Yves here. While it’s not hard to appreciate the value of this post describing fossil fuel incremental ploys to keep their profits, I’m perplexed by the choice of the word “elongating.” I would have expected “extending” to evoke “extending the life.” Perhaps I get too many of the wrong sort of junk e-mails, but “elongating” has more manhood-enhancing connotations. Perhaps that was the point.

I also have to differ with Neuburger’s claim that every civilization collapses. Some die by conquest.

By Thomas Neuburger. Originally published at God’s Spies

I want to present a group of data points and let you conclude what you will. I’ve already concluded what I will — it’s in the headline. But please be the judge yourself.

Every Civilization Collapses

The first data point is a truism. Consider this, from Michael Klare, writing in The Nation:

“In his 2005 bestseller Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, geographer Jared Diamond focused on past civilizations that confronted severe climate shocks, either adapting and surviving or failing to adapt and disintegrating. Among those were the Puebloan culture of Chaco Canyon, N.M., the ancient Mayan civilization of Mesoamerica, and the Viking settlers of Greenland. Such societies, having achieved great success, imploded when their governing elites failed to adopt new survival mechanisms to face radically changing climate conditions.

“Bear in mind that, for their time and place, the societies Diamond studied supported large, sophisticated populations. Pueblo Bonito, a six-story structure in Chaco Canyon, contained up to 600 rooms, making it the largest building in North America until the first skyscrapers rose in New York some 800 years later. Mayan civilization is believed to have supported a population of more than 10 million people at its peak between 250 and 900 A.D., while the Norse Greenlanders established a distinctively European society around 1000 A.D. in the middle of a frozen wasteland. Still, in the end, each collapsed utterly and their inhabitants either died of starvation, slaughtered each other, or migrated elsewhere, leaving nothing but ruins behind.

“The question today is: Will our own elites perform any better than the rulers of Chaco Canyon, the Mayan heartland, and Viking Greenland? [emphasis mine]

And the climate connection: “As Diamond argues, each of those civilizations arose in a period of relatively benign climate conditions, when temperatures were moderate and food and water supplies adequate. In each case, however, the climate shifted wrenchingly, bringing persistent drought or, in Greenland’s case, much colder temperatures. Although no contemporary written records remain to tell us how the ruling elites responded, the archaeological evidence suggests that they persisted in their traditional ways until disintegration became unavoidable.”

Keep the bolded question in mind; it’s the reason I quoted the passage.

Will our own elites perform any better than the rulers of Chaco Canyon, the Mayan heartland, and Viking Greenland?

Let’s take a look.

Fracking Extends the Fossil Fuel Era

The following 2018 video, though superficially dry, is actually quite accessible. It walks you through four charts, Each one matters; each is easy to understand.

