Yves here. This article seems likely to give some readers heartburn. For instance, “median wealth” covers a lot of sins. Second, you can’t pay bills with (purported) wealth increases unless you monetize them.

IMHO, most of these discussions miss a key point. What causes households and investors trouble is not inflation but changes in the rate of inflation, typically increases. If the US had, pick a number, 2%, 3% or even 4% inflation, and it varied by only 0.5% in either direction over a year, businesses, labor negotiators, households and investors could plan with a bit of a degree of certainty. Importantly, longer-dated assets would be priced to reflect (pretty accurate) inflation forecasts and would be less risky buys than in highly variable inflation.

By Edward Wolff, Professor of Economics, New York University. Originally published at VoxEU

Central banks and the media have focused on the negative effect of inflation on real incomes. While this income effect is particularly salient for consumers, the overall impact of inflation is a combination of a negative income effect and a positive wealth effect. This column argues that the net impact of inflation on median wealth was positive in the US over the 1983-2019 period, and it also decreases wealth inequality when compared with the top 1%. Conversely, the recent drop in inflation is bad news for the middle class.

The media and the Federal Reserve Board of Washington (‘the Fed’) are obsessed with the negative side of inflation – its effect on real incomes. On the basis of the Consumer Price Index, 1 the annual inflation rate reached a peak of 9.1% in June 2022, the highest level since June 1982, though it has since fallen to 3.1% in November 2023. On the current account front, this means that real income has eroded. This is the ‘income effect’ of inflation.

However, there is an upside to inflation as well. Indeed, inflation has been a boon to the middle class in terms of its balance sheet. It is also a factor that has helped to promote real wealth growth and reduce overall wealth inequality. 2

A simple example can illustrate this point. Suppose a person holds $100.00 in assets and has a debt of $20.00. Her net worth is then $80.00. Suppose inflation is running at 5% per year and the value of her assets also goes up by 5% over the year. Then, in real terms the value of her assets remains unchanged over the year. But what about her debt? In real terms her outstanding debt is now down by 5% and the real value of her net worth rises to $81.00 (100 – 20 x 0.95). In other words, the person’s real net worth is now up by 1.25% (81/80). It should be clear that the higher the ratio of debt to assets, the greater the percentage increase in net worth. (This, by the way, is the principle of leverage). For example, if the debt is $40.00 instead of $20.00, then net worth would grow by 3.33% (62/60).

