Yves here. On the one hand, these authors no doubt performed their supply chain analysis and largely wrote their paper before the Ukraine war and its sanctions onslaught. On the other, it illustrates how experts and participants have blind spots about the potential for paradigm shifts, in large measure because they have strong incentives to preserve the existing status quo, no matter how creaky it has gotten. In ECONNED, we called this process paradigm breakdown:

Paradigm breakdown, meaning key elements of the current system are no longer viable, but that is a possibility that no one is prepared to face, since the old system seemed to work well for a protracted period. Thus the authorities reflexively put duct tape on the machinery rather than hazard a teardown.

Covid disruptions, bird flu, and pre-war fertilizer shortages were already creating serious food price increases in the US. But the sanctions on Russia are creating an entirely different and more durable changes, not mere disruptions or “shocks”, given the near-certainty that the US will not roll them back, even if Zelensky agrees to a peace treaty with Russia. The West is going to suffer lasting shortages of key materials, such as palladium, nickel, aluminum, steel, copper and platinum. Ukraine is a major supplier of neon, necessary to chip-making. Russia provides several important inputs to fertilizer, so food will become more scarce and costly. And that’s before we get to the impact of wheat shortages (and the West being a less-preferred customer) and higher energy prices (which emergency reserve releases can moderate for only a matter of months).

Papers like this remind me of Keynes’ observation about bankers:

A ‘sound’ banker, alas! is not one who foresees danger and avoids it, but one who, when he is ruined, is ruined in a conventional and orthodox way along with his fellows, so that no one can really blame him.

Making Russia more of an autarky, which Russia can survive, is going to force the rest of the world in that direction. Very few seem willing to get in front of that development…save the serious gloom and doom types, aka preppers, who are generally seen as extremists, and may well be….unless they are eventually proven right.

By Richard Baldwin, Professor of International Economics at The Graduate Institute, Geneva; Founder & Editor-in-Chief of VoxEU.org; ex President of CEPR and Rebecca Freeman, Trade Associate, Centre for Economic Performance (LSE). Originally published at VoxEU

Supply disruptions caused by systemic shocks such as Brexit, Covid, and Russia-Ukraine tensions have catapulted the issue of risk in global supply chains to the top of policy agendas. In some sectors, however, there is a wedge between private and social risk appetite, or increased risks due to lack of supply chain visibility. This column discusses the types of risks to and from supply chains, and how supply chains have recovered from past shocks. It then proposes a risk-reward framework for thinking about when policy interventions are necessary.

The past couple of years have been rife with upheaval – whether we are speaking of people’s day-to-day lives, disruptions to business-as-usual, or international trade flows. The Brexit shock in Britain sparked initial concerns about the impact on global supply chains (GSCs). This was followed by the much larger and wider shock from the Covid-19 pandemic. The current political situation between Russia and Ukraine, including many countries’ sanctions and bans on the import of Russian products, is likely to perpetuate the spectre of broad and long-lasting shocks to multiple economies.

What should be done about this? Noting many challenges to global supply chain resilience, Seric et al. (2021) examine how firms involved in global supply chains can help mitigate the effects of supply disruptions. Further, recent research on global supply chain risks has shown that inventory management helps firms mitigate global supply chain shocks (Lafrogne-Joussier et al. 2022).

This column, based on Baldwin and Freeman (2021), (1) examines how the literature has thought about sources of shocks, risk and resilience in the context of global supply chains, including whether a shift in the thinking around risk is called for; and (2) offers a brief discussion on how to apply our proposed framework to policy discussions and future work on the topic.

Sources of Shocks

GSCs are composed of firms and firms face risks. Some of these risks are exogenous supply and demand shocks, other shocks emanate from other firms or transportation disruptions.

- Supply shocks include ‘classic’ disruptions such as natural disasters, labour union strikes, suppliers going bankrupt, industrial accidents, and so on (Miroudot 2020), as well as disruptions from broader sources like trade and industrial policy changes, and political instability. They can be concentrated (e.g. the 2011 Japan earthquake) or broad (e.g. the Covid-19 pandemic).

