Yves here. It looks as if John Helmer could create a new sideline in eviscerating books by self-styled Western experts on Russia…that rely heavily on other self-styled Western experts who don’t know all that much about the subject at hand but gossip convincingly. Here the object of inquiry is Vladimir Putin and the experts consist heavily of spooks.

This dearth of knowledge sadly does not come as a complete surprise. Scott Ritter, who actually did Russian studies as part of his education, had oft said those departments have changed from helping Americans and Europeans master the language and develop an appreciation for the culture through history, literature, and music, to departments of “Putin-hating studies.”

But it gets even weirder in this case. Author Philip Short was a BBC correspondent many years ago, in Moscow, presumably in the 1970s (he’s not said when). How is it possible for such an individual to get his CIA and MI6 interviews without sponsorship, particularly since some of the CIA and MI6 names do not appear to have been published before? Who is behind his list?

It’s also, erm, unusual for a bio of Russian figure to have so much sourcing from the Balts — Sweden, Finland, Latvia, Estonia. And yet, for Short’s reported connections he seems to know nothing about the very big Finland and Estonian connections to oil shipping out of St. Petersburg.

By John Helmer who has been the longest continuously serving foreign correspondent in Russia, and the only western journalist to have directed his own bureau independent of single national or commercial ties. Helmer has also been a professor of political science, and advisor to government heads in Greece, the United States, and Asia. Originally published at Dances with Bears

Philip Short, a journalist from the BBC, has published a new book which claims to be a biography of Vladimir Putin. It isn’t.

What it is instead is a biography of one hundred and twenty-three westerners — what they claim to know about Russia’s leader and what for commercial motive, reason of state, or vanity they have told Short in interviews he conducted for his book. They include spies he names without their cover – John Scarlett, Richard Dearlove, Richard Bridge, Kate Horner, Martin Nicholson, and Pablo Miller from the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6); Hans-Georg Wieck and August Hanning of the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND); Jean-Francois Clair, Raymond Nart, and Yves Bonnet of the Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire (DST); Seppo Tiitinen of the Finnish Security Intelligence Service (SUPO); Mark Kelton, Michael Morell, Peter Clement, Michael Sulick, Michael Morgan, Paul Kolbe, and William Green of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA); Juri Pihl, head of the Estonian Internal Security Service, and Eerik-Niiles Kross, chief of Estonian intelligence; and several dozen other ambassadors, consuls, advisers, headquarters staff, journalists, and think-tankers.

Not one of the spies was operational in Moscow for the past twenty-one years of Putin’s terms in office.

There is a flash of originality in this book. Not a single source on which Catherine Belton’s book on Putin relies has been interviewed by Short; in his references to Belton’s claims Short reports they “appear to be untrue”. He reaches the same conclusion about two other books about Putin, Karen Dawisha’s and Masha Gessen’s. “Neither book pretends to be a balanced account”, Short says. Dawisha’s book “is marred by numerous errors of fact”. “All three”, Short warns, “set out the case for the prosecution, and like all prosecutors, the authors select their evidence accordingly.”

“Readers must decide for themselves,” Short concludes his book, “what is plausible, what sounds false, what rings true and what does not.” This is how Short ends on page 679 with what most biographers begin on page 1.

Left, the book published in the UK and US this month.

Centre: Philip Short who was a BBC correspondent between 1973 and 1998. Right: for more on the mind of Putin the mnemonist, and the Soviet cognitive psychology classic which first identified how such prodigious memory works, read this.

Instead, at Short’s beginning he trots out the old cliché of Russian politics written by westerners – that’s the canine definition of Kremlinology attributed to Winston Churchill as watching “a bulldog fight under a rug – an outsider only hears the growling, and when he sees the bones fly out from beneath it is obvious who won”. Short admits this isn’t new. “[It’s been] true of Russian governance since the sixteenth century. The Kremlin does not yield its details easily. The broad outline may be clear but the devil is in the details and the details matter. If enough details change, the overall picture changes too.”