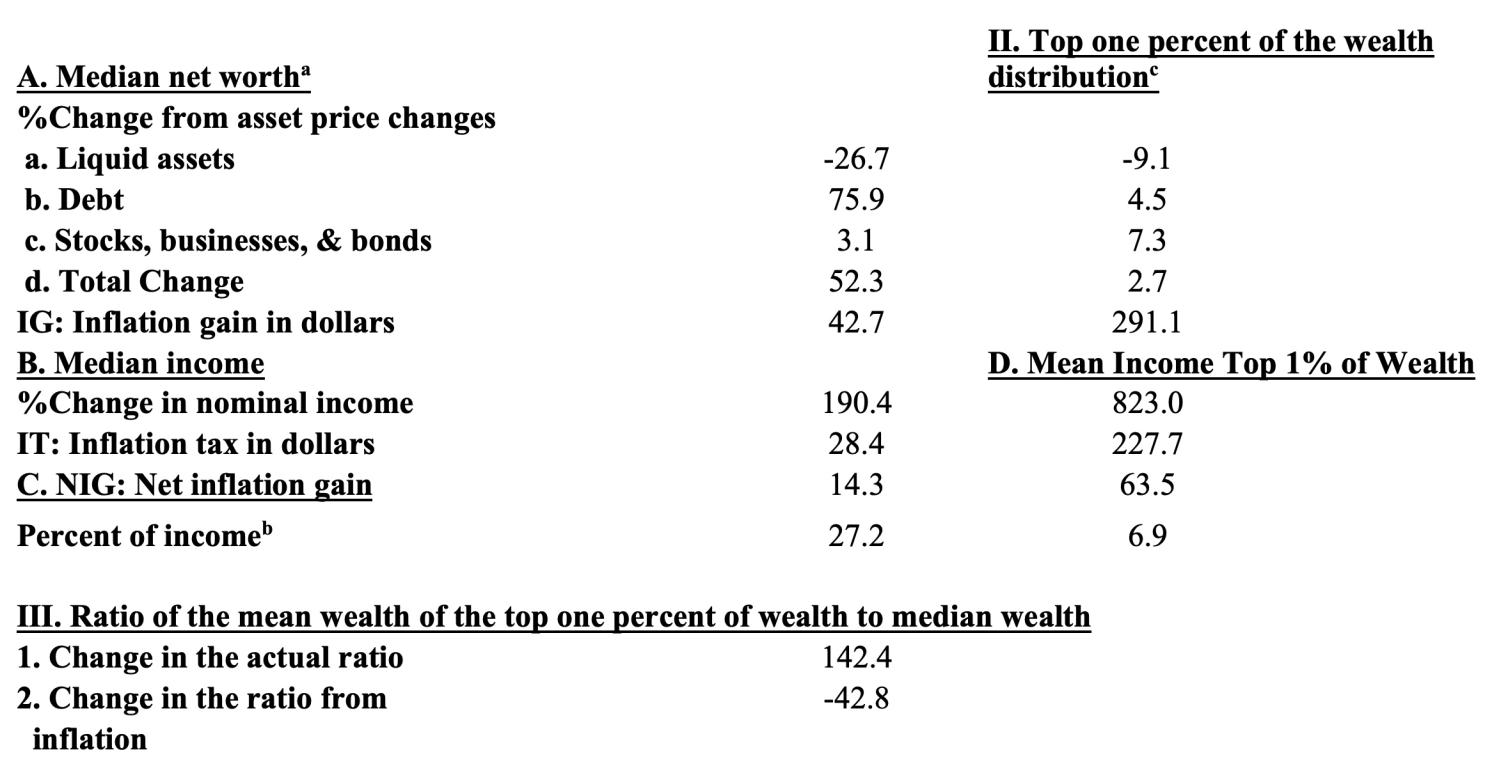

What is the net effect of inflation? The best way to decide on this issue is to compare the income effect of inflation with the wealth effect. If the income effect (which is always negative as long as inflation is positive) is greater, then the net effect is a loss. However, if the wealth effect is greater, then the net effect is a gain. Now, at least until recently, inflation has been quite moderate. Indeed, based on Current Population Survey data, real median household income actually rose by 34.4% from 1983 through 2019. However, without any inflation, median income would have grown by 229%. In dollar terms this amounts to a loss of $30,200 (in 2019 dollars) over these years. On the other hand, inflation by my calculations bolstered median wealth by 52.3% over these same years and this equals $42,700 in 2019 dollars (see Table 3). That is quite a bit greater than the income loss from inflation and here the wealth effect dominates the income effect. So, in terms of household well-being, inflation on net has been a boon to the middle class.

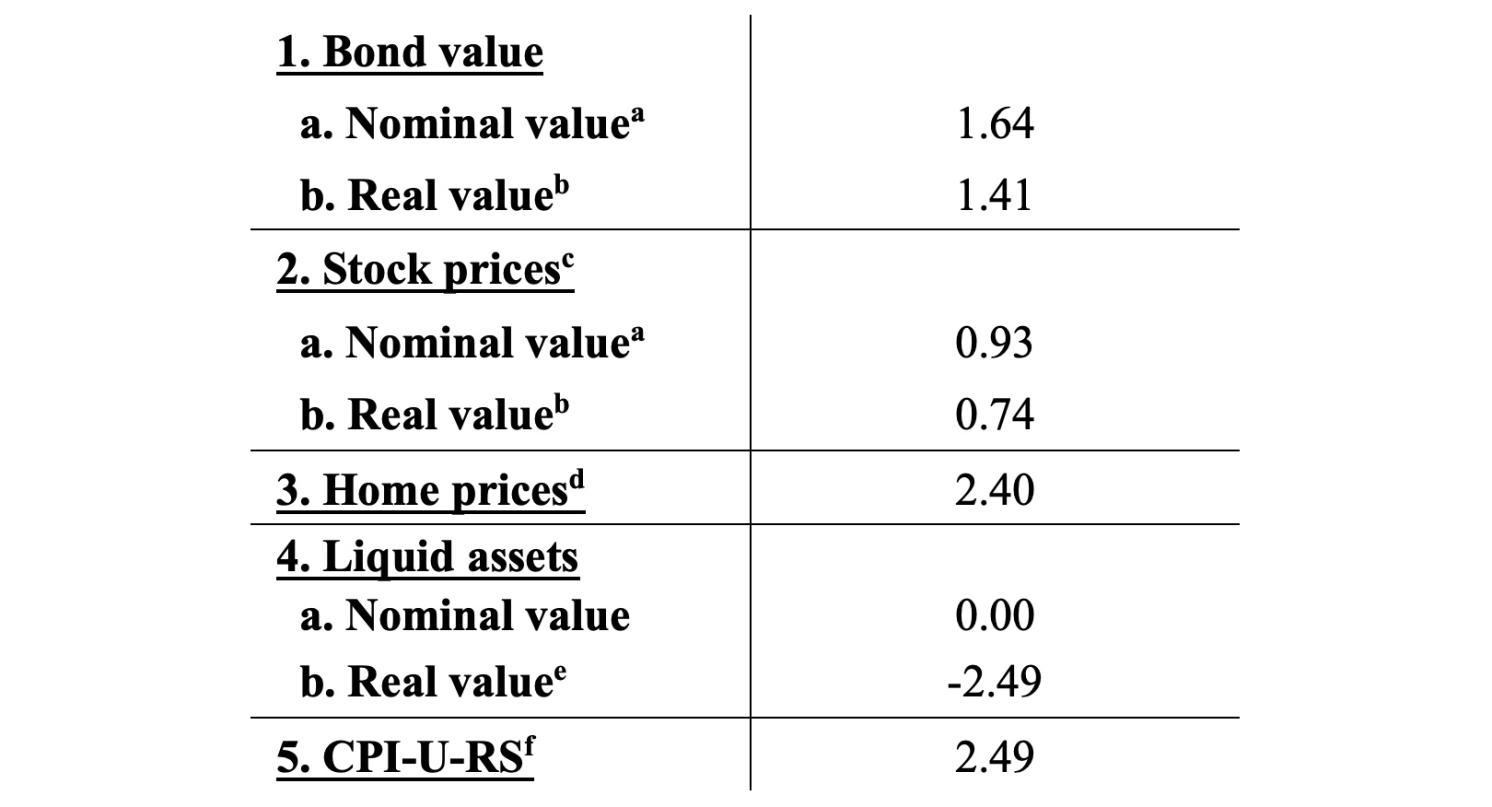

The effect of inflation on the household balance sheet is more than just leverage. There are also impacts on bond values, stock values, and the value of liquid assets. Table 1 shows the time trends in the key ingredients for the analysis of the net inflation gain for years 1983-2019. By far the fastest rate of increase occurred for home prices and debt, 2.40% and 2.49% per year, respectively. This was followed by real bond values, at 1.64% per year, and then stock prices at 0.74% per year. In contrast, the real value of liquid assets declined at an average annual rate of 2.49%, mirroring that of the CPI-U-RS index.