- Transportation is part of the services sector, and thus potentially subject to different shocks than goods.

- Demand shocks confront firms with risks stemming from damage to product and company reputation, customer bankruptcy, entry of new competitors, policies restricting market access, macroeconomic crises, and exchange rate volatility.

Another important dimension of risk concerns the idiosyncratic-versus-systematic nature of shocks. Most firms involved in global supply chains are aware of idiosyncratic shocks – those which affect single sectors or factories in single nations. These are frequent. Systemic shocks are a different matter.

From the 1990s until recently, shocks rarely involved many sectors/nations simultaneously. This is really what was new about the Covid-19 shocks to global supply chains, which were pervasive, persistent, and affected multiple sectors at once. And while many firms do have contingency strategies in place, few firms engaged in global supply chains – not even the most sophisticated multinationals – had prepared for systemic shocks. This is a real change.

The Business Continuity Institute Supply Chain Resilience Report 2021, which surveyed 173 firms in 62 countries, found that over a quarter of firms experienced ten or more disruptions in 2020, while the figure was under 5% in 2019. Firms cited Covid-19 for most of the rise in disruptions, although Europe-based firms also pointed to Brexit as an important source of shocks.

There are two other likely sources of systemic shocks: climate change and geostrategic tensions. In short, systemic shocks may become the norm and thus require changes to business models worldwide.

Even though the pandemic waxed and waned regionally, it has been global in nature. Because of this, the impact was felt in almost all goods producing sectors. We cannot know how frequently future pandemics or disruptive global events will occur, but it is likely that Covid-19 will continue to be disruptive for many months or years.

Economic Analysis of GSC Risks, Resilience, and Robustness

The literature has focused on three aspects of global supply chain risks:

- The propagation of micro into macro shocks

- Whether global supply chains amplify the trade impact of macro shocks

- The costs and effects of delinking/decoupling from GSCs (e.g. through reshoring).

Our paper reviews these three literatures, but for the sake of space, we concentrate on policy issues here. Before doing so, we touch upon the critical distinction between resilience (ability to bounce back quickly after a shock) and robustness (ability to continue production during the shock). To ensure resilience, much of the focus is on designing the supply chain with an eye to the riskiness of locations overall. In contrast, robustness strategies focus more on ensuring redundancy of external suppliers or having multiple production sites for internally produced inputs (Martins de Sa et al. 2019, Brandon-Jones et al. 2014).

Do We Need New GSC Policies?

A touchstone principle of the social market economy is that government intervention is merited if there are gaps between the private and public evaluations of costs, benefits, and/or risks. When it comes to GSC policy, we argue that policy may improve market outcomes when there is a wedge between private and social evaluations of risk.