Between this opening fatuity and his concluding one, Short has compiled a long list of fatuities about Putin. Since the espionage agents who provided Short with his interviews didn’t work in Russia after Putin took power, the fatuities are hearsay by at least six degrees of separation.

On the positive side of Short’s character ledger, there are Putin’s self-discipline, loyalty to friends, shyness, loneliness, indifference to money, love of sport, and his “excellent memory”, “brilliant memory”, and “unusually retentive memory”. On the negative side of the ledger, there are his secretiveness, unpunctuality, inconsiderateness towards women, calculation, repressed emotions, sensitivity to his short stature, taste for luxury, and “obsessive self-control”.

Their combination in Putin’s character was an immaculate conception, according to Short. “Even as a child,” he recounts, “Volodya Putin had concealed his hand; as a young nman, he did not vouchsafe information unless there was good reason. Putin’s time with the special services influenced his thinking and equipped him with new tools with which to view the world. But it did so by accretion. Putin was already Putin before he joined the KGB.”

For his evidence Short interviewed one-third as many Russians as westerners. The majority of the Russians are or were journalists; none of the remainder is from a Kremlin, Russian government, intelligence or military position during Putin’s presidential terms except for Mikhail Kasyanov, prime minister from 2001 to 2004, and Andrei Illarionov, an economic advisor between 2001 and 2005. The others are from the Yeltsin administration; they were, still are uniformly Yeltsin supporters hostile to Putin — except for Mikhail Delyagin and Yury Boldyrev.

With sources like these, it is little wonder the violent constitutional battle between Boris Yeltsin and the Russian parliament of October 1993 is described by Short as being fought on the anti-Yeltsin side by a “hard core of 150 deputies…protected by an armed militia of Cossacks, Chechens, Afghan veterans and far-right nationalist thugs.”

Not a single Russian business figure or oligarch has been included in Short’s Russian interview list – with a sole exception. He interviewed three members from the aluminium oligarch Oleg Deripaska’s payroll. Short’s version of Putin’s record on the domestic economy and the oligarch businesses follows Deripaska on metals; Mikhail Khodorkovsky on oil, Yukos and Rosneft; William Browder on gas and Gazprom; Illarionov on the financial collapse of 1998.

The snippets Short composes of other Russian characters in the story are also fatuities, but he leaves no doubt which ones he intends his readers not to take a liking to, and vice versa. For instance, Yevgeny Primakov, head of the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), foreign and prime minister in the 1990s – until removed on US orders — appears 51 times; he is introduced as “a bespectacled academic with jowls like a basset hound…a tough, pragmatic conservative”; Khodorkovsky appears 82 times as “short and solidly built, ten years younger than Putin, he had close-cropped black hair beginning to grey and, behind rimless spectacles, a gaze whose intensity gave him the appearance of a youthful nineteenth-century anarchist.” Alexei Navalny appears 99 times in Short’s book as “35 years old, a tall, slim man with Nordic good looks – dark hair and piercing blue eyes, who…had a knack of skewering the elite with pungent phrases that lodged in people’s minds and was refreshingly direct.” The numbers signify Short’s measurement of their impact on Putin’s history over the past thirty years. A westerners’ measurement, not a Russian one.

Oddly, Short doesn’t mention that both Primakov (Finkelstein) and Khodorkovsky were Jewish. He does make a point of claiming, inaccurately, that Jews were barred from the KGB. He also makes another point of emphasizing the Jewish origin of Galina Starovoitova, the Soviet dissident and liberal politician assassinated in November 1998, when Putin was head of the Federal Security Service (FSB). Short claims the killing was part of “a wave of anti-Semitism, whipped up by ultra-nationalist members of [Vladimir] Zhirinovsky’s party in the Duma.” Zhirinovsky’s Jewishness (Eidelshtein) is omitted from this story.