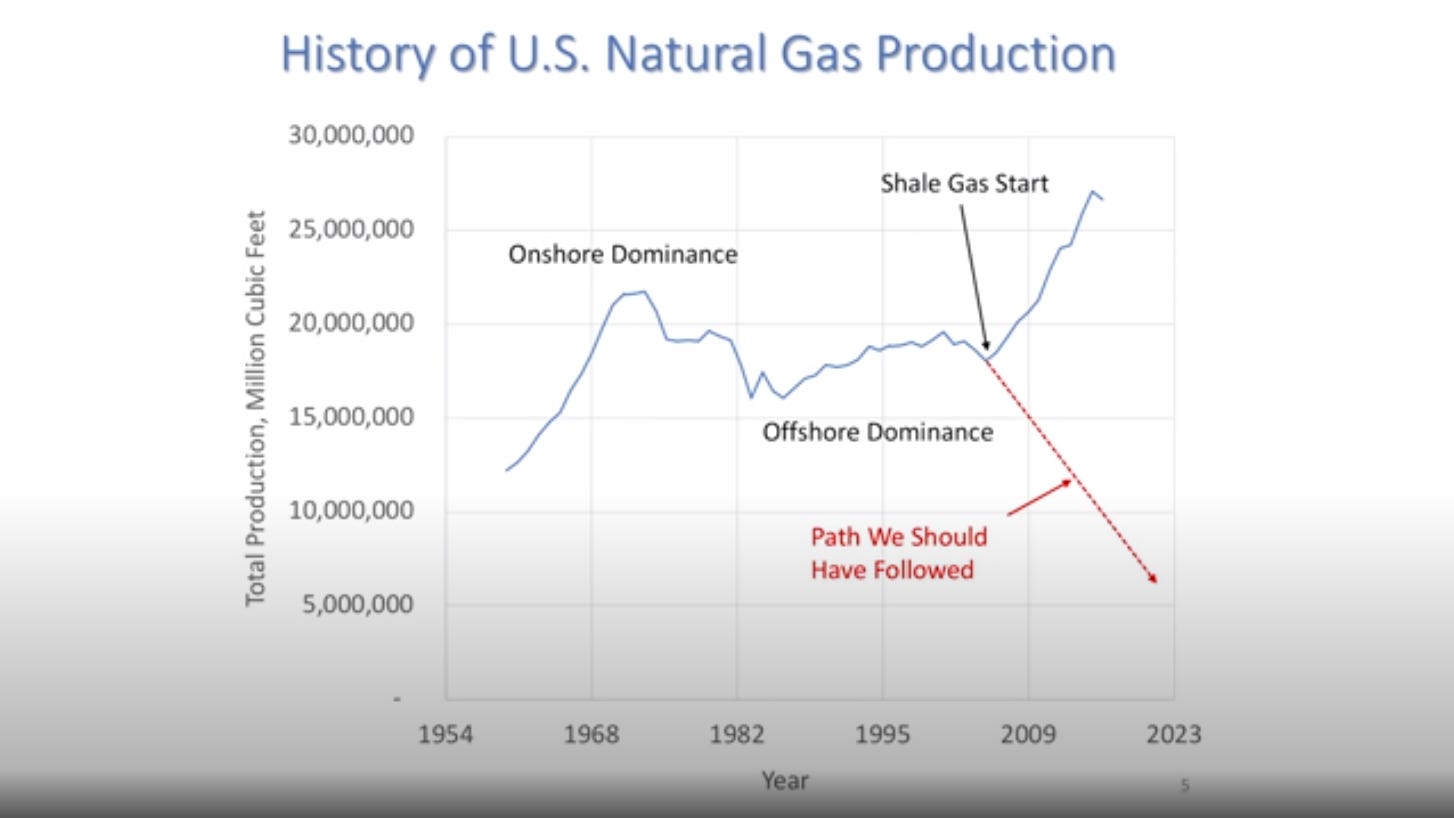

Chart 1 appears at 4:12 in the clip. It shows the history of natural gas production in the United States, beginning with the dominance of onshore production, followed by the dominance of offshore production, followed by what should have been decline. Fracking saved the industry.

