Yves here. I am a bit surprised to see the assertion in this piece, that there has been relatively little work done on the political effects of financial crises. I recall reading and being told more than once after 2008 that the typical response, in the absence of government action to alleviate the pain, is a strong shift to the right, which we’ve seen in Europe and the US.

By Luigi Guiso, Axa Professor of Household Finance, Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance; CEPR Research Fellow; Massimo Morelli, Professor of Political Science and Economics, Bocconi University; Tommaso Sonno, Assistant Professor, University of Bologna. and Helios Herrera, Professor of Economics, University of Warwick. Director CEPR POE Programme. Originally published at VoxEU

Financial crises have severe economic costs. This column shows that they also entail major political costs. It argues that the global financial crisis, and associated Great Recession, represents a watershed for populism in Europe, changing people’s views and the rhetoric of all parties. The crisis brought economic insecurity to the middle classes, which had largely remained untouched by the globalisation and immigration shocks. Disillusionment with the status quo prompted parties to enter the political arena on populist platforms.

Financial crises are a recurrent phenomenon in the history of emerging markets and advanced economies alike. However, there has not been much research into their consequences outside the realm of economic variables. Generally, there is still limited knowledge on the political economy of financial crises – exceptions include the contributions by Fernandez-Villaverde et al. (2013a, 2013b), McCarthy et al. (2013), and Mian et al. (2010a, 2010b, 2012, 2014).

In a recent paper (Guiso et al. 2022), we argue that the 2008 financial crisis and the associated Great Recession were a major factor in the spread of populism in Europe in the 21st century.

Much has been written about the role played by the onset of globalisation and automation which, by causing job losses mostly in low-skilled sectors, created disillusion in voters in liberal democracies, gradually changing in the demand for policies. For instance, Rodrik (2018) traces the origin of today’s populism to the globalisation shock, while Autor (2020, and references therein), Colantone and Stanig (2018a, 2018b), and Jensen and Bang (2017) are clear examples of well-identified effects of the China shock on specific manifestations such as Brexit.

In these studies, the financial crisis is treated as another factor that further enhanced voters’ appetite for populist policies, without focusing much on the exact mechanism and on which segment of society was most affected by it – see, for instance, the review by Dani Rodrik here on Vox (Rodrick 2019).

Financial Crises Are Fundamentally Different from Globalisation and Automation Shocks

In fact, financial crises differ from globalisation and automation, which are gradual and perhaps irreversible trends. Financial crises are acute business cycle events – sudden breaks that trigger more sudden political consequences, which turn out to be more pervasive as well. But most importantly, financial crises, despite generating sharp downturns that fade in the medium term, may have political consequences that outlast them.

While globalisation and automation create losers, there is no doubt that there are also winners. Furthermore, global trade has meant not only job destruction and lower wages for blue-collar workers in firms hit by foreign competition, but also lower prices for the final goods entering consumers’ consumption bundle (and firms’ intermediate inputs). This is not true for financial crises. Recessions induced by a financial crisis largely lack beneficial effects – most people, across the spectrum of the voting population, lose. Income losses tend to be deep and universal. Hence, the discontent fostered by the ensuing economic insecurity tends to be more pervasive and thus politically relevant.

