Yves here. We are departing (only mildly) from our usual programming to bring you this public service announcement. Perhaps I missed it, but I don’t recall seeing anything in the mainstream media about possible bad interactions between high ambient heat levels and widely used medications.

By Neha Pathak, an MD, FACP, DipABLMs, dual board-certified in internal medicine and lifestyle medicine who serves on the medical team responsible for ensuring the accuracy of health information on WebMD and reports on topics related to lifestyle, environmental, and climate change impacts on health. Pathak is co-founder of Georgia Clinicians for Climate Action and Co-Chair of the Global Sustainability Committee for the American College of Lifestyle Medicine. She is a Public Voices Fellow on the Climate Crisis with the Op-Ed Project and Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Originally published at Yale Climate Connections

Heat waves can be deadly. And experts worry that certain medications may make the danger even greater.

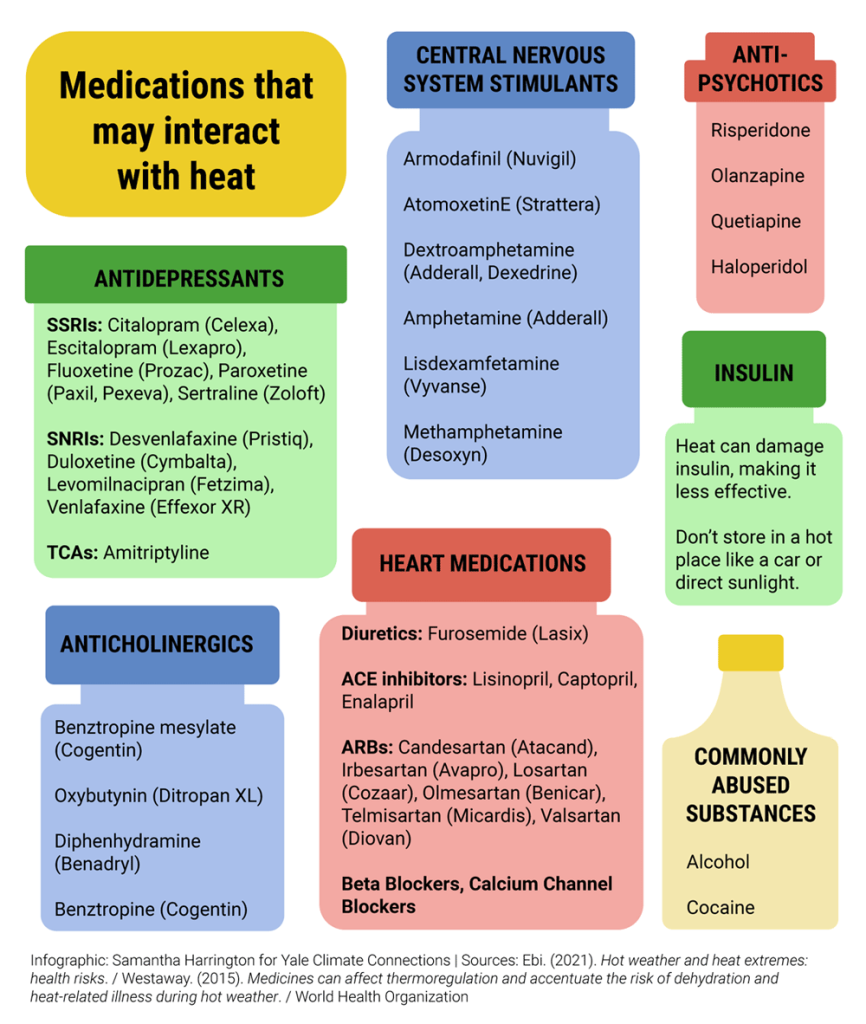

Tens of millions of Americans take one or more medications. And many common prescription and over-the-counter medicines, such as certain antidepressants, antipsychotics, antihistamines, and drugs used to treat diabetes and high blood pressure, may reduce the body’s ability to maintain a safe temperature.

The drugs may interfere with the body’s internal thermostat or impair sweating, according to a 2021 review in The Lancet, a peer-reviewed medical journal.