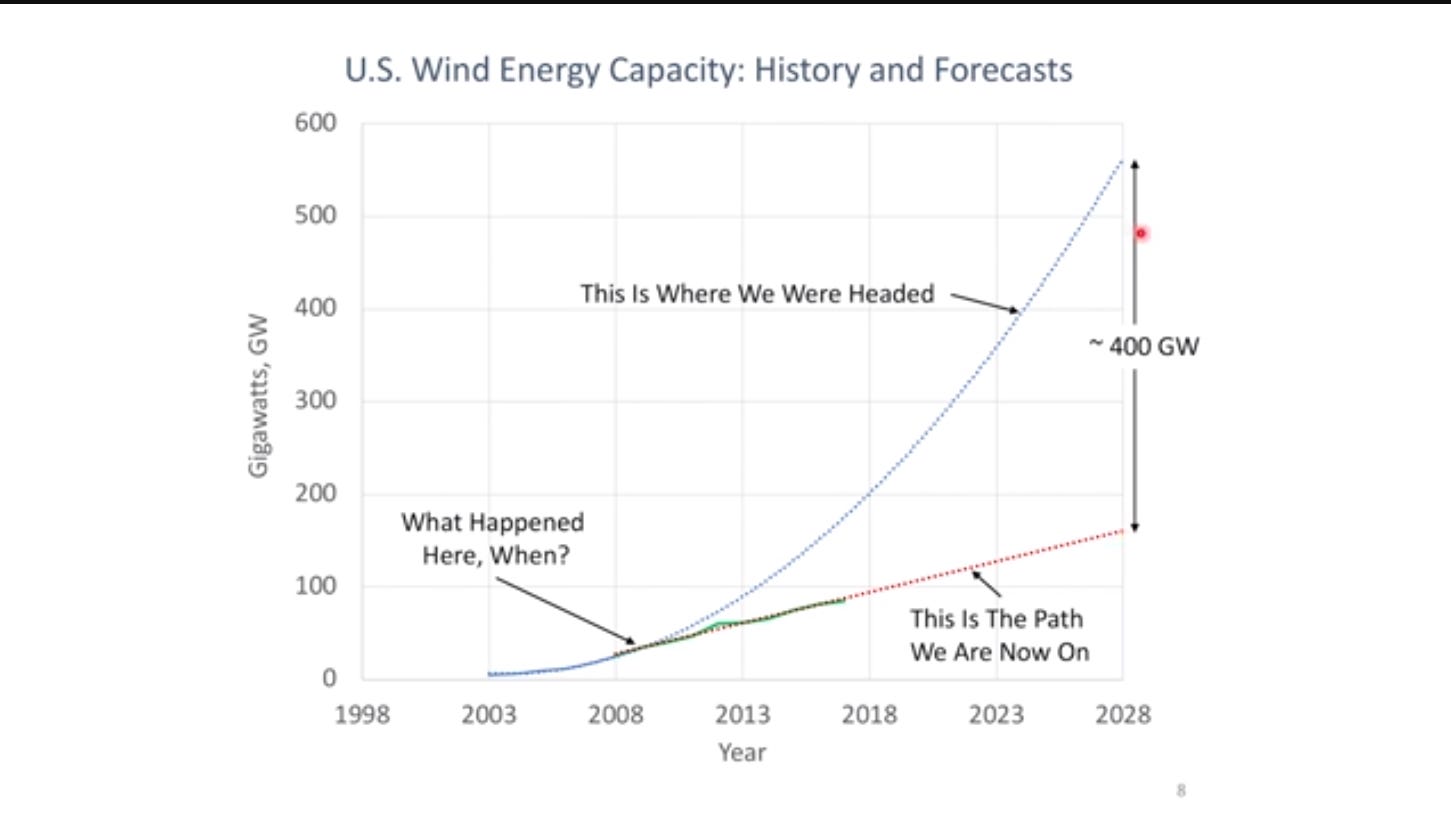

Chart 2 appears in a couple of forms. Let’s look at this, starting with the discussion at 5:30 in the clip. It shows what the exploitation of fracking did to the wind industry.

