The messy reconfiguration of energy supply chains following Europe’s severance from Russia continues, and it has the West pushing ahead at all costs – even funding much of fighting in a resource-rich region of Mozambique.

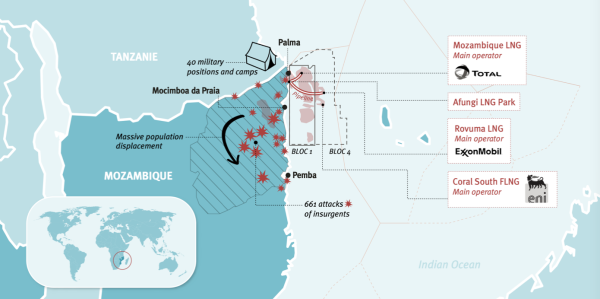

France’s Totalenergies is moving forward with efforts to get a Mozambique LNG project back on track despite serious concerns over violence and human rights abuses in the region. The project was mothballed back in early 2021 due to violence, but is now expected to restart this summer.

Mozambique’s natural gas reserves are the third largest in Africa after Algeria and Nigeria, and if all the deposits are tapped, the country could become one of the world’s ten biggest gas exporters. Much of the reserves were discovered in the Muslim-majority northern province of Cabo Delgado back in 2010.

Massive amounts of money began pouring into the region, the government prioritized the interests of foreign investors, and private security and a local insurgency began fighting. While the conflict in the region is blamed on “terrorists,” the reality is more complicated. From Friends of the Earth:

The Mozambique government is promoting a narrative of ‘foreign Islamic terrorists’ disrupting the LNG projects, but this doesn’t represent the reality of the situation, nor reflect the role that the LNG projects have had in drawing those eager to cash in, and fuelling violence in an impoverished region of a country which is both one of the poorest in the world, and still recovering from a bloody civil war. Since 2017 thousands of civilians have been killed, and almost 700,000 have been forced to flee – being chased from their homes with very few possessions.

Beyond the conflict, 550 families were directly displaced via corporate land grabs, and the blocking of access to fishing grounds, to make way for the infrastructure required for the LNG projects. Promises from the LNG industry of new land and jobs have not been met, and displaced families now struggle to make a living without their traditional livelihoods.

Urgewald e.V.

Thus far, Mozambique and its international backers in the West have failed even to recognise the grievances of the insurgents, which goes far beyond And Responsible Statecraft:

According to displaced Mozambicans, the insurgency today was born out of anger over government corruption, poverty, and poor economic policies. In 2013, three Mozambican state-owned companies secretly borrowed $2 billion from international banks, but the loans were contracted without parliamentary approval plunging the 8th poorest country in the world into a financial crisis yet to be recovered from. This did little to help the 46 percent of Mozambique’s population, especially those in the north, who live below the poverty line.

While Cabo Delgado is resource rich with vast mineral and gas deposits, local Muslim ethnic groups, namely the Mwani and Makua who make up the core of [Ahlu Sunna Wa-Jamo], are excluded from the benefits; including those of French Total’s, a European multinational energy and petroleum company, $20 billion Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) project off the northern coast. The state’s inability to address these social, religious, and political dynamics served as ASWJ’s tipping point into armed action.

TotalEnergies halted its $20 billion LNG project, which is partially financed by the US government, in 2021 due to the violence. In 2020, the US Export-Import Bank approved a $4.7 billion loan for the LNG facility. The Exim statement said that the loan would support 16,700 US jobs and keep China out of the gas field.

Soon after Total was forced to halt the project, French President Emmanuel Macron rushed off to Rwanda, offering the country millions in loans. Macron announced an additional €370 million to finance various development projects in Rwanda. For example, earlier this year the French Development Agency loaned the country 37 million euros in large part to construct a drone operations center.

Shortly after Macron’s visit and his pledging of more money, Rwandan forces were deployed to northern Mozambique in July of 2021.

