Yves here. We’ve described long form and repeatedly in our work in 2015 on the Greek bailout crisis why the Eurozone is a roach motel. It is impossible to leave without causing massive capital flight and banking system collapse due to the big reason that it cannot be done quickly or covertly. The lead times for even things like getting a new currency into circulation is much longer than Excel and PowerPoint jockeys imagine.

But this post offers a completely different set of observations: that there are also not-much-acknowledged advantages to European Union and even the Eurozone.

By Benjamin Born, Professor of Macroeconomics Frankfurt School Of Finance & Management, Luis Huxel, PhD student in Economics University Of Tuebingen, Gernot Müller, Professor of Economics University of Tübingen, and Johannes Pfeifer, Associate Professor at the Center for Macroeconomic Research University Of Cologne. Originally published at VoxEU

Recent events, such as tariff announcements, illustrate that even global shocks may feature important country-specific components. This column finds that a monetary union shapes the impact of economic uncertainty on its member countries by substantially mitigating the adverse effects of country-specific shocks. It does so by providing a nominal anchor that effectively eliminates price level risk arising from country-specific uncertainty. This finding also implies heterogeneous exposure to uncertainty can reduce the need for policy interventions at the country level, whether by the common central bank or by national fiscal policy.

The re-election of Donald Trump has led to heightened uncertainty in the global economy (Grzana and Ilzetzki 2025). The whiplash-inducing, erratic tariff announcements on and around ‘Liberation Day’ on 2 April 2025, are a perfect showcase. They triggered major turmoil in global financial markets (Benigno 2025).