So convinced of the stories Short retells of Primakov’s malign influence it didn’t occur to him to check with Primakov, who was alive when Short began his interviews; or his presidential campaign partner Moscow mayor Yury Luzhkov, alive until 2019; or any one of their associates and advisers. No one on the Russian left was interviewed directly or indirectly at all. Dmitry Rogozin — Putin’s appointee as NATO ambassador, deputy prime minister in charge of defence, and head of Roscosmos — was disposed of by Short as “a solidly built right-wing firebrand whose rhetoric attracted malcontents both from the far left and from extreme far-right groups.” The meaning of left and right in Short’s vocabulary is unexplained, taken for granted to mean anti-western. Sergei Glazyev, the leader of the left economic line in Putin’s Kremlin is not mentioned at all. By contrast, Alexei Kudrin, on the right, is reported 33 times; Anatoly Chubais, 57 times. Short reports interviewing his brother Igor Chubais, but not what he said.

Short repeats what he has read of the stories already published of Putin’s time in Dresden, then in Mayor Anatoly Sobchak’s administration in St. Petersburg. His version of Putin’s rise in the Kremlin follows what he was told in his interviews and by the published version of Konstantin Yumashev, Yeltsin’s bagman, son-in-law, ghost writer. Nothing new.

Nor is Short’s discovery of what he thinks is new evidence. For Short’s conclusion that Putin ordered the polonium poisoning in London in November 2006 of Alexander Litvinenko he refers to a CIA double agent reporting from inside the Kremlin and then spirited out of the country to the US. Short repeats the New York Times for the existence of this agent, but because the newspaper made no mention of the agent’s knowledge of the Litvinenko case, Short claims “others with knowledge of the evidence given in the Litvinenko Inquiry have confirmed that the crucial material indicating Putin’s involvement came from ‘HUMINT’ [Human Intelligence] provided by the United States. The only US intelligence asset in Moscow capable of providing information at that level was the source referred to in the Times account.”

That’s Short’s guess after he has hidden the British sources pointing him away from the MI6 role in the operation before Litvinenko’s fatal tea party. The anonymous New York Times version of the Kremlin source, like the MI6 source who gave me his version of what happened, does not corroborate Short’s conclusion that Putin had instructed the FSB chief, Nikolai Patrushev, to assassinate Litvinenko. “Raw intelligence is not proof”, Short concedes, “but” – note the qualifier removing doubt – “it was prima facie evidence that the decision had been taken by Putin himself.”

This is fabrication by Short once it is understood that MI6, CIA, SVR and other agencies involved in tracking the polonium from Moscow to London interpreted what was going on as an operation aimed at Boris Berezovsky, not Litvinenko. Short’s spies didn’t tell him. He doesn’t know.

Short’s version of the Novichok poisoning case involving Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia has been reproduced directly from the British government’s published stories. “In March 2018 the GRU attempted to assassinate a former double agent, Sergei Skripal, who had been freed as part of a spy exchange and was living in the sleepy cathedral city of Salisbury, in the South of England. The Russian operatives had smeared Novichok, a prohibited chemical warfare agent on the door handle of Skripal’s house. He and his daughter recovered but another person died.”

From his study window in the sleepy village of La Garde Freinet, in the South of France, that’s what Short thought he could see. But he didn’t investigate. Instead, he has concealed that “the sleepy cathedral city of Salisbury” is in fact the centre of British, as well as US chemical warfare manufacture and testing at the Porton Down establishment, and on Salisbury Plain the headquarters of the main artillery, infantry, intelligence and chemical warfare units of the British Army. Short has even muddled the facts of the case, tying the death of Dawn Sturgess to the poisoned door handle. This isn’t simple error on Short’s part – it’s plain BBC standard propaganda. Short claims Putin is guilty again. “In Skripal’s case, unlike that of Litvinenko, there was nothing to suggest that Putin had ordered the attack or even that he approved it…Afterwards, however, he covered up for those responsible.”

