Yves here. Richard Murphy presents a provocative analysis on the role of interest rates in inflation. I’m not convinced, since I assume most businesses try to have a fair bit of longer-maturity debt, and would thus only be partly exposed to central bank interest rate increases. Where those will bite first is for funding new projects, since most investors like to use at least some borrowed money.

Perhaps the better question is in what sectors is Murphy’s analysis most likely to apply, as in which companies (ex financial services companies) borrow mainly short term or at floating rates?

By Richard Murphy, a chartered accountant and a political economist. He has been described by the Guardian newspaper as an “anti-poverty campaigner and tax expert”. He is Professor of Practice in International Political Economy at City University, London and Director of Tax Research UK. He is a non-executive director of Cambridge Econometrics. He is a member of the Progressive Economy Forum. Originally published at Tax Research UK

I have been suggesting that interest rate rises are fueling inflation.

That idea might, it seems, shock the Bank of England. They seem to think that inflation is down to excessive pay increases. However, I have some news for them, which is that employees do not set price increases. It is companies that do that. In that case, let me put forward a model of a company that is largely service-based to explore my suggestion.

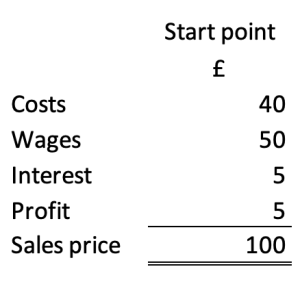

This is the starting point for this model:

The figures have been chosen for purely representational purposes: they are denominated in monetary units (thousands, tens of thousands, or millions: it makes no difference) but also, in effect, indicate the percentage split in the cost base of the company. The proportion of wages suggests it is service orientated, as most companies are.

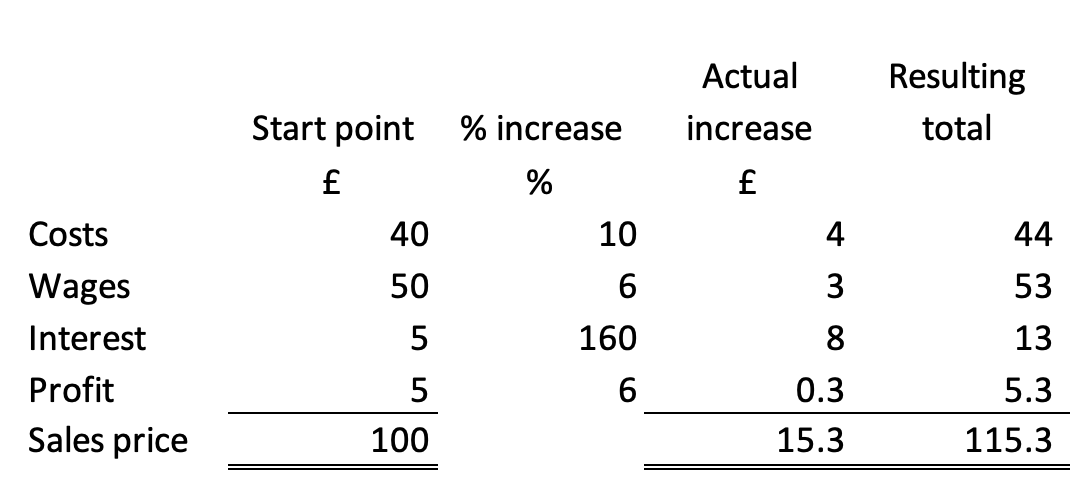

Then I suggest that adjustments for inflation be taken into account, as follows:

Bought-in costs have increased by 10% – roughly the rate of inflation in the last year.

Wage increases have been kept to 6% – which will be tough on many staff.

The big increase is, however, in interest costs. The company pays interest at 3% over bank base rate. So, the rate has grown from near enough 3% to 8%, or a growth of about 160%.

In comparison, profits have only been targeted to increase at the same rate as wages.

The resulting overall cost increase is 15.3%, with more than half of that being due to interest, which imposes a bigger cost increase than external costs and the wage settlement combined.

