Yves here. It is useful and welcome to see data, as opposed to conjecture and assertion, around the position of the dollar. We’ve argued that the logical reserve currency successor by virtue of the size of the underlying economy, China’s renminbi, is not likely to assume the role soon if ever. For starters, China is unwilling to assume the burden of running regular trade deficits and eschewing capital controls. The Euro ceased being a candidate after the 2008 crisis exposed its limitations and Eurozone governments weren’t willing even to consider possible reforms. But some smaller currencies are gaining ground.

By Wolf Richter, editor at Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

The US dollar has been the dominant global reserve currency for decades, amid many global reserve currencies. And there are lots of people, institutions, and governments that want to see an end to this “dollar hegemony.”

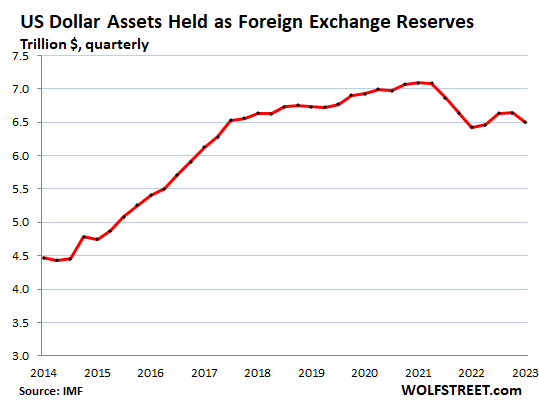

But central banks other than the Federal Reserve are still holding large amounts of US-dollar denominated assets – $6.5 trillion in total – such as US Treasury securities, US government-backed MBS, US corporate bonds, US agency securities, even US stocks (the Swiss National Bank), all of which combined make up the USD-denominated foreign exchange reserves that central banks other than the Federal Reserve hold.

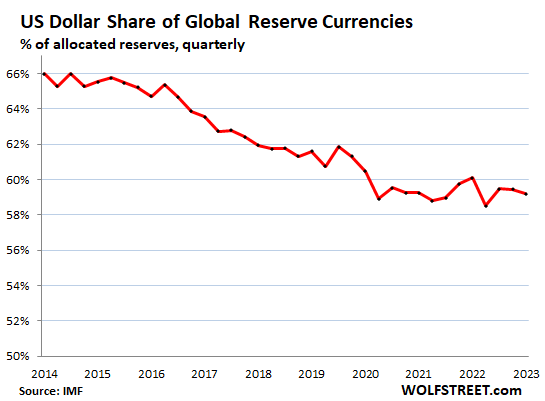

The share of USD-denominated foreign exchange reserves dipped to 59.2%, according to the IMF’s COFER data released on December 31 for Q3 2023. For the past 20 years, the USD’s share has been on a slow downward trend, with other currencies nibbling at it from all sides. The euro was #2, the yen #3, the British pound #4. The Chinese renminbi dropped to #6, behind the Canadian dollar (more on all those in a moment):

In dollar terms, the holdings of USD-denominated assets at foreign central banks dipped to $6.5 trillion. Note that the Fed’s holdings of Treasury securities and MBS are not included in foreign exchange reserves. No central bank’s holdings in its own currency are included.

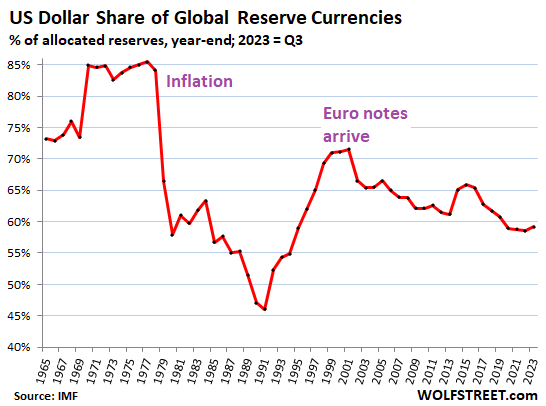

Since 1965, the USD’s share of global reserve currencies has gone through a tumultuous history, including the collapse of its share starting in 1978 through 1991 from 85% to 46%. This came after inflation exploded in the US in the late 1970s, and the world lost confidence in the Fed’s ability to manage inflation. And the decline of the USD’s share continued even as inflation began to fade in the 1980s.