Table 1 Annual rate of change by asset type and debt, 1983-2019 (percentage)

Note: a. Based on US Treasury Securities (Constant Maturity): Ten-year nominal bond rate for ten-year period. b. Based on US Treasury Securities (Constant Maturity): Ten-year real bond rate for ten-year period c. This is based on my calculation of the present value of future profits. See Wolff (2023) for details. d. Based on 30-Year Fixed Rate Mortgage Average in the US, Percent, Weekly, Not Seasonally Adjusted Equivalent monthly payments: 30-year mortgage and 20% down payment. e. The CPI-U-RS is used as the deflator. f. Source: https://www.bls.gov/regions/mid-atlantic/data/consumerpriceindexhistorical_us_table.htm.

It is also of note that when comparing real and nominal trends, differences are relatively small. The annual rate of change in the nominal value of bonds was 1.64%, compared to 1.41% for real values, and those in stocks were 0.93% and 0.74%, respectively. The higher values for the nominal series are due to the fact that the differential between the nominal and real rate of change narrowed over these years because inflation fell.

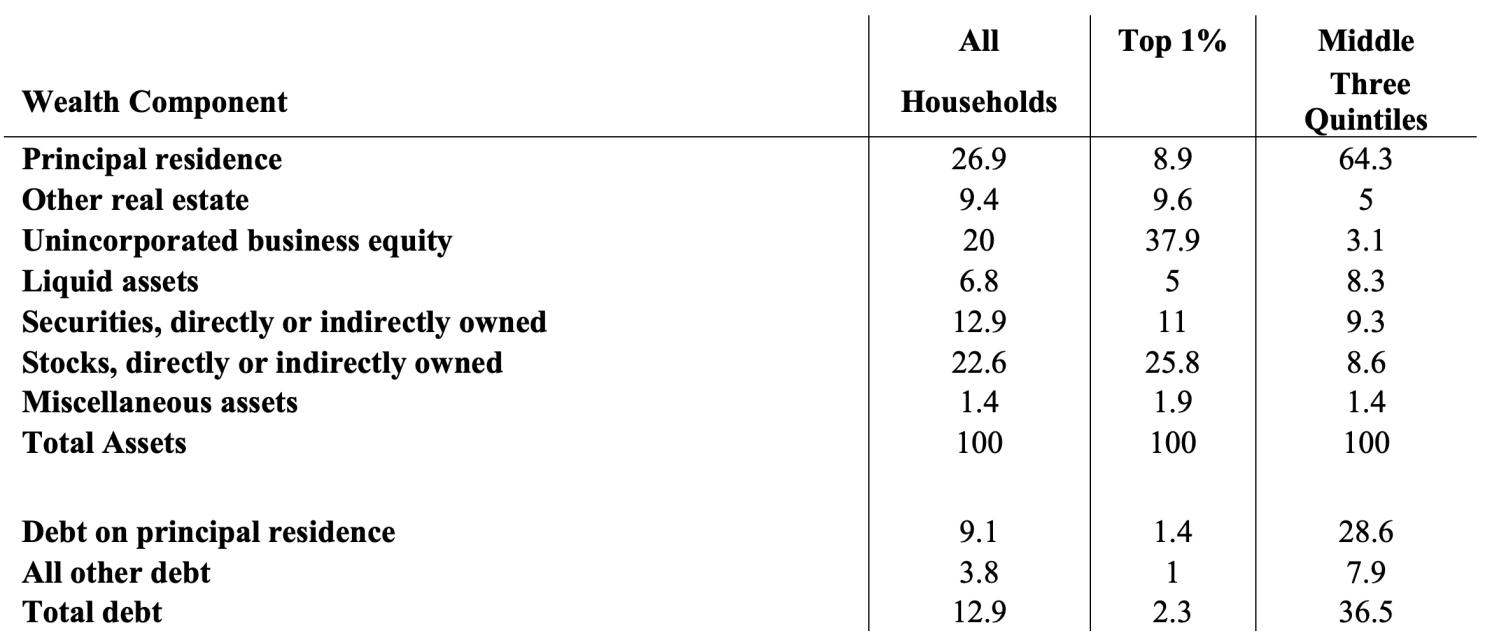

Different groups will experience inflation differently depending on the composition of their wealth. Table 2 presents the ‘consolidated’ wealth accounts in which stocks and bonds owned indirectly through defined contribution plans like 401(k)s and individual retirement accounts (IRAs), mutual funds, and trust funds are allocated to their constituent elements. In 2019 owner-occupied housing was the most important household asset among all households, accounting for 26.9% of total assets. Real estate, other than owner-occupied housing, comprised 9.4%, and business equity another 20.0%. Demand deposits, time deposits, money market funds, certificates of deposit (CDs), and life insurance (collectively, ‘liquid assets’) made up 6.8%. Financial securities, on the other hand, amounted to 12.9% and corporate stocks 22.6%. The debt-net worth ratio was 14.9% and the debt-income ratio 104.0%.

The tabulation in the first column provides a picture of the average holdings of all families in the economy, but there are marked differences in how middle-class and rich families invest their wealth. The largest asset among the richest 1% was business equity, which comprised 37.9% of their total assets. Stocks were second, at 25.8%, followed by securities and then other real estate. Housing accounted for only 8.9% and liquid assets 5.0%. Their debt-net worth ratio was only 2.4% and their debt-income ratio was 45.3%.