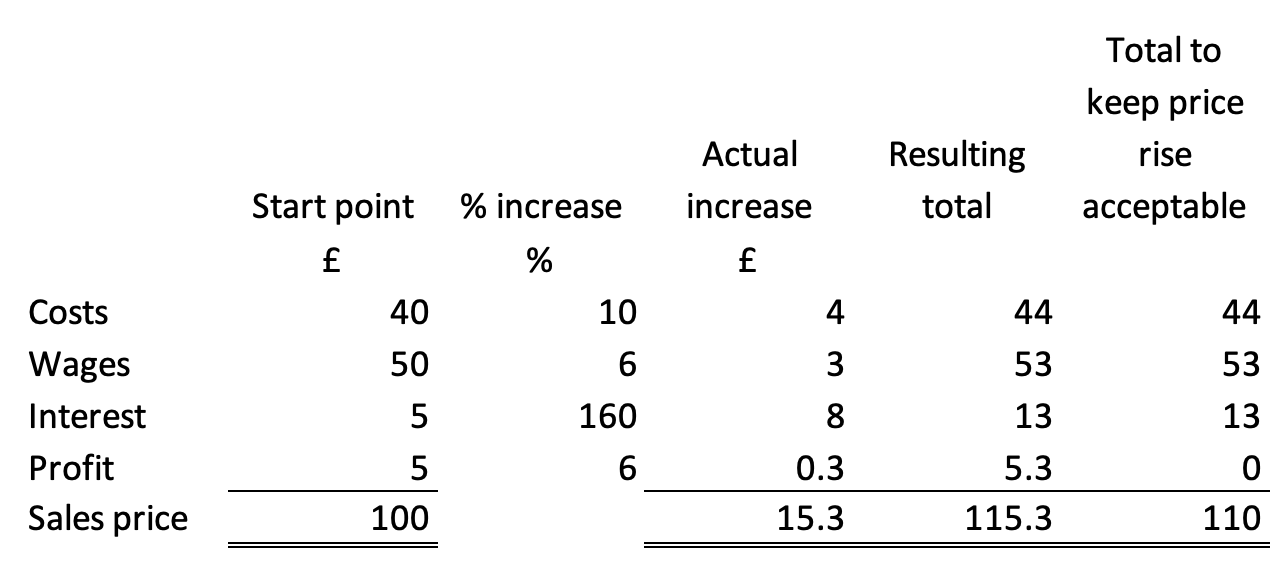

Let’s presume the company realises that the market will not accept a 15.3% price increase, and it keeps it to 10%. This is the result:

Profits have now been eliminated. The company’s future is, then, in doubt.

I stress that this is a model.

I would add that the assumptions seem fair, as does the cost structure, although these (of course) vary widely.

My points are threefold. First, it is not wages that are driving up inflation.

Second, it is interest rate rises that are driving up prices.

And third, interest rate rises are now so extreme that many businesses will face the threat of failure.

The Bank of England is welcome to use this model and think about the consequences which they have created. Unfortunately, I suspect that they will not. That’s because what this model makes clear is that we face a crisis created in Threadneedle Street, but they have no understanding of what they have done and are doing.

And that’s why we face desperate economic times.

I don’t trust myself to analyze Murphy’s model, but I do know that Mosler has been arguing that the rate increases are contributing to inflation via the interest income channel and that at current US Federal debt levels interest payments represent a fiscal stimulus in the order of 8% of GDP.

Of course that fiscal stimulus is of the most regressive sort imaginable, distributed as it is to those who already have money (in the form of T-bill and bond holders).

I came across Mosler’s argument several years ago and I tend to agree. The neo-liberal economists tend to ignore borrowing and credit except for their models that tell them higher interest rates lower demand through lower credit. However, they tend to ignore the fact that interest expense for entity is income for another. Therefore, if the additional income generated by interest is more than the reduction in credit demand you are going to get a net infusion of money, since one of (if not the) largest payers of interest is the US govt. This interest seems to me to be highly inflationary, as it is just injecting money into the system without any actual goods or services being produced (MV= PQ).

Also, I’ve tried to make Murphy’s exact point on this very site before (a few times), but didn’t get any feedback, so I’m glad that it’s finally getting some attention. Interest expense is a real cost to many companies. Not just in the service sector as in Murphy’s example, but also in retail and construction, most input goods are bought on credit terms. The increased cost of credit is then passed on to consumers as higher prices.

The question then becomes how do these various impacts of interest rates interact with each other to produce a net result of higher or lower prices.

Forgive the terrible name-dropping, but I was speaking to Mr. Mosler last night and he reiterated this message. What do you think will happen if you run an 8% of GDP fiscal deficit of which interest as an expense in the budget is set to amount to 5% of GDP cos debt to GDP is approx. 100%? And bear in mind this is a low estimate of the transfer payments implied by 5% rates with debt/GDP levels.