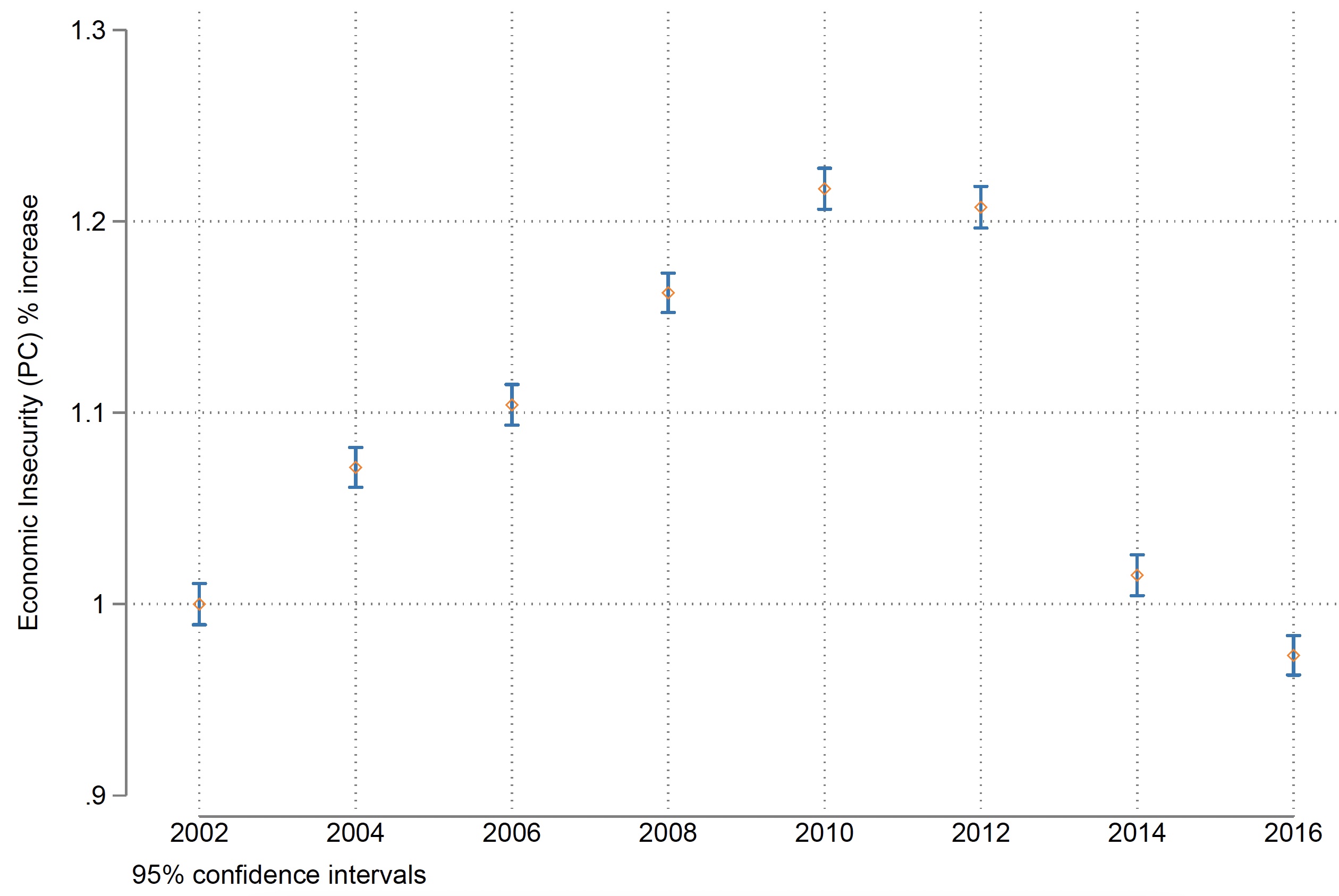

Figure 1 plots a measure of the evolution of average economic insecurity in the 28 European countries covered by the European Social Survey (ESS), setting its level at one in 2002 (the first sample year). While economic insecurity had already increased in the years before the financial crisis when globalisation was unfolding, it spikes in the years of the Great Recession and the European sovereign debt crisis, but then drops sharply after the crisis in 2014. Globalisation and robotisation, which are secular trends not business cycle phenomena, cannot explain this drop.

Figure 1 Economic insecurity

Notes: The graph plots the evolution of a measure of average economic insecurity (and its 95% confidence interval) in the 28 European countries covered by the European Social Survey. Its level is set to one in 2002.

