Yves here. I’m old enough to have heard of the regulatory fights over DDT in real time, although not old enough to have grasped the details. But in 1963, CBS broadcast a documentary on Silent Spring which even I recall as having galvanized discussion. Plus recognition of the controversy by one of the three networks was tantamount to an authoritative endorsement of Rachel Carson’s concerns.

By Andru Okun, a writer living in New Orleans. Originally published at Undark

In 1945, Rachel Carson, then a marine biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, developed an interest in DDT, a powerful pesticide used to eliminate insects that destroy crops and carry disease. A decade and a half later, “Silent Spring” was released, a book in which she argued that synthetic chemicals like DDT were also killing birds and fish, entering into the food chain, and contaminating the natural world. Her work, both celebrated and scorned, gave rise to a budding environmental movement and forever altered public perception of DDT.

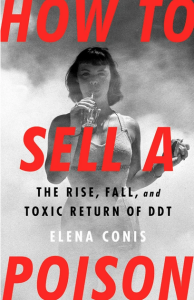

In “How to Sell a Poison: The Rise, Fall, and Toxic Return of DDT,”medical historian Elena Conis provides an updated account of the infamous pesticide. She foregrounds lesser-known figures embroiled in the chemical’s history, telling of the small farmers, medical professionals, and nature enthusiasts who raised concerns about DDT long before it became a catalyst for environmental activism in the 1960s.

Like many stories of American innovation in the second half of the 20th century, DDT’s ascent can be traced to World War II, when it was successfully used to combat malaria-infected mosquitoes in the South Pacific. In peacetime, the production and application of DDT continued. Plywood and wallpaper were coated with DDT in suburban homes. Farmers applied it to cows and crops. Trucks drove around cities spraying it to ward off insects. Conis points out that the chemical was of such little concern at the time that children would play in its mist. “In just a few short years, the pesticide — a relatively simple compound of carbon, hydrogen, and chlorine, used with abandon — had come to symbolize our postwar nation’s capacity to vanquish age-old scourges with modern science and technology,” she writes.

BOOK REVIEW — “How to Sell a Poison: The Rise, Fall, and Toxic Return of DDT,” by Elena Conis (Bold Type Books, 400 pages).

But DDT’s status as a miracle chemical wouldn’t last. When it became a part of everyday American life, there was still little understanding of how it worked. (In fact, the chemist who originally convinced the U.S. government to deploy the pesticide did so by eating a chunk of it in front of the surgeon general.) Later, scientists would discover DDT was a neurotoxin that accumulated in body fat. By then, the chemical could be found in the bloodstream of nearly every American. When Marjorie Spock, an environmental activist and gardener in Long Island, New York, sued the government in 1957 over its spraying of DDT, the defense admitted the pesticide was pervasive while claiming there was no evidence this resulted in any harm to people. And while DDT indiscriminately wiped out wildlife rather than just troublesome insects, the defense claimed these populations bounced back. Those opposed to the use of the DDT, they argued, were simply opponents of scientific progress.

Conis describes how a decade before this courtroom battle, a mysterious disease spread around the country, causing lesions in the skin of grazing cattle and impairing their muscular coordination. People living far from agricultural sectors fell ill, too. Although the disease was thought to have originated in Texas, Morton Biskind, a Manhattan-based physician, began to notice an uptick in patients with unusual symptoms. Further research led him to the determination that his patients’ ailments could all be linked to the chemical. He went on to write a report in 1949 connecting the strange nationwide illness to the widespread use of DDT, writing, “To anyone with even a rudimentary knowledge of toxicology, it exceeds all limits of credibility that a compound lethal for insects, fish, birds, chickens, rats, cattle, and monkey would be nontoxic for human beings.”

Biskind’s revelations pointed to a serious problem: People were consuming the chemical in their food. Even before it became a commonly used insecticide, FDA scientists knew that cows treated with DDT would produce milk and meat laced with the chemical. Still, it was used liberally within agriculture, as were hundreds of other new chemical insecticides made available following the war.