Every Unhappy Country Is Unhappy in its Own Way

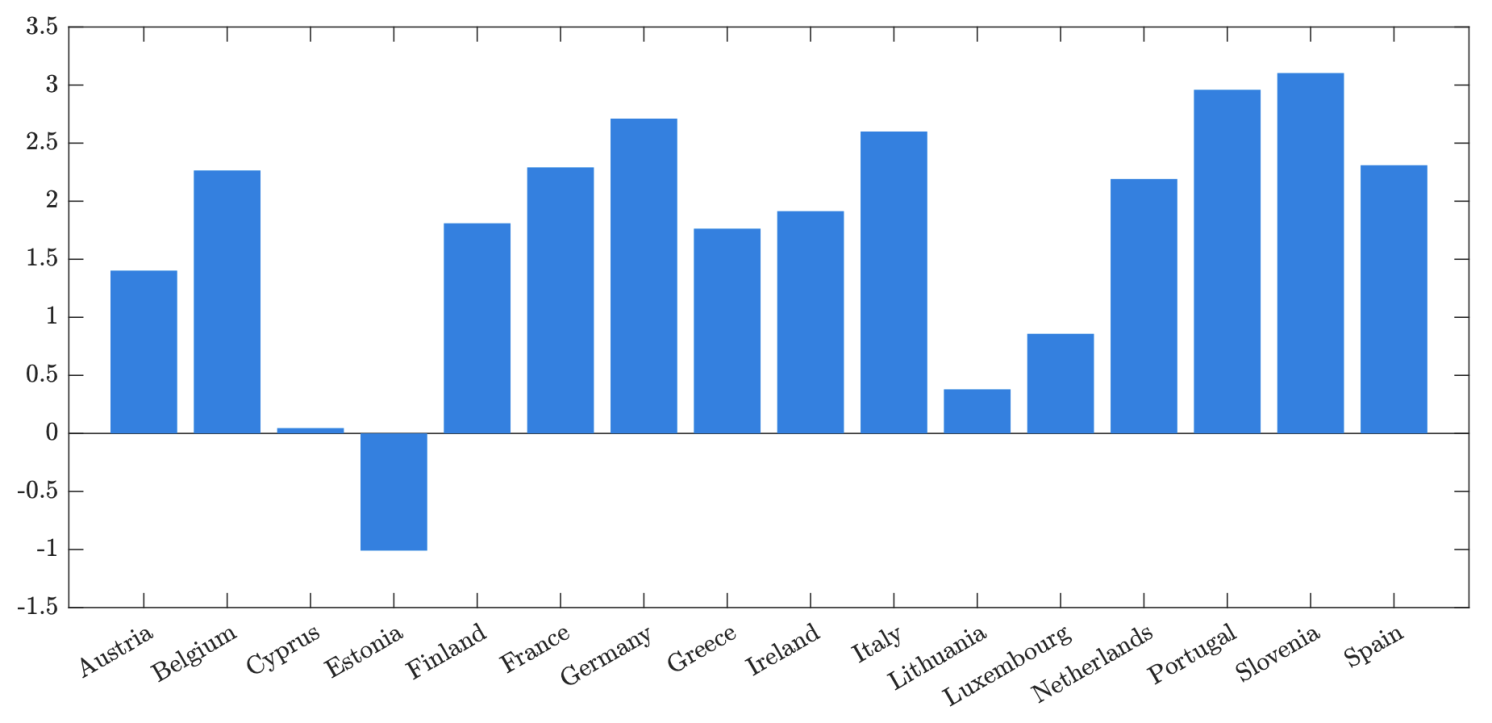

However, even a global uncertainty shock such as Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariff announcement does not affect all countries equally. Countries have varying exposures to international trade, especially with the US. Figure 1 illustrates, from the perspective of selected European countries, the unexpected increase in stock market volatility in April 2025 — a widely used indicator of economic uncertainty. Uncertainty in Germany, Portugal, and Slovenia surged by almost three standard deviations, an event only expected in 0.3% of all months. At the same time, the impact was less pronounced in Cyprus and Lithuania. Given that these countries share a common monetary policy within the euro area, one might be concerned that the absence of a country-specific monetary policy response could amplify the shock’s effects. Indeed, it is well established that uncertainty shocks can have particularly adverse effects when monetary policy is not responsive due to the zero lower bound (Basu and Bundick 2017). The same may hold true when the exchange rate arrangement prevents a monetary policy response at the country level.

Figure 1 Increase in stock market volatility in April 2025

Notes: Unexpected realised stock market volatility in April 2025. We estimate an AR(1) for the monthly realised volatility of the Datastream Stock Market Performance Index for each country. What is shown are the residuals in April 2025, expressed as standard deviations of the country’s residuals.

In new research, we show that this conjecture is wrong (Born et al. 2025). We investigate how economic uncertainty affects euro area (EA) countries compared to countries with flexible exchange rates and find that while the impact of common uncertainty shocks is comparable in both country groups, the impact of country-specific uncertainty shocks is weaker in euro area countries, not stronger as the received wisdom would suggest.

Evidence from 30 Countries

We analyse quarterly data from 17 euro area members and 13 countries with floating exchange rates over the period 1999–2022. Using a structural Bayesian vector autoregression (BVAR), we estimate the effects of uncertainty shocks based on two measures of economic uncertainty: realised stock market volatility, following Bloom (2009), and the forecast error-based uncertainty indicator developed by Jurado et al. (2015), compiled by Comunale and Nguyen (2023) for euro area countries. Importantly, we identify both common and country-specific uncertainty shocks within the BVAR.