Through the European Peace Facility mechanism, the EU is funding the deployment of Rwanda Defence Forces in Cabo Delgado in order to fight “terrorism.” Mozambique is also receiving EU funds to secure the area for Total. There are currently around 2,500 Rwandan troops in Cabo Delgado, engaged in joint operations with the Mozambican army.

EU funding of the Rwandan military continues despite the thousands of deaths in Mozambique and displacement of roughly one million people. The Rwandan military also (allegedly) supports militant groups that are constantly pillaging the resource-rich Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The US also supports and trains the Rwandan military as it’s trying to increase control of resources in the region and box out China.

Much the same way the US uses Rwanda for proxy forces in the DRC, the EU is using Rwandan forces in Mozambique. And so with the financial support of the EU and help from Rwanda, Mozambique has been able to quell much of the insurgency in Cabo Delgado through massive displacement, but sporadic violence continues.

As Total faced problems getting its LNG operation up and running, the description of the insurgency changed from a battle over economic grievances to one of international Islamic terrorism. The US entered the fray, sending Green Berets to Mozambique to “prevent the spread of terrorism and violent extremism.” It also conveniently provided a cover for the US and France, who have important economic interests in Cabo Delgado and want to keep Russia and China out of the region.

Beijing has a longstanding relationship with Maputo, the Mozambican capital, which features a recently refurbished airport and Africa’s longest suspension bridge, both courtesy of Chinese companies. China is also Mozambique’s third-largest source of imports and second largest export destination.

Last year the Chinese National Offshore Oil Company was awarded five exploration blocks in the most recent Mozambique licensing round. The China National Petroleum Corporation has 20 percent of area 4 off the coast of Cabo Delgado, where LNG shipments from a floating platform began late last year. The two main owners of area 4 are the Italian energy company Eni and ExxonMobil with 25 percent each.

Mozambique is important source of timber, titanium, sand processing as well as other resources, for China. Beijing also uses Mozambique as an entry-exit point for landlocked and resource countries Zimbabwe and Zambia.

China has also been increasing its footprint in Mozambique by buying stakes in Portuguese companies. From Dr Joseph Hanlon, a visiting Senior Research Fellow in the Department of International Development at the London School of Economics who has been writing about Mozambique for 40 years:

China has become the fourth largest foreign investor in Portugal. The state-owned China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) recently took a controlling interest in Mota-Engel, the largest Portuguese construction company which also is largest in Mozambique. It is involved in construction relating to the Cabo Delgado LNG production facility, mining, and Maputo apartment blocks. Most recently it has been involved in constructing wharf and unloading facilities in Palma and Afungi.

The Fosum group is the biggest shareholder in Portugal’s largest bank, Millennium bcp, with 29.95%; Millennium bcp owns 66.7% of Millennium bim, the largest bank in Mozambique. China Three Gorges (CTG) is the largest shareholder in EDP Energias de Portugal with 20.22%. EDP is a leader in renewable energy and has projects in Mozambique.

Mozambican government officials regularly praise Chinese aid and investment, as Beijing is the country’s largest bilateral creditor at $2.2 billion. Every president since Mozambican independence in 1975 has made multiple trips to China, and it has also hosted every Chinese president and almost every premier for official state visits over the same time period.

***

Beyond the natural gas, the US is also interested in using Mozambique to bypass China in the control of critical minerals, in this case graphite, for the green energy transition.

Mozambique was one of five African countries invited to the US Minerals Security Partnership on the sidelines of last year’s UN General Assembly. At the meeting Secretary of State Anthony Blinken mentioned the importance of a mine in Cabo Delgado from which graphite will be sent to Louisiana for processing. More from allAfrica:

The US Department of Energy (DoE) in an 18 April statement said “today the United States is 100% reliant on imported graphite as China produces nearly all of the high-purity graphite needed to make lithium-ion batteries.”

The DoE is providing $107 mn loan to the Australian owners of Balama, Syrah Resources, to build a processing factory in Vidalia, Louisiana, to produce graphite-based anodes for lithium-ion batteries. The DoE said the plant would create “98 good-paying, highly skilled operations jobs within the clean energy sector.”