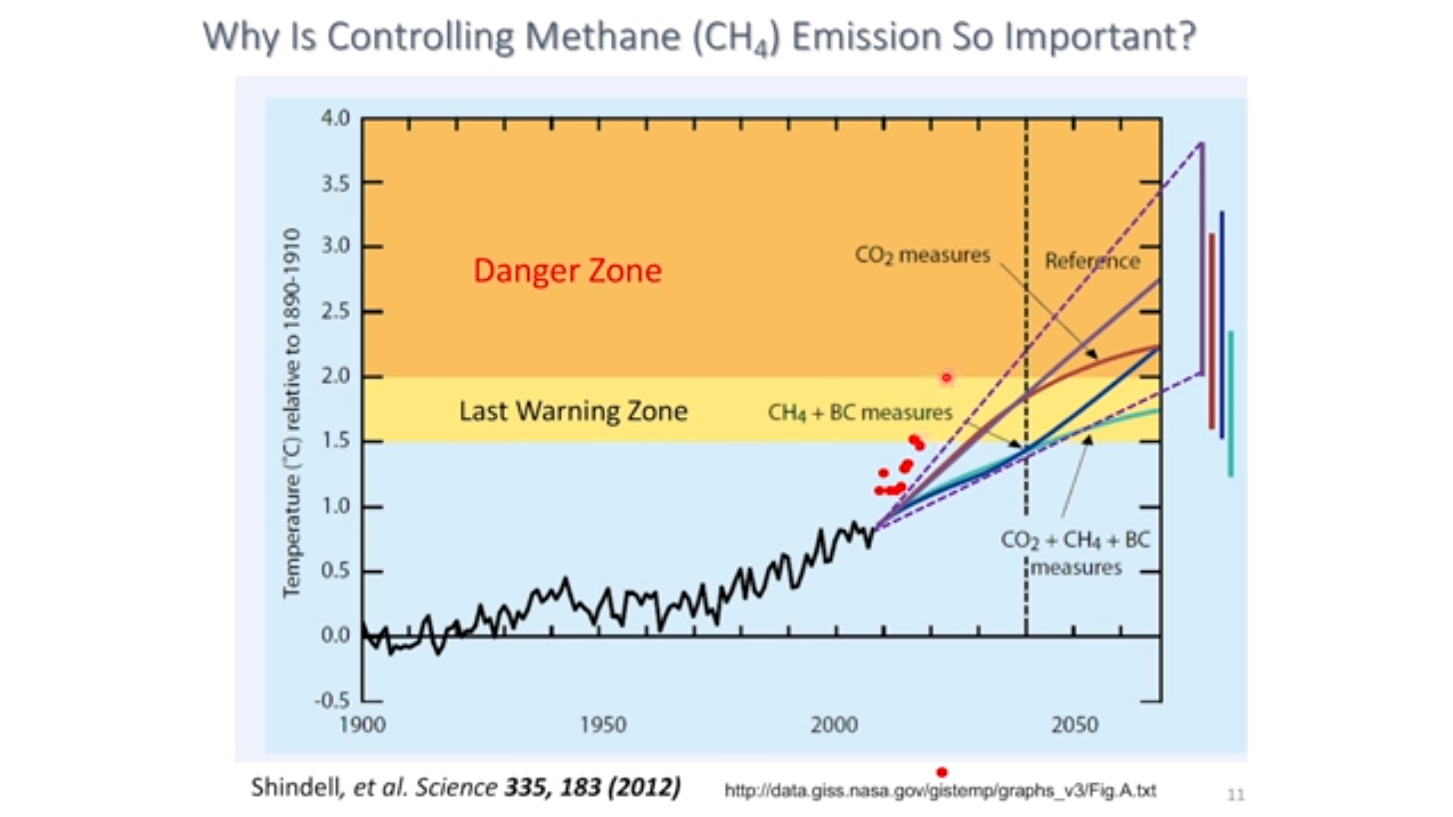

Chart 3 is discussed starting at 6:57. It shows, first, predictions of global warming under several scenarios from a paper published in 2012, followed by subsequent actual global warming (added red dots) over the prediction period.

The highest red dot is an extrapolation. I shows that 2 degrees warming arrives in the 2030s.