Short’s idea of nothing to suggest is plenty. In the case of the death of Sergei Magnitsky, Short cribs Browder’s account without testing the court evidence that Browder is a liar. In his history of the Maidan demonstrations in Kiev in January 2014 and the putsch that followed on February 21, Short repeats claims without an official or intelligence source; he is duplicating the New York Times. Later in the Ukrainian story he reruns, Stepan Bandera “had been rehabilitated…to pretend that the Ukrainian government was run by Nazis was absurd. [Vladimir] Zelensky was a Russian-speaking Jew — hardly the man to lead what Putin termed dismissively ‘a junta of neo-Nazis and drug addicts. For Russians, particularly of the older generation, Putin’s allegations resonated. In the West, they appeared malign and surrwal.”

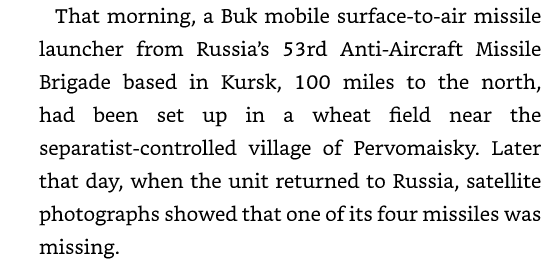

Short has abandoned the truth test. The version he proclaimed at his conclusion — “readers must decide for themselves what is plausible, what sounds false, what rings true and what does not” — he makes impossible because he conceals the evidence, the proof of what could not have happened; in their place he substitutes fabrications. For example, the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine on July 17, 2014, Short reports this way:

This is false. Short footnotes his claims from the NATO propaganda unit known as Bellingcat, but he not only fails to check that source of evidence, he is totally ignorant of the contrary evidence presented during the Dutch court proceedings which began on March 9, 2020. Short doesn’t know there are no satellite photographs of the aircraft incident; that this has been confirmed by the Dutch investigators and judges; and corroborated by Dutch and American intelligence officers whom Short’s interviewees concealed. The photographs Short mentions were fabricated in Kiev by the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU).

For more on the fabrication of the US satellite allegations, click to read.

From MI6, Bellingcat and the SBU, it is a hop, step and a jump for Short to Navalny’s August 2020 collapse in Tomsk. Short repeats the German and other government announcements that “he had been poisoned with a cholinesterase inhibitor, subsequently identified as a nerve agent of the Novichok group, similar to that used against Sergei Skripal in Salisbury.” This account, Short reveals in his footnotes, “is drawn from a Bellingcat investigation”. Short investigated nothing else before concluding that Putin was responsible for ordering Navalny’s assassination.

“The issue, however, was not whether Putin was lying. He was. The question was whether he had himself ordered Navalny killed, or whether…the final decision had been taken by siloviki in his inner circle who assumed that he would be only too glad to see his long-time adversary removed…Yet there are good grounds for thinking that Putin himself took the decision.”

This is Short’s decision — and it’s contradicted by the conclusion he buries at the very end of his book in footnote number 159 on page 757. An incident he reports as striking an experienced CIA agent he interviewed as “inconceivable…was exactly what Putin had done.” Short then pronounces the rule of biographies of Putin and histories of Russia: “the recurrent weakness of Western intelligence services’ and journalists’ reporting on Russian events which do not fit an expected pattern are too readily dismissed as implausible. Anomalies can be revealed and usually merit closer examination.”

Ditto Short.

This new post seems to have resulted in last night’s watercooler vanishing!

I never saw a Watercooler yesterday. I assumed such was the result of American festivities concerning their historical separation from their lawful liege, George III.

Well, Lambert doesn’t post Watercooler on US holidays, of which yesterday was one.