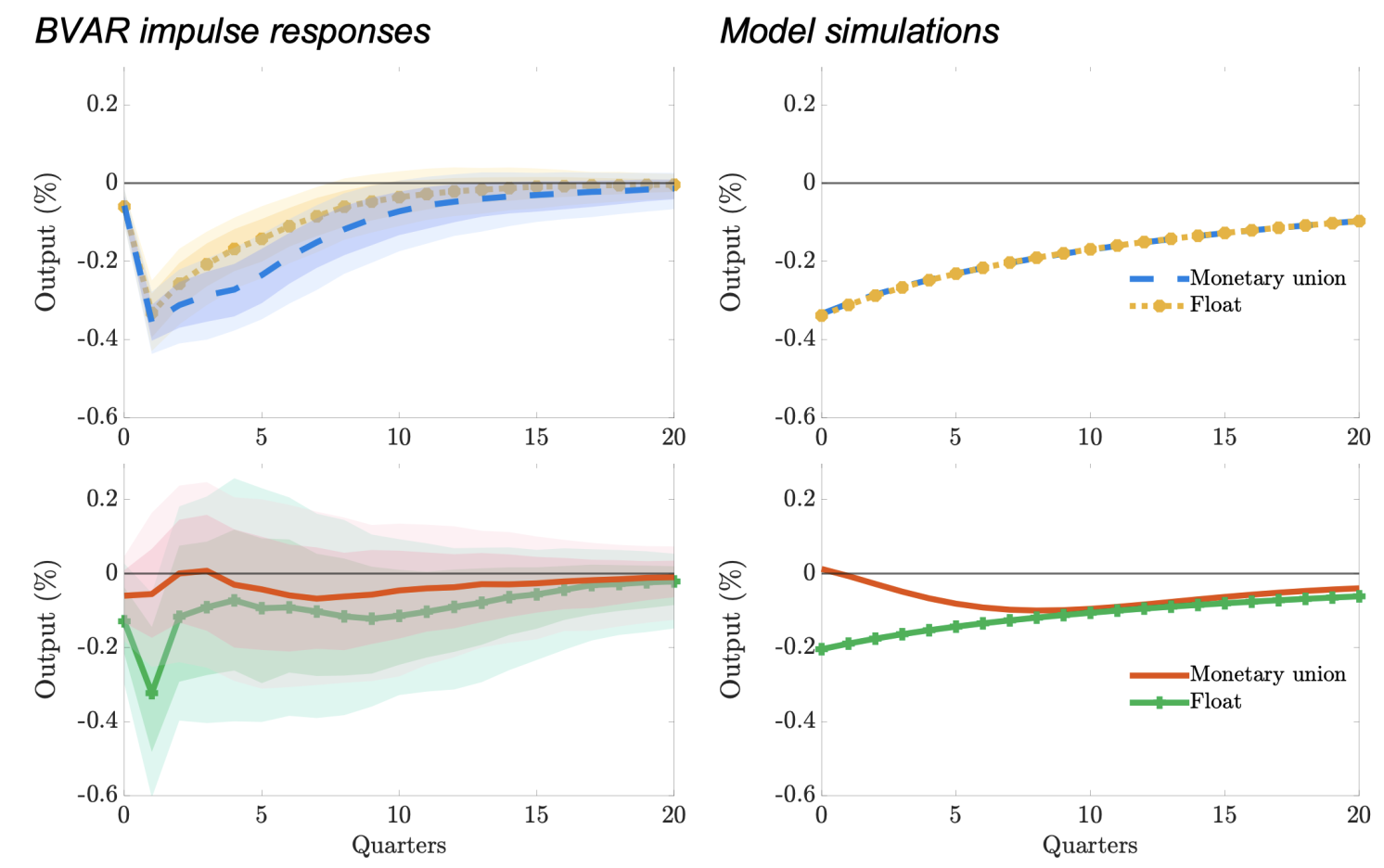

Figure 2 Output response to common (top) vs. country-specific (bottom) uncertainty shocks

Notes: Impulse responses of output to common (top) and country-specific (bottom) uncertainty shocks according to estimated BVAR (left) and structural model (right). Blue dashed and solid red lines indicate VAR responses in euro area countries (monetary union), yellow lines with markers/green lines indicate responses under flexible exchange rates (float). Shaded areas indicate 68% and 90% highest posterior density intervals. Horizontal axis: time after shock in quarters; vertical axis: real GDP response in percent.