Conis carefully details how public concern over the safety of synthetic chemicals developed in the early 1950s, during which a government task force began to look into the toxicity of the nation’s food supply.

Meanwhile, chemical corporations banded together to create a public relations campaign affirming the necessity and safety of pesticides like DDT. By the middle of the decade, hundreds of millions of pounds of synthetic pesticides were annually produced, sprayed on vast tracts of American farmland. “The U.S. was also applying pesticides abroad, too,” Conis writes, “its DDT the cornerstone of the World Health Organization’s malaria-eradication campaign. Pesticides had never been produced or used on such a scale.”

Social inequality and environmental pollution are often intertwined, a fact Conis draws attention to throughout her book. She recounts how California farm laborers were made sick by the uncontrolled use of pesticides and how the fish in a creek that ran near a predominantly Black Alabama town were contaminated. She also writes about the scary tendency for DDT to impact women and their children, as exposure to the pesticide can occur through breastfeeding as well as in-utero.

Big tobacco becomes a major piece of the story halfway through the book. In 1964, a landmark surgeon general report determined that smoking significantly increased a person’s risk of lung cancer and death. Tobacco’s relationship with DDT stretched back to the 1940s when the chemical was sprayed on fields and in warehouses where tobacco was stored. It was in both cigarettes and their smoke. Thus, the tobacco industry came up with a plan: Blame cancer on the pesticide and then commit to discontinuing its use.

Decades later, in the 1990s, the industry’s stance on the pesticide reversed, spurring the resurgence of DDT. The latter portion of Conis’s narrative tracks how free-market defenders funded by anti-regulatory chemical and tobacco companies used the demonization of DDT to divide environmental scientists and public health experts over the use of pesticides. As the spread of malaria increased throughout the globe, corporate money was funneled into a campaign that denounced the ban of DDT and blamed millions of malaria-induced deaths on overzealous environmentalists.

Conis explains how this campaign served to divert attention away from tobacco’s harm by focusing on a larger threat while also throwing into question global health strategy led by Western nations. Media manipulation, denial, and distraction were crucial to the strategy, the primary goal being the protection of industry. Conis posits that this campaign — what she refers to as “corporate doubt mongering” — helped lay the groundwork for the amplification of scientific uncertainty seen today regarding issues like climate change and vaccines.

The Environmental Protection Agency banned DDT for most uses in 1972. Once acclaimed for its efficacy and low cost, the chemical’s legacy is marked by its heavy toll. While it has been difficult for scientists to conclusively link the chemical to adverse health outcomes for people, researchers have labeled the pesticide a probable carcinogen and highlighted its connection to a variety of cancers. The chemical has also proven to be astoundingly persistent, appearing as far afield as Antarctica, where the pesticide has never been sprayed.

Conis is a sharp writer, albeit more of a historian than a political analyst. While “How to Sell a Poison” includes exhaustive research and vivid storytelling, Conis’s personal take is mostly limited to the book’s beginning and end. Interludes between its three acts would have allowed her to better connect her history to current events, delving further into some of the book’s larger themes while also providing a brief pause in what is an undeniably rigorous history. Still, the overarching message is easily understood: “Seventy-five years after scientists first warned of its hazards, 60 years after Rachel Carson wrote ‘Silent Spring,’ and 50 years after it was banned, DDT is still here.”

A current version of “Silent Spring”:

https://www.chelseagreen.com/product/toxic-legacy/

Now I know where the BS about “DDT being so safe you could eat it by spoonful” comes. Thanks.

Seriously though, I don’t know anymore who is more dangerous, scientists or the corps that hire them.

Scientists that are cock sure about their findings being correct.

Because to them it is not about money or fame, it is about improving the human condition.

And as the saying goes, the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

The organic agronomy scientists who research / researched how to grow food without DDT were/ are also scientists. Does that make them equally dangerous?

Is professor emeritus Don Huber dangerous because he is a scientist?