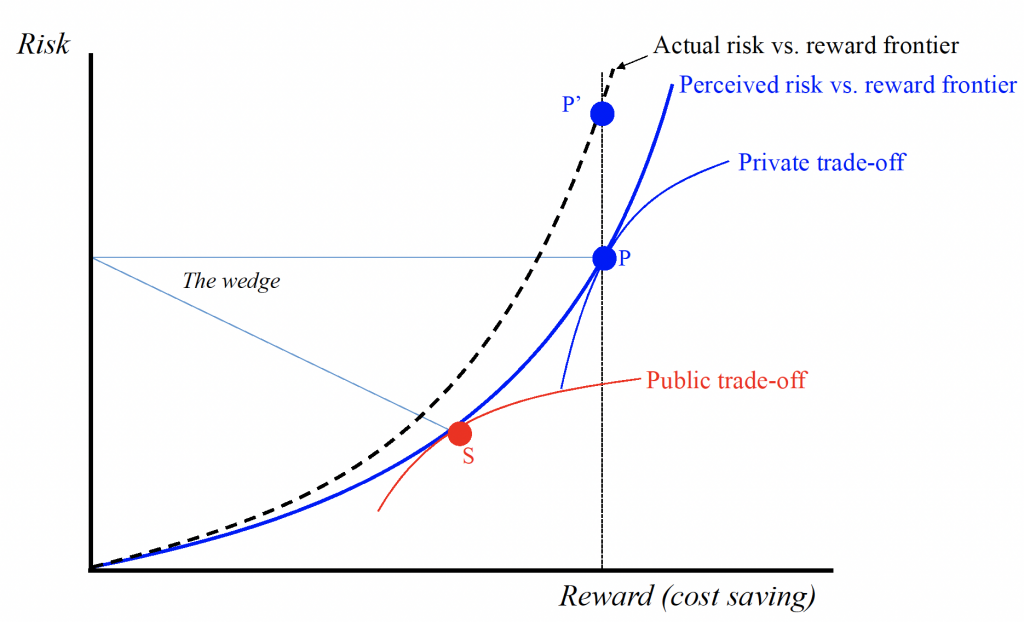

We illustrate this for global supply chains with a ‘wedge diagram’ (Figure 1). The diagram, styled on classic optimal-portfolio analysis, has risk and reward on the y-axis and the x-axis, respectively. Firms like cost-savings and dislike risk (as shown by the indifference curves), but their choices are constrained by the fundamental risk-reward frontier shown. The frontiers take their shape since putting all production in the cheapest location increases risk by decreasing geo-diversification.

Where does the wedge come from? Public versus private risk appetite. In the GSC world, divergences in public-private risk preferences can arise from a range of mechanisms whereby individual firms do not internalise the full risk of their actions. Private firms optimally choose point P given their preferences. In some sectors, many governments have preferences that give greater weight to risk reduction, so the public trade-off leads to a lower-risk optimum, creating a wedge between public and private risk evaluations. This divergence is clear in sectors such as banking where, in the past, government provided guarantees when the risk went wrong, and in food production where individual producers underinvest in anti-famine actions.

Misperception of the location of the frontier. Another market failure can arise due to information asymmetries. Modern global supply chains are massively complex and even the most sophisticated firms can be unaware of the location of their third-tier suppliers and beyond (Lund et al. 2020). As a result, private firms may face more risk than they know. This situation is depicted as the actual risk-reward trade-off taking place above the perceived trade-off, which would also result in a wedge. When this is the case, private firms are at point P’ when they think they are at P.

Figure 1 The public-private wedge analysis of GSC risks

Source: Baldwin and Freeman (2021).

Policies to Mitigate Risk

Risk mitigating policies – such as those in banking and agriculture – are clearly warranted when such a public-private wedge exists. Banking is the classic sector with a wedge, but food has one as well given that it is almost universally considered too critical to national wellbeing to be left to the market. Most nations have policies that promote domestic production create buffer stocks to smooth demand and supply mismatches, or both. These typically involve large scale outlays such the US Farm Bill and the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy.

It seems likely that critical sectors, including medical supplies and semiconductors, will be viewed more like agriculture and banking going forward than they have been, since the perception is that they are marked by a public-private wedge. Policies that tackle the wedge can be usefully classified into tax/subsidy measures, regulatory measures, and direct governmental control. And, as firms are more likely to shift production structures when they perceive a permanent policy shift (Antràs 2020), we speculate that these sectors are most likely to restructure and reorganise their GSCs. On the policy side, there have been clear moves to evaluate critical sectors. For example, the Biden administration has established a Supply Chain Disruptions Task Force to address the challenges arising from a pandemic-affected economic recovery (White House 2022).

A Target-Rich Research Environment

We end our paper, and this column, with a call for research. On the trade theory side, almost no analyses had delved into the role of risk in GSCs when we started circulating our paper in 2021. For example, in the received wisdom literature (Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg 2008), the basic trade-off turns on separation costs versus cost-saving gains in a model without risk. As the discussion of the International Business literature in our paper makes clear, the risk-GSC nexus serves up a rich menu of un-modelled, yet important phenomena. Of course, risk considerations are not entirely new (Costinot et al. 2013), but the theory has largely assumed away risk for convenience, and this has been echoed in the empirics.