The left panels of Figure 2 show the impulse responses: how an uncertainty shock impacts economic activity over time, measured by real GDP. In the top panel, we show the adjustment to a common uncertainty shock for countries with flexible exchange rates and for EA countries. There is no difference. In the bottom panel, we show the result for a country-specific uncertainty shock: it lowers economic activity in countries with flexible exchange rates but hardly affects economic activity in euro area countries. Considering the received wisdom, this is a surprising pattern. After all, monetary policy in the euro area cannot and does not accommodate country-specific shocks.

An Explanation: Price Level Expectations Are Anchored by Union Membership

We explain this result in a structural two-country model of a monetary union, extending the closed-economy setup of Basu and Bundick (2017). In the model, the ‘Home’ country is small and has negligible influence on union-wide aggregates, which in turn determine the common monetary policy. ‘Foreign’ represents the larger rest of the union. Uncertainty shocks in the model widen the distribution of supply and demand shocks. The model is estimated on euro area data to match the impulse responses to common uncertainty shocks. We find that the estimated model indeed predicts weaker effects of country-specific uncertainty shocks, both compared to common shocks and to a counterfactual with floating exchange rates. We show these results in the right panels of Figure 2 above. These findings are particularly noteworthy because the impulse responses to country-specific uncertainty shocks were not targeted during the estimation of the model.

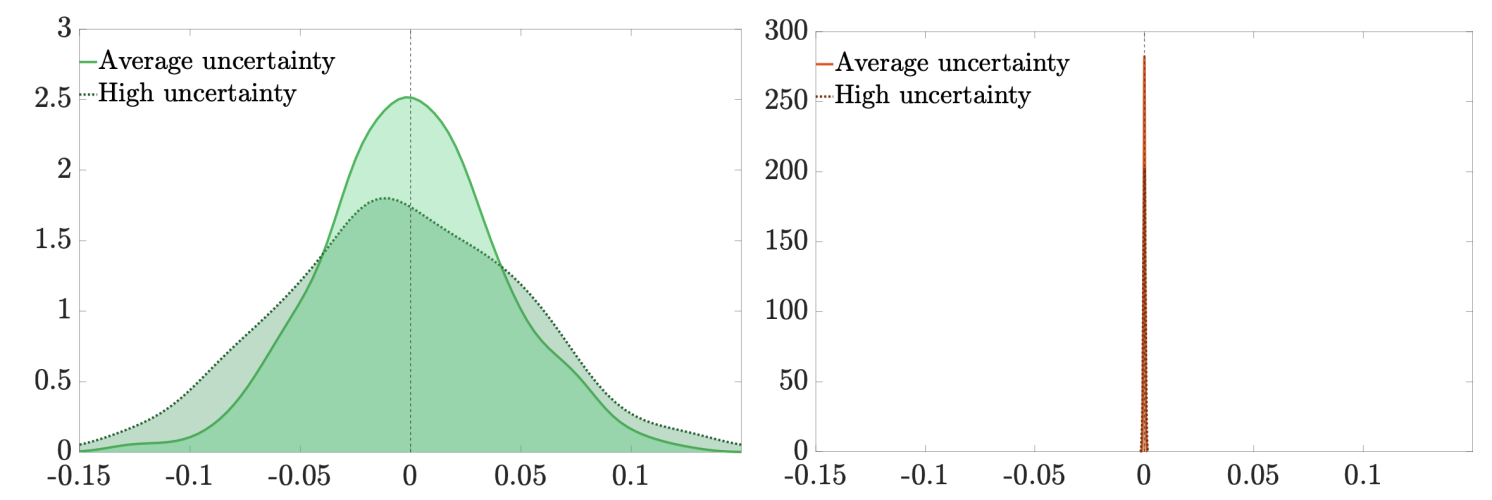

Based on counterfactuals, we establish that price level risk is key for this result. Absent a monetary union, when a country’s monetary policy targets inflation, an increase in uncertainty is associated with an increase in price level risk. We illustrate this in the left panel of Figure 3, which shows the simulated long-run distribution of the price level after a demand shock with and without heightened uncertainty. Price level risk, in turn, is detrimental to consumption and investment, as we show in the paper. In contrast, even when country-specific uncertainty goes up in a country operating within the monetary union, the long-run price level remains anchored by the union level. Long-run (relative) purchasing power parity, as in the data (Bergin et al. 2017), implies that a country’s price level must converge to the union level in the absence of a flexible exchange rate.