Hmm, smells like straw –> Scarecrow navel gazing

Cut and paste job? Paul Fussell quotes Dr. Johnson as saying an author should be glad of criticism as well as praise because it means his work is attracting notice. Were I Mr. Short, I would wish for a bit less notice.

Amusing was his statement that Russian Studies programs in American and European universities have become “departments of Putin-hating studies.”

And cottage industries throughout the Washington think tanks.

The Guardian had an article with a list of recommended books to get a better picture of what is happening in Ukraine. Every recommendation an atlanticist shill. Absolutely ridiculous propaganda. Incidentally this Short book was given a glowing review, naturally, along with the Belton book that has been successfully sued for libel and had to pulp paperback editions.

‘Short doesn’t know there are no satellite photographs of the aircraft incident’ I am not so sure of that. The US put up a satellite to cover this region the day before and have refused to show anybody any satellite images taken that day. From that I am going to assume that any such image would show exactly where that launcher was and not where people ‘wanted’ it to be.

But one day there will be whole books written about this Putin obsession as it is so widespread in the west. Is it because being intelligent, articulate and competent that he shows up western leaders so much? Leaders like Boris and Biden? At this point I would not be surprised if Christopher Steele came out with a tell-all book soon about Putin and hinting that it was Putin in that hotel room with that pee mattress.

The years’-long anti-Putin hysteria is truly remarkable. The fact that Hillary Clinton chose Putin in 2016, when she wanted a villain to associate with Trump, and that six years later we find ourselves in a proxy war with Russia, on Russia’s border, is amazing. It suggests some long-range planning on someone’s part. All that hate took effort and time to build. Fully realized, it neutralized formerly broad anti-war sentiment among those we used to call liberal Democrats, who now are now mostly as bloodthirsty as the ex-CIA, ex-military on cable.

https://www.marketwatch.com/story/ray-dalio-attacks-u-s-populists-and-warns-russia-may-be-lesser-loser-in-ukraine-war-11656948778?mod=home-page/

The last line is the part of the article that says it all:

“Dalio’s hedge fund in June increased its short bets against European stocks to nearly $9 billion.”

“But it gets even weirder in this case. Author Philip Short was a BBC correspondent many years ago, in Moscow, presumably in the 1970s (he’s not said when). How is it possible for such an individual to get his CIA and MI6 interviews without sponsorship, particularly since some of the CIA and MI6 names do not appear to have been published before? Who is behind his list?”

Sounds like you’re saying such lists are internal documents that can only be used by intelligence employees.

Hint, hint….

“Readers must decide for themselves,” Short concludes his book, “what is plausible, what sounds false, what rings true and what does not…”

That sounds like a disclaimer one hears on gossip sites.

Or this is some kind of “multiple choice'” biography…

A simple search reveals: Philip Short was correspondent from Moscow, Soviet Union, 1974-76 for the BBC.

Talking to Times Radio

The parable of the 3 Blind Men and the elephant is of course well known. . . this article raises the issue of how good is the blind man’s report when he’s never even in the room with the elephant and relies on hearsay from a bunch of other blind men who have never been near the elephant!! Brilliant, & I expect no more nor less from the NGO/Think (sic) Tank world of Western propaganda generation. Bye-bye unipolar world, these idjits can barely dress themselves or function daily I expect.

Tangential, but whenever I hear about the blind men and the elephant, I remember this National Lampoon cartoon . . .

https://www.cartoonstock.com/search?type=images&cartoonist=samgross%2CSam+Gross&page=1&expanded=NL700108

” an elephant is soft and mushy”

That cartoon inspired me to write an extra verse to the classic Victorian-era retelling of that tale –

Six Blind Men & the Elephant

from John Godfrey Saxe (1816-1887)

A Hindu Parable

It was six men of Indostan

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind.

The First approached the Elephant,

And happening to fall

Against his broad and sturdy side,

At once began to bawl:

“God bless me! but the Elephant

Is very like a wall!”