Mr. Murphy’s model addresses a cost push. I noticed a piece by Servas Storm which seemed to encompass Mr. Murphy’s observation. Mr. Mosler’s observation is directed at a demand pull. A massively regressive, with powerful distributive effects flow of funds boost to the private sector. And where will this madness end? Unclear. Imagine trying to slow the economy by only addressing that part of it which is exposed to higher debt service costs while running an 8% of GDP deficit?

Profit Inflation Is Real By Servaas Storm

Prices can only increase if the money supply increases. Companies do not create money. They set prices. If customers want to pay the (higher) price then prices go up. And volumes sold go down unless money supply in the entire economy increases, or Banks create more money via Fractional Reserves.

U.S. inflation is Government spending, to reward their supporters.

For one, prices can go up without an increase in the money supply if the velocity of money increases. For another banks to not create money via fractional reserves. The reality is that bank lending is demand based. Banks simply expand their balance sheets for extending credit. If required they borrow it from another bank or the central bank. Lending standards and capital requirements are what restrains lending, not the amount of deposits.

This is a myth that goes back to the textbooks which is even repeated by Nobel prize winners.

Don’t lenders virtually “print money” when they extend credit? That is, an unbacked IOU value is entered as an asset. The lenders total assets, their combination of reserves and IOUs, look like all real value. To the extent that some loans, aka IOUs, were risk-heavy to start with, the day comes when the “too big to fail” lender will come with hat in hand and ask for a bailout.

Those who believed in the wage-price spiral explanation are now the folks who take for granted that debt-based capitalism is god’s plan.

The rookie has to look for an angel or venture capitalist, but is not eligible to go directly to unbacked loans. But the established entrepreneur has even trained the public to think that eminent domain to collect better taxes is his/her actual constitutional right from the takings clause “for public use.” The assumptions of modern economics would have the public think that “just compensation” is the same as “fair market value” [cheap] without accounting for the loser’s fees for moving, settling, finding new customers etc.

Let’s acknowledge that the distribution of price increases and the distribution of income both matter a great deal to your viewpoint, for you’re talking overall across the board increases. In reality, price increases for necessitous spending can increase well beyond money supply increases even in the long run. My view is simply that money supply changes do not govern the distribution of price changes in most economies.

Banks are companies, and they do create money. But the broader point is its quite difficult to have an 8% of GDP fiscal deficit, and not create quite a lot of new money. You would need to be doing some quite extraordinary things in monetary policy to offset it.

I am also skeptical.

If I recall, inflation came first, not interest rate rises. One could argue rates are still historically low, and were raised from years of near zero. On the surface, a few points of rate rises cannot account for the double-digit inflation or near double-digit. Of course, we are talking about consumer price inflation, not asset price inflation.

Didn’t Powell even say that rate rises were meant to push down real-term wages? (Inflation rates already outpace wage rises, thus labor is taking a real-term cut)

Besides, I thought we had seen from a previous study that most inflation was from price-gouging (monopoly rent, “windfall profits”, unearned income). BigOil posted record “profits”. Energy price rises started a domino effect of inflation and provided a great excuse for oligopolies to jack up prices as well.

Profs Radhika Desai and Michael Hudson, did a segment on inflation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZhZbB0jjDTM

Totally right on with the observation of price gouging and wage depression.

Now, corporations are going after retirements whose cost was kicked down the road until FAS 106 made them appear on the balance sheet.

As best i recall, this inflation comes from a lack of supply rather than an abundance of demand. End result is that adjusting interest rates, the cost of introducing new money from lending, will do very little. If anything it could make the situation worse, as it will hinder the ability to expand supply routes etc from lack of cash.

That’s partly an issue of interest rates impacting investment, but the bigger problem has been the game financialization, which not only hinders introduction of new capacity, but ala Bain Capital, makes wrecking existing capacity in order to strip out the wealth a profitable enterprise for the 0.01%

Yes!

Yes, 1) wrecking capacity:

Carl Icahn sold off Pan Am’s best routes while the company was off the market, and he pocketed the profit.

and 2) strip out wealth:

Icahn then put Pan Am back on the market and sold all his shares. The company is gone.

My Aunt worked for Pan Am in Asia, back when they had the US based airline monopoly on overseas air-travel. Fortunately she died happy and content before Icahn got his hands on the pension funds. Having said that, airlines are a bit unique, in most cases the airplanes don’t go away, the airports don’t go away, routes, the gates, etc. What goes away is mostly pension funds and union contracts, everything else winds up in new livery to start the whole rip off over again. Factories & plant are a different matter, it’s seldom that equipment itself is ripped up and moved, in many cases it’s not even ripped up and scrapped, but the whole facility is left to rot away until a superfund comes in to clean up.