On the empirical side, the possibilities are even greater. Nothing helps econometricians more than truly exogenous shocks. The years 2020 and 2021 were bursting with exogeneity. Because of this, coupled with the availability of massive, high-frequency, online data, and headline-grabbing importance, we conjecture that there is a great deal of impactful empirical research to be done on risk and the shape and nature of GSCs. Overall, we see exciting times ahead for GSC researchers. Things have, as they say, changed so much that not even the future is what it used to be. It is riskier than we thought!

See original post for references

You are neglecting the agency aspects of supply chain vulnerability. Managers are often well aware of real value destruction caused by increasing short term profit by neglecting supply chain risk. But the bonuses earned from increasing short term profit via just-in-time, off-shoring, and single-sourced supply of a crucial (e.g., semiconductor) component will never be clawed back. Military procurement, by the way, incurs substantial extra cost by regulation to ensure multiple suppliers; this is a feature, not a bug.

Supposedly the one reason AMD is making x86 CPUs these days is that IBM forced Intel to license the ISA to third parties. This to ensure that IBM had a second source for CPUs in case Intel could not meet demand. Where oh where is that kind of management these days?

Japan?

https://qwant.com/?q=edwards+deming+peter+drucker+japan

It is amazing how observant Deming, Drucker (and Juran) to understood what the Japanese should NOT to import from the United States. Deming saw the best efforts in the US WW2 effort with its successful application of statistics and organizational practices. After the war, in short order these guys had nothing to do in the United States and a very perceptive audience in Japan. Japan is constrained geographically, but proximity of suppliers would have been part of their prescription, regardless.

They lived long enough to see a supposed revival in the US of quality-focused management, which quickly degenerated into a “business ” of supplier audits, certifications and credentials of any sort imaginable necessary for to facilitate pay-to-play.

Recall Jack Welch’s Six Sigma cultists with green, red, brown or black belt certifications? This nonsense happened while Neutron Jack financialized an American industrial crown jewel, trashing it with his pedal to the metal for shareholder value, heading for the cliff. Now the Six Sigma belts would be rainbow flagged and knowing algebra or statistics not required.

Amen brother.

First of all that paradigm breakdown sounds similar to what i have seen elsewhere labeled as hypernormalization.

As for preppers. the problem is that most preppers take a “mad max” kind of attitude to it. Meaning that the focus more on bullets and tin cans (and maybe some gold, or perhaps crypto these days) than seed plants and general self sufficiency. If they did the latter they would be (subsistence) farmers, not preppers.

People seem to be coming out of the woodwork to join the ranks of the “gloom and doom preppers” who are long used to ridicule from “straight” folks. Allow me to suggest that most preppers are not the “Mad Max” variety, and lots of them have pretty good, practical ideas and display sound thinking based on their belief. There are all kinds. How many “doom and gloomers” have come to their present state of mind by realizing that *none* of the problems leading to collapse are being solved. Global warming, species depletion, pollution, wealth inequality, industrial farming, hegemony wars etc. and just plain greed are problems that will be solved by total collapse of the system we live in and not by anything we are (not) doing in the meantime. It won’t be pretty, and maybe nothing can be done to survive. As for views that decimation of the human population is seen as desirable by the ruling class — this has yet to be proved untrue. Hubris is thinking you are above and beyond the situation.

I often half joke that the smartest thing to do is move to a small Mormon community because they still have this outlook. They and evangelical fundamentalists (of the pre 1980s sort) seem to dominate practical prepping on the internet, since they have traditions of living in isolated community.

They also have an interesting relationship to optimism and hardship that is the rest of us would do well to learn

Yes, when survival means growing your own food, being part of a community is essential. (I wonder how long it will take to deplete the deer population in America.)

“I wonder how long it will take to deplete the deer population in America.”

Haha, juno mas, not soon enough for me! In our ‘neck of the woods’ in south-western New York state, the deer will eat everything you plant …. trees, fruit bushes, vegetables, rye, buckwheat. Correction, they will not eat: lilacs, garlic, onion, leeks, bee balm, sage, thyme …..

And, supplies of wire fencing are disappearing.

How does free trade actually work?

Why is it so much cheaper to get things made elsewhere?

The early neoclassical economists took the rentiers out of economics.

Hiding rentier activity in the economy does have some surprising consequences.