Yet again, Mozambique gets nothing but a hole in the ground, while the manufacturing is in the US.

***

The Total LNG project is now set to be restarted in July. The company’s chief executive Patrick Pouyanne took a road trip around Cabo Delgado province last month, and said the security situation has improved “significantly” since Total had to close up shop in 2021. Pouyanne also commissioned an “independent fact-finding mission” to assess the human rights situation, which will presumably give the green light for work to resume.

It will be the first onshore LNG plant in Mozambique. In November, the first LNG exports from the area left Mozambique for Europe, but it was produced at Coral Sul, a floating facility managed by the Italian company Eni.

The Total project off the northern coast contains approximately 65 trillion cubic feet of recoverable natural gas, and the company plans to expand up to 43 million tonnes per year. According to the International Gas Union’s World LNG Report, Mozambique will be one of the biggest beneficiaries from additional LNG capacity between 2022-2026 after Russia (although the status of upcoming projects is uncertain amid the Ukraine conflict), Qatar, and the US.

Eni, the major Italian energy company, shipped its first cargo from the Coral South field in November. Eni has said Coral-Sul is the first of three FLNG projects planned in Mozambique.

Eni was still receiving around 80 percent of its supply from Russia before the EU ended that arrangement last year. The company is now planning on receiving zero Russian gas moving forward and is aiming to replace 80 percent of the gas it received from Russia before next winter.

Of course it is having to spend a lot more in order to accomplish that. From Natural Gas Intelligence:

Eni is aiming to fully replace the gas it previously received from Russia with 20 billion cubic meters (Bcm) of additional annual supply from imports and equity production projects by 2025. It assumes 9 Bcm will be supplied by pipeline and 11 Bcm will come from growing its integrated LNG portfolio.

Eni upgraded its guidance for capital expenditures over the next four years by 15%. It now expects to spend around $39 billion as it seeks to progress production and energy transition projects.

Even if US and EU backing help Rwandan and Mozambican forces completely clear Cabo Delgado so the LNG projects can hum along uninterrupted, it will still be a drop in the bucket of the effort to replace Russian gas. According to GIS, the entire African continent’s proven gas reserves are equivalent to 34 percent of Russian resources. In 2020, total gas trade between Europe and Russia was nearly 185 bcm. Mozambique might be able to hit 14 bcm by 2025 if everything breaks right.

Nearly five years after his arrest at the OR Tambo International Airport here in Johannesburg, the former Mozambican finance minister who signed off on the $2bn loans scheme continues to be confined to a jail cell not far from where i’m typing this, and is the subject of a bitter extradition tug of war between the Americans and Mozambique. As regards the situation on the ground in Cabo Delgado, the west is clearly salivating at the prospect of tapping this new extraction frontier to accelerate its decoupling from Russian energy supplies, and as always, chaos, destruction and terror are certain to ensue, as they have in other resource rich regions were the western fossil fuel majors set up camp to “partner” with local governments and their corrupt elites. As the article rightly highlights, the “Islamic terrorism” motif that gets liberally sprinkled on any coverage of Cabo Delgado conveniently oversimplifies a complex issue that would benefit from a thorough analysis of the root causes of the insurgency in the region, including the role of colonial developmental neglect and post independence corruption and non-responsiveness to the needs of the people in the North of the country by (furthering the neglect by the Portuguese colonial masters) by the political elites concentrated in the south of the country in Maputo. But as we know, the role of the media is to provide cover stories and the “security situation” myopia is one such tactic, the other being creating urgency around the need to tap the resource wealth of the region to “benefit local communities” when in reality said communities will see very little of the wealth created from exporting the gas trickling down to them (and the transfer pricing magic dust will be sprinkled on whatever taxes would naturally accrue to the Mozambican government, making them disappear). With the Ukraine war being a forcing function for western countries to desperately scour the globe in search of new energy extraction frontiers, and the stated intention to “counter Russian and Chinese influence” on the continent, countries like Mozambique are about to be hives of western sponsored (subversive) activities.