Effect on the Middle Class

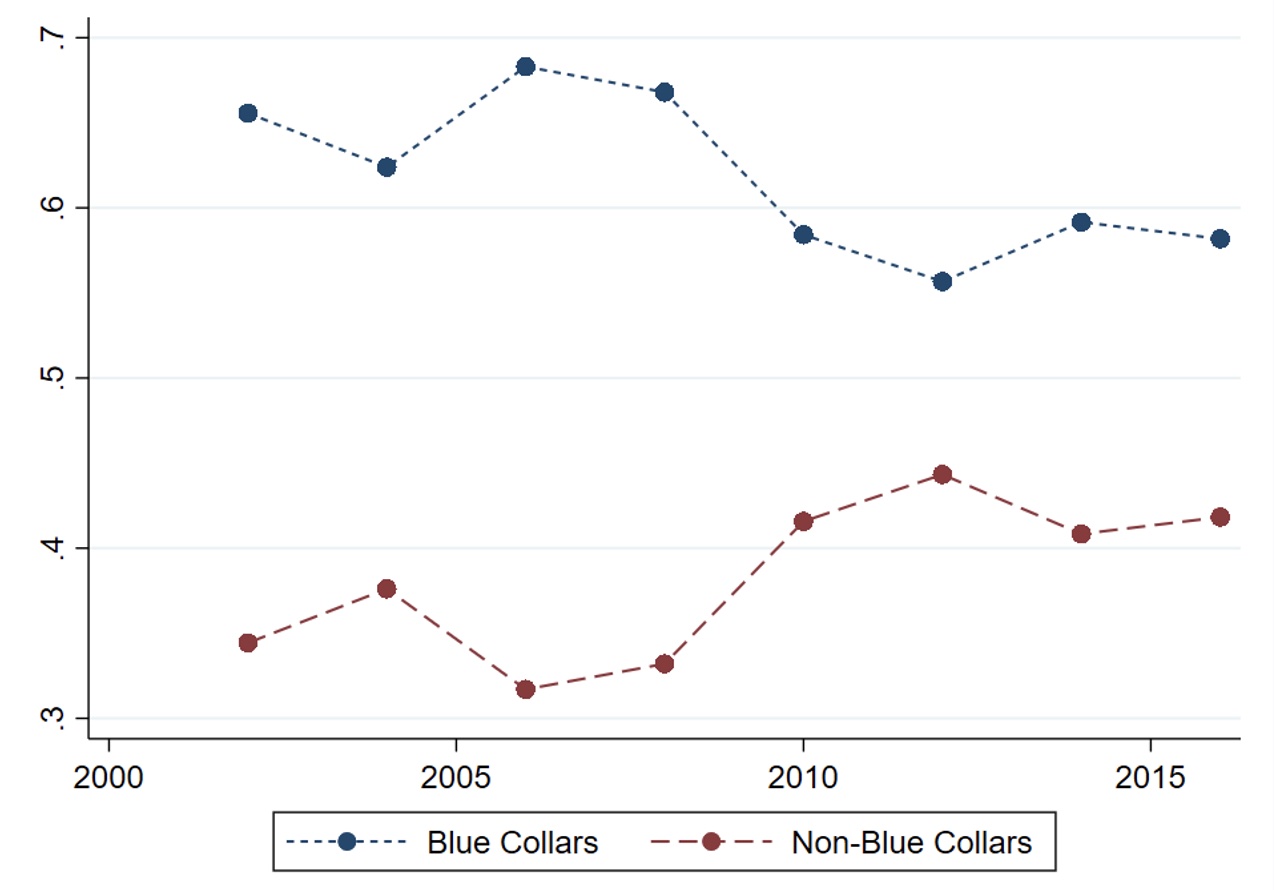

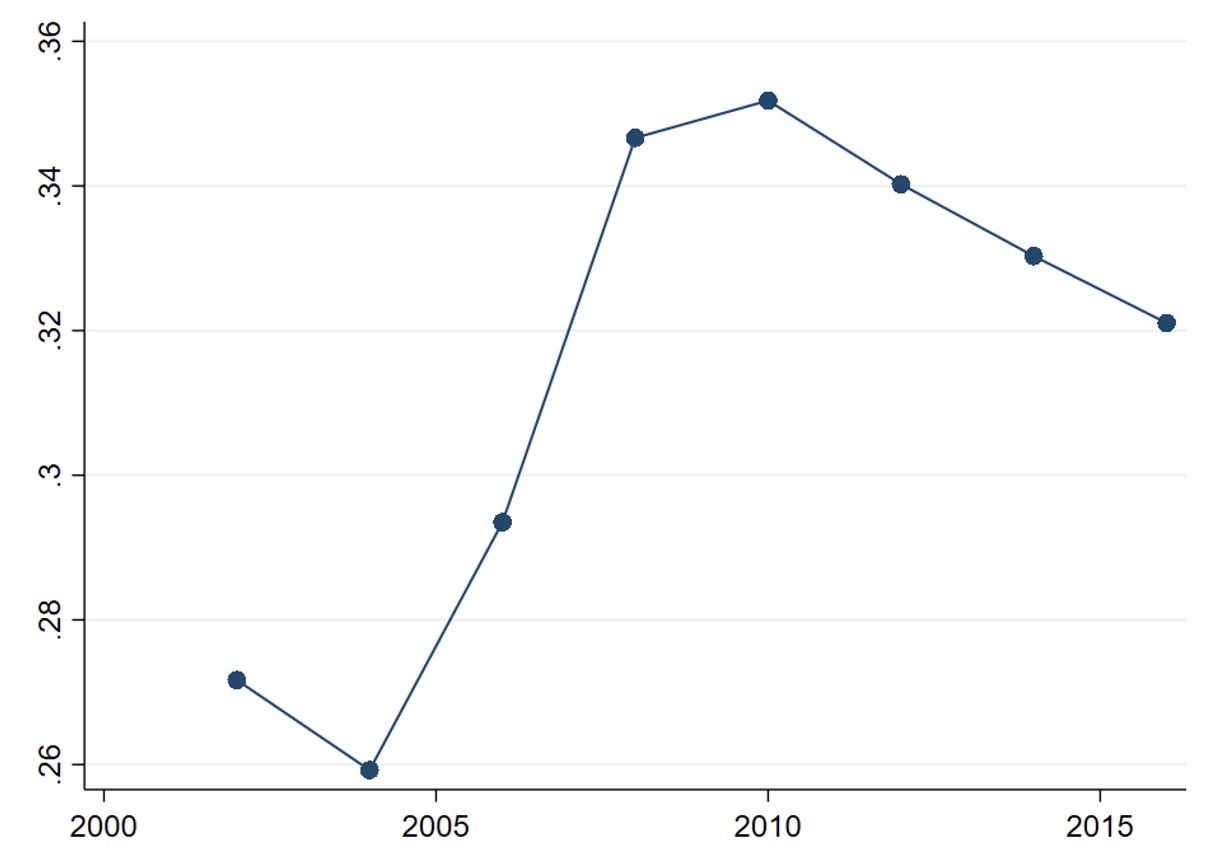

The composition of those suffering serious insecurity also changed after the onset of the crisis in 2008 and extended to segments of the population that were less hit by the globalisation shock. Figure 2, Panel A shows the share of blue and non-blue collars in the top quartile of economic insecurity in each year of our sample. Prior to the financial crisis, in the years of the globalisation wave, the incidence of blue-collar workers among those experiencing high insecurity is dominant (66% on average); in the years after 2008, the share of non-blue-collar workers increases substantially, by more than eight percentage points compared to the pre-financial crisis years. Panel B shows that the financial crisis injected economic insecurity in the middle class as well (defined as people in the middle 50% of the income distribution of income in each country-wave). The share of middle-class voters suffering serious insecurity (i.e. in the top quartile of insecurity) climbs rapidly in the years of the Great Recession. Thus, the financial crisis not only increased insecurity among social strata that were already distressed by globalisation and the like prior to the crisis (typically blue collars and low-skill workers at the bottom of the income distribution), but also extended insecurity to segments of the population that had been more sheltered from globalisation.

Figure 2 Economic insecurity: Blue-collar and middle-class

A) Blue collar

B) Middle class

Notes: Panel A plots the share of blue and non-blue collars in the top quartile of economic insecurity in the years of our sample. Panel B shows the share of people in the middle 50% of the distribution of income in each country-wave.

Borrowing Constraints Are Key

Importantly for economies like those of the advanced Western countries where both firms and households are heavily dependent on finance, financial collapses are particularly hard to cope with. One important mechanism to buffer income shocks in these economies – borrowing in the market – is hampered by crisis, as financial markets stop working smoothly and financial constraints become more binding. In addition, the fall in asset prices caused by the crises impoverishes any precautionary savings workers may have accumulated, limiting their capacity to deal with economic insecurity.

Our main point is that the European financial crisis created new classes of disillusioned voters. The economic insecurity triggered by the financial crisis had a causal effect on voters’ trust in political parties, on turnout, and on voting choices. We also document an increase in abstention especially among those who had not already been hit hard by globalisation.

Causality

Financial crises are most damaging for people that depend more on borrowing to buffer income shocks and thus to manage economic insecurity. Financial shocks hamper the ability to borrow of people dependent on credit. These are often individuals that also belong to segments of the middle class, thereby significantly enlarging the pool of voters who seek protection and doubt that the status quo governance of the economy can deliver it. In turn, dependence on borrowing varies across individuals as a function of the steepness of their age-earnings profile: people with a steeper profile must rely more on borrowing to smooth consumption, which makes them more vulnerable to financial shocks.