The interests of the rentiers and capitalists are opposed with free trade.

This nearly split the Tory Party in the 19th century over the Repeal of the Corn Laws.

The rentiers gains push up the cost of living.

The landowners wanted to get a high price for their crops, so they could make more money.

The capitalists want a low cost of living as they have to pay that in wages.

The capitalists wanted cheap bread, as that was the staple food of the working class, and they would be paying for it through wages.

Of course, that’s why it’s so expensive to get anything done in the West.

It’s our high cost of living.

Disposable income = wages – (taxes + the cost of living)

Employees get their money from wages and the employers pay the cost of living through wages, reducing profit.

High housing costs have to be paid in wages, reducing profit.

The playing field was tilted against the West with free trade due to our high cost of living

The early neoclassical economists had removed the rentiers from economics so we didn’t realise.

That’s why it’s so much cheaper to get things made elsewhere.

I spent quite a few years attempting to develop systems that would perform decently better in the before times but have great resiliency in the new ordinary. Everyone agreed with this but there was not the institutional energy to switch within the TBTF companies that set all the rules.

I had thought, “well let’s see who comes crawling back when disruption hit” but no one has. The reason? They’ve just hiked their prices to keep the same margins on a percentage basis and so input costs rising has led to even greater profits!

All risk has been shunted to workers, primary and intermediary producers who have had their margins squeezed to zero for decades, and are now going under in droves. Government support programs keep some on life support but are just a wealth transfer in another name to TBTF players.

This paper talks about market balance but there is no market, just a web of monopolies and monopsonies with cartel dynamics. It is a new aristocracy, with even less conscience.

This state of affairs will last until it can’t. Forget collapse of companies or even industry, it will happen on a country by country level, of course starting with the poorest as always. I hope Hudson is right that this will finally end the Washington Consensus and give hope in something new.

actually the authors call this a market failure. it was not. what it is is a failure of governance. dupont warned nafta billy clinton that the supply chains in america would fail and move off shore with all of our industries, jobs wealth and technology. nafta billy clinton ignored all that, and from 1993 onwards, the market governed itself.

free trade has never worked. remember, most wealth in europe was robbed at gunpoint from those who did not have the power to protect themselves, its still going on today.

the corn laws were repealed because it was cheaper to exploit the colonies, than to pay market prices at home.

most of what many people know about free trade is complete economic rubbish. the myths, its helps the poor, never has, never will, it exploits the poor and makes their lives even more miserable.

it gives the poor a job, in most cases they were already employed, then free trade destroyed their jobs forcing them into slave/sweatshop labor.

it gives the poor cheaper prices, nope, it cost a nation a lot of money to stock their shelves with foreign made products, we can see the folly of that today.

free trade has so many liabilities, contradictions, and absurdities, just to many to list.

but getting rid of the corn laws, meant using great britons colonies to raise cash crops, under cutting local production in great briton, and it ended up starving a lot of poor in india and other european colonies.

there never was a concern about competing, its all about a few parasites controlling markets and whole countries for massive gains for a few, to the detriment to the many.

https://yourstory.com/2014/08/bengal-famine-genocide/amp

Nice to see that agriculture is considered nearly as essential as banking

You wouldn’t know it from the PMC whingeing I have to hear in Canada against our supply management system to protect the domestic dairy industry.

Yossi Sheffi professor at MIT covering Logistics suggest corporate culture plays a large part in the resilience of supply chains and firms need to build a culture of flexibility. He suggests distributed power and continuous communication are required. Managers communication needs to be high quality and show deep knowledge otherwise it gets tuned out. Marketing needs to be focused on quality and service rather than price. In my view this suggests UK and US business culture may not be equipped to tackle this.

https://covid-19.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/qyyrs8g4/release/1

Semiconductors are a tricky industry to replicate in every nation in way that food and banking are not. Semiconductor industry relies on very rare inputs and has huge economies of scale.

I suspect it can only be duplicated for the lower performance, large process size segment(>100nm) segment of the market.