Kenneth Mueller, a pharmacist and clinical instructor at the Emory School of Nursing, says some medications can affect a person’s perception of heat and internal thermostat. And they can alter the body’s ability to redirect blood flow to the skin, a key way that it cools itself.

In hot weather, those side effects could increase the chance of life-threatening consequences, like severe dehydration or heat stroke.

“Doctors and pharmacists should warn patients about the potential dangers of [these] medicines during extreme heat events,” CDC spokesperson Bert Kelly wrote in an email.

Which Medications May Make Heat More Dangerous?

Antidepressants like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs, may increase sweating, increasing the risk of dehydration.

Others, like tricyclic antidepressants, or TCAs, may decrease sweating, making it harder to cool off.

Antipsychotics may impair sweating and alter the body’s internal thermostat.

Anticholinergic drugs, a large category of medications commonly used to treat an array of conditions such as urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, allergies, and Parkinson’s disease, may interfere with sweating and the body’s internal thermostat. They may also reduce blood flow to the skin.

Patients with heart disease may be prescribed multiple medicines, including diuretics and ACE inhibitors. Such drugs can cause dehydration, affect kidney function, and limit the body’s ability to redirect blood flow.

Mueller, the pharmacist, adds that dehydration may also pose risks.

Dehydration can increase the blood levels of some medications. Even slight increases can lead to toxic effects for certain drugs, such as lithium. These effects can range from tremors and weakness to agitation, confusion, and even death.

And some diabetes medications, including insulin, can lose their effectiveness in hot weather.

Who Is Most at Risk From the Interactions Between Medications and Heat?

Anyone can experience a heat-related illness.

But adults age 65 and older and those with chronic conditions are among the most vulnerable to extreme heat.

A study of a 2003 heat wave in France found a 40% increase in excess deaths for people over the age of 65 and a 70% increase in excess deaths for people over 85 during the event. Another found a higher risk of emergency hospitalizations among older people during a 2006 California heat wave.

Older people may be more sensitive to heat because as people age, their sense of thirst can decrease — and so can their ability to sweat.

People with chronic conditions like heart disease and diabetes are also more sensitive to heat. Heart disease can make it harder to move blood to the skin. Diabetes can reduce blood flow to the skin and reduce sweat production. Both processes are essential to keeping the body cool when temperatures rise.

On top of that, older people and those with chronic conditions are more likely to take medicines that lead to more urination and changes in sweating patterns.

Many people over the age of 65 take more than five medications. Some have medication lists in the double digits.

Sixty percent of Americans suffer from at least one chronic disease and 40% have two or more.

In a world of climate-fueled temperature spikes and lengthening summers, the combination of age, chronic disease, and medications can leave people vulnerable.

How to Protect Yourself in Hot Weather

If you are at higher risk for heat illness, particularly if you’re older and take medications for chronic conditions, monitor yourself for the first sign of heat stress: feeling dizzy, fatigued, or thirsty.

Make sure you have access to a cool place to rest. Drink non-alcoholic fluids regularly, though follow your doctor’s guidelines — drinking large amounts of plain water in a short amount of time can be dangerous because of the risk of electrolyte imbalance in some people.

Staying in frequent contact with family or other caregivers can also be lifesaving.

But experts interviewed for this article could not offer tips beyond being aware of the potential risks of medication and heat interactions.

“People are on medications because they need them. But what’s the right move when it gets hot out? Is it just stay inside and stay air-conditioned? Is it lower the dose by 10%?” asks pediatrician Aaron Bernstein, director of the Center for Climate Health and the Global Environment at Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. “We don’t know.”

More Research Needed to Understand Specifics

Ollie Jay, director of the University of Sydney’s Heat and Health Research Incubator, cautions that researchers have not completed systematic research that shows the exact connection between medications and heat risk.

Although a variety of studies show that people taking certain classes of medications are more likely to need emergency care and that there is a link between certain medications and a higher chance of death during extreme heat events, researchers have yet to perform “gold standard” experiments to demonstrate the exact effect of medications on the body’s ability to respond to heat.