In our pseudo-panel analysis, different cohorts of respondents to the European Social Survey over time and across countries have different compositions in terms of occupation, and different occupations display marked differences in the steepness of age-earnings profiles. Hence, different occupations display heterogeneous sensitivity to a financial crisis. Using heterogeneity in the steepness of income profiles, we construct a shift-share instrument where the shifter is the aggregate economic shock affecting a country, and the share determining the sensitivity of each cohort is the weighted average sensitivity in the cohort, using as weights the shares of the different occupations in the cohort.

The effects on voters’ behaviour along all three dimensions are relevant: a one standard deviation in economic insecurity (i) causes an increase in populist voting of seven percentage points, around 94% of the sample mean; (ii) lowers turnout by more than eight percentage points (about 10% of the sample mean); and (iii) lowers trust in political parties by as much as 35% of the sample mean.

Supply-Side Evidence

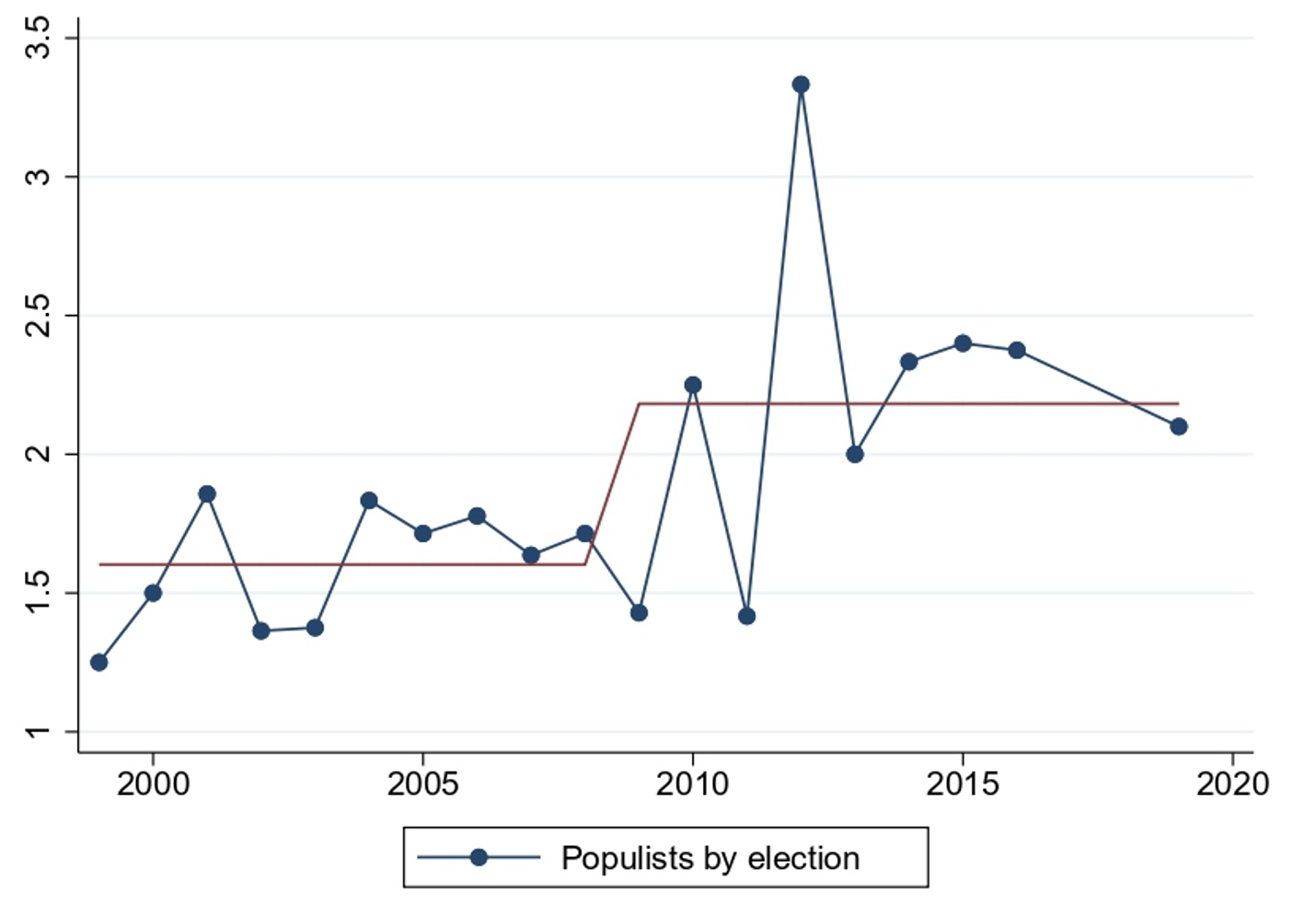

Our analysis suggests that the financial crisis broadened the pool of disappointed voters, prompting, on the supply side, political parties to enter the political arena with platforms giving the disillusioned voters a new hope for simple and monitorable protection. Indeed, the moment of maximum entry and transformation of parties in Europe is in this period.

Figure 3 plots the average number of populist parties showing up in elections up to 2008 and in the years since the onset of the Great Recession. It is clear that the Great Recession marks a watershed in terms of supply of populist parties competing for votes. Up until 2008, the number of populist parties running in an election was around 1.7, with no clear trend. In the years following 2008, the average number of populists available for vote jumps to 2.4 – a 33% increase compared to the pre-crisis mean – with a spike in the 2012 elections. Again, the financial crisis seems to constitute a structural break in the supply of populist platforms.

Figure 3 Populist parties

Notes: The graph shows number of populist parties (blue line) and the average number of populist parties (red line) showing up in elections.

A novel analysis of the dynamics of the supply of populism in Europe, looking at the manifestos for all European parties and distinguishing long-lived parties (present both before and after the financial crisis) from parties that died or were born with the crisis, confirms that much of the exit of old parties and entry of new populist parties, as well as much of the transformation of platforms of parties that became populist but were not counted as such before, happened after the financial crisis.

Concluding Remarks