Patrick — that is so true. And beyond that is software as I discuss at RobertC March 17, 2022 at 4:16 pm

Richard Baldwin summarizes:

It’s hard for me to believe in the age of artificial intelligence applications and high performance computing there do not exist formal models of national, if not global, economies and their associated supply chains.

At minimum sufficient to address systemic shocks in national food security supply chains.

Food security being a new addition to China’s national security strategy last November.

A simple AI economic modelling application may include the Input–output model (and its extension Consistency Analysis). There are assuredly more sophisticated applications in this and other fields of national security interest.

I’ll note there is strong Russian (Soviet), Chinese, UK and Indian presence in economic modelling (eg, Elsevier Economic Modelling journal) and its special issues, eg Elsevier Special Issue.

My conclusion: problem addressed with adequate solutions deployed by those governments proactively tackling rapid climate change (eg, China).

This post contains some interesting statements:

“On the trade theory side, almost no analyses had delved into the role of risk in GSCs when we started circulating our paper in 2021.”

“Of course, risk considerations are not entirely new (Costinot et al. 2013), but the theory has largely assumed away risk for convenience, and this has been echoed in the empirics.”

“Overall, we see exciting times ahead for GSC researchers.”

I am so glad GSC researchers have cause for excitement./s

As I recall, Japan pioneered just-in-time systems of inventory, but with some significant differences from how just-in-time is practiced in today’s [GSCs] — Global Supply Chains. I thought the Japanese version of just-in-time was a system for coordinating the activities of nearby suppliers, a little like Henry Ford’s Rouge Factory, but with a different ownership pattern. It took American ingenuity to take the idea, strip out all redundancies, and spread supply networks across the oceans. How remarkable that GSC researchers assumed away risk for convenience in their ‘analyses’. I wonder whether they also find it convenient to assume away the delays and flawed coordination geographically spread long distance suppliers can introduce. Of course they would ignore the ineffably important ties between persons — ties probably nonexistent between persons operating distant entities, with different languages and cultures. I also wonder just how different in action GSCs are from vertical monopolies, after giving due consideration to the contractual and economic ties binding GSCs with the endpoints where the aggregation and assembly of remotely produced inputs results in an end-good. I suppose this question deserves little regard considering how little the u.s. regulates monopoly and monopsony.

Long geographically spread supply chains depend on fossil fuels, primarily diesel, to move goods. The increasing strains and costs resulting from fossil fuel depletion have long been an obvious and very major risk to GSCs. The multiple single supplier sources in ‘optimized’ supply chain have been a known problem for decades. The information in this post suggests to me that Economists and GSC researchers are less than useless.

Exactly. And more to the point, JIT is a process that was developed to support a deeper philosophy of flow and Kaizen. When it doesn’t support those aims it is relaxed or abandoned.

Toyota is suffering the least from production issues because as soon as Covid hit they built up inventory in parts they predicted would be in short supply. Also they have decades long relationships with loyal suppliers that give them preference. Loyalty that exists in part due to sustained ordering regardless of economic conditions. In 2008 they gave direct financial support to suppliers even when their inventory was full and they didn’t need delivery.

In an attempt to quantify and optimize everything, the Western model throws out common sense and flexibility in the face of change. I’m not sure how to address this because it seems to reflect a deep cultural mindset, as well as imperialistic entitlement

What takes me hours of explanation and years of resistance in western decision makers finds full agreement in minutes with most Asian and indigenous ones.

mikkel — looks like you’re working at the coal face. The Western model has succumbed to financial engineering. Best wishes working with more enlightened economies. Certainly Japan and South Korea. What about Vietnam, Bangladesh and India?

yup. JIT requires a very stable supplier network with long term relationships and a real commitment to longevity. It also requires that the suppliers make enough profit to stay in business and invest. US and EU OEMs, automobile is probably the worst, want all of the benefits of JIT and also want to squeeze the suppliers, You can one or the other but not both.

Toyota is no more immune than others from supply chain shocks, they did better upfront because (ironically) they held more inventory of certain components, but once those were drawn down they’re stuck without chips.

Shutdowns at Renesas following the recent earthquake didn’t help matters.

On “Supply disruptions caused by systemic shocks such as Brexit, Covid, and Russia-Ukraine tensions”.

