Yves here. This post mentions that the Big Four grain companies use a “just in time system” without explaining how that operates in practice. But they suggest that it is lacking in structural buffers or other protections like being regionally compartmentalized. The US may be hit with diesel shortages in the coming months, which could impede truck and train deliveries. I hope knowledgeable readers can discuss what if any impact that would have on retail food supply in Europe and the US/

By Pat Mooney, an expert on agricultural development expert, a member of the independent International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food) and the co-founder and executive director of the civil society ETC Group. Originally published at openDemocracy

As economies tumble, inflation surges and global food prices soar to critically high levels, two sectors seem to have hit the jackpot in 2022 – energy giants and grain traders.

An estimated 345 million people may now be in acute food insecurity, compared with 135 million before the pandemic. Vulnerable populations face destitution in poorer food-importing countries such as Lebanon, Yemen, Sudan and Somalia. Poor consumers in rich countries are struggling to put food on the table.

Supply shocks caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have been the spark for this inferno of hunger. But the kindling for the fire was already stoked: the severe, underlying weaknesses in our food system.

These include many countries’ heavy reliance on food imports, entrenched production systems, financial speculation, and cycles of poverty and debt. Dysfunctional grain markets and the record bonanza enjoyed by grain traders are symptoms of these flaws.

For decades, four companies dominated the global grain trade and at least 70% of the market. They are collectively known as ABCD (Archer-Daniels-Midland Company, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus). China’s state-owned COFCO and a couple of other contenders in Asia are now joining the ABCD to share in booming profits. Cargill reported a 23% increase in revenues to a record $165bn by mid-2022. And during the second quarter of the year, Archer-Daniels-Midland had its highest profits ever.

As food prices skyrocket and hunger rises, and with the prospect of still more supply shortages, such profiteering is clearly unjust and a sign of abject market failure. The price spikes have happened despite abundant public and private reserves of grain. There is no correlation between the grain traders’ outsize profits and what they are delivering in terms of food security or sustainability. The ABCD have failed to meet their basic functions of ensuring food gets to the people who need it, and does so at a stable price.

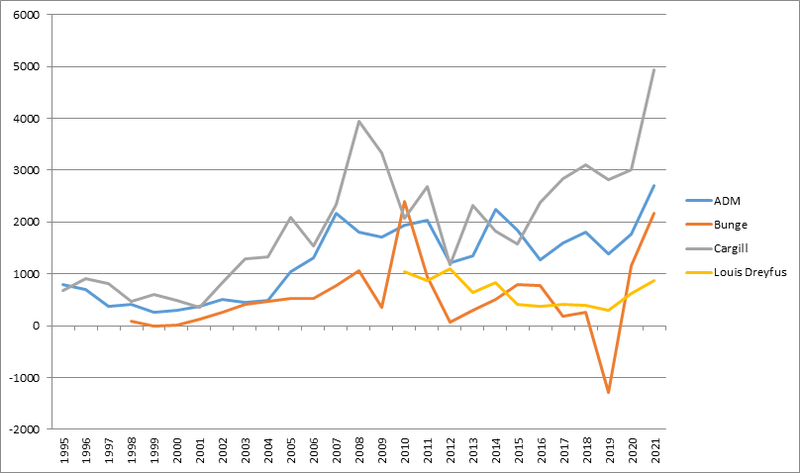

Profits of the big four grain giants 1995-2021

There is a lack of transparency about the ABCDs’ grain stocks. There is also no way to ensure they are released in a timely way. Instead, the grain giants have an incentive to hold stocks back in the hope of higher prices.

But while these companies are posting high profits, others are feeling the effects of the food system they helped design. The globalised, just-in-time food distribution system can quickly be disrupted at a single point. The system is highly specialised, linear and designed to optimise high-volume flows, on the assumption that conditions will be stable. It is efficient for the ABCD to handle just a handful of crops – standardised varieties from specialised production regions that travel along centralised shipping routes. But when the system suffers a shock, it can be shattering. The true test of any system is how it performs under stress and in unexpected conditions. When it comes to securing the world’s food chains, resilience is fundamental – all the more so in a world faced with increasingly extreme weather.

