his is likely to create more, not less, illegal immigration to the US.

By threatening to tax remittances — money sent from migrant workers in the US to their families back home — the Trump administration is bringing to life one of the worst nightmares of developing and emerging economies worldwide: the end of the long-rising tide of remittance inflows. These inflows have become an essential source of income for families, communities and nations in the so-called “Global South”.

On Wednesday, the Ways and Means Committee of the US House of Representatives approved the chairman Jason Smith’s proposal to impose a 5% excise tax on remittance transfers that would cover more than 40 million people, including green card holders and non-immigrant visa holders, such as people on H-1B, H-2A and H-2B visas. Until now, remittances were not subject to US taxation, making this a stark policy reversal.

The proposal reads as follows:

This provision imposes a five percent excise tax on remittance transfers which will be

paid for by the sender with respect to such transfers. The provision requires that the tax be

collected by the remittance transfer providers and the remittance transfer providers are

responsible for remitting such tax quarterly to the Secretary of the Treasury.The provision also makes it clear that remittance transfer providers have secondary liability for any tax that is not paid at the time that the transfer is made. The provision also creates an exception for remittance transfers that are sent by verified U.S. citizens or U.S. nationals by way of qualified remittance transfer providers.

With 26 votes in favour and 19 against, the committee approved the legislation proposed by Smith. The Democratic caucus spoke out against the proposal, while Republican legislators showed unanimous support. The proposed tax on remittances forms part of the administration’s Trumpian-titled “One, Big, Beautiful Bill” that is expected to be voted on by the full House of Representatives by May 26 and, if approved, sent to the Senate for discussion.

Trump recently said he is also working on a presidential memorandum to “shut down remittances” sent by people in the US illegally without revealing any specifics, such as how it would work.

Proponents of such measures argue that limiting, prohibiting or taxing remittances would make life more difficult for undocumented immigrants in the US while raising much needed revenue for the US government. However, it also risks exacerbating poverty and economic uncertainty in the US’ own “backyard”, particularly small Central American states for whom remittances have become the major source of national income.

And that, paradoxically, could end up fuelling even more illegal immigration to the US.