By his logic, of course, interest rates should be reduced to -5%, company’s costs will fall and in the competitive market they will pass these savings onto consumers through lower prices.

I wonder if he knows why that would be crazy?

hint: (1) businesses are not the only financial actors (2) generalised price increases are a function of money, not of business costs)

Wondering what refurbishing and recycling would do to the cost part of the equation. RM is accurately targeting the cause of inflation (it is not labor) so that leaves profit, logically. And if we stopped our planned obsolescence economy and began to account for the massive waste it entails, costs would at least shift around and probably go up until an equilibrium was established that might logically keep inflation from happening at the benefit of profiteers and the detriment of economies/societies/environments.

how about this alternative spin: until this quarter central bank interest rates were still negative in real terms versus inflation (whether measured via headline inflation or “sticky-core” inflation).

Even 1.5 years of rapid rate hikes can’t immediately undo nearly 20 years of negative real rates.

Isnt that the whole point? When businesses are shuttering and laying off people, those people lose their paychecks (or are forced to take home less pay if they continue working). That means less demand/consumption in the overall economy. Standard demand/supply graph shows that when there is less demand price goes down.

Murphy brings up an interesting point–inflation may increase a bit temporarily as some businesses do everything they can gasping for one last breath of air, but I dont think thats relevent to where we end up. We could even be past that point already

All of the major grocery distributors (all 3? or 4?) rely on fairly shady financing to float restaurants and grocery stores. I wouldn’t be surprised if that didn’t affect food prices. At any rate any JIT retail distribution channel has to using short term credit at some point along the chain as source price increases happen on a near weekly basis while existing contracts guarantee delivery at an earlier set price. That’s going to amplify inflation as high interest debt payments factor into price increases.

I also tend towards your argument. There are sectors that rely upon short-term credit to fund rolling capital — food distribution is one, food transformation (where acquisition of raw material is seasonal or costs vary a lot from one year to another, and selling of finished produce can also be very seasonal, hence stock build-up) is another.

I however doubt that the service sector in general is impacted by the interest-rates variations that Murphy describes — at least not to such a meaningful extent.

I agree with you about the service sector in general, save for banking, finance and real estate.

The higher debt levels, the truer is the model. I suppose

Something every liberal economist seems to ignore is that inflation is an emerging property of a complex system; many factors figure into it, both positively and negatively. So while some inflations may be caused by excess money, many others are not. Similarly, some inflations can be reduced by raising interest rates, others cannot.

Indeed, in some cases, raising interest rates can cause an increase in inflation, as Mr. Murphy’s model suggests. Whether this is actually the case in the UK or not, is hard to tell without looking at data.

As the saying goes. “To a man with a hammer….”

I like your way of thinking that there are different types of inflation, e.g. food inflation, wage inflation.

However there is only one “generalised price increase” inflation and that is the only inflation central bankers should be concerned about, and also the one that is a function of the money supply.

Again, even this one “generalised price increase” inflation may have a multitude of causes. For example, during the pandemic lockdowns, supply chains were disrupted worldwide, generating just such a “generalised price increase”. The cause was not an excess of money, but a shortage of supply. That is, nothing to do with interest rates.

Now, a “clever” liberal economist would say excess money supply and scarcity of commodity supply (conversely, excess demand) are the same, since these are relative to each other. But that’s *stupid* because many demands in the real world are independent of money supply (e.g. food, housing, healthcare, transportation, …).

You are right that shortage of supply has the same effect as increase of money. The classic example is the rise in labor costs after the Black Death.

It is the central bankers who have signaled that they will keep the value of money approximately constant regardless of whether they have to fight money creation or reduction in supply. They do this for good reason: if you clean my house for $x this year, you should be able to pay me to clean your house next year for approximately $x. This is a good thing as it helps us plan our lives and people won’t work for money that will have no value in the future.

Many demands are inelastic, but none are independent of real price. People do eat cheaper/less, do move to smaller homes, don’t go to the doctor, drive less or take the bus when money is tight.

We would all like our basic needs to be independent of our incomes, but sadly that is not the case.

In the next 25 years we may see the situation in the world where, because of climate change and further population growth, there is crop failure and literally not enough food in the world for everyone. In this situation the world economy would be so far from an equilibrium that central bankers will be powerless to protect the price level. Luckily we are nowhere near that place yet!!!