We argue that the financial crisis was a tipping point that has transformed politics in Europe, on the demand as well as on the supply side. The fact that since the crisis (i.e. after 2014), populism has persisted in Europe suggests that it created a structural break – a tipping point which is hard to recover from – by changing people’s views and the rhetoric of all parties. It remains to be seen whether this wave of populism will transform politics in Europe permanently – a possibility that studies of past historical episodes suggest cannot be ruled out (Funke et al. 2021).

See original post for references

I hate to see the word ‘populism’ used for ‘rise of boorish foolish incompetent demagogues’. Real populism would be a good thing. Guess the word will now be another slur like ‘radical left’ etc.

Monetary stimulus and tax policy are matters of political will and directed resultant activity.

As to populism, I concur. It’s like Anarchist being assumed to be a radical bomb thrower, as opposed to a legitimate school of thought – a form of deeper Libertarian thinking. A true anarchist would disdain and be appalled at the thought of throwing a bomb into a crowd.

Was the burning of a schmancy over-the-top mountain top restaurant at Vail resorts at night, with no souls present in the building, Terrorism, or Arson? Words should matter.

Our oldest kid, now mid-30’s had a slow-go-through college, and graduated into the depths of the post-2008 depression. As he points out, he lost a decade of earnings, typical job/ career mobility.

Then, just as he gets a bit of wind under his wings, Covid depression/ inflation etc.

Another decade starting of more lost ground. He is not alone, we are all dealing with this in one form or another.

And maybe, hard as this is to see and say as a parent and fellow spaceship erf passenger… we all need to tighten belts, skip meals, change habits, and expectations.

Monetary stimulus and tax policy are matters of political will and directed resultant activity.

Covid and the climate disaster presented opportunities to ruminate, ponder, and create a new consciousness and direction shift. We had a Global Moment. Yet TPTB and many folks simply wanted a ‘return to normal’.

I personally wish we would have, globally and collectively, expended all those phantom but meaningful monies into a new Green Economy moon-shot. 10 hr work week, shared jobs, and sustainable lives and activities.

Haw Haw Haw! Silly Me!

Can’t wait to hear what those running for office in 2022 ‘promise’ as priorities.

Central banks have fetishized independence. They are set up NOT to be influenced by political pressures. The fact that they are cognitively captured by finance may produce similar-seeming results, but what suits Big Money does not suit a lot of Real Economy constituencies.

Central banks are in thrall to monetary models that are based on proven to be bogus concepts, like the loanable funds theory.