The level of monopoly in the grain markets is also contributing to their failure. The global grain markets are more concentrated than the energy sector and even less transparent. The grain giants wield such influence over markets and government policy development, there are no incentives to change or divest their power. This is a characteristic shared with many other parts of the ‘agrifood’ chain, from seed and agrochemical monopolies to farm machinery and meat production, as documented in a new ETC Group report. And all of them are substantially owned by the same set of asset management firms: State Street, Vanguard and Blackrock.

What Is To Be Done?

A one-off windfall tax on grain giants’ undeserved profits would temporarily help correct the market failure. It would also release billions for food security efforts, mirroring the taxes imposed on fossil fuel giants’ record profits in India, the UK, Germany and soon the EU.

More transparency over grain markets is key. The case has never been stronger for the UN’s agricultural markets information system (AMIS) to incorporate food stocks and trading data from large cereal traders, to reduce speculation and the risk of economic bubbles.

The just-in-time model also needs to be overhauled. Food systems should have spare capacity as a buffer against disruption of production or trade. Toyota pioneered just-in-time manufacturing in the 1960s and it was to be imitated by every other industry. But unlike its rival carmakers, Toyota always made sure its supply chain was diversified and manufacturing hubs localised. Thus, it made itself more shock-proof. For food systems, this would mean back-up networks of regional grain reserves jointly controlled by different governments, and regionalised networks of more diverse foods, crop varieties, seeds, trade routes, companies and producers. Climate change gives added urgency to the task of spreading the risk by prioritising diversity of crops, producers and supply routes.

Ultimately, the ABCDs of this world are the wrong guys to get us out of the multiple crises faced by the food system. The world’s indigenous and small-scale producers have domesticated over 7,000 crops. That’s 6,988 more than are regularly traded by the ABCD. Their crops and non-globalised food webs are the true diversity and resilience we need to supplant our insecure dependency on the ABCD.

I worked in Africa as an engineer for some 18 years and we had a saying for the supply of spare parts:

In stock

Next day delivery

Just too late

Far too late

Death and disaster

Thank you for this very important post. This area of economics is often overlooked because we in the West take available foodstuffs at reasonable prices for granted. (Or we have done until now.)

It’s not only the 4 grain giants but also the big commodity market speculators like Goldman Sachs and others that are “making out like bandits” in this environment. For example, from 2011:

How Goldman Sachs Created the Food Crisis

https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/04/27/how-goldman-sachs-created-the-food-crisis/

Since 2011 GS has cut its commodities investments but the point still holds: It’s not only the Big Ag grain giants causing the problem and profiting. Meanwhile, family farms aren’t seeing any benefit from the price rise since they’re paying much higher prices for inputs.

It’s an old playbook: remove competition and capture the market, create scarcity, raise prices.

Great comment. I’ll read the GS article.

We have been receiving a lesson in just how and for whose benefit monopoly capitalism operates, (see graph of profits above) but I do not yet see a progressive movement like that which cramped the style of the robber barons anywhere on the horizon .

Re: “This post mentions that the Big Four grain companies use a “just in time system” without explaining how that operates in practice. But they suggest that it is lacking in structural buffers or other protections like being regionally compartmentalized.”

On the contrary, the big four are on the “buy” side of the futures market. They buy grain in advance and allow the sellers (farmers) to lock-in a price and avoid the roller-coaster prices. They then take delivery and hold the grain in huge facilities and ship the grain to market. They have capital and the advantages of scale. When they have big losses we ignore it; when they have big gains we read about it in the paper.

If you would like to participate in the price gambling you can via the futures market. This is a risky investment and not for the faint of heart.

yep.

…and like pursuing a civil law suit, the party with the most money generally wins. Or, maybe a bit more like that motivational ‘(/s)’ poster — The race is not always to the swift, but that’s the way the smart money bets.

Sure, anyone can go ahead and play in a rigged game with no inside information. Doesn’t mean the big 4 aren’t in a “heads-I-win, tails-you-lose” position w.r.t. virtually everyone else.

Famine sets the price of grain.

The big grain merchants must maintain a near lock on the permits that allow for ocean shipping, this to allow them to redirect ships bound for one port with a cargo sold at a certain price, to be rerouted to a port where the customer is paying a higher price.