Figure 3 Union membership eliminates price level risk

Notes: Distribution of long-run price levels 100 quarters after random one-time level demand shock drawn from distribution with average uncertainty (solid line) and after one-standard deviation country-specific uncertainty shock (dotted line) under floating exchange rate (left panel) and in monetary union (right panel). Horizontal axis: price change in percent; vertical axis: density.

Policy Implications

Our research highlights a key benefit of monetary union membership: the reduction of price level risk arising from country-specific uncertainty shocks. The nominal anchor provided by the union not only eliminates the inflationary bias, as is often argued (Alesina and Barro 2002), but also shapes business cycle dynamics. This finding has policy implications: heterogeneous exposure to uncertainty may be less problematic than one might think. This reduces the need for targeted policy intervention at the country level — whether by the common central bank or by national fiscal policy. Instead, it may be sufficient to rely on the stabilising effects of a credible nominal anchor, even in troubled waters.

See original post for references

EU yes, Eurozone NO.

Interesting findings, but my first thought would be that the conclusions might only hold given the strong probability that the states in both groups adhered to mainstream-macro supported policies. If the non-monetary union states aren’t using all the tools at their disposal – and I’m willing to bet none of them have – then this wouldn’t be an advantage of unions in general.

An impressive academic optic of the eurozone – however, as with all things academic, the use of counterfactuals in arguments is notoriously difficult to validate without a deep understanding into the assumptions made in the underlying model.

The emerging challenge of the eurozone are the high intra country barriers of the single market and especially for services as identified by Mario Draghi in his Competitiveness report: The EU’s internal trade barriers are actually higher than the ones Donald Trump has just imposed on Europe and the rest of the world.

Add to that ongoing higher regulation in digital markets & services it becomes more apparent that more agile economies will likely do better than the Eurozone.

It’s one of the reasons why Brexit wasn’t the four horseman & the apocalypse event predicted by remainer’s & the anti Brexit brigade – in fact looking back, Brexit was more of a political event than an economic event – UK after 5 years of Brexit still a reasonable sized economy doing as well, possibly better than Germany, France and Italy.

Going forward – if the even newer 50% Trump tariffs come into play on the EU – all bets are off – Germany and Ireland would be disproportionately hit very badly -this will have a major impact on the Eurozone but in the wider European market too.

Lordie.

First you are straw manning what most Brexit skeptic said.

Second, the UK undeniably took a sustained hit to growth. See for instance: https://niesr.ac.uk/blog/five-years-economic-impact-brexit

Third, the loss of EU workers hurt the NHS significantly and more generally, led to a big increase in immigration, see:

Immigration and in particular its purported effects on housing, schools, and the NHS were big drivers of the voter shift to Reform in recent local elections.

There was an economic ‘hit ‘ no doubt – plus a little event called Covid was a cofactor – what nobody has been able to validate is the OBR prediction of a 4% hit to the economy – partially this was their weak counterfactual arguments, plus they didn’t take account of three post brexit factors ( obviously) which includes £/sterling appreciation since Brexit, reclassification of export/import definitions ( by the ONS , UK statistics agency) and the significant but continued growth in service led exports the EU.

UK is still 6th largest economy in the World – it’s growth is projected to be much stronger than most of the major economies of the EU – go figure. Future tariffs from US on EU will not help the eurozone.