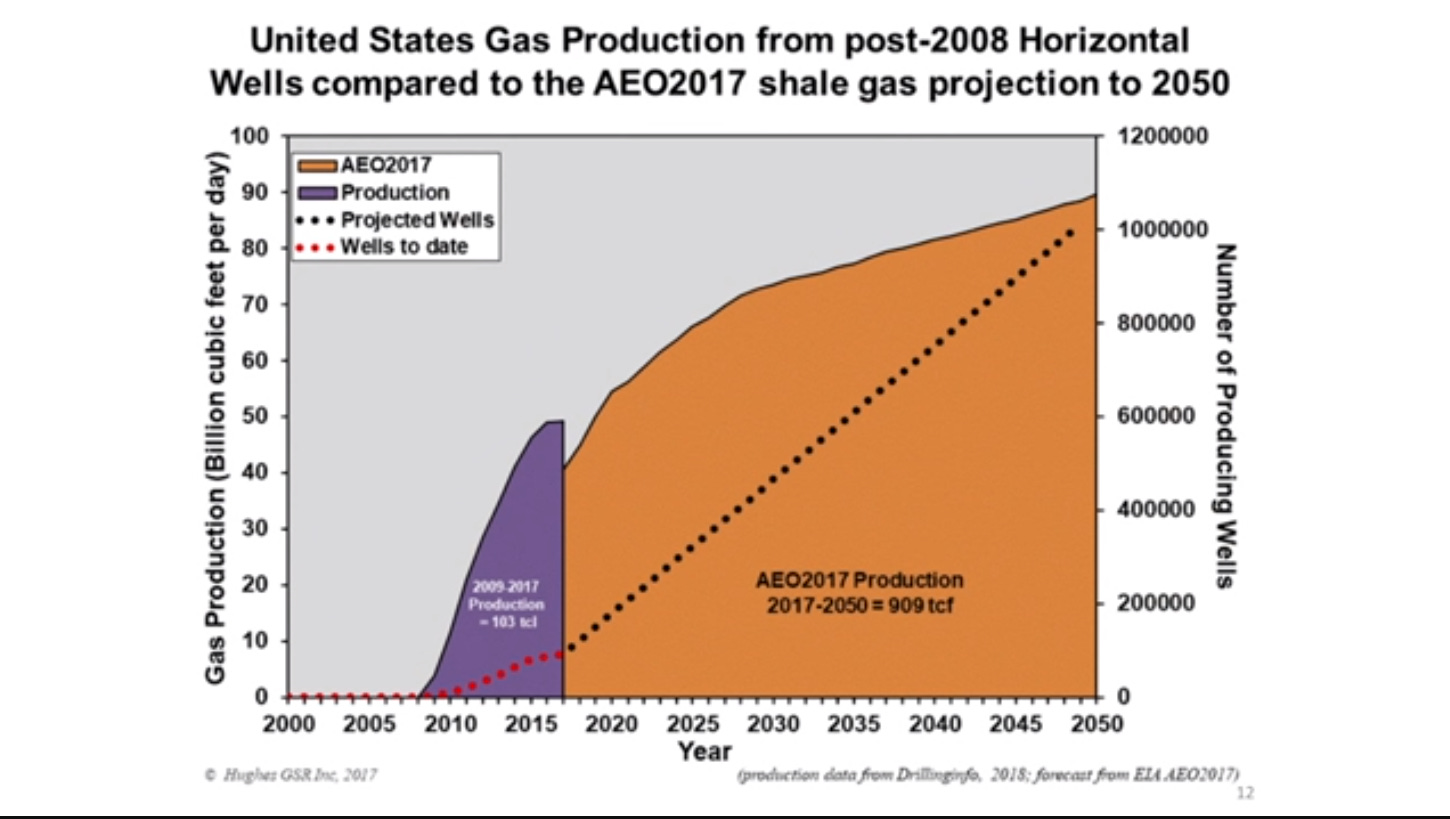

Chart 4 is discussed at 10:80. It shows the future of shale gas (fracking) development. The colored area shows gas produced per day. The dots show the number of wells producing that gas.

The main point of this video, however, appears at 3:41, where the speaker lists the ‘“unintended consequences” of shale gas production:

- Elongation of the fossil fuel era (illustrated by charts 1 and 4)

- Depression of renewable energy supply (illustrated by chart 2)

- Worsening of climate change (illustrated by chart 3)

My question:

Is the elongation of the fossil fuel era an “unintended consequence” of our response to global warming, or the whole point?

Hold that thought as we continue.

The latest godsend, if you believe the mainstream press, is energy from the burning of hydrogen. The formula you normally see is this:

2H2 + O2 → 2H2O

though in the real world, one with a nitrogen-rich atmosphere, the following is more common:

H2 + O2 + N2 → H2O + NOx

Oxides of nitrogen (NOx) are sources of smog and acid rain. They also damage the stratospheric ozone layer. So less than perfect already.

Hydrogen Is a Greenhouse Gas

Even so, you’ll note there’s no carbon in those equations. So is the shiny new hydrogen economy likely to save us? Short answer: No. From a 2022 European Geosciences Union paper, “Climate consequences of hydrogen emissions,” we learn (emphases mine):

“Given the urgency to decarbonize global energy systems, governments and industry are moving ahead with efforts to increase deployment of hydrogen technologies, infrastructure, and applications at an unprecedented pace, including USD billions in national incentives and direct investments. While zero- and low-carbon hydrogen hold great promise to help solve some of the world’s most pressing energy challenges, hydrogen is also an indirect greenhouse gas whose warming impact is both widely overlooked and underestimated. This is largely because hydrogen’s atmospheric warming effects are short-lived – lasting only a couple decades – but standard methods for characterizing climate impacts of gases consider only the long-term effect from a one-time pulse of emissions.”

So atmospheric hydrogen is indeed a greenhouse gas, though indirect; its effect is just shorter-lived than atmospheric CO2. Also, it leaks.

“[T]his long-term framing masks a much stronger warming potency in the near to medium term. This is of concern because hydrogen is a small molecule known to easily leak into the atmosphere, and the total amount of emissions (e.g., leakage, venting, and purging) from existing hydrogen systems is unknown. Therefore, the effectiveness of hydrogen as a decarbonization strategy, especially over timescales of several decades, remains unclear.”

Most Hydrogen Is Produced Using Coal and Other Fossil Fuels

Hydrogen’s questionable usefulness as a decarbonizing strategy hasn’t stopped massive investment in it. If you know how it’s produced, you can see why fossil fuels makers are promoting it (emphasis mine):

“Hydrogen fuel can be made in a number of different ways, often referred to by associated colors. Green hydrogen, for example, refers to hydrogen produced from water, exclusively by using other renewable energy sources such as wind or solar energy to power the process. Gray and blue hydrogen refers to hydrogen produced from methane, using any form of energy to power the process.

“Producing green hydrogen has no direct greenhouse gas emissions. But gray and blue hydrogen production creates carbon dioxide (a planet-warming greenhouse gas) as a by-product, which is then either released into the atmosphere (in the case of gray hydrogen) or captured and stored (in the case of blue hydrogen).

“Black hydrogen is the least environmentally friendly form and refers to a process that uses coal to power hydrogen production. Currently, 99% of the United States’ supply of hydrogen is sourced from fossil fuels such coal, according to the DOE.

“Environmental advocates nationwide have pushed back against gray and blue hydrogen projects, since sourcing the necessary methane to produce the hydrogen could provide revenue for fossil fuel companies, and since the production process creates carbon dioxide, which contributes to harmful climate warming.

“Instead, environmental advocates tend to support green hydrogen, which is produced only with renewable energy.”