In contrast, 64.3% of the assets of the middle three wealth quintiles of households was invested in their own home. However, home equity amounted to only about a third of total assets, a reflection of their large mortgage debt. Another 8.3% went into monetary savings of one form or another. The remainder was split among non-home real estate, business equity, financial securities, and corporate stock. Their debt-net worth was 57.5%, and their debt-income ratio was 122.0%, both much higher than those of the top percentile.

Table 2 Composition of household wealth by wealth class, 2019

Consolidated accounts (percent of gross assets)

Source: Author’s computations from the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances.

Note: Households are classified into wealth class according to their net worth. Brackets for 2019 are: Top 1%: Net worth of $11,115,200 or more. Quintiles 2 through 4: Net worth between $20 and $471,600.

How do asset price movements resulting from inflation affect the wealth position of these two groups? With regard to median wealth, they led to a hefty 52.3% gain in median wealth over 1983-2019, compared to the actual advance of 23.4% (see Table 3). The devaluation of debt by itself led to a 75.9% advance, while the reduction in the real value of liquid assets subtracted 26.7%. The other components of wealth were unimportant. In dollar terms, the inflation gain IG was $42,700. In contrast, the inflation tax, IT, on median income amounted to only $28,400, so that the net inflation gain, NIG, was a robust $14,300 or over a quarter of median income.

Table 3 The inflation tax on median net worth and the mean net worth of the top 1% of the wealth distribution, 1983-2019

Source: Author’s computations from the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) based on nominal and real 10-year bond rates for 10 years.

Note: Dollar figures are in 1000s, 2019 dollars. Households are classified into wealth class according to their net worth. Wealth and income figures are deflated using the Consumer Price Index CPI-U-RS. a. The mean wealth of the middle three wealth quintiles is used to compute the composition of wealth of for the median wealth group. b. Mean value over the period. c. Results based on the mean wealth of the top one percent of the wealth distribution.

In contrast, inflation led to only a 2.7% growth in the mean wealth of the of the top wealth percentile. The main contributor to this gain, 7.3%, was the appreciation of stocks, businesses, and bonds collectively. The depreciation of debt contributed another 4.5% and this was offset by 9.1% from the loss of value of liquid assets. Overall, the mean wealth of the top percentile rose by 2.7% from asset price changes. In dollar terms, the inflation gain was $291,100. The inflation tax IT on the mean income of this group came to $227,700, so that the net inflation gain was a positive $63,500. It might seem surprising that the net inflation gain was positive since this group has very low leverage (that is, a very small debt to net worth ratio). However, the key is that this group also had an extremely high wealth/income ratio of 23.5, so that the wealth effect dominated the income effect.

The inequality analysis is based on the ratio of the mean wealth of the top 1% to median wealth. I can then determine what portion of the change in this ratio is due to asset price changes emanating from inflation. On the basis of this measure, actual wealth inequality increased over the period 1983-2019 (first row of Panel III). The next row shows what happens to the wealth ratio when asset price changes resulting from inflation only is added to initial wealth. The upshot is that inflation reduces the wealth ratio, and the effect is quite large. Over the full 1983-2019 period, the wealth ratio more than doubled, from 131.4 to 273.8. However, inflation by itself cut the wealth ratio by about a third from 131.4 to 88.6.

The middle class make out like bandits from inflation. Why is it apparently so opposed to inflation? Inflation also lowers wealth inequality and boosts real wealth growth, both mean and particularly median. Why does the Fed keep trying to squelch inflation? The reason is that people tend to feel the income effect of inflation but are not aware of the wealth effect. From a psychological point of view, people do not see the effect of inflation on their balance sheet. If they did, they might urge the Fed to promote inflation rather than dampening it. What about the recent drop in inflation? It’s bad news for the middle class.

See original post for references

As Yves said, you’d have to monetize your wealth for this to matter. Most people, like me, don’t want to sell their homes, so inflation just sucks. I know a ton of people who would love to cash in on the increased value of their home, but they’re too reluctant to move or downsize.

I would hardly call this “making out like a bandit”.

Wouldn’t the increased value of someone’s home be matched by the equally increased value of everyone else’s home? If so, the home seller would only have enough money to buy another home anyway, so what has the home seller gained? And if the home seller had to pay out any of the sold-home’s money to anything other than the next home, the home seller has lost the amount of the other-than-new-home payout.

And if the rich and the filthy rich and the Pirate Equity Funds are bidding up the prices of homes beyond what the newly home-sold home seller can pay with his or her fistfull of freshly home-sold dollars, then the new home-seller has fallen down and backwards.

Unless the homeseller takes a California-sized fistfull of dollars and buys a home with it in Dismal Seepage,Tennessota.

That’s just my layman’s thoughts on the matter, of course.

I think that once one gets older one downsizes, sometimes into assisted living, which is another racket that soaks up lots of cash. So the upper middle class, which has boosted their home values by manipulating zoning, et cetera, eventually loses out to the very wealthy who own the assisted living facilities.

But some upper middle class people simply downsize into smaller houses, which leaves them with cash with which to invest, travel, or spend.

The trouble is that, in counties like ours, no starter homes will ever be built again. The city council in my affluent town has slapped an $18,000 ‘impact fee’ on new houses ($12,000 for apartment units). They want to discourage people who aren’t loaded from coming here, which is to say, they don’t want to educate the children of low income people. Without these starter homes for people who want to move up, eventually the upper middle class won’t have anyone to sell their big homes to. All Ponzi schemes fail in the end.