Your point on immigration – absolutely – Reform will be a big winner – Labour will be a huge loser. Immigration post 2019 it now transpires was driven by student visas and their family dependents who did not come to work for the NHS – in total immigration for 2023/24 led to c. 35,000 additional migrant workers to the NHS whilst welcome it is ‘ peanuts’ in the scheme of things.

Meanwhile, no sign of illegal migration abating but a continuous and increasing bill of £15bn per annum for asylum seekers and illegal migrants.

First, your “hit” in quotes is a misleading minimization. The reduction in growth lasted for years and put the UK on a permanently lower trajectory.

Second, if Brexit was so great, why do most UK citizens now think it is a mistake?

https://news.sky.com/story/most-people-think-leaving-the-eu-was-a-mistake-but-dont-expect-politicians-to-reopen-the-brexit-question-13300046

And why is the UK unwinding it as much as it can? See:

And

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mfYrJXsDUXE

Much still depends on whether you believed in Brexit as a long term positive process or you are more a believer in the Remainer tropes peddled by the likes of ( in the UK) by the FT or The Economist.

Catherine McBride wrote a good piece recently on Substsack which demolished albeit in a fairly scientific way, the reason why Starmer’s reset isn’t worth the paper its written on.

https://open.substack.com/pub/catherinemcbride/p/everything-the-governor-of-the-bank?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=1wllqy

Forgive my cynicism of friendly opinion polls – the UK cannot rejoin the ‘old ‘ EU of 2016 – to rejoin the new EU would necessitate us committing to join the euro – this question when put to the voters elicits a very different response.

Starmer trying to get back into the EU via the back door – hey, worth a try – trouble is, it’s hard to fool all of the people all of the time – as the National Farmers Union and Fisheries trade association have articulated.

You are not new here, and you’ve already been put in moderation for violations of our site Policies. Yet you persist.

Your comment above (and the earlier ones) are sophistry. Your fallacious arguments include:

1. Straw manning. The reason for citing recent voter polls on Brexit was to show how voters feel now about the choice. They clearly on regret it and that propensity has only increased over time.

The reason for citing Starmer’s attempt to roll back elements of Brexit is that it confirms government concern about voter unhappiness. It is an attempt at appeasement.

Nowhere did I say that these moves would yield much in the way of benefits. Your discussion of McBride is a straw man, misrepresenting my argument.

2. The “can’t rejoin” is beside the point and an additional straw man. You keep trying to depict Brexit as a success. I demonstrated it wasn’t in economic terms and the UK public agree for that and other reasons. So now you attempt to shift grounds, a further demonstration of bad faith argument.

3. Your “Remainer tropes” is ad hominem. You need to debunk the arguments and not engage in smears.

I trust you will find your happiness on the Internet elsewhere.

A great unexpected benefit to loss of economic sovereignty, I guess, “L’effet tampon“.

I’m sure that this was a consideration during the conception of the common currency but there was also plenty of talk on the continent, at least, of an eventual fiscal union to complete the project. I’m sort of glad that never came to fruition, considering just how much power has been left by the Council to be absorbed by the Commission, and how weak the ECB has looked for the past five years or so.

Thanks for this. I used to be one the people who thought “a bunch of countries will crash out of the Euro”, partly because currency unions in the past in Europe never lasted. Then Yves educated us all about logistics and expectations and how this was pretty much impossible without such societal upheaval as to be truly awful and economy collapsing so I revised my views.

It is interesting to learn of reasons why there may in fact be factors to keep even unhappy countries part of the bloc. Plus even though the REASONS are bad (“let’s all gang up on Russia and support Ukraine dodgy people”), there may be some good that comes of this in terms of encouraging certain countries to finally agree to shings like debt-sharing etc once they see how precarious a position they themselves are in.

One key weakness in modern macroeconomics (and this includes some popular heterodox theories) is the failure to fully understand and model the differences in policy options between relatively large economies and small open ones. A key reason why governments in smaller EU countries were and are very keen on the Euro is that the stresses involved in maintaining the ‘impossible trinity‘ of monetary policy, which tend to be far harder for small countries with currencies that were not widely traded. European countries that stayed out of the Eurozone have often had to maintain very damaging interest rate levels (either too high or too low) in order to maintain what is seen as an economically and/or politically necessary currency level.