More Migration = More Remittances

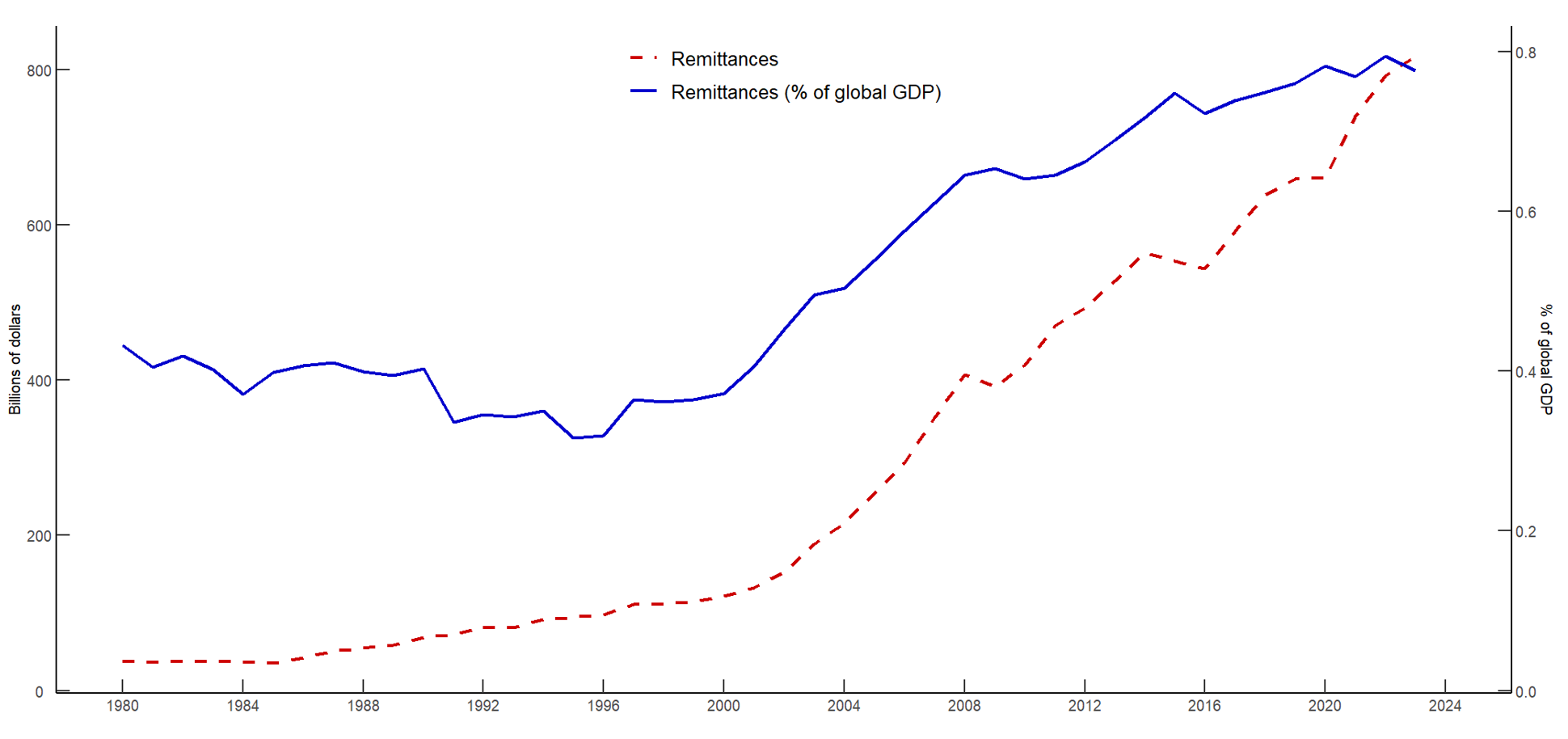

As the graph below (courtesy of the Fed) shows, remittances have grown at breakneck pace, increasing more than five fold since the start of this century to reach almost $800 billion in 2024.

The main reason for this surge is that more people are working overseas than ever before. The total number of migrant workers globally more than tripled between 2010 and 2020, from 53 million to 170 million, according to the International Labor Organisation (ILO). Migrant workers often end up doing jobs that are deemed essential, many of them low paid. Many ended up filling the ranks of the briefly celebrated but quickly forgotten “essential workers” in advanced economies like the US during the COVID-19 pandemic.

And it is the world’s poorest and most vulnerable economies that depend on remittances the most, and are therefore most at risk from the Trump administration’s proposed tax raid. To paraphrase the title of Michael C Klein and Michael Pettis’ 2020 book, trade wars are, ultimately, class wars.

Many of these economies, already pummelled by the double whammy of the COVID-19 pandemic and the surge in global inflation and interest rates that followed, are already teetering on the edge. As Jomo Kwame Sundaram has regularly warned in pieces cross-posted here, recent policies in the Collective West, particularly the US, have been increasing the financial strains in developing economies, with the real danger of setting off cascading crises.

Now they face another double whammy: declining remittance payments in the months to come, assuming the Trump administration continues to escalate its crackdown on migrant workers, together with a 5% tax on the remaining remittances. That tax, if approved by Congress, is likely to ramp up the financial pressure even higher, and essentially constitutes a 5% tax on many of the poorest communities in the poorest nations, including some in the US’ direct neighbourhood.

As the Fed notes, of the estimated $818 billion in remittance flows in 2023, of which an estimated $93 billion came from the US, more than any other country, $656 billion went to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs):

Remittances continue to be a key source of external financing for LMICs, surpassing foreign direct investment (FDI) and official development assistance. Unlike capital flows such as FDI, which are often concentrated in a few large emerging economies, remittances are more evenly distributed across developing nations…

Furthermore, remittances constitute a significantly larger share of GDP in many developing nations, highlighting their critical role in financing the current account and promoting macroeconomic stability. In 2023, remittances accounted for over 20% of GDP in countries like El Salvador, Honduras, Nepal, and Lebanon, compared to FDI which accounted for less than 4% of GDP in these nations.

If the GOP’s proposed tax on remittances, together with Trump’s proposed ban on remittances by illegal immigrants, have their desired effect, these money flows will begin to subside. What’s more, this will be happening precisely at a time when Trump’s tariffs are (in the words of Michael Hudson) threatening to “radically unbalance the balance of payments and exchange rates throughout the world, making a financial rupture inevitable.”