But by the 1990s, confidence returned gradually and the dollar’s share rebounded until the euro came along and put a stop to the gains by the USD (2023 through Q3)

The Other Major Reserve Currencies

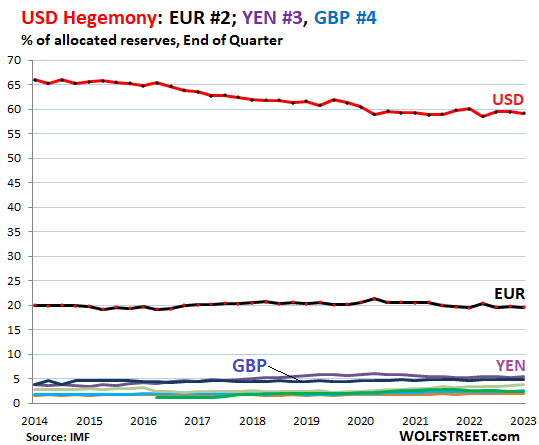

The euro’s share (#2) has been roughly stable at around 20% for years. In Q3, it dipped to 19.6% (black line, red dots in the chart below). The other currencies are the colorful tangle at the bottom of the chart:

The USD Is Losing Ground Against the Tiny “Other Currencies” Combined

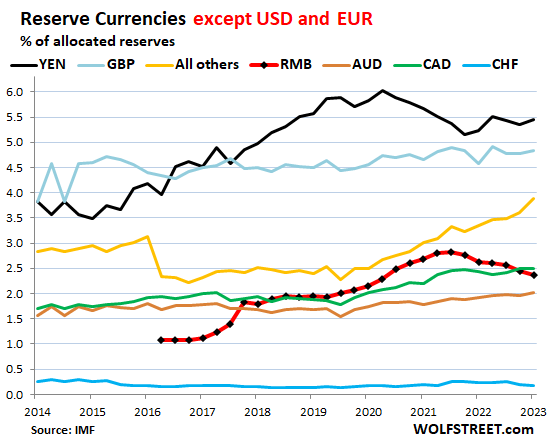

The chart below shows the colorful tangle magnified. China is the second largest economy in the world, yet its currency plays only a minuscule and declining role as a reserve currency, and is no threat to the US.

But note the surge of the yellow line, “all other currencies” combined, each of which has a smaller share than even the swiss franc, but combined, they’re making headway.

- #3, Japanese yen, 5.5% (purple).

- #4, British pound, 4.8% (blue).

- #5, Canadian dollar, 2.5% (green), bypassing the Chinese renminbi.

- #6, Chinese renminbi, 2.4%, sixth quarter in a row of declines, lowest since Q4 2020 (red), amid the reality of capital controls, convertibility issues, and other issues. Central banks appear to be leery of holding RMB-denominated assets.

- #7, Australian dollar, 2.0% (brown).

- #8, Swiss franc, 0.18% (blue).

- “All other currencies” combined (yellow) have a total share of 3.9%. The largest one of them has a share even smaller than the Swiss franc’s share of 0.18%. But their combined share has risen from 2.5% in 2019 to 3.9% currently. These tiny reserve currencies combined are taking share from the USD:

Dollar-Exchange Rates and Foreign Exchange Reserves.

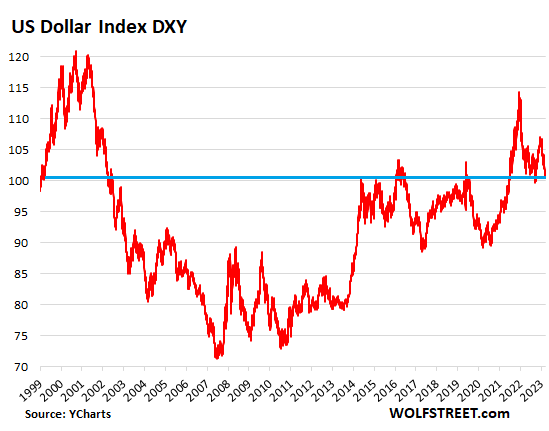

The USD exchange rate matters. Foreign exchange reserves are measured in USD. For reporting and comparison purposes, the holdings in EUR, YEN, GBP, CAD, RMB, etc. are translated into USD figures at the exchange rate at the time. So the exchange rates between the USD and other reserve currencies change the magnitude of the non-USD assets – but not of the USD-assets.