Couple of points. The rise of Islamic terrorism in the region is a well-known story that has been extensively documented for at least the last 5-6 years. It’s partly the Islamic State and partly another group, Ahlu Sunnah Wal Jama’ah, which is nastier than the IS, although not, apparently, totally distinct from it. Foreign fighters, as elsewhere in Africa, seem to be swelling their ranks.

Here’s a recent report from a respected African think-tank which sets out the situation is some detail, and is written by people from the region who are, let’s say, somewhat better informed than Friends of the Earth. As the report says, there’s a tendency to see these crises through the traditional western development NGO prism of “historic disenfranchisement, poverty, marginalisation, endemic corruption and political exclusion.” But it’s a lot more complicated than that, and includes a lot of regional disparities, as well as unsettled business from the FRELIMO war. As a general rule, it’s hard for western commentators and NGOs to understand that these some of conflicts are, at least to a degree, religious in nature, and, certainly in the case of ASWJ, do not seem to be popular movements (indeed, they prey on the populations.) The situation has stabilised a bit with the deployment of not only Rwandan forces but also a contingent from SADC.

There’s nothing “alleged” by the way about the pillaging of the DRC by Rwanda. It’s been going on for twenty-five years (in company with Uganda for some of that time) and is an international scandal that the regime in Kigali has so far managed to convince the West to ignore. On the other hand, the Rwandans have probably the most ruthlessly effective military in Africa, and if I were the ASWJ, I’d be frightened of them. That said, Macron’s initiatives with Rwanda have nothing to do with Mozambique. Being of a younger generation, he’s made it one of his Presidency’s objectives to “repair” relations with Rwanda, by making concessions and providing money. But Kagame is only interested in manipulating donors, and the long-term policy in Rwanda (as you can see from the renamed streets in Kigali for example) is to destroy all trace of the French (actually Belgian) heritage and move the country firmly into the US camp. So long as Kagame’s bloody regime is in power that will continue. It’s not surprising that I’ve heard the Congolese, for example, refer to the Rwandans as “American mercenaries.”

A cursory glance at the list of ISS donors leaves one hardly convinced of the impartiality of its research output, so, as someone very familiar with what they do, i naturally dispute the notion that it is a “respected” think tank guided solely by the need to put empirical rigour stripped of political/ideological considerations at the centre of their work. While I’m not above giving them praise when it’s due, I do find that their various articulations of security situations in Africa tend to want to bury western culpability in talk about “complexity”, which is a well worn tactic often used to shield certain actors from accountability. The situation in Mozambique is indeed complicated, extremely so, and some of the things you mention do account for the challenges we are seeing on the ground, but they’re no more important in my view than the economic disenfranchisement and political neglect of the population in the north, because poverty tends to be the match that lights the fuse of tribal/religious/ethnic tensions (and said poverty is directly traceable to political corruption, developmental under-investment, and in resource rich countries, the unfettered plunder by rapacious western fossil fuel majors).

I know the organisation concerned well (or I did, anyway) and I also felt over the years that they were too influenced not just by donors, but by a particular category of donor: stable, liberal, secular, small countries with big ambitions. This, of course, is a pervasive problem in Africa, where all the research institutes I know of are directly or indirectly donor funded.

The point I was making is not to minimise the importance of the economic factors you mention, but rather to regret the fact that there is too little serious analysis of the religious dimension in conflicts in Africa, and in particular the question of Political Islam. This is a pervasive problem with conflict studies in recent years: donors like the Canadians, the Swedes, or the EU react badly to the idea that some conflicts are in part genuinely religious in nature, because it’s an idea which is completely foreign to their way of thinking. They just want reports that talk about the famous “underlying causes.” (The same problem exists for studies carried out in the Middle East.) I think there’s also a very important difference between poverty igniting dormant ethnic and religious tensions, which obviously happens a lot, and actual examples of holy war, which is a different thing, and where the Muslim populations are often the first victims

For what it’s worth there’s now a mass of studies on ISIS recruitment in Europe, and it’s striking that a lot of recruits come from comfortable backgrounds and can be quite highly educated. A surprising number are converts. For many, they have found a cause and something to live for in a society which offers them nothing else of any interest. The kind of social, economic and political failure that we see in Mozambique may fulfil a similar role, even if the process is not a mechanistic one.