The Most Vulnerable Economies

One country that is likely to be hit hard is India, the world’s largest recipient of remittance inflows — with a total haul of $83 billion in 2024. As Akshat Shrivastava, founder and CEO of The Wisdom Hatch Fund, warns, US non-resident Indians, or NRIs, account for roughly 28% of all remittances sent to India:

This is close to 32Bn$ (annually). To put this in context, India’s education budget is 15Bn$. If we miss out on such a large volume of money, it will have far-lasting consequences. When an additional layer of tax is put (sic), they are likely to send less money. This impacts our foreign reserves.

NRIs have been helping India massively: it is easy to brush their contributions aside. But, if they have less incentive to invest due to such taxations, the implications will be far lasting.

That said, India gets the lion’s share of its remittances from other regions, including the Middle East and the UK. The same cannot be said of Mexico, the world’s second largest recipient of remittances. Of the $64 billion of remittances it received in 2024, 96.6% came from the US, according to BBVA Research.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum lambasted the proposed tax in a recent morning press conference, calling on Republican lawmakers to reconsider it, warning that it “would damage the economy of both nations and is also contrary to the spirit of economic freedom that the US government claims to defend.”

Sheinbaum also accused the US government of targeting migrant workers with double taxation:

How are they going to tax [remittances] if Mexicans in the US already pay taxes? All Mexicans living in the United States pay taxes, whether they are have documents or not, they all pay taxes. There are even states that already tax remittances.

In other words, they will face triple taxation. Carlos Marentes, executive director of the Border Farm Workers Center in El Paso, agrees, telling the Border Report:

I have seen farm workers send remittances and show their Mexican passport with the H-2 visa. This is money they earned working, that their employer deducted taxes from. In addition, when they send the money home, they pay the (electronic wire) fees.

Those fees are often exorbitant, especially for smaller transfers (typically around $200). The World Bank’s Remittance Prices Worldwide database reveals that the global average cost for sending $200 in the first quarter of 2023 was about $12.50, or 6.25%.

Remittances have become one of Mexico’s mainstays in recent years, particularly in the rural communities hit hardest by the devastating effects of NAFTA on Mexico’s small-scale farmers. In 2024 alone, Mexico received $64.7 billion in remittances. That’s more than any country on the planet bar India, and is the equivalent of 3.4% of GDP. In some Mexican states, such as Puebla, remittances can represent as much as 10% of total revenues.

As we reported last week, the cumulative value of remittance income in the first three months of 2025 was $14.26 billion dollars, which is slightly higher than the $14,083 billion reported last year. This is despite the Trump administration’s crackdown on migrant workers, resulting in US-based Mexican workers losing over 130,000 jobs in the first quarter of 2025, according to data from the Latin American and Caribbean Remittances Forum.

In other words, this vital lifeline for so many Mexican families has so far weathered Trump’s immigration crackdown surprisingly well — presumably because the migrant workers who have held onto their jobs are sending more money than usual back home. But as we warned in that post, whether this trend continues or begins to reverse depends on the vagaries and whims of the Trump administration.

If the US House and Senate approve the Trump administration’s proposed 5% tax on remittances, which presumably they will given the GOP has majorities in both houses, it is likely to heap further pressure on Mexico’s already slowing economy. As Adam Tooze pointed out recently in his Chartbook newsletter, the outlook for the Mexican economy has deteriorated sharply in recent months while investment optimism is also plunging.

While there are a number of internal reasons for this economic slowdown, in particular the Mexican government’s sweeping reform agenda, which will limit the ability of corporations, particularly in the mining sector, to extract wealth at exorbitant social and environmental cost, the biggest risk to Mexico’s economic health comes from the Trump administration’s constant threats of tariffs, mass deportations and military intervention.

As the US ratings agency Moody’s warned recently, US tariffs could harm Mexico’s manufacturing, automotive, and technology industries. These disruptions may lead to currency depreciation, increased inflation, and constraints on interest rate cuts, which would in turn dampen loan demand. The resulting volatility in exports, exchange rates, and inflation could also reduce banks’ risk appetite.