For example, Japan’s holdings of USD-denominated assets are expressed in USD. But its holdings of EUR-denominated assets are translated into USD at the EUR-to-USD exchange rate at the time. So the magnitude of Japan’s holdings of EUR-assets, expressed in USD, fluctuates with the EUR-to-USD exchange rate, even if Japan’s holdings don’t change.

The exchange rates between the USD and other currencies can fluctuate wildly. The yen dropped a lot in 2022 and then again in 2023 against the USD. So the value of yen-denominated assets held by central banks (other than the Bank of Japan) would have declined when expressed in USD, and it would have pushed down the share of the yen-denominated foreign exchange reserves expressed in USD.

But over the long run, the currency pairs are amazingly stable, despite massive fluctuations in between. The Dollar Index [DXY], which is dominated by the euro and yen, is back at 101, where it had been in 1999 (data via YCharts):

Hi all, and thanks for sharing the interesting article, Yves.

I think the role of China’s renminbi (RMB) in this process is worth considering, even if China doesn’t alter its current public policies.

Most nations worldwide run persistent trade deficits with China, making the RMB a necessary currency for these countries, especially in industries that are heavily involved in cross-border transactions. These industries, representing significant portions of their national economies, have a continuous demand for the RMB and tend to hold a certain amount of it. Consequently, these sectors can potentially conduct some of their trade in RMB, utilizing the currency that’s already circulating globally.

While this shift alone wouldn’t amount to a complete dedollarization, it’s a piece of a larger puzzle. If various countries start trading more in their domestic currencies or in currencies like the RMB, these partial replacements could collectively lead to a notable reduction in dollar usage, at least for international transactions. This scenario represents an “all of the above” approach to dedollarization, where multiple smaller shifts collectively contribute to a larger trend.

The implications of such a shift are profound and, to some extent, unpredictable. In times of significant historical change, various unforeseen developments can emerge. The potential decline in the dominance of the US dollar, influenced by these multiple, smaller shifts in global currency usage, could pave the way for a new era in international finance and trade, the full effects of which remain to be seen.

Sorry, if what you were saying were accurate, you’d see the renminbi rising as a share of non-Chinese central bank reserves. It has been falling instead. China settles with its biggest export buyer, the US, in dollars.

This chart shows that export invoicing in Asia-Pacific is predominantly in dollars:

https://www.csis.org/analysis/its-all-about-networking-limits-renminbi-internationalization

Hi Yves, thanks for the reply!

Your point about the current state of the RMB in non-Chinese central bank reserves and its limited role in export invoicing in the Asia-Pacific region, especially with the U.S., is well-taken. It’s indeed important to consider such concrete data when discussing international financial trends.

However, I’d like to offer a different angle on this situation. Central bank reserve decisions are multifaceted and influenced by a variety of factors, some of which might not be immediately apparent or publicly disclosed. These considerations can range from economic stability and market liquidity to geopolitical strategies and long-term financial planning. Therefore, the current composition of central bank reserves may not fully reflect a potential future shift in currency preferences, especially in response to significant global events or changes in the economic landscape.

Additionally, the argument I presented primarily focuses on the potential for sectors within various national economies, which are not directly linked to U.S.-China trade, to conduct a portion of their trade in RMB. This perspective considers a scenario where industries in different countries, due to their existing trade relations with China and the consequent demand for RMB, might find it increasingly pragmatic to conduct some of their transactions in RMB, especially in trades that do not involve the U.S. This shift could be part of a broader trend of diversifying away from the dollar in international trade, albeit not an immediate or complete transition.