>>>For what it’s worth there’s now a mass of studies on ISIS recruitment in Europe, and it’s striking that a lot of recruits come from comfortable backgrounds and can be quite highly educated. A surprising number are converts. For many, they have found a cause and something to live for in a society which offers them nothing else of any interest.

This likely has more to do with the increasingly empty emotional, spiritual, and philosophical emptiness of modern society. When money is what it is about and most religious organizations like the Catholic Church have serious problems that the leadership refuses to deal with, and many of the other social institutions that offered connections in the past especially in the United States have been destroyed as well, people are going to be looking for something, anything, to fill the emptiness. Cults and some of the more extreme cult like elements of even regular religions will attract people.

It is the whole enlightenment idea of separation of church and “state” that comes to play, because it basically dismiss the overlap between religion and culture.

Even USA, who is supposedly the poster boy for such a separation, is culturally colored by the puritan roots of the original English colonies (never mind that USA seems to be the place where obsolete practices get a second life).

Thanks for your input and is there any sites you might want to share that are more to telling the truth?

Thanks jo6pac, given the heavy influence donors exert over research output (as David says above) there’s honestly a dearth of resources one can recommend that put out work that’s not designed to confirm the priors of said donors. Publications like newafricandotcom, although more news focused, tend to do a better job than the various NGOs and think tanks out there.

Yeah as i have come to understand it, the whole DRC mess is a regional resource proxy war between USA and France. Not sure when and where i picked up the idea though.

France really is an enigma in international politics, as it is very sensitive about threats to anything “french”.

” …. 550 families were directly displaced via corporate land grabs, and the blocking of access to fishing grounds, to make way for the infrastructure required for the LNG projects. Promises from the LNG industry of new land and jobs have not been met, and displaced families now struggle to make a living without their traditional livelihoods.”

More of the “they’re a bunch of poor, uncivilized Blacks (Redskins, Orientals) who are not maximizing the profitability potentials that can be extracted from these lands. So they don’t deserve to live here,” mindset that has led to this crisis that faces humanity on our warming and polluted planet.

Thank you, Connor, for your writings that explain the sordid backstories going on in these African nations that most of us in the US don’t even know exist. They are not easy reading, but necessary.

John Michael Greer’s novel The Twilight’s Last Gleaming starts off with an oil discovery in Tanzania, which the Tanzanian government has the temerity to allow the Chinese to develop. Hmmm….. Tanzania is just north of Mozambique.

(Spoiler: it doesn’t end well for the aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan)

For what it’s worth, this South African has always assumed that the main object of setting up a guerrilla force in northern Mozambique was to disrupt the French gas operations there. If so, the most likely suspects would be the United States and Qatar, both of which have a long history of supporting Islamic extremism in the hope of making commercial gains out of it, and the U.S. has a history of disrupting other peoples’ gas exploitation so as to seize it for themselves.

Of course there are completely legitimate grievances in Cabo Delgado, much as there were completely legitimate grievances in central Mozambique when the MNR were murdering, raping and looting there with South African and American backing. That doesn’t mean that the guerrillas have any intention of ameliorating those grievances.

The Institute for Security Studies was once described to me by a well-informed academic as a relief agency for superannuated apartheid-era spooks. Of course some of those spooks were not idiots, and in the immediate post-apartheid era it made some valid points. But by now, like Solidarity and the Institute of Race Relations, it’s little more than a mouthpiece of corporate propaganda.