A sharp fall in remittance revenues will only exacerbate these pressures. The impact on smaller countries in the US’ “backyard” is likely to be even greater, however. As the map below shows, remittances, primarily from the US, are the primary source of revenues for many Central American and Caribbean states, including Nicaragua, where they provided a staggering 26.2% of GDP in 2023, Honduras (26.1%), El Salvador (24.1%), Guatemala (19.1%), Haiti (18.7%) and Jamaica (17.9%).

🌎 Los envios de remesas son una parte fundamental de las económicas iberoamericanas, hasta representar en buena parte de centroamerica el 25% del PIB.

🔗https://t.co/jy3EGZHaRL pic.twitter.com/mfYJ2PEMfe

— FairPolitik (@FairPolitik) May 12, 2025

Remittance payments have become a vital source of development income for rural communities in Mexico and other parts of Central America. As NBC reports, “in small migratory towns like Cajolá, Guatemala, it is not unusual for the entire economy to be built off remittances, the funds sent by migrant workers back to their home countries.”

Marentes gives the example of programs such as “3×1” and “2×1,” which invited Mexican workers in the US to send a separate remittance for public works in their communities, which the local government matched with its own funds. From the Border Report:

State or federal governments pitched in, hence the double and triple match in “2×1” and “3×1,” with the numeral 1 representing each peso (19 pesos equal a dollar) the migrant sent from abroad.

Funds were used to build schools, parks, roads, community centers and sports fields, according to the website for Programa 3×1 para Migrantes, whose last entry appears to be from 2017.

The Downsides and Dark Sides of Remittances

However, as remittance payments have soared globally, governments, communities and families in the Global South have come to depend on a source of income that is far from guaranteed. During the lockdowns of 2020 and 2021, the World Bank predicted double-digit falls in remittance flows but the forecasts were wildly off target. In the end, global remittances declined by only 1.7% in 2020 and in some regions, such as Latin America, they actually ended the year in positive territory. That trend then accelerated sharply in 2021.

But now the US, the world’s largest source of remittance payments, is determined to reduce the money flow.

That all being said, remittance payments have their downsides and dark sides. The mass influx of immigrants, while potentially being “a net good for the US, increasing the total wealth of the population… hurts the prospects [of many Americans]” while, of course, plying corporations with cheaper labour, as the immigration economist George J Borjas noted in a 2016 article for Politico magazine. There are other downsides, which we laid out in our 2021 post, “Remittances to Latin America Surge, Even As Virus Crisis Continues to Bite in Host Economies“:

For example, there is the brain drain effect as many of the most skilled workers in low and middle-income countries move to host countries that offer better employment incentives and opportunities. If this process goes too far, it can exacerbate, rather than mitigate, inequalities between countries by depriving low-income countries of their best and brightest. Some countries end up facing acute labor shortages. The Philippines, for example, where roughly two in five qualified nurses end up working abroad, now has the lowest number of nurses per capita in Southeast Asia.

This can end up perpetuating a vicious cycle. The more that low-income countries function to provide cheap labour to high-income economies, the more difficult it is to develop a strong economy at home. As a result, yet more people leave for greener shores. Of course, there are myriad other pressures, pushing people in the Global South to migrate northwards, including climate change, resource wars and drug wars, political instability and all-round economic hardship exacerbated by the virus crisis.

It is too early to tell how Trump 2.0’s two-pronged attack on remittance payments, through (a) taxing them and (b) banning them altogether for undocumented migrant workers will eventually play out, assuming they end up taking effect. But it’s safe to assume that they’ll be lots of messy consequences, most of them unintended.

One clear beneficiary will be the informal economy, which is ironic given that the COVID-19 lockdowns and travel bans helped to formalise international payment transfers like nothing before them. Many migrant workers, will end up paying their families with cash, or perhaps even cryptocurrencies or stablecoins, whose use the Trump administration is doing everything it can to promote.

We have already seen this happen in Cuba after the Trump administration forced Western Union to indefinitely suspend its remittance services to Cuba in mid-February as part of a package of sanctions that includes an attempted embargo on Cuba’s international medical missions. As AFP reports, people quickly adapted to the new reality by making cash transfers “using ‘mules’, who move money from abroad in exchange for a fee.”

That fee, according to AFP, is roughly equivalent to Western Union’s, at around 10%.