While the current dominance of the U.S. dollar in global trade invoicing, including U.S.-China trade, is undisputed, the potential for change in other trade sectors shouldn’t be overlooked. The international financial system is dynamic and can be influenced by various unforeseen developments. The prospect of industries in different countries incrementally using the RMB for certain transactions reflects this potential for gradual change, influenced by their specific economic ties with China.

In Conclusion, while the current data on central bank reserves and trade invoicing practices provide a clear picture of the present situation, they may not fully capture the nuances of future trends or the diverse considerations of central banks and industries worldwide.

I hope 2024 is starting off well for you,

Mike

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=lwgj

January 30, 2018

Total Reserves excluding Gold for China, 2007-2018

[ Reserves are at least $4.2 trillion, counting China’s sovereign wealth fund. Also, China has had a current account surplus every year since 2000.

BRICS and the BRICS New Development Bank have just added Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Iran, Egypt and Ethiopia. Algeria has applied for BRICS and joined the BRICS bank. ]

Yes! This is indeed a meaningful development. However, my personal viewpoint, which is certainly open to fallacy, is that it will represent just a small brick in the wall (pun intended :)). I believe that a plethora of developments will be what ultimately dethrones Humpty Dumpty.

Happy New Year!,

Mike

I believe that a plethora of developments will be what ultimately dethrones Humpty Dumpty.

[ Agreed completely, and I much appreciate your comments. ]

It is unlikely that the US will relinquish dollar dominance without resorting to war.

Yes. When the dollar slides will inflation take off? Since we buy almost everything from China and it will cost more and more as the dollar slides. Public sentiment is now ripe to start a war with China and Pentagon brings back the draft and heigh ho?

Imo increasing tensions with China will lead to dueling sanctions, reduced trade and higher inflation., mostly us. The main result would seem to be an acceleration of the ongoing reduction of trade between the west and rest that is already impoverishing eu as it focuses minds among the rest.

Actual hot war a la Ukraine would likely lead to us using the same weak tools, confiscation of China dollar credits and very widespread sanctions that hurt the us far more than China; China would likely undergo a crash course to shift a bit from their export model to more social services that then encourages less saving and more internal consumption while the U.S. copes with reduced imports/consumption and sharply higher prices.

However, hot war seems very unlikely in the next few years, imo draft is a non-starter, the us is very unprepared having a much depleted arsenal after Ukraine and ME wars and with unreliable ships and planes, to say nothing of the vast distance across the pacific.

I absolutely can’t see trump agreeing to a hot war, and maybe not even more sanctions – tech doesn’t seem to like them. Maybe limited to old less competitive industries like steel and cars.

At that point would all those countries currently cowed by the US be no longer controlled (frightened ) by them?

Ernest Hemingway

“How did you go bankrupt?”

Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

I guess we are in the gradual phase.

My point – it is dangerous to extrapolate non-linear, unstable systems too far into the future.

INflating its way out of all the debt accumulated in stupid imperial wars and occupations is the USA’s MO and this has not changed, apparently. It’s just mind boggling to me that the USD is still as strong as it is. At least officially – trinkets and geegaws are still cheap, if crapified, but salad greens, eg. are way more expensive AND lower quality than they were 3 or 4 years ago.

1. How much of these foreign reserves are against USD denominated debt? If a country took on USD denominated debt, then it makes sense to keep reserves in USD to pay off that debt to hedge FX risk

2. The graph shows an increase since 2014 with a slight reversal in 2022. Both the upward and the reversal is an effect of QE and not necessarily the increased usage or reserves of USD

3. Absolute values in a fiat currency doesn’t tell the full picture. Questions that clarify:

Separate out G7 countries from the rest

a. How are the amounts changing in the Foreign Central Banks since 2014 in absolute terms? First Order and Second Order derivative?

b. How are the amounts/total USD denomnated assets Foreign Central Banks since 2014 in absolute terms? First Order and Second Order derivative?

Those answers should tell you if it’s just nominal increase and how fast the change is.

The first graph doesn’t tell the whole story.