Is that true? Or are the shocks about normal? The system may have changed so that typical shocks cause much more damage. This is the “a low-riding boat will be swamped by normal waves” problem.

And the First World may not be the issue. Population growth and rising expectations may have created a lot of low-riding boats out there.

Interesting discussion.

I think it was mikkel above who said,

“They’ve just hiked their prices to keep the same margins on a percentage basis and so input costs rising has led to even greater profits!”

This can work briefly, however, with many wages stagnant, and most fixed costs for consumers increasing, there is a limit to what the market will bear before we see demand destruction.

I suspect sooner than later.

already happening in automotive. Profits are soaring as volumes are falling.

Profits are soaring in automotive because of the normal response to supply restrictions, such as happened for Japanese firms with the Reagan “Voluntary” Export Restrictions in 1981. Japanese car companies were limited to 1.68 mil units, so they dropped entry-level trim packages and shifted more output to larger, more profitable vehicles.

Ditto today. You can’t find an entry-level vehicle (and, due to other covid side-effects, such as rental car companies having no cars to sell into the used car market) it’s even worse for used cars. There is however a very recent drop in the “suburban cowboy” full-sized, gas-guzzling pickup market, a in the largest of the luxury SUVs. But not otherwise at the high end.

I’ve followed automotive supply chains since the early 1980s, interviewing companies in Japan (in Japanese). Since then a major change in the industry has been the growth of global vehicles and global suppliers. That began with Toyota and Honda and Nissan localizing production of exported models in the US/Canada and the EU, and came after 2000 at GM and Ford whose international operations were autonomous coming out of the 1920s. VW had global models early on, while BMW and Audi for example concentrated global production of a family of models in a single plant (BMW South Caroline exports 60% or more of output as the sole global source of most of the X-series models). A separate change was the greater role assumed by suppliers in supplying new technologies and materials, increasing fuel efficiency and trimming weight and enhancing safety while meeting new consumer preferences all at the same time far exceeded the engineering resources of any firm, or small group of firms.

The result is the global supplier, that has factories in Asia, ASEAN, South America, Europe and North America to supply global cars on a local basis. That provided risk mitigation to “normal” disruptions including localized problems with ocean transport. No one however, including the chip fabs, had foreseen a simultaneous expansion in all markets, from computers and modems for remote work, a very rapid expansion of data centers, crypto mining, and home renovations that included white goods loaded with basic microprocessors. (I’ve taken part in roundtables with industry participants.) Nor is there a ready policy response, given the multi-year lead times to build a new fab, and the equally limited capacity of the suppliers of the equipment those fabs need. Dumbing down cars is not an option, given safety and other regulatory mandates, and the clear risk of consumer pushback against whoever is first to de-content their vehicles.

But all of this is more a story of unexpected demand producing shortages, rather than disruptions to supply. Car companies and their suppliers have done an amazing job at keeping production going throughout the pandemic, despite many, many, many “micro” disruptions as individual parts from specific supplier plants became unavailable. Even in the face of wire harness production in Ukraine, production bounced back.

No individual company, no individual industry, however, can fight the sort of macro trends we are seeing. Steel production is widely dispersed, but in normal times there isn’t excess capacity that can be turned on with the flip of a switch. Ditto fertilizer, wheat and so on. But when markets are balanced, a 10% drop in what’s available for export into international markets has a big impact.

Autarky doesn’t help. The ag econ literature has long noted the deleterious impact of segregated markets, as balkanization concentrates shocks locally, including bumper harvests that couldn’t be exported and so impoverished small farmers. For economists, there’s a good 1981 book by Newberry and Stiglitz. To take an example linked to the current war, there are no short-term measures for Egypt and wheat, which for decades has kept bread prices low to pacify urban voters (if only voters in the form of street protests). That has savaged agriculture, amplifying shocks rather than partially insuring Egyptian food markets.

To conclude my rambling, I read a variety of “economic security” literature 25 years ago, to provide a counter the military security types who dominated an international security conference series. I’ve read some of Baldwin’s work, and will scan this to update myself.