Yes, I am coming around to the conclusion that central bank “independence” is part of the architecture of an economic regime which is hostile to labour and used in particular to shield our elected representatives from accountability as they increasingly govern on behalf of their donors rather than their constituents — and that participation in this charade by the erstwhile “parties of labour” (US Democrats, UK Labour, Australian Labour, European Social Democrats) represents an ongoing betrayal which accounts for their increasingly dismal electoral performance with their original support among the working classes.

All part of the “TINA” (there is no alternative) ratchet.

Yep. Where are the representatives of labor on the Fed’s board (for one thing)?

The Fed serves “labor discipline” — the message that you had better take whatever crappy job is on offer or suffer the indignities of poverty, perhaps even homelessness and starvation. And if you’re extra ornery, we’ll put you in a cage. It’s the whip in the hands of the plutocracy.

Yes. Would someone please define what Populism is? As above, the Populist movement and parties in the US were reformers in response to the abuses of the railroads, the trusts, the banks, Wall Street, etc. They brought positive changes. Here in Spain, after 15-M (similar to the Occupy Wall Street movement but several months earlier) a number of left of center, reformist parties arose that the press called Populist, or anti-sistema. It was a perjorative. One of which, Podemos, has survived and is an actual progressive force in the government. An extreme right-wing party, Vox, has also become strong in recent years. BOTH are described as Populist. Throwing them in the same bag for this analysis is beyond stupid. The dominance of the two major parties in Spain – bipartidismo – seems to be gone forever. I would suggest that Populism simply means Something Diffferent. In the lingo of this blog, it means whatever is opposed to the rule of the PMC. As the article above points out, when things go bad, obviously people will want something diffferent. If only the US could develop a third (or even a second) political party.

This article is also a perfect example of another of the items for today, ¨There is no Nobel Prize for Economics¨. The authors of the financial crisis story insist on quoting studies that prove what everyone already knows, trotting out graphs and references (thankfully, no statistical analysis) to be sceintific, to prove nothing. If they had bothered, or were able, to distinguish what flavor of populism they were refering to it might have been useful.

From The Nation:

The terms “populism” and “populist” are not well-defined. Indeed, many terms with regards to political ideology are vague and have fuzzy references. Very often populism has a negative connotation, perhaps because it challenges the once all prevalent geoculture of the capitalist system which was based on liberalism, both conservative and social democratic.

I agree that “real populism” is a good thing just like “real nationalism” is a good thing. We need to acknowledge that solutions are important and if they are not produced in a timely manner we all suffer more and get angry. So when our own Congress is so clueless and imperious as to ignore the needs of society, we look for a change. Usually its some charismatic guy like Donald Trump. Last nite I watched a June Interview (PBS) with Francis Fukuyama. And he was so basic and clear thinking I wondered how he ever entitled his book ‘The End of History’. He went so far as to explain himself on Liberalism – that Liberalism had overshot its goal with neoliberal policies and in the 1980s began to create its own nemesis with all the financial innovation that was nuts and quickly spun out of control, and other stuff. Making me think that “finance” takes on a life of its own. Because, gosh, it’s a Free Market. Or maybe by the natural force of exponentiation – who knows? Like the Universe expanding at an ever-excellerating rate. Still that’s no excuse for agnotology. We need good solutions. I think price controls would be a good place to start – but please don’t call it populism.

So just to add that Fukuyama was saying simply that neoliberalism and free market lenience precluded good democracy – making democracy secondary to “the market” which effectively destroys democracy altogether and thus, without a functioning democracy, the very ideals of liberalism itself quickly erode. Liberalism is predicated on democracy, not free markets. So one question is, can financial crises and inequities be resolved in a “free market?” It really does not seem so from our recent experience with finance – but (me here) Congress could address this problem head on if they had two brain cells to rub together. We never hear any such deliberations, including about the recent blurb that Congress was writing a bill to give the Fed an expanded mandate that required the Fed to only use methods that did not cause inequality – I’d think it would be better to ask them to actually prevent and remediate financial inequality.

Perhaps a new word for what I think it is that you want could be . . . populeftism.

Apropos this post: The song Shipbuilding.

The Robert Wyatt version:

Is it worth it? Hard choices.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=MZ2DdrTPY58

——-

Is it worth it?

A new winter coat and shoes for the wife

And a bicycle on the boy’s birthday.