The Second, feeling of the tusk

Cried, “Ho! what have we here,

So very round and smooth and sharp?

To me ‘tis mighty clear

This wonder of an Elephant

Is very like a spear!”

The Third approached the animal,

And happening to take

The squirming trunk within his hands,

Thus boldly up he spake:

“I see,” quoth he, “the Elephant

Is very like a snake!”

The Fourth reached out an eager hand,

And felt about the knee:

“What most this wondrous beast is like

Is mighty plain,” quoth he;

“‘Tis clear enough the Elephant

Is very like a tree!”

The Fifth, who chanced to touch the ear,

Said: “E’en the blindest man

Can tell what this resembles most;

Deny the fact who can,

This marvel of an Elephant

Is very like a fan!”

The Sixth no sooner had begun

About the beast to grope,

Than, seizing on the swinging tail

That fell within his scope.

“I see,” quoth he, “the Elephant

Is very like a rope!”

The Seventh blind man, staff in hand,

Upon his bare feet goes.

“I clearly sense”, he calmly said,

“And think that all should know

The elephant is soft and mushy

In between the toes!”

And so these men of Indostan

Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

And all were in the wrong!

Moral:

So oft in theologic wars,

The disputants, I ween,

Rail on in utter ignorance

Of what each other mean,

And prate about an Elephant

Not one of them has seen.

The creation of Putin as a comic-book super-villain is so typically American. I’m reminded of Tom Wolfe’s take-down in his novel The Right Stuff of the American inferiority complex involving “the Chief Designer (Builder of the Integral!)” and Nikita Khrushchev’s incessant mocking of the U.S. missile program. What do you expect from a culture that learned “history” from fictionalized Hollywood films and TV shows?

Although they lead an economy smaller than that of Texas, Vladimir Putin and Sergei Lavrov are mature professionals of infinite wisdom when compared with the amateur-hour foreign policy clown-car of Joe Biden/Tony Blinken, Boris Johnson/Liz Truss, and Olav Scholz/Annalena Baerbock, who uniformly act as nothing more than puppets enabling war-profiteering by the U.S./NATO Military-Industrial Complex.

When I read braying about the evil schemes of “Putin!” I generally see authors who engage in projection rather than analysis. It’s Russia!Russia!Russia! all over again. Doh! Obama can’t invade Syria! Doh! It got leaked that the DNC fixed the primaries! Doh! Trump is inviting exposure of the hacked contents of Hillary’s illegal Westchester basement server! These writers don’t see the problem as American incompetence, it’s that it has been exposed!

Remind me again why “Ukraine” can’t be a neutral federation like Switzerland?

“Remind me again why “Ukraine” can’t be a neutral federation like Switzerland?”

There’s a joke about Nazis, wars, and finance in there somwhere…

> The creation of Putin as a comic-book super-villain is so typically American.

I mean, f’realz …

There’s a link I keep in my bookmarks as a send-off for brain-addled s***-libs on #Twitter:

Why Putin’s Foes Deplore U.S. Fixation on Election Meddling (via NY Times)

In others words, people in Russia who are opposed to Putin have been screaming since RussiaGate’s inception to please knock it off, because it plays directly to the image of himself that Putin wants to portray – a genius strong-man capable of out-foxing the west at every turn.

Man oh man … #RussiaGate … the gift that keeps

s***tinggiving. Like a surprise puppy you never wanted, given by the aunt (#HRC) you never liked. Dear ${DEITY}, please … free us of this tyranny and allow my mind to live in a world no longer haunted by its specter.Adam Curtis claims that something very similar was done with Gaddafi.

The article is a bit of hilarious-but-maybe-necessary overkill. The stake has long since been driven through the place where Phillip Short’s heart should be. But the hundreds of little details used to nail the coffin shut were fun to read.

