind and can represent different attitudes towards life, leading to diverse aggregate economic outcomes. Factors like the greater participation of women in the labour force, increased life expectancy, and urbanisation are pushing more and more people to live alone. The share of individuals living alone has consequently been rising for some time (Sandström and Karlsson 2019). But living alone does not necessarily mean that individuals are lonely. Lonely individuals often feel isolated, indicating an emotional detachment from others and society, whereas many of those living alone lack this emotional detachment and lead vibrant social lives. They frequently compensate for the lack of in-person interaction within the household with a wide network of interpersonal face-to-face and digital relationships outside it.

When they are combined, these two dimensions of solitude may have detrimental implications from a purely economic perspective. First, more people feeling lonely and/or living alone may reduce the number of interpersonal and face-to-face interactions at the heart of the development of new ideas and innovation (Storper and Venables 2004). Second, many people affected by solitude may shy away from engaging in economic activities. Third, different forms of solitude may undermine trust and prevent the formation of bridging social capital, which has been identified as an important factor for regional economic growth (Muringani et al. 2021). Yet living alone is costly, and those living alone require considerable economic resources to finance the costs of properties and rents. This may somewhat counterbalance the potential negative economic effects of the rise in solitude across the developed world.

Loneliness and Alone Living and Economic Growth

We investigate the effects of living alone and being lonely on economic growth across 139 regions of Europe in the period before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (Burlina and Rodriguez-Pose 2021). Our study considers three main measures of solitude: the share of people living alone on the overall population; a sociability index as a proxy for loneliness, covering the degree of interaction within a region measured by the number of in-person meetings for social purposes, regardless of frequency; and the frequency of personal interactions (ranging from daily social meetings to never meeting anyone else for social purposes).

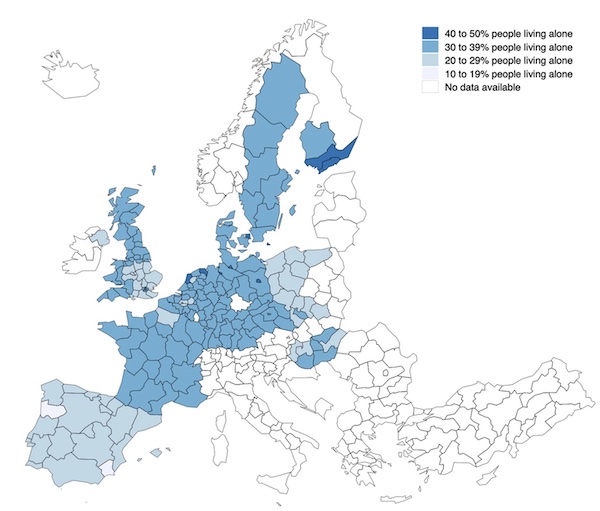

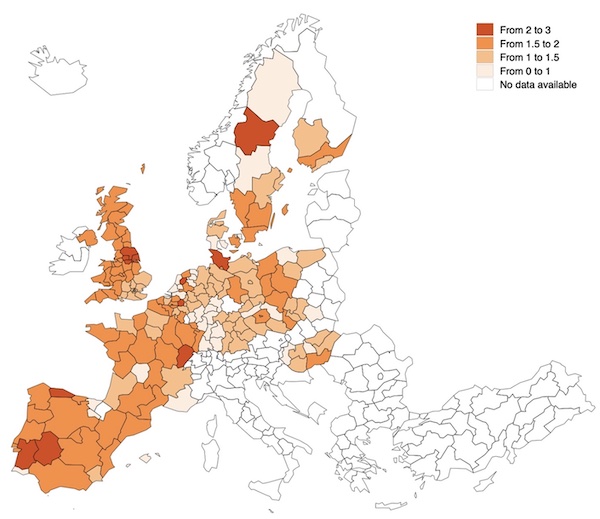

The European geography of these different forms of solitude is extremely variegated. Figure 1 shows the geographical distribution of (a) the share of individuals living alone, and (b) the sociability index. The share of individuals living alone is far higher in Nordic countries and in Central Europe than in Iberia and Eastern Europe. National borders are in clear evidence and there is a marked rural/urban divide.

The geography of sociability/loneliness is more intricate. Southern countries such as Spain and Portugal have a higher degree of sociability. But high levels of sociability are also in evidence in other countries, such as France, the UK, and Sweden. There are strong regional variations within countries – differences in sociability between Schleswig-Holstein and Baden-Württemberg, for example – and no clearly discernible urban/rural, city/town patterns. Many of the regions with a high concentration of people living alone – such as Brussels, most UK regions, Franche-Comté in France, or Schleswig-Holstein in Germany – also have a high sociability index.

Figure 1 Share of people living alone and sociability index

Panel a

Panel b

Sociability Drives Growth, but the Relationship between Loneliness and Growth is More Complex

Though the rise of solitude has potentially pernicious health, mental health, and social consequences, it does not pose the same threat from an economic perspective. Greater shares of people living alone contribute to driving economic growth across European regions. The increasing number of people choosing to live alone – rather than being forced to by external circumstances – can boost economic growth, provided they remain active in the labour force and willing to network and interact with others.

The rise in loneliness, by contrast, has damaging economic consequences on the whole. A society with greater numbers of people feeling lonely has a more limited capacity to generate additional wealth. The connection between loneliness and economic growth, however, depends on factors such as the frequency of meetings between people. Too much interaction, such as the prevalence of daily meetings, can undermine the benefits of in-person exchanges. Societies where a large share of individuals meet on a less than weekly basis are also less likely to grow. The ‘sweet spot’ seems to be large shares of the population meeting with friends, relatives, and co-workers on average on a weekly basis.