“…A simple example can illustrate this point. Suppose a person holds $100.00 in assets and has a debt of $20.00. Her net worth is then $80.00. Suppose inflation is running at 5% per year and the value of her assets also goes up by 5% over the year. Then, in real terms the value of her assets remains unchanged over the year. But what about her debt? In real terms her outstanding debt is now down by 5% and the real value of her net worth rises to $81.00 (100 – 20 x 0.95)…”

Maybe the writer is describing a diffferent kind of debt than what I’m thinking about. I read the example and either missed or didn’t see any reference to the interest charged on debt. It’s not clear if or how that’s being included in the calculation. The paragraph above makes it sound like a $20 debt remains $20 over time if not paid off. And everybody doesn’t get the same interest rate for the same things they want a loan for.

There’s still alot of assumption that the benefits of ultra low rates for loans/credit (when they occur) trickle down in a major way to masses of the non-wealthy.

Again, we are experiencing an unprecedented increase in real home prices. Possibly the point is to borrow continually against this increase in home price but inflation will have meant other prices have risen correspondingly. I fail to understand Edward Wolff’s argument:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=YrNn

January 30, 2020

Share of Total Net Worth Held by Top 0.1%, Top 90 to 99% and Top 50 to 90%, 2020-2023

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=YrNt

January 30, 2020

Share of Total Net Worth Held by Top 0.1%, Top 90 to 99% and Top 50 to 90%, 2020-2023

(Indexed to 2020)

“The middle class make out like bandits from inflation.” Really? I’ve never heard this argument before.

“Why is it apparently so opposed to inflation?” OK, now I get it: the author is probably part of Uncle Joe’s cheerleading squad, keen to boast about the USA’s Goldilocks Economy but puzzled as to why Uncle Joe’s polling numbers are so lousy. Must be due to the ignorant USA middle class (or at least what’s left of it) failing to appreciate the brilliance of economic geniuses like himself (he is a professor at NYU) and the cool competence of the current man in the White House. I suppose if one tortures the numbers to death, one can advance an argument that a constant and predictable 5% inflation benefits a certain contingent of middle class people under certain limited conditions. But otherwise the professor’s argument is a stretch.

My view is that poor people suffer relatively less from inflation (they have nothing to lose and live paycheck-to-paycheck in any case), and that rich people benefit the most (the wealthy own hard assets that hold their value and can be used as collateral to take out loans that are repaid using depreciated currency, said loans being used to buy up more hard assets, wash, rinse, repeat…..). The middle class gets absolutely shafted. That is what I saw living in high-inflation 1990s Russia. Of course the USA’s present rate of inflation is not anywhere near what Russia suffered back then, but once inflationary expectations become embedded in people’s minds, they become hard to eliminate. The toothpaste can be put back into the tube, but only with difficulty.

Free of charge: a classic book on what inflation does to a society, “When Money Dies” by Adam Fergusson:

https://archive.org/details/when-money-dies-the-nightmare-of-deficit-spending/mode/2up

Germany’s middle class in the early 1920s certainly did not make out like bandits from inflation, and contrary to Professor Wolff I don’t think the USA’s middle class is doing very well either.

The Mexican inflation from the late 70’s to the early 90’s was really the catalyst for the immigration to the USA, where presumably the emigres made out like bandits, lowering American wages in the bargain.

Would that be an earlier wave than the further millions who came here as part of the Economic Cleansing of the Naftastinians?

The SoCal I knew as a kid tended to have 2nd and 3rd generation Mexican-American immigrants, fairly well established in places such as La Puente, not far from where I grew up.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Puente,_California

And then over the course of a dozen years, the Mexican Peso became worth 1/264th its previous value against the almighty buck, turning the spigots on the Great Remittance, droves of I daresay economic emigres, and whereas you would only see Mexican immigrants in the border states previously, presto change-o! they are now everywhere.

Their brand of hyperinflation was tame compared to Argentina or ye gads Venezuela.

It went from 12.5 Pesos = 1 $, to 3,300 Pesos = 1 $ and it was nothing compared to Weimar-the amounts, but the withering of wealth on the vine must have been something.

Let’s say you were middle-class in Mexico-an electrician, doctor, business owner, carpenter, or what have you, and had 100,000 Pesos in the bank and it was worth $12,500 US in 1978, and you just left it there, and 15 years later it had the buying power of $30 US. The wreck of their savings economy being even worse than Weimar, as that epoch only lasted a year or so, compared to the tyranny of distance in Mexico.

Inflation would fall softly on the lower classes if wages matched inflation, but that’s not what we’ve seen for lower-class wages. Now paychecks mean less but rent is still up, groceries are still up. And given that these are basic expenses, it becomes a lottery for homelessness among the working poor as they compete for dwindling welfare.

If you had a fixed rate mortgage you sure did.

I remember the old Bob Brinker weekend radio show from 30 years ago. Someone would call in to ask if they should pay off their very low fixed rate mortgage early. He said, if you call your bank with that question expect a free limo ride from the bank to complete the paperwork ASAP.

Well, my City and possibly it’s employees are benefiting from inflation as evidenced by the leaping home assessment values and corresponding real estate taxes. I was motivated in 2023 due to surging tax increases to put on excel the assessed values of my home and about 20 neighbors for the prior years. Turned out my 1587 square foot home matched the smallest homes yet had the highest accessed values of all homes I put to excel, while a much larger well apointed home stood out like a sore thumb being accessed much lower, as did all others to lesser extent. I won an abatement. But 2024 accesments just came out – I was spared probably because they still remembered me and the pointed and fact supported questions I put to excel. HOWEVER…almost every other home have at least 20% valuation increases for this tax year 2024. Combined with a 7% reduction in the tax RATE, that means I estimate about a 12% increase in taxes generally. Revenue wise I can’t see how my City isn’t making out like a bandit.

I tried to read the article but my desk lamp kept flickering on and off. / ;)

Wouldn’t the calculations change when predatory and subprime lending are part of the equation?

Not really. Another example: If you buy a $100,000 home for all cash and prices increase 10%, you’ve “earned” 10% on your money. If you buy the same house with 10% down and $10,000 in payments, and prices rise 10%, then you’ve made 50% on your money. Of course this ignores all the messiness of commissions, closing costs, loan points, etc. but the principle of leverage remains the same even with those factored in.

Note: if prices recede 10%, then the all-cash purchaser lost 10% on his money, and the borrow-to-purchase guy lost 50%.

Inflation favors borrowers if only because they pay usually fixed payments with money that’s worth less. Deflation favors creditors, which is why less-than-optimum vulture capitalists like the late Pete Peterson lobbied for “fixing” national debt.

Wealth is created in only a few ways: farming, ranching, manufacturing, mining, fishing, hunting, and inventing. Thats it. Everything else is wealth transfer.

This is mainly achieved through government and banking.

File “inflation helps the middle class” in the dustbin of inane orwellian language as “war is peace” and “slavery” is freedom.

Assuming all middle class people own their homes and in areas where they’ve appreciated faster than taxes, maintenance, home insurance, etc. Also, assumes people have increased wealth in non retirement accounts. Also, such economists seem to assume that middle class folks don’t use Quicken or Excel and can’t figure out on their own the impacts of inflation on their budgets. Also, this particular “Economist” appears to be 77 yrs old. Part of generation that had the potential to buy a property for $15,000K and sell for over $850K like my parents did. I can see how that kind of inflation might be appealing to certain “middle class” groups. If people such as this are brought out later in the year to cheerlead for Biden it will likely have the opposite effect than intended.

The common ‘homeowner=middle-class’ distinction is class analysis once removed, at least. Class is about ownership, specifically of the means of production. I like to advance the idea that, in a deindustrialized/financialized/fictionalized economy, what is produced is wealth, and the means of production are assets. So, the common distinction is a simplification, but has merit in this framework.

Trouble is, homeownership rate in the U.S. lags behind not only the socialist and post-soviet economies, but most of the developed world. It’s around 62% (and we’d have to account for avg. household size), and on a general downward trend. Basically, if US policymakers want a W. Bush style ‘ownership society’, they can’t pretend to represent both the interests of the super rich, the banks, and big real estate, at the same time as those of a suburban homeowner; they can’t pretend there is no such thing as class, or that we’re all middle class, or will be.

In addition to the above critiques, my twenty bucks worth: (two-cents adjusted for inflation)

The author sounds like Paul K., typical “assume a can-opener” neoclassical junk economics. The internally-valid tautology offered makes sense in that regard, however has little relation to empirical reality experienced by average US folk.

The “middle class”? Who cares about the working-class, the poor, or the vast majority of the population?

The (upper) “middle class” make out like bandits, the rest get price-gouged, extorted and reduced to debt peonage. The term middle class itself is politically loaded. As Yves points out the “median income” covers over a lot of garbage as well.

For millions upon millions of US denizens, both asset price inflation, and more recent consumer price inflation are devastating. So-called health care costs are a great example.

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/jan/11/hospital-debt-increase-people-with-insurance

So the UPPER Middle Classes make out like bandits, while the rest get extorted. And then there is the monopoly price-gouging, market abuse, and rent-seeking, but that is ignored by the author.

Folks have to sell their primary residence to pay the ever-rising health care extortion. How wonderful for them.

No wonder Steve Keen and Michael Hudson call it Junk Economics.

The great irony is that middle class is working class, as they still work (although not manual labor) in order to feed and shelter themselves and their kin.

But they are made to believe themselves part of the owner/rentier/capitalist class by having enough spending power to hire others to do tasks for them.

The day that middle class realize they are not part of the owner capitalist class, like you mention, and they’re just a teeny tiny better than the working class, that’s the day we will have the revolution.

.

It can’t come soon enough.

The upper middle class is what Richard V Reeves discussed in ‘Dream Hoarders’. I thought this meant the upper 9.9% in income, but the review I’m posting below says top 20%. Most, though not all, of my friends from college and grad school fall into the latter income category or are close to it. Friends from high school are more diverse.

The problem in a nutshell, imo, is that the upper middle class is the class that benefits most from high home prices. Government caters to them, because they run government. When it comes time to vote, they punch over their weight, because they organize. For things to get better for non-homeowners, the upper middle class will have to have their home investments decline precipitously in value. I’m not holding my breath.

I’ve long contended that the upper middle class manipulates the public education system, k-12 through college, so that their kids benefit at the expense of others’ kids. I can speak only for my state of SC, but their kids are far more likely to receive state scholarship money because there are five levels of a given class, and the upper middle class parents lobby for their kids to get into the upper levels, which receive greater weight when grades that impact scholarships are determined. Lower middle class parents don’t know to do this.

https://www.educationnext.org/the-rich-get-richer-book-review-dream-hoarders-richard-v-reeves/

In America where the new “middle class” doesn’t own bonds, doesn’t own stock, doesn’t own a home, and has less than $400 in “liquid assets” to cover an emergency? WTF?

Every time I think an economist “scientist” has drained all the water out of the pool, one of them comes along and manages to prove me wrong. Put guys like this in charge of airplane companies and what do you get – doors flying off in mid air. But no, better yet, lets just let them say how the whole American economy should be run.

The article was clearly written with Bill Ackerman in mind, using Larry Summers principles, economic and otherwise. Though in fairness, it achieves its goal: obfuscation after reading a few lines….

The author ought to ask Argentines what they think about inflation.

And the people in Turkiye as well. This article really belongs to the “just kill me already” category.

What is this thing called “the wealth effect”? Is it some kind of immutable law observable in the real world? Or is it largely nonsense conjured up by economists out of nothingness?

” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wealth_effect

The wealth effect is the change in spending that accompanies a change in perceived wealth. Usually the wealth effect is positive: spending changes in the same direction as perceived wealth. ”

Inflation has been continuous since 1990, but so far as I can tell there has been no important wealth bolstering effect from inflation as such on the middle class over the period.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=19VMC

January 30, 2018

Share of Total Net Worth Held by Top 0.1%, Top 90 to 99% and Top 50 to 90%, 1990-2023

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=19W5X

January 30, 2018

Share of Total Net Worth Held by Top 0.1%, Top 90 to 99% and Top 50 to 90%, 1990-2023

(Indexed to 1990)

I do wonder if this is what makes credit cards so insidious.

As long as one can manage the monthly minimum one have a perceived spending power at a multiple of what one would have based on cash in hand alone.

The so-called wealth effect can prove to be a double-edged sword as what happened during the run up to the housing collapse during the early years of the Obama administration when many people took cash out refinancing of their home mortgages thinking housing prices only increase. When housing prices collapsed they owed more than their homes were worth. So much for the wealth effect.

Anything to keep peoole from coming to the conclusion that it’s the asset bubbles that need to be popped to fight inflation.

ding ding!

and there it is, a gelatinous mass, quivering on the floor.

whole thing read like a brochure, to me.

for continuing to believe real hard that asset inflation is somehow good for te middle class.

when they are more than likely to actually live in their greatest asset(often overinflated, and often tickytacky bs that aint worth what they paid for it…per my brother in Kingwood, Texas)…and, in texas at least, to pay higher property taxes for that asset inflation.

i say burn it all down and start over.

but the “assets” of the uber rich must be burned, as well///or it just aint gonna work, and we’ll hafta eat them instead.

so, it seems to me that our betters(sic) have a choice,lol….

reset, per Hudson…or become food.

this will seem less extreme, over time….at least to the non-uber rich.

A. what is a asset bubble.

B. Due to decades of ideology everyone has been forced into deriving income from investments, not just wages e.g. hyper individualism w/a side of pay to play and self reliance in a market place society. Hence sharp sudden deflation would wipe out the little people first and foremost, Capital would take a hit but could weather the storm and buy everything up on the cheap, not to mention increase its political power.

C. Maybe why big Cap Corps are always bailed out … cough … national security … cough …

This all runs quite contrary to what I was told back in 1978 by a fellow whose family had a football stadium named after them and who owned his-and-her airplanes. He swore that it was easy for a rich man like him to beat inflation while it was hard on the wage earner.

Perhaps he protested a bit too much.

“What causes households and investors trouble is not inflation but changes in the rate of inflation, typically increases. If the US had, pick a number, 2%, 3% or even 4% inflation, and it varied by only 0.5% in either direction over a year, businesses, labor negotiators, households and investors could plan with a bit of a degree of certainty.”

Makes me think of Steve Keen’s “change in the change of debt”, where even a slight slump in the rate of new debt being created can have massive reverberations.

Inflation benefits the ruling class that can borrow huge sums of money for next to nothing and create arbitrage from interest rate differences from the capital that sits in various markets. It’s literally designed for that purpose, strictly, so the bond market and interbank lending is always liquid, due to the fact the debt burden is lessened over time, and allows for low IRs. A deflationary market would by nature create high interest rates.

But the real meat of the issue is that inflation isn’t set. It is attempted to be set. But this attempt is just that. Yves states 2 or 3 or 4. Well reality is more like 5%. For the last year it was in reality about 15%, the CPI posted by BLS is completely falsified through various variable shenanigans and is often revised (many months later) once the news cycle passes. The avg wage earners wage grows by 3%. So essentially every avg wage earner is sliding backwards on avg of 2% purchasing power yoy. And we can see this is true by looking at inflation adjusted wage with actual inflation (as opposed to 2% target rate) that shows purchasing power of the lower 80% falling almost linearly from the 70s to today.

So to assume that, in general, inflation is good is super silly and only exists in the minds of economists that really don’t have a grounding in reality.

Inflation, historically, punishes those who do not have assets like real estate fortunes, precious metals, businesses, large stock and bond portfolios, etc. Just in this sense, one can immediately see that it is immensely harmful to the middle and lower classes. One can think of inflation secure assets as having a minimum buy in. Say that number in America is around $1 million today. Inflation essentially annually raises this minimum buy in making it harder and harder for the avg family to ever gain financial independence. A single year of 15% is disastrous. No one to my knowledge has anywhere close to a 15% growth in income. In fact, almost every wage earner including high income wage earners has been losing the battle. This includes doctors, lawyers, etc. Most cap out at some amount, meaning, say a decade before retirement most will have reached a ceiling meaning their purchasing power to income ratio will constantly fall for the last decade of their career. This is where 401ks, etc. are supposed to start accruing. The issue the US now faces is if the inflation, which historically averaged around 5%, begins to approach the stock market avg returns of 7%, it’s game over. And honestly it has been game over for a while now.

Anecdotally:

I made around $250k 10 years out of college, which happened to be right around 2021. That $250k was, after taxes, the insurance, etc. about comparable to the $125k I made 5 years out of college. Meaning I’ve doubled my wage in 5 years, but my purchasing power and hence my ability to invest more has flatlined. And I’m lucky, have no debts, have inheritance, etc. I honestly can’t imagine how the avg family survives in a high cost state like California. The inflation experienced by Californians has gotten so disgusting, it’s lead to huge outflows to Texas. That is, in essence, inflation has decimated the middle class (that almost barely exists anymore) and caused mass migration to survive economically. People usually don’t move for no reason, and virtually every single friend in my generation (millenial) laments how the bar to owning a home, financial security, etc has literally been raised over and over again to the point that keeping up with it is unnattainable. No one can simply double their income, try finding a job that earns $500k/yr. They barely exist. But housing has doubled in the last 4 years. Avg car went from $38k in 2019 to $55k in 2023. My electricity bill went from $200/month in 2019 to $750/month today.

File under … mobile labour and first mover advantage theory …

The position that the middle class is making out like a bandit just proves crime doesn’t pay.

What drivel…

I’m less hostile to Wollf’s premise than many here appear to be insofar as this squares with my understanding that inflation favours debtors and hurts lenders — isn’t the former group generally poorer than the latter?

When IR goes up its a game of pass the proverbial buck eg. It all has to be broken down line by line on everyone’s balance sheet where income and outgoings meet reality.

The poor always lose as they have no assets or balance sheet = day to day or week to week income with no future guidance.

Higher IR, especially when its increased hard and sharp hits C/RE sorts hard and they will increase rents/leases to cover it = feed back loops.

Shrinking of the so called middle class makes matters worse as post pay to play has only increased their out goings in life or family formation = increased immigration = rim shot.

This might be why the PMC is circling its wagons, we made it, better genes, individual social status is at late Rome stage thingy. Not that the vulgar GOP has a problem with any of it but they have always been at war with the Dems and is now a spectator sport with the winnar* getting more political funding …

One thing I never see covered on NC, is how to protect your wealth and plan for retirement, ethically – in the face of inflation over decades.

I am not putting money into a retirement fund (I can’t find one that is ethical or which does not have terrible returns), I am not investing the money I have to protect it from (recently significant) inflation (same problem: where to put it ethically), I don’t have a plan for what to do with my money either (I don’t have the time to research and figure this out) – and I would never trust a financial advisor (nearly all commission based, and my parents got burned by dodgy investments they were talked into, which my cynicism likely makes me immune to).

It’s a nice/first-world-problem to have – what to do with excess money – but what can I do when every option I look at appears to be ethically compromised?

In Ireland where there is a housing crisis, I am seeing the finance industry successfully get victims of the housing crisis to buy-in to keeping house prices high (i.e. to permanently ensure there is a housing crisis with not enough houses built), simply by pointing out to people that the pension fund their work auto-enrolls them into (and which they never look at the fineprint of to see what they are invested in) is invested in real estate funds exploiting the housing crisis – and the finance industry is even convincing housing crisis victims who have had to take out a massive mortgage, to buy-in to keeping house prices high so they don’t go into negative equity, so that they aren’t prevented from getting a second mortgage later to move out of their ‘starter home’ and into a better one as their family grows etc..

So on the one hand the average member of the public who appears to not give a toss what they are invested in, is able to have a successful retirement fund and stuff – and the upper-middle class tech types that can afford a mortgage in places like e.g. Dublin are able to sell-out and begin supporting a continued housing crisis to suit their personal financial interests – whereas I am kind of paralyzing my financial future (even my financial present due to inflation) by only being able to see unethical investments and refusing to have anything to do with them, and not knowing what I should do with my money as a result.

It would be interesting to see NC write something that deals with navigating this ethically. I know folks here (writers/contributors too) need to think of and deal with these things as well – so I would be interested in seeing how much people have chosen to personally ethically compromise as well (which I wonder if that’s maybe why it isn’t written about much, from a personal point of view).

If you get really puritanical, you think of Michael Hudson’s frequently mentioned term of ‘money making money’ as the root of most financial evils – and it’s almost hard to see how any type of passive investing can be ethical at all – so I want to know where people + contributors/writers here draw the line, including personally for themselves.

I hate to tell you but I do not think there is an ethical way to invest. Perhaps you can find a local business that has significant employee ownership and has a do-good mission of sorts, as in an enterprise in the spirit of Mondragon. However, you would have the risk of lack of diversification.

Ex that type of company, capitalism is based on exploitation of labor, resources, and in its current incarnation, efforts to evade regulation, taxes, disclosure, and game accounting.

I am also personally poorly suited to take up this topic due to a deep-seated, visceral dislike of publicly traded stocks, since they allow executives and board members to control valuable and often societally important enterprises with very little in the way of transparency or accountability, as reflected in ludicrously indefensible levels of executive and board pay. My first full time job was working on new stock and bond offerings at Goldman, back in the stone ages when Wall Street was criminal only at the margins. Even then, seeing how stock sausages were sold in a comparatively clean era was enough to make me regard them as wholly speculative. As business school professor Amar Bhide has described longer form, equities are a very weak and legal ambiguous promise, and are not suited to be traded on an anonymous, arm’s length basis. A company would have to make extensive disclosures about its plans and current operations for a stock investor to make an informed decision. The company can never do so because it would inevitably disclose valuable intel to competitors.

Bonds are generally not ethically problematic and are also vastly better legal promises. But I assume you are seeking higher returns.