Jay is at work on studies that monitor how an anticholinergic medicine may affect how people regulate their body temperature through sweating and changes in blood flow to the skin.

He adds that there is strong evidence that cocaine affects the sweat and skin blood flow response and reduces a person’s awareness of heat.

“So in terms of evidence for that type of drug, it’s clear, but the prescription medication, there’s not too much out there,” he says.

Bernstein, the pediatrician, agrees that more research is needed to make direct connections between specific prescription medications and the exact contribution to heat illness — and to understand whether the risks to people on multiple medicines are even higher.

“But we absolutely see people who are on these meds showing up in hospitals in greater numbers because the medication is affecting them,” he says.

Health Care Workers Have More to Learn

Another challenge: Many health care workers are not aware of the risks of heat and medication interactions. Most do not routinely counsel their patients about how to stay safe.

Cheryl Holder, a primary care physician in Miami, Florida, was tapped in 2021 to co-chair Miami-Dade County’s nascent Climate and Heat Health Task Force. Now Holder wants to ensure that the task force works to develop a local heat action plan that educates the public and health professionals about the health risks from heat, including those from medications.

“Many physicians here have made some of the general changes, where most docs don’t do a lot of diuretics for patients who have to work outdoors,” she says. Because diuretics, commonly known as water pills, can lead to dehydration, their use is especially concerning during heat waves.

“But in terms of a full awareness of the excess mortality and better preparation, we’re just starting to work,” she says.

A recent study (nature.com/articles/s41380-022-01661-0 ) said “Our comprehensive review of the major strands of research on serotonin shows there is no convincing evidence that depression is associated with, or caused by, lower serotonin concentrations or activity.”

So maybe the best approach for dealing with thermal regulation problems from SSRIs is to just stop taking SSRIs

As if. My reading of that study (or at least the synopsis) is that while the mechanism is in doubt the association of the drugs with improvement in the depressed state is not in doubt, in other words we don’t know why they work. Further, abrupt withdrawal from SSRIs is decidedly unpleasant. The best approach we have now is to be aware and monitor hydration – drink water!

“the association of the drugs with improvement in the depressed state is not in doubt”. I wouldn’t be so sure. I also ran across an older article about a study that concluded “antidepressants are largely ineffective and potentially harmful”.

I recommend that anyone prescribed SSRIs make an extended search of the literature, and make their own conclusions.

Your statement is false.

1. SSRIs perform only at placebo levels.

2. SSRIs clinical trials are effectively unblinded since the participant must be informed of a whole host of possible SSRI side effects, so when they get them, they know they got the drug, not the placebo.

Please be careful, there is a very high risk of suicidal behavior during the tapering phase of a course of SSRI medication. I lost a friend to this very phenomenon years ago. Went off an SSRI cold turkey and promptly shot himself. These are dangerous and ineffective medications.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/your-brain-food/202207/evidence-serotonin-failure-does-not-cause-depression

Thank you, that’s a critically important point I hadn’t been aware of.

Another point is that going off SSRIs can cause withdrawal, called “discontinuation syndrome.” Interesting that, the language – not withdarawal symptoms but discontinuation symptoms.

At what temperature is the heat excessive and a health risk? The reason I ask is that when we lived in the States, 85F was a perfect summer day but here in Norway it’s sweltering. People here walk around in T-shirts in fifty degree (F) temperatures, whereas people in more southern climes would be wearing winter jackets.

That said, thanks for the post. I was put on a diuretic after my diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension and have been concerned about dehydration. I’m also on a blood thinner because of a pulmonary embolism and a calcium channel blocker for my SVT (ailments for which I suspect the Covid vaccines but can never prove it.)

Effective cooling via evaporation, exploiting water’s high heat capacity, depends on both absolute temperature and humidity (so-called wet bulb temperature TW; at 100% relative humidity, wet and dry bulb temperatures are equivalent). Under saturated conditions, 35°C appears to be the limit:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aaw1838

This is when you learn what iatrogenesis is.

Yes, this definitely is a good public health message. Gratefully received. Thank you!