COVID-19 is bound to accelerate the rise of different forms of solitude (Hamermesh 2020, Belot et al. 2020), necessitating a greater need for policies that mitigate its negative effects. It is not always clear how governments and administrations should intervene in areas that belong in the sphere of the individual; any form of solitude can be the result of personal choice. However, the fact that the economic consequences of rising solitude can be felt not just at the individual, but also at the aggregate level demands greater policy consideration. Policies such as facilitating choice in the case of living alone are already on the table in some countries. Greater intervention may also be required in order to combat the ‘loneliness epidemic’. In any case, searching for solutions will require addressing the roots of rising solitude to prevent or minimise its negative collective health, well-being, social, and economic consequences.

“ Though the relationship is complex and non-linear, a region with more lonely people will experience lower aggregate economic growth.“

Is there nothing that is not framed in terms of growth? Has there ever been a belief system so unquestioned across such a large swath of the earth, across so many cultures, as that of perpetual growth. We even create equations to convince ourselves perpetual growth in a finite system is possible. Insanity

My immediate reaction to this was the same as yours — an attempt to quantify human interaction soley in terms of economics is pretty sad to see. Putting people’s welfare first seems completely impossible in the current zeitgeist.

Part of the problem of alone/loneliness is the disappearance of

a ‘third place’. People in earlier decades had three places where

they could exist, work, home, and someplace like bowling alleys,

cafes, clubs, public libraries, bookstores, parks, or churches.

Sometime after the turn of the century, people began ‘cocooning’.

All the entertainment they needed was at home, tv, dvds, computer

games, the internet, etc.

Occupants of third places often had the same feelings of warmth, possession, and belonging as they would in their own homes. They feel a piece of themselves is rooted in the space, and gain spiritual regeneration by spending time there. At the very least, the ‘third place’ offered the possibility of either not being alone or being lonely.

Yes! The Great Good Place by Ray Oldenburg. A great book about life that we will live again if what passes for civilization is to survive with an appropriate footprint. In our mid-size city, we are trying but the coronavirus keeps getting in the way. Not that the Neoliberal Project gives a flyin’ flip.

“All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”

– Blaise Pascal

It sounds simplistic but it’s true. “In a room alone” doesn’t mean bereft of stimulation nor bereft of purpose. “To sit quietly” is to concentrate on something. People really ought to do more of it – regardless of its “growth” potential. Crickey.

I lived alone for a few months in 1971 when I migrated to Joberg.

Never since again or again. Being alone was miserable.

This was the remedy

Makes me wonder at what point alienation aggregates and society (thus economies) literally collapses. The stress of growing hardship, situations that never improve but relentlessly become worse, deaf and incompetent governance, etc. I think the modern-day equivalent of walking away from it all, migrating to the next valley, is withdrawing from all the harmful and enervating consequences of social irresponsibility. At some point people don’t have enough energy left to even care. It might be better to understand social (broad scale constructive social relationships and improvements) cohesion factors rather than their absence (social isolation). Studying the absence of something is like proving a negative. Social isolation is when cohesion is not working. For whatever reasons. Many of which are now staring us in the face. And predictably as ever, our dear leaders are completely out of their element. We might as well be El Salvador.

Great point and insight into the subject.

The other day I asked “what would the mission statement be of a group you would like to join? What would you put in, what would you get out? What would earn your commitment?

I think one good reason for the isolation is that the menu of groups to join is thin soup.

And, btw, that might help explain “social media”.

Maybe it’s actually social “tina”. As in “There Is No Alternative”.

Why does one need to join ersatz groups -? Having a life isn’t taught in school, quite the opposite.

At the emotional level, you “need to” if you need to. Otherwise not.

As just one example, if one tends toward the introvert end of the introvert-extrovert scale, then social-groups (.vs. functional) may not have a lot of appeal.

The aspect of group-joining that I’m contemplating here isn’t social groups as much as the purpose-driven groups like guild, labor union, church, or local volunteer fire company. For a lot of good reasons, the rationale for investing oneself in that sort of group has significantly attenuated over the past few decades.

For the social-emotional needs, we have social media. It’s casual, often anonymous, inexpensive, and not really that useful when “times is rough”. It’s like a game of Solitaire with someone that can say unexpected things / play usual cards. Entertainment.

And that’s what motivates me to re-visit, occasionally, the “what group would I actually invest significant effort and time into?” question.

For me, the answer would tend toward “so I could achieve something valuable that I can’t do myself”.

Introverts need that sense of group belonging too, even if they wear its benefits differently.

like you, this is more vital and intersting to me than the level of ‘Economic Engine’ the living arrangement is:

It might be better to understand social (broad scale constructive social relationships and improvements) cohesion factors rather than their absence (social isolation).

and i think would better illuminate the Lonely-ness effect.

as an aside—Salvadorians I knew here(usa) had extensive and operating social networks which enabled their migration/employment and housing from toe hold to beach head to hinterland. Similar, in fact to similar social relations that enabled the Eastern European(my Mother’s lineage) immigration at the turn of the 20th century. I have a grudging admiration of sorts that i have not tried to de-strand for awhile.

This is not to diminish your point of the chaos that is El Salvadore today.

Increasingly, Westerners whose parents could afford small homes cannot even afford one of the increasingly scarce studio apartments.

They are crammed into apartments with multiple roommates, or living by obligation with family members.

Both the mental health and Covid health implications are obvious.

Certainly, those people would envy those who are living alone.

Whatever the validity of the data or interpretation, the there is a class bias in the choice of the researchers’ topic.

I’d rather be alone than live with lousy roommates. Company is just like anything else, good ones absolutely, bad ones, absolutely not.

LOL … #True

“I knew my introversion would come in handy one day.” (via Introvert, Dear – An Award-Winning Community For Introverts)

Us Brits would like to live alone more but housing in SE England is just so expensive :(