It’s just a rumor that was spread around town

By the women and children, soon we’ll be shipbuilding

Well I ask you

The boy said ‘Dad, they’re going to take me to task

But I’ll be home by Christmas.

It’s just a rumor that was spread around town

Somebody said that someone got filled in

For saying that people get killed in

The results of their shipbuilding.

With all the will in the world

Diving for dear life

When we could be diving for pearls.

It’s just a rumor that was spread around town

A telegram for a picture postcard

Within weeks they’ll be reopening the shipyard

And notifying the next of kin

Once again.

It’s all we’re skilled in

We will be shipbuilding.

With all the will in the world

Diving for dear life

When we could be diving for pearls.

Any opportunity to cheer Robert Wyatt must be indulged. One of my favorite musicians from the glorious Canterbury scene. BTW, check out his collaborations with the UK band Ultramarin.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lPyiW_16_nc

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CMP3J2clYx8

Eccentric, very British, my cup of tea…

Populism can be either left or right. At the far end of the spectrum we get Hilter and the 1918 revolutions in Russia plus Chairman Mao and the Kymer Rouge. At the more benign left-center of US populism we get the Grange movement, William Jennings Bryan and FDR. At the right center we get (dare I say it?) Ronald Reagan. What all have in common is a spontaneous upwelling of support from the disaffected.

So if the article is correct, slow shocks to manufacturing workers can be contained and ignored. But a financial crisis that means the middle class can’t borrow money at reasonable rates and may even be at risk of falling out of the middle class… oh, the horror! Even professional economists may be effected.

Accidentally listened to a A.M. conservative talk radio the other day. Came in the middle of the program and am paraphrasing what I heard. Couldn’t take notes while driving.

Radio host was talking about the “Regular Republican Party”, Mitt Romney etc, whose interests have been moving the embassy to Jerusalem, abortion, lower taxes for billionaires and the ‘latest addition’ waving Ukrainian flags’.

However, he went on, “There’s the developing ‘Populist Republican Party’, that is serving the real interests of Americans and also is fighting the Democrats and elite.”

I like the sound of that.

But is the Populist Republican Party fighting the billionaire donors who support the Populist Republican Party? Like that computer billionaire family whose name I forget who gave lots of money to Steve Bannon to get his Breitbart buildup and Trump buildup projects going?

Financial crises tend to expose the illusion of money as neutral and apolitical.

As Adam Tooze has argued, the 2008 crisis revealed the political ramifications of the power to create money. He has maintained that the U.S. Federal Reserve become the world’s defacto Central Bank noting the observation of a European Central banker that “we have become the thirteenth Federal Reserve District.”

We may now be in a period of Central Bank capitalism where the ascendency of finance has shifted the locus of sovereignty in our domestic politics.

typical it can’t be free trade, we know it works because the deplorable get cheap stuff. never mind that the cheap stuff comes at a very high price, you lose your standard of living and technology, not so cheap now is it!

the authors also miss the facts about germanies right ward tilt after Gerhard Shroeder sold out the german worker on the alter of free trade to accrue trade surpluses.

Sarkozy was a fraud, but he spoke out against free trade well before brexit.

https://www.rt.com/news/sarkozy-election-immigration-right-369/amp/

“And when Sarkozy is ranting against free trade and immigration, he is really advocating for more protectionism, Korbel believes.”

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/banana-republic-usa-popul_b_451182

” Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi has little in common with the likes of Hugo Chavez. Yet, many have referred to the billionaire media mogul turned politician as a populist, albeit of the rightist variety. ”

the authors ignore the fact that a financial meltdown in 2008, can be directly tied to the financial meltdown of the blue collar workers who could no longer service their debts, consume, save a little, and enjoy a few days off to savor the fruits of their labors under free trade.

when that happens, the inevitable financial blowout happens.

Free Trade is the new Slavery.

Protectionism is the new Abolition.

Whoa! This goes to show that labels – Populism, Socialism, Communist, Fascist – actually conceal more than they reveal. What matters is the program, the details, th principals (¨and if you don´t like those principals, I´ve got others¨ as per G. Marx). The war in Ucraine is just one of the events that illustrates how mixed up out political groupings are. The left and right are each rummaging throough their sets of principals, many of which are contradictory, to decide how tto align themselves politically. We live in interesting times. Not to get too metaphysical, but the constellations of principals that have arranged themselves into various political ideologies, or belief systems, are being rearranged. We can no longer rely on generalizations.