For all its faults (mostly due to its original design, in particularly the ordo-liberalism of the Bundesbank influence), the Euro provides a high degree of stability for those economies which are small, but generally within the median of economic performance. Plus of course it reduces profit taking through arbitrage opportunities (otherwise known as rip-off exchange rates).

I don’t think EU would approve that Tolstoy reference.

I don’t know about an anchor in troubled waters as it seems to be more an anchor tied around the necks of member states. Consider. The EU has evolved rapidly into an authoritarian body that is demanding that they have a strong say in the economies in the member states and punish members States by withholding EU money owed to them Just ask Hungary. They are also demanding that members not only kick in money and resources to the sinking ship of the Ukraine but also money into a gigantic fund for arms which Brussels will have control of. Did somebody say slush fund? And through mandated sanction packages against Russia, the EU is eviscerating itself economically but they will not quit and are already working on the 18th sanction package. If there are troubled waters, it is because it is mostly self created.

Well said. I am absolutely terrified that Carney is talking about this insanity for Canada.

These days i find that the main risk of EU membership is political. We are seeing how just a couple of countries (France and Germany) which are heavy weights within the Union, drag the rest of the countries, willingly or unwillingly, to political decisions which are not exactly in favor of any or all of the union members. Let’s say, for instance, Russia sanctions. Politics not exactly for the better.

Always good to remember what the EU is and has become.

1. It’s a badly implemented Political Union geared around (necessarily) Germany and France

2. It’s a high regulation high social cost behemoth

3. It’s a genuine non optimal currency area given a lack of fiscal and capital competences

4. The single internal market is pretty much only in goods – high internal barriers make services trade incredibly expensive – Draghi competitiveness report ruthlessly acknowledges

5. As a consequence of all of the above – the democratic deficit amongst member states increases as the European Council & European Commission vie for decision making powers

Interesting. My friends in Spain–a mid-sized (?) and these days relatively health economy–have always argued that the loss of control over monetary policy made it hard for socialist govts to enact welfare provisions, that a deeply neoliberal Brussels was an anchor on progressive legislation/economic planning. (See Greece.) I see–above–an argument that small countries and their currencies are today too vulnerable to manipulation to take advantages of such control, but would like more conversation about that. Given that more social protections seem to be going out the window on the way to militarization presently, this article runs counter to my received sense of the matter; I’m skeptical, but will need to read again.

Crazy to remember that the perceived upside half a century ago was that these countries would never go to war with one another again. Or that there was a long period when Felipe Gonzalez and Mitterand were both in office when one might have hoped for a transformative left surge. . .

Certainly, there is improved fiscal and currency stability for smaller countries in the EU, but there also is a reversion to the mean, in that if a EU country wants to try and do better, say, follow a more Chinese-style economic policy, or even US, by heavily subsidizing AI or optical chips, etc., is impossible.

My take is that it’s a two-edged sword that assumes (often correctly, but not always) governments (in Europe) can only be middling to lousy. That is why Norway declined to join the EU, and has done better than the average.

And another aspect, perhaps some European countries would oppose the genocide in Gaza if they were independent, but within the EU, they are forced to participate in the greatest evil of the 21st century–doing nothing to stop genocide is against the genocide conventions. I will not head to Godwin’s Law, but …

The other key reason’s why Norway has still remained outside of the EU are:

– it’s out of The Common Agricultural Policy

– it’s Very much out of the Common Fisheries Policy

– it’s out of the Customs Union.

All of the above are accretive dis-benefits to a country like Norway – the benefits of managing an economy the size of Norway outwith the above are significant and the Norwegians, to their credit have made a good job of being outside of much of the regulatory burden of the EU – EFTA being more agile & flexible.