If the goal is to extend the fossil fuel industry as far into the future as possible, hydrogen is key. The industry can sell the output (hydrogen power) as “climate-friendly” while continuing to monetize the decidedly unfriendly sources used to create it, like coal (black hydrogen) and methane (blue and gray hydrogen).

Labeling methane-produced hydrogen “blue” was especially brilliant.

Biden Administration Is Building Out Hydrogen Infrastructure

Perhaps that’s why Joe Biden and the industry-friendly Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm are in favor of expanding hydrogen capacity:

“Investing in American Infrastructure and Manufacturing is a key part of Bidenomics and the President’s Investing in America agenda.

“Today, President Biden and Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm are announcing seven regional clean hydrogen hubs that were selected to receive $7 billion in Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding to accelerate the domestic market for low-cost, clean hydrogen.”

For more on Granholm, see here:

I thought the big appeal of hydrogen was its use in fuel cells. Fuel cells, in turn, are an alternative to the batteries that power EVs. (Electrolysis turns electricity and water into O2 and H2, H2 is then stored as a fuel in the pipelines, gas stations, and car tanks, and then the fuel cells in the vehicles turn the H2 and atmospheric oxygen into electricity and water. Storing hydrogen isn’t a trivial issue, but it could be more environmental than mining massive amounts of lithium for conventional batteries.

The problem with hydrogen is that its production requires massive amounts of energy input (Elemental hydrogen is extremely reactive causing it to bind tightly with other atoms, making it hard to split molecules containing hydrogen. Theoretically, Solar & wind generated electricity can be used, but that would require vast resources & investments because renewable energy is much less “energy dense” than fossil fuels. The vision that an array of solar panels on a gas station roof can produce sufficient hydrogen to run auto fuel cells is delusional in the extreme. Hydrogen storage is, perhaps, the least efficient way to store energy.

Thank-you for adding that bit of information about energy inputs. The idea of a gas-station roof powering a fleet of cars is indeed delusional, but the more reasonable case I’ve read about is a solar array on a Amazon warehouse powering the fuel-cell forklifts working in the same warehouse.

What about using natural gas as a hydrogen source instead of water? Is that more efficient than simply burning methane? Plenty of methane leaking out of every swamp, marsh, pig farm, and the thawing tundra already, better to be capturing and using that stuff than fracking shale, mining lithium, and building a whole new electrical grid.

There are already battery electric forklifts and it would be more efficient to charge the batteries from from solar cells on the roof than to use H2 with it’s less efficient generation and energy intensive storage.

Yes. The round-trip efficiency of a storage system based on hydrogen is ~45%, vs. the 85% that’s typically achieved with grid-scale battery storage systems. But JE McKellar’s concerns about “mining massive amounts of lithium” are absolutely on target. The world currently produce batteries at less than 1% of the rate required, and I don’t see it ever ramping up to the scale required.

Indeed, most proposed energy storage systems will never “scale up” as required. There aren’t enough sites suitable for pumped storage. The energy density of flywheels and gravity energy storage systems is much too low. Thermal storage must be sited too close to the point of use and would require excessive retrofitting of existing homes and facilities. The only technology that has any hope of scaling up to the hundreds of TWh required for an all-renewable energy system is hydrogen, even though it has all of the flaws mentioned above. [Or possibly ammonia, but it has an even lower 20% round-trip efficiency and comparable flaws.]

And without adequate storage, the goal of an all-renewable grid (or even a mostly renewable grid) fails. We’d have to run gas turbines (fueled with fracked methane) a high percentage of the time forever. At present, I see only four paths that are technically feasible:

1. Renewables with a massive build-up of hydrogen-based energy infrastructure. But many people will oppose this.

2. Nuclear power. Even more people will oppose this.

3. Force everybody to go on an extreme energy diet. Almost everybody will oppose this.

4. Leave our energy systems largely as-is and learn to cope with climate change as it comes.

And wittingly or not, our political “elites” are effectively steering us down the fourth path with undersized efforts and policies that work at cross-purposes. I hope we can cope.

“3. Force everybody to go on an extreme energy diet. Almost everybody will oppose this.”

True that. We have all been well brainwashed into believing you are what you drive.

That doesn’t change the reality that an “extreme energy diet” is the only effective response to our situation. Neither time nor biophysical realities will allow anything else.

We could get around the storage problem by having an extensive electrial supply grid.

“We could get around the storage problem by having an extensive electrical supply grid.”

Unfortunately, this isn’t true. Having a bigger grid won’t help if none of your generation assets are running due to unfavorable weather. To quote from Revenant’s comment from two days ago regarding Europe:

And for solar, it’s even worse. At 9PM EDT today, the sun will set on the western-most tip of the continental US, and it won’t rise on the eastern-most tip until 7AM tomorrow morning. For the ten hours in between, every single solar panel in the entire continental US will be dark. Mix in a high-pressure calm with PV arrays covered with snow and/or ice, and it’s not at all difficult to imagine needing several days worth of stored energy.