Another likely unintended consequence is more US=bound migration, as economic conditions deteriorate in Central American countries that depend heavily on remittances. According to remittance experts interviewed by La Jornada, “prohibiting, limiting or adding a tax to remittances could harm the communities that depend on them, create new bureaucratic hurdles… for US businesses and, paradoxically, end up causing even more illegal migration to the United States.”

One other likely outcome is greater international unity… against the US. A case in point: in Mexico, for the first time in a very long time, all opposition parties, including those slavishly aligned with US interests, have joined the Morena-controlled government in rejecting Washington’s proposed tax on remittance payments.

With Marco Rubio’s State Department sanctioning Cuban medical missions at a time when the US embargo on Cuba has zero international support, apart from in Tel Aviv, and Trump himself talking about drone bombing Mexico, invading Panama and turning Canada into the 51st state, there really is no telling how much of an unifying force Trump 2.0 could be in today’s world.

It has the “feel” of an intentionally cruel policy.

Proposed revision to the policy: proceeds of this tax to be used to fund Job Guarantee programs in less developed regions of the countries to which the remittances are sent.

—

I have come to doubt that “the arc of history bends the direction of justice”, but perhaps it may slightly wiggle in the direction of double-entry book-keeping.

Those who are prideful think they own everyone and that everyone owes them. Pride is the greatest sin for a very good reason.

But taxing estates is a double tax.

Have they got anything coherent on SALT yet? Or are they rewriting overnight again….

We should all make an effort to link the “Golden Dome” to the alleged pee tape.

If we’re cutting Medicaid by 800B to fund mulitary-industrisl-SpaceX folly such as a “Golden Dome,” might as well have a little fun.

Lordie. Everything is a double tax. The property tax you pay is a double tax (on your income). The tax you pay when you stay in a hotel is a double tax. Sales tax is a double tax. Trump tariffs are a double tax.

I don’t buy that estate tax is a double tax. It is a tax on their heirs, not on the dead person. This was NEVER NEVER NEVER income they earned.

Except for the “Guilded Class” who perpetually defer their “Unrealized Gains” by borrowing against them (at extremely low rates); thus cementing their ZERO income status.

An added bonus is that this same Class are the Architects of the Asset Bubbles (and very Assets) that they are borrowing against!!

Cruelty or could it be a way to boost Crypto? With concurrent cuts to the inspectors in charge of regulating Crypto, it might finally create a real demand for these (in legal contexts mostly) useless tokens.

Probably both cruelty and a way to boost Crypto. Contrary to what most crypto-boosters claim, cryptocurrency by itself does not guarantee your anonymity when conducting transactions. The existence of public ledgers, combined with signals intelligence cooperation from ISPs and cell phone providers, means government agencies can easily bootstrap enough data to identify a non-trivial amount of individuals trying to or actively sending money to others across borders via crypto, without needing to first get a warrant. They have been doing this since 2016.

From there, the IRS or other law enforcement agencies can then try to obtain a warrant to seize the individual’s private keys for direct access to the tokens on the ledger, for a bank or crypto exchange to turn over any private keys held in escrow or money that was given, or use civil asset forfeiture to confiscate those particular tokens or any electronic devices from anyone who might be a recipient or acting as a digital version of a mule. Either way, crypto as a means to bypass remittance taxes is at best a false promise, and at worse, a way to continue identifying non-native workers as fodder for ICE.

Once tokens are in the hands of those agencies, they’ll probably auction them off, tipping insiders or agency/administration favorites not unlike what happens at some Sheriff’s auctions/sales throughout the country. Because tokens are fungible in value, but non-fungible in terms of having a completely digitized base of their serial numbers, auctioned tokens could be obtained for a higher than market price, as a wink/silent-hint for corruption opportunities with employers who depend on immigrant labor, particularly unauthorized immigrant labor. Auctioned tokens become used to pay said labor in something they’ll already want for remittances, and those tokens are “allowed” to be remitted, until they are transferred from an immigrant’s account to a foreign recipient’s account. Because those tokens could be bought at or above market prices, and auctions timed to when tokens have a higher price, agencies gain more from auctioning crypto, than just seizing cash of equivalent value.

This came to mind as well. How does this work for sending payments of something like USDC when crypto wallets are borderless?