An interesting example is Brazil in recent years: They have a crazy high interest rate (13.75%), and still face inflation. What caused the inflation?

Well, the government had established a price policy for the state oil company Petrobras, in which it had to sell its locally produced fuel products at the international market rate – including all costs associated with importing the same fuel from overseas. Since in Brazil everything moves on trucks, the resulting significant increase in fuel costs pushed up the prices for everything else. Voila! A generalised price increase caused by bad (neoliberal) policy, completely immune to interest rate hikes.

Absolutely!

Given the amount of US companies sponsored by one PE firm or another – who heavily saddle said companies with floating rate debt – I find the model sufficient. Leveraged loan balance has swelled to over $1.5 trillion.

No company or sponsor will accept $0 profits. I suspect they will find a way to lower wages to fix that.

Here is an interesting discussion of the standard macro IS/LM model…for what it is worth.

https://globalmacromatters.wordpress.com/2013/04/06/disequilibrium-economics-the-islm-model/

This model and its variants evolved out of a period when a primary presumption was that labor (meaning union labor) was highly responsible for cost-push inflation. I remember when Mike Quill of the Transit Union stood up to the ruling class in the 60s demanded raises for the workers. It really was a hell of a row. Be nice to have him around now. The first time I ever heard that an increase wages could cause inflation. Anyway, they never seem to have gotten around to modifying the model for an economy dominated by imperfect competition.

My personal viewpoint: first show me the empirically observed IS-LM curve, based on national statistics, for the economy under discussion (USA, UK, Germany…) — not the abstract diagrams without scales and no relation to actual economic data so much loved by economists — and then, and only then, I will start viewing that “model” as worthy of further consideration.

Well exactly. IS-LM is a tool for explaining a deficient model to students. Nothing else.

Yup.

The next time I see all lakes, seas and oceans in ‘perfect equilibrium, without a single wave to mar their glassy surfaces, I’ll have complete faith in IS-LM ‘explanations’.

It is an empirical question. Capital intensive companies tend to term out their debt and rely on fixed rate financing. Thew will roll over their debt over a decade or so.

Meanwhile Consumer packaged goods firms don’t have much debt.

Retailers do everything to manage down their cash conversion cycle. For Krogers, it is 10 days. The ccc is inventory + payables – receivables.

So, I agree with Yves…”I’m not convinced, since I assume most businesses try to have a fair bit of longer-maturity debt, and would thus only be partly exposed to central bank interest rate increases.” but will add that it is empirical, so a convincing argument needs more than hypothetical financials.

This makes me wonder of Erdogan has not inutitively grasped some aspects of the relationship between interest rates and inflation. Unless Murphy, he probably cannot articulate his intuition well.

As I have been saying since the 1980s, moving money into real estate is a bas idea. When real estate costs 20% of income in 1980, compared to the 50% now, this means that when there is an increase in interest rates, the costs to businesses and the individual are more than double what they used to be. On top of this, the value of labor has decreased because labor is less of a factor in most manufacturing. In 1980, labour would be around 30 to 40% of product costs, now it is often as low as 10%, with the bulk of the rest being bought materials (which often are bought on credit to cover the time factor of manufacturing).

If you want to cut inflation, cut real estate costs. Increasing interest rates only increases bank profits (the debt servicing costs increase as interest rates rise). If you halve the value of property, this releasees capital for other uses and deters investment in real estate, forcing the finance market to move it capital into other sectors – transport, manufacturing, R&D, etc. which is what they used to do before 1980, when the neoliberals rigged the markets so that quick returns of bricks became more profitable then investing in ideas and the future

Is a rent a cost? If we define it classically then it isnt. Meaning that those rents just wont get paid and the price of real estate will just come down if rates go up….

Our problem with rents is that we destroyed Pension Culture, and so people latched onto real estate as a substitute pension.

We have found ourselves in the same predicament that British industry faced in the 1800s: parasitic landlords overcharged workers on rent and food, which made workers more expensive, which made exports more expensive. The landlords were old aristo families, and so there was an economic war between manufacturers and aristos. The manufacturers won, and the old families were impoverished with death taxes. It took decades, but strangled they were.

More that the pension system was destroyed, and real estate was a bridge to the poor house ie street sleeper culture that is starting to really take wings now. Only the better off workers the 75 to 95% were able to get into the rental property racket. To quote BTO, “you ain’t seen nothing yet!”