The story of my professional life. It’s all too common that I take a phone call from someone who has a potential concern about some chemical listed on a product safety data sheet. Can I test to see if their employees are exposed to this chemical and is it safe?

And I have to tell them that theoretically I can sample for it. In reality I can’t help because there are no analytical standards for the chemical in question so step one would be funding a lab to develop a standard (~$30K). But after that sampling won’t really help make any decisions because there is no data on “safe” or “dangerous” levels of exposure. To get that we’d need to come up with another $100K to get an organization like the American conference of governments industrial hygienists (ACGIH) to do a study that produces a recommended exposure limit, but that won’t be binding in any way.

Even the well known things are problematic. OSHA limits of exposure mostly haven’t been updated since the late 70’s. In some cases they were set by the technical limits of analytical chemistry of the era. ACGIH’s recommended limit (sometimes NIOSH too) might be an order of magnitude lower than OSHA. But only OSHA is enforceable. This is the case for tens of thousands of chemicals.

I’m working on a DDT spill investigation right now. It was dumped decades ago and discovered last year, so not a recent event.

The NIOSH limit for DDT in soil is 50 ppb, for some flavors of the chlorobenzene carrier it is 5 ppb.

No updates since DDT’s ban would explain why the DDT limit is so high.

The limit is probably set high enough to where most DDT presences are at or under that limit. That way, they don’t have to be cleaned up or otherwise addressed, legally and regulatorily speaking.

I remember reading once a joke which in briefest goes like this:

The mafia was interviewing for an accountant. The final question for each candidate was ” how much is 2 + 2?” Each candidate answered ” 5 “. The mafia interviewer answered back: ” thanks, we’ll let you know.”

One day the mafia was interviewing yet another candidate and as per usual asked ” What is 2 + 2?”

When the candidate answered ” What would you like 2 + 2 to be?” . . . the mafia interviewer said “you’re hired”.

During the use of DDT, my family lived in Sarasota, across the Trail from the airport and just north of the Ringling properties.

Periodically the vehicles spraying DDT would pass through the neighborhood in the evenings. Fogging, I believe they called it. How often I cannot recall, but my duty was to run around and close the jalousie windows before the terrible smell would come into the house. But of course it did anyway.

In my neighborhood, we called those vehicles Stink Trucks. And we kids threw rocks at them.

I grew up in the 1960s and 1970s in a region similar to Sarasota. The fog trucks were probably spraying malathion instead of DDT.

Idiots that we were, we would sometimes follow the trucks on our bicycles, albeit on the side away from the sprayer. I remember one youth football game played in the evening when the truck came by and spread a cloud over one end of the field. The game was paused and we watched from the field while the fog dissipated. Of course, I also remember playing at night when lightning could be seen on the flat, coastal horizon…

The book apparently misses one important aspect of the DDT story: resistance. Populations of insect pests resistant to the effects of DDT started showing up soon after the widespread use of the pesticide. As the years went by the number of resistant pest species grew, and as new pesticides were developed, resistance to them appeared and increased as well.

I was an undergraduate major in Entomology at Cornell in the late 1960’s, just before DDT was finally banned. One of my professors told us that the pesticide industry was actually delighted with Rachel Carson because she allowed them to blame environmentalists instead of having to admit that by then resistance was so widespread that DDT had become functionally useless for most forms of pest control.

This is DDT-adjacent but relevant re: “How to Sell a Poison.” This week I attended a meeting with the director of the city’s parks department along with staff and community volunteers. They discussed spraying the park grounds to get rid of weeds. I asked what they used. Round-up. I noted that it causes cancer and oh BTW didn’t we learn during COVID that parks, greenways, and trails are part of the public health system so shouldn’t we find some alternatives that aren’t poisonous? Two-fold response: there’s nothing better to use and it’s safe when used according to the instructions on the label. (sigh) DDT created a template for selling poison as good for you (I grimaced when Okun noted the connection between Big Tobacco & DDT) and in the intervening years, weakened enforcement and massive campaign contributions have made it easy to sell. As Lambert puts it: because Markets + go die.