Truly disgusting “Policy”.

Effectively a Boot-on-the-Neck of some of the poorest people on the planet.

Meanwhile, not a single penny of the “Ukrainian Aid” or “Israeli Aid” has been subject to Audit, nor have there been any Elections.

Ditch the Tax, and file it under reparations for both the United Fruit epoch and Oliver North era of crimes-against-humanity.

There’s nothing paradoxical about policies that haven’t been thought through properly backfiring – they’re just plain dumb, like the wasting billions on the ridiculuous and risky Houthi campaign when everybody should have known from past experience it would fail. The dumb never learn, they just double down and adjust the narrative they spew out on all forms of public media. I was hoping that Trump and Co would prove me wrong by showing us that there ia method to their madness. Unfortunately, it is becoming clear there is no method, just madness. They’re so full of themselves they don’t ask others with knowledge and experience for their opinion. It seems the only way they learn, if at all, is the hard way.

Remittance economies keep countries under-developed. The incoming remittances boost consumption and imports while not equally boosting production in that country. Prices, especially of land, end up higher and make it harder for the receiving country to develop its own industries. Moreover, workers in that country, earning wages in that country, lack even that little purchasing power they would have normally enjoyed. Their best option? Work abroad, and remit–it’s a perpetual cycle.

An article such as the one above is written to defend the immigration-industrial complex, from which the globalist bourgeoisie has reaped incalculably more benefit than any of the migrant workers whose interest they are claiming to defend.

Talk about grift? The worldwide remittances regime is a big racket.

It’s one more thing that shows the difference between globalism, which is wrong, and internationalism, which is right.

If the policy sticks, Trump will have actually done the developing world a favour.

Your argument sounds something akin to the resources curse. I would have thought that the money brought into the country by remittances can stimulate internal demand which helps kick start growth. I know for a fact that the money received from Spanish workers in the booming economies of France and Germany in the post world war period were helpful during the the time of the so-called “Spanish Miracle” when the Spanish economy boomed, not principally, as customarily thought, on the back of tourism and workers receipts (though they were both significant), but also on a huge wave of industrial expansion, but note, an expansion that was behind tariffs and other forms of managing international trade. In the end, many of those workers returned to Spain. Maybe, like most things, its effects on a given country depends on a whole lot of factors.

Did you even read the article, Roland? Including the section titled “The Downsides and Dark Sides of Remittances” where I discuss not only how remittances end up harming workers (and benefiting corporations) in the country sending the remittances but also perpetuating a “vicious cycle” in the recipient economy:

You make a good point about incoming remittances boosting consumption and imports while not equally boosting production in the recipient economy, which is largely true. However, as St Jacques mentions, citing the “Spanish Miracle” of the ’60s and ’70s as an example, remittances can boost internal demand, which, in turn, can help fuel local development. Some migrant workers do end up going home where they launch their own businesses. I have met plenty of them in Puebla and Morelos.

But you then claim that “if the policy sticks, Trump will have actually done the developing world a favour.”

How, pray tell, is that?

By decimating one of their main, if not the main source of income and foreign currency — at a time when the global economy appears to be slowing down sharply, in large part due to the uncertainty caused by Trump’s tariff tantrums, and when most Global South economies are already struggling to service their external debt commitments?

What will happen if they can no longer service those debt obligations, as has already happened to a growing list of countries since the COVID-19 pandemic (Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Ghana, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Argentina just a month ago…)? That’s right: they get “bailed out” by the largely Washington-controlled IMF, with all the usual conditions attached.

When has that ever been good for a developing country’s development?

Thank you for saying this!

Totally agree and also want to note that in the EU context in case of Moldova, Romania, and (not yet in EU but has a huge diaspora population) Armenia. The diaspora population ends up taking up the liberal imperialist politics of their host countries and vote against their countrymen. Remittance economies exacerbate underlying social and political problems in a society and make them intractable.

The Philippines is possibly the best case study of how a multi-generational remittance economy just creates absolute dysfunction.

i wonder if this will have any effect on hawala or cartel based money flows. if they decide to start up / expand some sort of money bootlegging thing, because im guessing that if people can’t move money legally, they will try to do so illegally, which will open up new avenues for exploitation.