One of my favorite activities is reading the morning press and spotting where the junior editors have forgotten the official line and let a contradiction slip through. From Al Jazerra this morning:

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/7/5/ukraine-youngest-mp-sviatoslav-yurash-russia-war

Headline:

“Ukraine’s youngest MP: The world could do much more”

Lead paragraphs:

“Former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych’s Russian-backed government collapsed in 2014 after Ukrainians protested against his decision not to sign a political association and free trade agreement with the European Union.

Sviatoslav Yurash had returned to Ukraine from studying international relations at the University of Calcutta, in India, to join what became known as the Euromaidan revolution. Then just 17 years old, Yurash became head of public relations for the activist group Euromaidan.”

From the interview with the youngest MP in the article:

Al Jazeera: When did you first become politically aware – what was happening around you; what inspired you?

Yurash: While I was studying in India, the revolution was starting in my country in 2013 and it was something I couldn’t miss for the world. My country was going through a tremendous transformation, and I wasn’t going to let anything get in the way of being part of that. I came back for the revolution and that’s the start of when I became politically active.”

So was there a 2013 revolution or were there just 2013-14 demonstrations? Did the government collapse or was it overthrown? Governments collapse routinely in democracies when they loose the majority. But “a collapse” is usually not how we describe the overthrow of a democracy and it’s replacement with a revolutionary regime. Also note that there is no “cause-and-effect” in the whole article, just a time sequence given out of order to confuse the reader. Such tactics work.

The juxtaposition of “Euromaidan revolution” followed by “the activist group Euromaidan.” was also a nice touch.

In fact in 2013 Ukraine’s democratically elected government (a combination of alienated Russian -speakers from the east and anti-corruption Ukrainian speakers from the west) was trying to walk a tightrope and wanted closer links with the EU but also had to find a way to preserve trading links with Russia, its biggest trading partner, which imported the majority of the Ukraine’s iron and steel- which the EU really didn’t want. Both the Ukrainian government and the EU seem to have been bargaining in good faith. But the US would have none of it. So we overthrew the legitimate government and replaced it with Euromaiden. The rest is history.

why not just say he’s Satan and get it done with and save buying and reading almost 700 pages? draw one of those overdone political cartoons and hold it up and point every time you want the general idea conveyed.

i would rather attempt to understand Moby Dick again. and the ~honesty~ would be refreshing.

Patrick Armstrong, a Canadian ‘Russian analyst’ with about 30 years experience with the Departments of National Defence and Foreign Affairs (whatever name it was using at the time) had an interesting blog posting back in 2018 entitled No, Your Intelligence Is Actually Bad. Very Bad where he suggests that US knowledge of the Russian Federation was amazingly bad in the 201x’s. Other posts suggest it has not gotten better since then.

Ukraine can’t be neutral because markets ( Resources).

Neutral on Putin, shorting The Blob and long Entropy.

In general, I’m long Stupid, but I’m shorting The Blob.*

There’s Stupid, and then there’s Just Too Stupid.

NOTE * Not without schadenfreude!

Helmer interjects an interesting digression on Putin as mnemonist. It’s a little unclear from the linked blog post if it’s a natural aptitude that V.V. has, or whether there is some memnotecnic that he acquired.

At university, I encountered a faculty member whose specialty was ancient rhetoric. He claimed that the organization of Aristotle’s Rhetoric was to facilitate memorization, and that in fact Aristotle had a theory of memory. He emphasized the importance of this, and that it was something that could be learned and mastered. I sort of dismissed his claims for Aristotle, as it was never quite clear from the text itself. But that same faculty later appeared on Jeopardy! and became a five-time champion.

If Putin learned some kind of memnotecnic — perhaps during his training in the KGB or later in the study of law —, it would probably be kept secret, and everybody would just say it’s a natural aptitude.

Would not be surprising, as his teacher Plato was big on recollection from whet i can find. Never mind Plato’s teacher, Socrates, that objected to writing things down as it dulled the mind (ironically we only know this because Plato wrote it down, and it was copied and translated across the ages).