The most credible study I’ve read on storage assumed a greatly expanded grid, and it still required 100 TWh of storage. Mark Jacobson’s infamous “100% WWS” study also assumed an expanded grid, and he came up with a requirement of 546 TWh. [Though in fairness, he was trying to cover transportation and home heating also; not just today’s electricity consumption.] This is just for the US.

Worldwide battery manufacturing is currently ~0.6 TWh per year. We’d need centuries to get enough battery deployed. Even with “an extensive electrical supply grid”.

“There aren’t enough sites suitable for pumped storage.”

I suspect the statement is predicated on not factoring in the use of High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) transmission. Our national grid was built using the technology of the time that did not allow for HVDC and instead we used HVAC, which is very inefficient over distance. HVDC can move power over thousands of kilometers with relatively low loss. If we were serious, we would be switching to a national HVDC grid so as to reach stranded RE, (wind, solar, geothermal) areas far away from metropolitan centers, to link those RE resources with populated areas – just like China has been doing for the last two decades. This would allow solar farms in desert areas with mountains, meaning virtually unlimited opportunity for pumped hydro storage, which is an established technology and highly efficient form of power storage. The reason we’re not doing this is because there’s no profit in renewable energy like there is no profit in storing with pumped hydro. In both cases, there’s no vertical trade, once you buy and install the equipment there’s nothing else to buy/supply. See my video here:https://youtu.be/d45wabqWkMI?si=GZc_qb6IJ_VEVra6

“I suspect the statement is predicated on not factoring in the use of High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) transmission.”

Nope. Both of the studies I quoted (one by Euan Mears and Roger Andrews and the other by Mark Jacobson’s team) omitted transmission constraints to keep the complexity of the analysis bounded. This effectively assumes a continent-spanning network of HVDC, and their estimates of storage requirements were 100 TWh and 546 TWh, respectively.

I live fairly close to the Bath County pump storage station that’s located in western Virginia. It holds 24 GWh of energy, which is more than all of the nation’s grid-scale battery storage systems combined. I’ve actually visited the facility, and it’s very impressive.

But to get to 100 TWh of storage, we’d need over four thousand stations of this size. We currently have seven stations capable of holding more than 5 GWh, and there is one more planned (the Eagle Mountain facility in California, which has been tied up with lawsuits and permitting since 2005; they still haven’t broken ground). If the 546 TWh number by Jacobson is actually correct, we’ll need over twenty thousand Bath County equivalents.

We’ve built approximately one large-scale pumped storage facility per decade, and we’re supposed to build thousands by 2050? To do this we’d have to increase our production rate at least a thousand-fold. It won’t happen.

Article doesn’t make clear that hydrogen is just another energy storage scheme, like batteries, pumped hydro, fly wheels & thermal storage. Also does’t directly address the massive opportunity costs of building a “renewable” energy infrastructure. Nonetheless, it serves to expose the Hydrogen scam.

Hi JE I agree.

There are a few ideas for hydrogen combustion: in gas turbines but that has issues with liquid water hitting the blades. It’s being studied but is a problem. And using as a filler of some 5% in natural gas pipelines which is unknown if it’ll ever happen.

NOX can be controlled pretty well in turbines, not so much in gas stoves.

Storage isn’t that hard. New composites make for great tanks.

What caught my attention was somehow conflating the massive methane leakage from mining/drilling/flairing/ incomplete burning of a raw material with a made product like hydrogen which would have none of that.

Sure I’m some will leak but compared in volume or damage is trivial.

I was watching a test of the nikola truck the other day. They said 75kg of hydrogen for them 500 miles with a full load. I wonder how many kg of lithium batteries with the corresponding minerals would take to do that? And the fill time is measured in minutes.

Hydrogen has its place in the storage/energy system ecosystem.

And those lithium batteries are just as heavy when empty as when they’re full.

I thought the problem with storage wasn’t so much keeping the H2 in, but compressing it to a reasonable volume at a reasonable temperature. Would be great to see airliners replaced with fuel-cell powered airships, though, no volume issues there.

The linked 2021 Neuberger article relies extensively on Food and Water Watch‘s excellent Biden Climate Watch, which has continued to be updated to the present.