Once upon a time it seemed the Precautionary Principle was gaining traction (or at least was being discussed openly.) Nary a peep for quite some time.

I remember at the time learning that one of DDT’s mechanisms-of-deathdealing to the apex-predator birds was by interfering with the mother-birds’s calcium metabolism pathways, such that the birds found themselves laying eggs with gossamer shells or no shells at all, such that the birds crushed and killed the eggs by sitting on them to incubate them, leading to zero reproductive success. And removing DDT in particular from active use removed this calcium eggshell-prevention from happening, which allowed the apex predator birds to resume reproductive success through the non-crushing-to-death of eggs which had shells again.

This has lead me to wonder how much of the osteoporosis in today’s old people who were young at the time of DDT might be due to calcium metabolism derangement in humans due to DDT traces? Leading to mass osteoporosis in the generations of people exposed to steady 24-7 DDT marination?

Has anyone else wondered about that?

Check osteoporosis rates in other countries outside US and at different latitudes…

A couple decades back I heard a radio interview with a public works or parks manager (in a Virginia suburb of DC, I think), talking about insect control, etc. He shocked the interviewer by praising DDT, denying or minimizing its toxicity, and expressing deep contempt for “Silent Spring.” IIRC, he made a comparison of the number of “avoidable” malaria deaths that as much as said that Rachel Carson was worse than the Holocaust. He sounded like he really believed it. Sheesh!

Actually, this is what the numbers are revealing. I have a Masters in Occupational and Environmental Hygiene and DDT was studied in my program. The facts are in line with that public parks manager.

If one looks at the numbers, one finds that a bit of alcohol is actually beneficial for health and well being of individuals. Public health officials will not be found expressing this position publicly…

Is a bit of DDT beneficial for health and well being of individuals? What amount of DDT are you eating or drinking to personally enhance your individual health?

Just wait a bit for more warming, see how malaria starts spreading in the southern United States…

Is a bit of DDT beneficial for health and well being of individuals? What amount of DDT are you eating or drinking to personally enhance your individual health?

How did the US Panama Canal Zone authorities suppress yellow fever mosquitos down to completely zero in the Zone decades before the invention of DDT?

As far as I know, the effects on DDT that were quantified were the reduction in the eggshells thickness.

Yes, in 1950s and 1960s it was applied wantonly, as was done with other things, like asbestos. But we did deprive African states and tropical, equatorial states of a defense against malaria… And one needs to do a risk assessment for costs and benefits of using DDT. And those wanting to ban DDT will be found wanting… We don’t ban cancer drugs because they are all ultimately poisons…

Yet the approaching extinction of a number of keystone species with the continuing use of DDT is not important? Ecological collapse is a bad thing. Not to mention that DDT has a deleterious effect on people for decades and continues to do so with it being everywhere.

It might still be useful despite the gradual in resistance in the more rapidly evolving insect species populations, but just how are those wanting to ban it be wanting? There are other ways?

We don’t broadcast-spray cancer drugs over millions of square miles of land area.

I am astonished that apparently neither the book nor the commentariat seem to mention the most pernicious and lethal aspect of DDT, that the compound itself and its breakdown products are potent and long-lived (and lipid soluble) endocrine disruptors.

NCBIhttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov › articles › PMC8539486, et. al.

Initial studies on individual DDT breakdown compounds showed some degree of endocrine disruption. Researchers discovered combining minute doses of breakdown products produced synergistic endocrine disruption many orders of magnitude greater than by a single compound.

The large clustering of breast cancer cases on Long Island has been attributed to DDT spraying in the 1950s. Indeed I know several women with breast cancer (fortunately now in remission), who grew up on Long Island and ran behind the DDT spray trucks as children.

Cf. the scene in Terence Malick’s Tree of Life where Waco children frolic behind the DDT spray truck.