From the linked (http://johnhelmer.net/president-putin-makes-a-phenomenal-revelation-in-his-press-conference/) blog post in the article:

‘In “First Person”, the authorized self-portrait prepared for Putin by three Moscow journalists in the year

2000, Putin’s fifth-grade schoolteacher was quoted as remembering “he had a very good memory, a

quick mind”. She didn’t remember him as a prodigy.’

Suggests his “very good memory” was innate, although it may have been enhanced later with mnemonic or other techniques.

The linked post does not suggest Putin “makes stuff up” which he hides in so much data that it is never checked, although it is stated that sometimes “…when in answer to a question, he responds with a set of statistics which, though accurate in themselves, aren’t complete, exposing thereby something more important, sensitive, or secret which he has left out.”

Given that Short’s huge biography of Mao from decades ago is impressively fair about Mao (and a great read–probably my favorite Mao bio), one can only conclude that either his powers have declined, he’s fallen prey to Putin Derangement Syndrome, or he likes lots of butter on his bread. Or all of the above.

There’s very little we don’t know about Putin from the public record.

He has, after all, been a civil servant all his life, and he has spoken often and frankly about himself.

His 30-year marriage ended happily and produced two daughters, one a PhD, MD endocrinologist and the other a professional dancer.

That he is extraordinarily accomplished is indubitable.

Few athletes have held, simultaneously, black belts in three martial arts (all in very tough leagues).

He is trilingual, and professionally trained in evaluating personnel (as his cabinet choices amply prove).

His choice of topic for his PhD means that few people on the planet understand energy as well as he.

He took a country that was on its ass and returned it to great power status–an almost unheard-of accomplishment–while growing the trust of his countrymen to its current 80%.

Anyone wanting to see how he performs under truly dreadful circumstances should watch him address the families of the crew of the Kursk, on the darkest day of the darkest year in postwar Russia. I presume it’s still available on Youtube.

An acquaintance of mine, who sees him weekly, confirms that he is as good off camera as on: a decent man, considerate, funny, and self-deprecating.

Sadly based on a couple of searches, I can find the speech….but only in Russian with no English subtitles. The West apparently does not want non-Russian speakers to form their own views. And there are a lot more vids where the subheads make clear they are depicting the speech as duplicitous.

I was amused by this line:

On the positive side of Short’s character ledger, there are Putin’s self-discipline, loyalty to friends, shyness, loneliness, indifference to money…

Isn’t Putin supposed to have corruptly accrued the greatest fortune in the world of untold billions? That is one of the big western MSM narratives. Including the Guardian reporting on the Panama Papers, where the infamous Luke Harding led with Putin, except he is not mentioned anywhere in those Panama Papers.

Philip Short was interviewed on ‘Today’, BBC Radio 4’s flagship morning news and current affairs program a few days ago. It was only a short interview, but one bit made me choke.

Short opined: “He [Putin] always puts economic consequences in second place. You can se that from the first term, the first five years he was in power when he crushed the oligarchs knowing it was going to be very damaging for western investment in Russia.”

Thank you. That quote says it all.

Please look into Fiona Hill’s new book, “There’s Nothing for You Here” which is fascinating reading IMO. The book’s focus is not Putin’s biography, but he is discussed and analyzed along with DJT. Ms. Hill tells the story of her family’s struggle with poverty in Northeast England as that place de-industrialized, and the relevance of the experience to the global political swing in the past 20 years toward Populism and Authoritaritanism in three countries: England, USA, and Russia. She assessess that Putin is not the primary threat facing the USA as a democracy. We have become our own worst enemy, by failing to address important social problems with solutions.

Don’t know if others above mentioned it, but another piece Helmer links to here, on Putin’s prodigious memory and mastery of key details regarding quite literally any aspect of Russia’s day-to-day operation, is fascinating! Read here. A snippet: