Yves here. This article comes to a general conclusion that could surprise only an economist: that people in the real world very much loathe changes to their living standards, whether inflicted by inflation or a economic downturn (loss jobs or hours worked, lower bonuses, lower company income). But the part that might surprise even non-economists is how great this business cycle aversion is, reflected below in how much survey respondents are willing to give up to escape them..

This finding also explains what a train wreck the Trump 2.0 presidency is set to be. Trump is an uncertainty generator, which wreaks havoc in terms of commercial and personal planning. For instance, pretty much everyone I know who is a bit long in tooth is now worried about Social Security. This has all sorts of knock-on effects, from everything to making investments to small splurges like a nice vacation. So Trump is going to directly dampen GDP via his wildly unstable behavior.

By Dimitris Georgarakos, Kwang Hwan Kim, Olivier Coibion, Myungkyu Shim, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Geoff Kenny, Seowoo Han, and Michael Weber. Originally published at VoxEU

How costly are business cycles and inflation? This column reports on a survey that asked consumers across 13 countries how much consumption they would be willing to sacrifice to eliminate business cycles. Contrary to the prediction of standard macroeconomic models that business cycle fluctuations are close to costless, consumers reported that they would give up around 5% of their consumption. This is of the same order of magnitude as what they would give up to bring inflation to their desired level.

Imagine a world where macroeconomic ups and downs don’t disrupt our lives. No recessions that put your job at greater risk, no skyrocketing prices, no financial crises, etc. Sounds ideal, right? But how much would you be willing to sacrifice to make that a reality?

Macroeconomists have long been interested in measuring the costs of business cycles and inflation, estimating the effects of macroeconomic volatility and uncertainty on firms and households (e.g. Bloom et al. 2022, Yotzov et al. 2022, Gorodnichenko et al., 2022, Bachmann et al. 2024), and quantifying how large the gains could be to consumers from eliminating them. The consensus view based on standard macroeconomic models (Lucas 2003 provides an extensive review of this topic) is that households should not be willing to sacrifice much to eliminate business cycles and that inflation is much more costly. In a recent paper, we took a different approach (Georgarakos et al. 2025). Rather than relying on what theory predicts about this willingness to pay of individuals, we surveyed consumers across 13 advanced economies to see how much individuals report they would be willing to sacrifice in terms of their lifetime consumption to eliminate either economic volatility or inflation. Here’s what we found.

Key Findings

- People are willing to give up 5-6% of their lifetime consumption to eliminate economic ups and downs.

- They are also willing to sacrifice around 5% of their lifetime consumption to achieve their preferred inflation levels.

- These figures are much higher than what traditional economic theories suggest.

In other words, while past research has suggested that stabilising the economy wouldn’t make a big difference in terms of welfare, our study finds that real people think otherwise.

Why Do People Care So Much About Business Cycles?

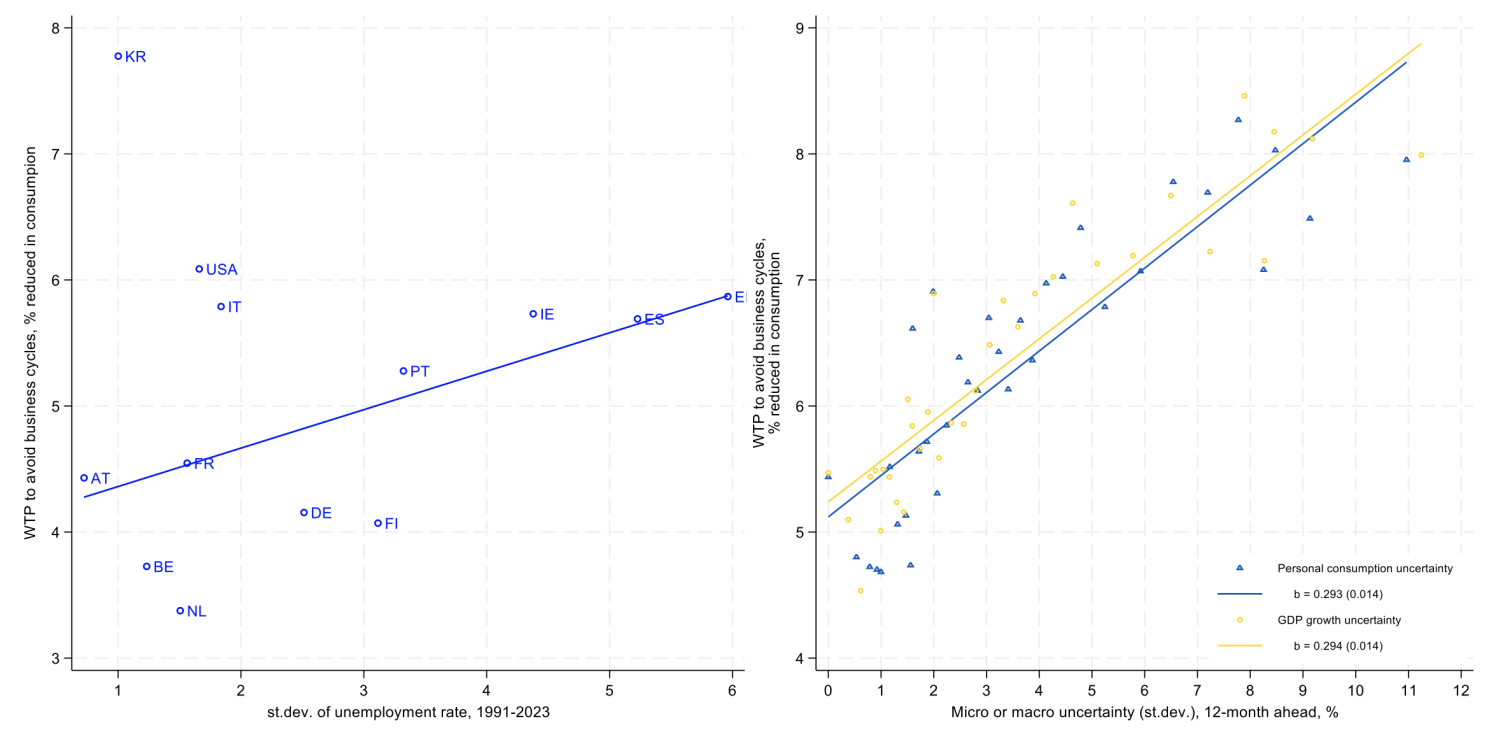

We found that several factors are particularly important in determining how much people would be willing to pay to avoid business cycles, as illustrated in Figure 1.

1 Personal experience with macroeconomic volatility

People in countries with historically volatile economies are willing to pay more. In our sample, Germany and the Netherlands are the two countries with the lowest macroeconomic volatility over the last 30 years, and consumers in those countries report that they would sacrifice around 3-4% of their consumption to eliminate business cycles. In the two most volatile countries in our sample, Spain and Greece, consumers would be prepared to sacrifice almost twice as much to eliminate business cycle risk.

2 Cyclicality of consumption and income

Individuals whose spending and income are more sensitive to changes in the state of the economy feel the effects of downturns more. As a result, we would expect them to be willing to sacrifice more to avoid instability. We find that this is indeed the case. Because of the different types of jobs and assets that people have, there is remarkable variation in the extent to which people are affected, either positively or negatively, by business cycle fluctuations. The US, for example, is one of the countries in which people’s incomes are the most sensitive to business cycles, and US consumers correspondingly report some of the highest willingness to pay (WTP) to achieve economic stability across countries.

3 Economic uncertainty

Our willingness to pay to eliminate future business cycles should also depend on how big we think those future cycles are likely to be: those who foresee very little economic volatility in the future should not be willing to pay nearly as much as those who expect to see large swings. We find this to be one of the main determinants of people’s WTP to eliminate business cycles. Across countries, as shown in Figure 1 below, an increased variability in the unemployment rate is associated with a higher willingness to pay. Moreover, higher micro or macro uncertainty is also associated with a higher willingness to pay at the individual level.

Figure 1 Determinants of the willingness to pay to eliminate business cycles

There are many other factors that matter as well, but quantitatively, we found these three explanations to be some of the most important when it comes to eliminating business cycles.

What About Inflation?

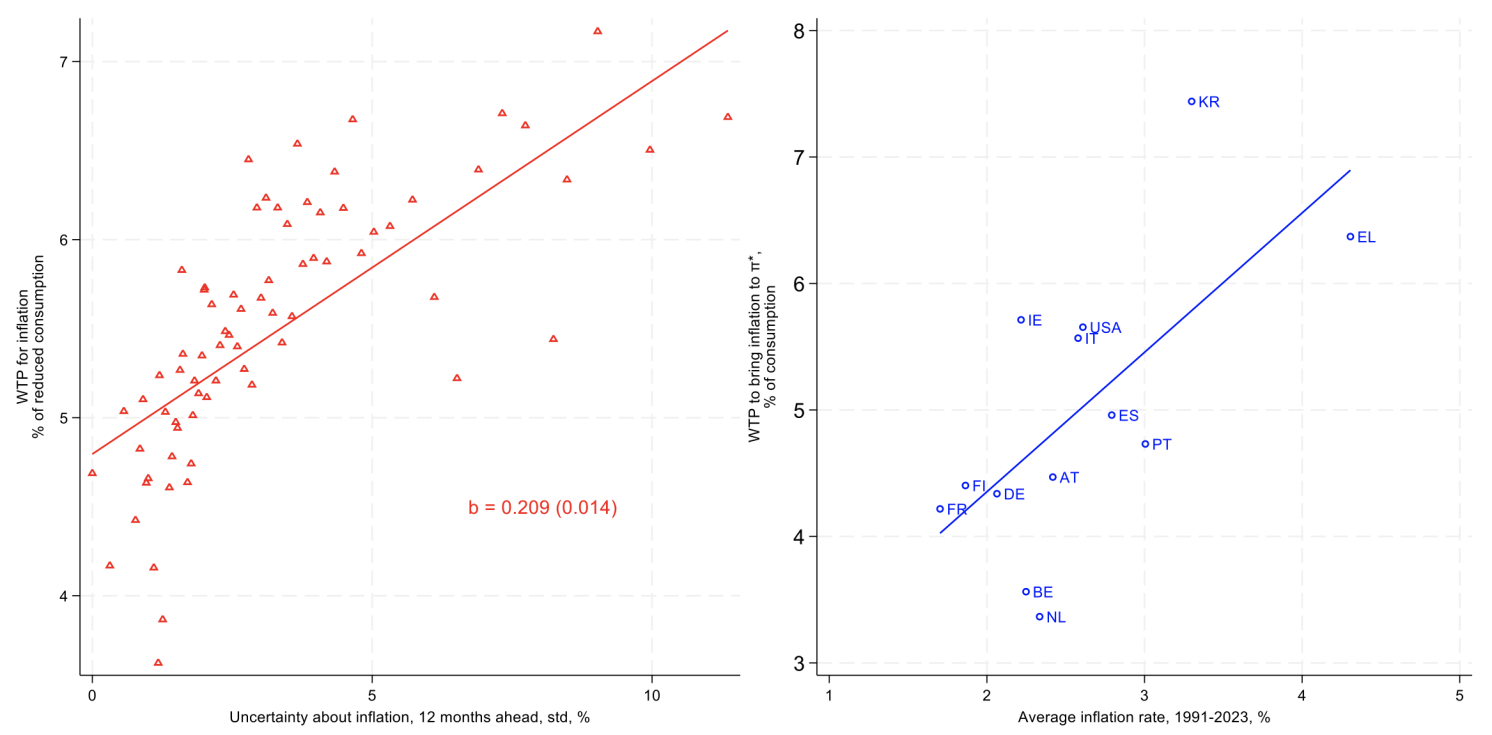

For inflation, we wanted to know how much people would be willing to sacrifice to see inflation reach the ideal level for them. What inflation rate would that be? We found that people wanted to see prices fall overall, and by pretty large amounts. Part of this desire for falling prices was to offset the perceived price increases during the inflation surge: people living in countries where prices went up more in recent years generally wanted to see bigger price declines than those in countries who experienced more moderate inflation.

But just because someone would like to see prices fall, that necessarily doesn’t mean that they would be prepared to sacrifice much to achieve that outcome. So we asked survey participants how much they would be prepared to sacrifice to achieve their preferred inflation target. The answer was again close to 5% of their consumption, on average.

Why so high? One reason is that people want to see large changes in the inflation rate. As shown in the figure below, people living in countries where inflation has been low are willing to pay less to reduce inflation, because they perceive a smaller decline as being necessary.

Figure 2 Historical inflation and the willingness to pay to reduce inflation

Another factor that helps explain a high WTP to reduce inflation is the fact that people associate higher inflation with more volatile and uncertain inflation, and the uncertainty about inflation is itself perceived as costly as shown in Figure 2.

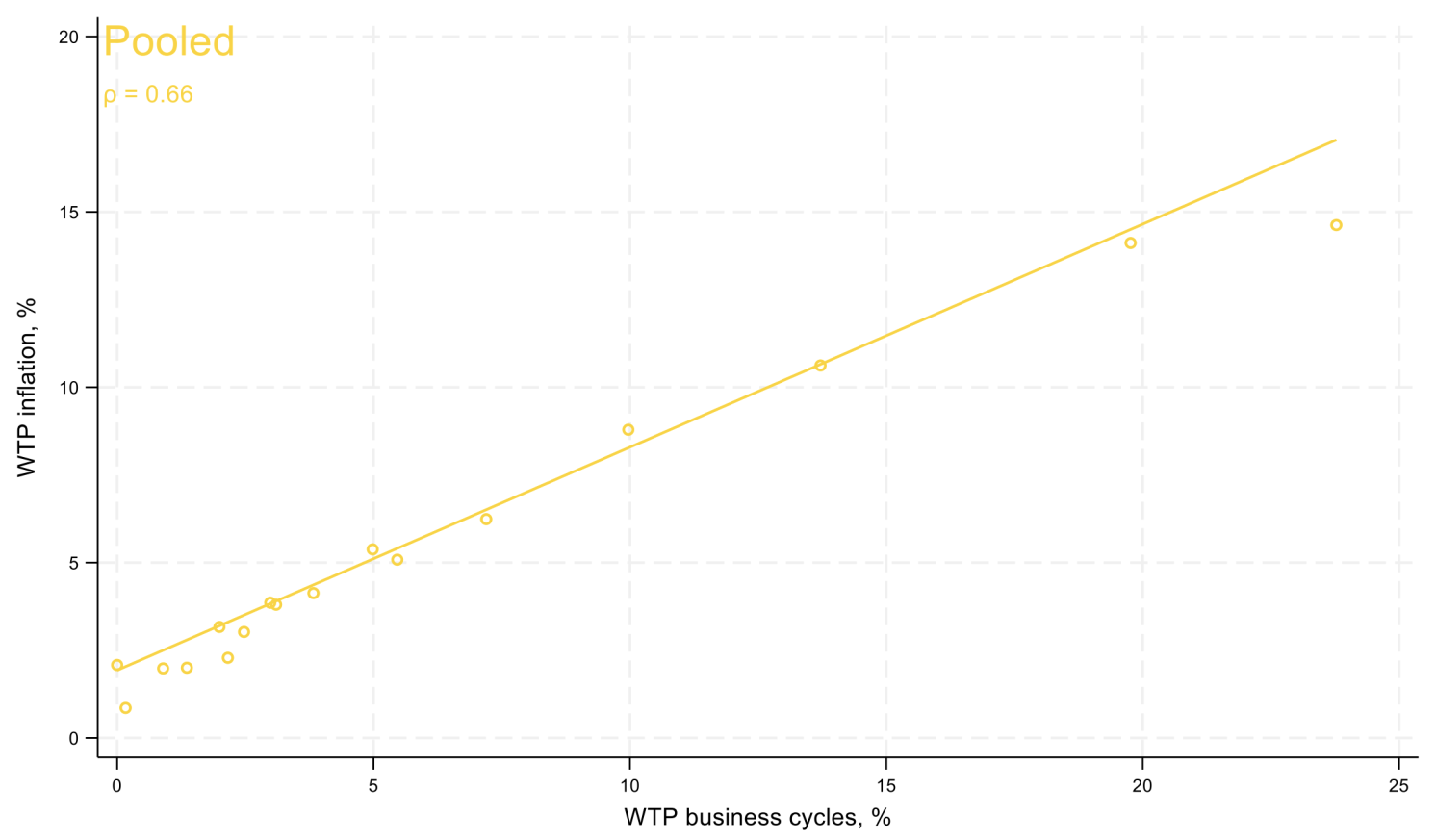

Finally, a third important reason why people are willing to pay so much to reduce inflation is that they seem to perceive higher inflation as happening when economic times are bad, so reducing inflation also serves to reduce business cycle volatility and vice-versa. Consistent with this notion, we find that people who report that they are willing to pay more to eliminate business cycles are also willing to pay more to reduce inflation, as shown in Figure 3. Even though macroeconomists view the long-run level of inflation and economic volatility as largely separate things, this is not how consumers perceive them, leading to a strong correlation between their willingness to pay for either.

Figure 3 WTP to eliminate business cycles vs WTP to reduce inflation

Implications for Policymakers

Traditional economic models often assume that people don’t worry much about business cycle volatility because they can ‘smooth’ their consumption over time – saving in good times and spending in bad times. But our study challenges that idea.

Instead, it shows that people strongly prefer a stable economy and are willing to give up a significant portion of their potential income to achieve it. This insight suggests that macroeconomic policies should align more closely with what people actually value, not just what economic models predict.

At the end of the day, economic stability isn’t just an abstract concept – it is something that affects real lives. Whether it is job security, price stability, or financial peace of mind, people are willing to pay a surprising amount to avoid uncertainty.

For policymakers, that is a message worth listening to.

Authors’ note: Ordering of author names is randomised. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the ECB, the Euro System or the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Economic cycles seem to be almost inevitable – the question is more whether they can be used as part of a positive process of clearing out the junk and investing in the new (such as happened with 19th Century railroads), or whether they just leave a mountains of tulip bulbs and empty internet domains in their wake. There is an arguable case to make that ironing out shorter term cycles simply makes the bigger cycles more intense in their destructiveness – China is helpfully trying to give us a live demonstration on whether this is true or not.

I strongly suspect that one driver of chaos in recent years is the dominance of a form of capitalism that requires intense and frequent cycles in order to profit – disaster capitalists if you prefer. I have no idea what is really going on with Trump, but the only real certainty is that at least some of the people behind the policies fully intend to profit from a rapid and deep recession and then (they hope) and equally rapid recovery.

Off hand I would guess that volatility enhances opportunities for looting.

I was listening to an analyst who is suggesting that Trump is deliberately trying to throw the economy into recession with budget cuts, tariffs, etc., to kill the inflationary pressures (especially on wages) and get the federal rates back down, then when everyone can cash out their record home equity with 5.5% HELOC’s things will come booming back for the mid-terms. Since Musk is the face of austerity, he can ditch Musk when it comes time to change the tune.

The first part seems to be consistent with the behavior (as much as anything), and the second part would make sense, if the first act doesn’t set off another financial crisis or other financial catastrophe. But I hesitate to pretend to “know” what is going on in Trump’s head in any particular moment, let alone enough to try to trace a line through each ephemeral moment to claim the existence of trend.

As one of those millennials that entered their 20s right when the Great Recession cratered everything, I think the authors are still missing the real point: path-dependence. Or for those of a surlier persuasion: the déclassé. From the individual perspective, an unregulated business cycle isn’t a cycle at all, it’s an event that reorders people’s social options permanently.

From that standpoint, I don’t think the desire for stability is even about smoothing out income and consumption. It’s a very personal desire for a life that still offers some sort of agency and freedom without the overhanging threat of sozialer Mord. I won’t get into my own personal details, but I see in myself, and many others my age or younger, how economic conditions have fundamentally changed us. And not in ways that will preserve the current economic system, society, or its supposed values.

A very important argument. There have been some studies of “wealth inequality games” — based on repeated rounds of acquisition and redistribution of wealth where chance plays a role. These simulations showed that a large initial endowment was decisive; those players without it could not afford to “lose” a round — they never caught up afterwards.

There were also socio-economic studies about the long-term impact of entering the labour market during a crisis. Basically, young people starting their work life during a crisis incur a disadvantage that they can never compensate.

Your remark about path dependency and getting effectively cut off from social and economic opportunities because of one of those sharp downturns (that cannot be withstood for a lack of wealth) is right on the mark.

I think the technical term for the long term damage caused by economic downturns is called hysteresis, and it’s very real.

All Ponzi schemes cause waste and enrich a few.

Fictional Reserve Banking is a Ponzi. Always was.

Only eCONomists miss this point! They are employed by the Ponzi.

If you are going to criticize, the onus is on you to be accurate. So you need to stop broadcasting misinformation if anyone is to take you seriously.

There is no fractional reserve banking. That’s based on the laanable funds fallacy. I will not approve any more comments by you propagating THAT fiction now that you have been warned.

And I’m not about to spoon feed you. You need to bone up.

“This insight suggests that macroeconomic policies should align more closely with what people actually value, not just what economic models predict”

Spoken like real, card-carrying economists!

Hard LOL.

I wonder where they stand on democracy etc, or if they’re agnostic of such political questions. They might also be surprised to learn people care about that too.

It little surprises me that economists might to have a very different perspective than ordinary people on what they call business cycles and inflation. Most people experience business cycles and inflation through their impacts on “job security, price stability, or financial peace of mind”. In contrast, I believe economists experience business cycles and inflation as abstract concepts which they can graph and mathematize to built pretty mathematical models — although I suppose business cycles and inflation might elicit a different analysis if they lead to pay-cuts or layoffs in the economics department.

“Contrary to the prediction of standard macroeconomic models that business cycle fluctuations are close to costless,” I grow worried there is a gathering storm of response to Trump 2.0.

Interesting article on what people are “willing to pay”, but I think that many of us who are willing to pay to be insulated from business cycles are already paying to protect ourselves from economic disruption whether it is business cycle related or due to a personal crises. The reason my husband and I have lived significantly below our means for 25 years is to save enough/have no debt to insulate us from economic distress when crap happens which it inevitably does.

In 2010, A military program was cancelled and my husband’s employer laid off almost 1/2 their workforce including him. We were okay for quite a while while he looked for a new job. (It took 4 months for a part-time job which converted to full-time after another 6 months).

In 2021, my parents needed help due to health problems, so I cut back to part time work for 2 years. We cut back our discretionary spending but were able to live ok with our saving cushion. I’m back to full-time now and building that cushion back up.

Our friends say we “live like church mice” because we don’t spend like they do. So we already pay in reduced consumption.