Pueblo Bonito, a six-story structure in Chaco Canyon, contained up to 600 rooms, making it the largest building in North America until the first skyscrapers rose in New York some 800 years later.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

About a decade ago 7 of us in 2 vehicles set out from Tehachapi to the campground in Chaco Canyon on an around the west road trip, and 725 miles or so later, collapsed into tents and got up early the next morning and drove to Pueblo Bonito, and we had it all to ourselves for an hour.

It’d be tantamount to having Pompeii for an hour or the view of Yosemite Valley from the viewpoint just after the tunnel on the road to yourself, for an hour.

If the Anasazi had known what was going to hit them in Chaco Canyon, they could have become climate change immigrants, get on a 787 in Albuquerque and off to London you go, or perhaps Tokyo?

Instead, widespread cannibalism was the calling card they left as their culture disintegrated, and all they had to get ‘r done was crude weaponry made out of pointy rocks, no assault rifles.

Read this great book on the history of wood, which of course was largely the only energy source before the age of oil, and like us, the ancients raced through it like there was no tomorrow, many of them denuding precious forests that never returned, others using prudence.

I highly recommend A Forest Journey: The Role of Trees in the Fate of Civilization, by John Perlin.

Some relevant background on how societies respond to climate change and other environmental crises: Navigating polycrisis: long-run socio-cultural factors shape response to changing climate. (open access)

Journalistic overview: The link between environmental disasters and societal collapse, explained.

Excerpt:

Degroot has identified a number of ways that societies adapted to a changing environment across millennia: Migration allows people to move to more fruitful landscapes; flexible governments learn from past disasters and adopt policies to prevent the same thing from happening again; establishing trade networks makes communities less sensitive to changes in temperature or precipitation. Societies that have greater socioeconomic equality, or that at least provide support for their poorest people, are also more resilient, Degroot said.

By these measures, the United States isn’t exactly on that path to success. According to a standard called the Gini coefficient — where 0 is perfect equality and 1 is complete inequality — the U.S. scores poorly for a rich country, at 0.38 on the scale, beaten out by Norway (0.29) and Switzerland (0.32) but better than Mexico (0.42). Inequality is “out of control,” Hoyer said. “It’s not just that we’re not handling it well. We’re handling it poorly in exactly the same way that so many societies in the past have handled things poorly.”

Arthur Berman, a petroleum geologist with 36 years of oil and gas industry experience, gave a talk at the Energy Institute of the University of Texas at Austin on Sept. 12, 2023.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2lW3D3hs1WU

Points he emphasized: So far, no replacement of fossil fuels by renewable energy has taken place. It is not just carbon dioxide and climate, but many aspects of the environment and the biosphere, which are impacted by human modern techno-industrial civilization. There will be no willing reduction of energy use and economic growth prior to a very impactful event, in his view, and there will be a necessarily substantial reduction of human population as a consequence.

Maybe something surprising will happen instead — but probably not, he thinks.

Thanks for this link.

This is a peculiar post. The question: “Will our own elites perform any better than the rulers of Chaco Canyon, the Mayan heartland, and Viking Greenland?” leads into a discussion of fracking. From there it discusses hydrogen power and the Biden plan to build out hydrogen infrastructure. Any one of these three topics for discussion deserves its own post but I am not sure I see the value in clumping them all together to conclude with “Visit Canada”.

I think it might be better to focus on the question raised at the beginning of this post. Sadly — in the case of this question — I believe past performance is indeed indicative of future results. Fracking and/or Biden’s hydrogen giveaway might be used as a warrant for arguing this view of the elites. I believe this post quickly becomes involved with details of fracking and hydrogen that only weakly bolster what I believe should be the crux of the argument in this post.

The concluding pair of questions: “Are we really really in control of “our response” to global warming? If not, what should we do?” deserve a post or many posts exploring answers.

I believe “our” elites have been and are working long and hard to hasten the Collapse of the u.s. Empire. As a retired and very unimportant minion of that Empire, I am mystified and very frightened. Worse, “our” elites will leave no assets stranded — the rest of the world be damned. I am so crazy I no longer believe “our” elites are human. I see no shiny “solution” to the Collapse of fossil fuels and resources looming within decades of my last years. I believe this will mean the Collapse of Society, Civilization, and life as we have known it. I am very very frightened that the coming Climate Chaos and world devoid of large populations of the animals and plants we know today, and full of new diseases and parasites, could subject Humankind to the judgments of a bitter crucible in making passage to the unknown lands of the all too near future. In answer to the last question raised by this post — we have no control over the response to global warming nor the response to any of the manifold crises of the future. What should we do? I have no idea. I cannot ease the way of my own children as they devolve into madness. I believe there will be bloody revolution and I believe the very most fortunate of the wealthy will die sealed and entombed within their bunkers.