So, say Cargill has a ship loaded with grain in mid-ocean headed for France, and they find a customer in famine-plagued Ethiopia willing to pay more, they reroute the ship bound for France, to Ethiopia, and immediately hire a new ship to take its place to fulfill their French contract.

This would be nearly impossible without their control of shipping permits.

Famine sets the price of grain, and of course the disruptions of war.

Both of which are friends of the grain merchants.

“More transparency over grain markets is key.”

Um, OK, and what will that actually do? Yes, yes, equal information is supposed to enable fair markets, but what if the seller has (bought) all the grain anyway? And what if they buy all the grain-producing land? Knowing how much I am being skint doesn’t help me much, whether I am farmer, shipper, baker/processor, third world government, or just some ‘First World’ schleb trying to buy a loaf of (real) bread that I don’t need to take out a mortgage for.

Ladies and gentlemen, I put it to you: Righting this sort of wrong, equalizing this form of inequity, is the purview and function of government. That is why the governed consent. What government agencies are supposed to do, what the CDC is supposed to do, what the FDA is supposed to to, what the Dept of Ag is supposed to do, what the NLRB is supposed to do, and what the FTC is supposed to do. For us. Our government is supposed to defend the citizens against enemies foreign and domestic.

We have arrived at a place where money is speech, but speech is not speech. I am so glad I am 73, and I weep for the next generations.

Amen. On the other hand, maybe it was always this way … we just don’t see it until we’ve been around the block enough.

structural buffers?

China holds 70% of the world’s animal protein (mostly frozen pork) and 70% of the world’s cereal reserves.

Imagine managing even one of those systems.

Tsk, tsk.

We can’t have banana republics without bananas…

If they grew their own wheat rice etc., we would have to pay far more for the bananas …. We could not sanction them with grain blockades. Wars mean starvation for the civilian population, as the military always feed their ‘men’.

This is the real basis for white privilege:

we can starve ‘them’;

we have starved them;

we shall starve them.

Economics is mostly sophistry and blather designed to ensure that privilege.

The UN may have said something about food as a right …. but who cares?

From a historical perspective Merchants of Grain by Dan Morgan published in 2000 provides good background. Remembering “the Great Grain Robbery” of 1972 is another historical marker https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1973_United_States%E2%80%93Soviet_Union_wheat_deal Adding Glencore who trades other commodities too, Mitsui and Mirabeni both Japanese firms to the ABCD list is also appropriate. COFCO (China), and GASC (Egypt) are state grain traders, mostly buyers. As rice traders, the Japanese Munehisa Homma invented a way to track prices in the 18th century called candlestick analysis still in use by traders today.

Price discovery is crucial and is mostly driven by the Chicago Board of Trade, but also other platforms that are futures discovery mechanisms. Most don’t allow or encourage settlement by physical grain, but it is still done and is the only way grain markets stay honest. Supply and demand without a functioning hedging market is distorted, prices not reflecting value. All these traders make money on volume not by speculating or storing grain although arbitrage is pursued at every chance.

Any effort like the UN AIMS is welcome and necessary and complementary to FAO, USDA, IGC, and others. And no, these companies are not going to lead any necessary changes to food supply but will be necessary to make distributions.

It was Dan Morgan’s Merchants of Grain that taught me the bit of detail I mentioned above.

Dan published that book in 1979 he has an updated book; Out of the Shadows: The New Merchants of Grain published in 2019, I guess things have changed a bit since the first book, but I would guess the bit about shipping has remained important to their profits.

A UN wholesale tax on grain purchases would permit rich countries to subsidize purchases by poor countries, while stabilizing the producer prices at realistic levels, quashing speculation. Rich countries that oppose such regulation should be resoundingly denounced internationally.

This would be enforced by UN control of grain storage and shipping facilities to prevent a black market.

Wheat is both a canary and a black swan. News that the grain corridor out of Ukraine is closed by Russia will limit up wheat. Mexico’s ban on GMO is a way big deal since they’re the biggest customer for US corn. NAFTA ruined Mexico’s centuries old corn growing ways where every small locale had their own landrace corn.