The world’s largest bilateral trade relationship continues to grow, but it’s a trend that is unlikely to last.

Donald Trump’s tariffs have not slowed down Mexican exports to the United States, as many predicted. On the contrary, in the first quarter of 2025, Mexico sold goods worth $131 billion, an unprecedented figure since records began, according to information from the US Department of Commerce’s Census Bureau. It represents a whopping 9.6% increase on the $119.8 billion reported in the same period of 2024.

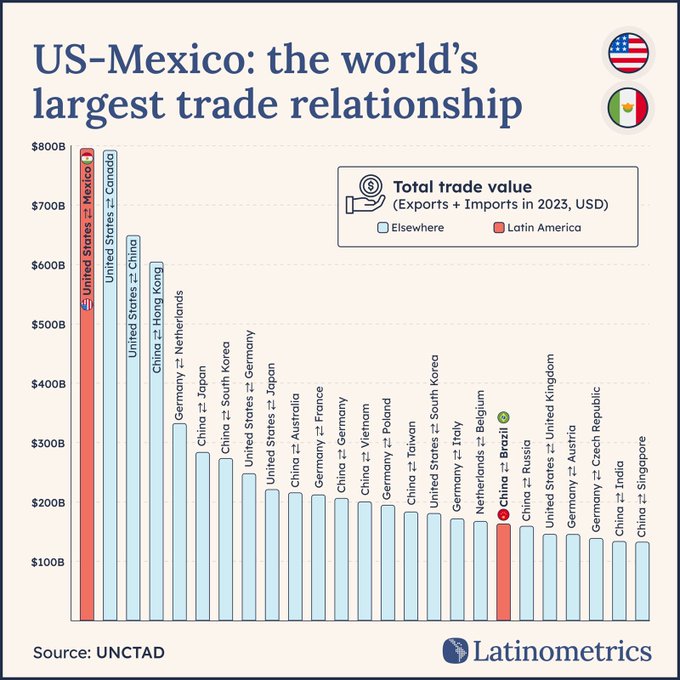

It was a similar though somewhat less emphatic story for Mexico’s imports from the US, which surged by 4.8% year on year to $84 billion. The result is that total trade between the two countries reached $215 billion in the first quarter of this year, another historic record. After notching up a total value of $840 billion last year, the world’s largest bilateral trade relationship seems, at first blush, to be going from strength to strength.

This has all happened despite the fact that since February 4 the Trump administration has imposed a 25% tariff on all Mexican export goods that are not covered by the USMCA trade deal, which is just over half of the total. Also, since March 12 the Trump administration has imposed a 25% tariff on Mexican exports of steel, aluminium and some derivatives of both metals, including canned beer.

Yet despite Trump’s tariffs, or in large part because of them, Mexico, like Canada and China, the US’ second and third largest trade partners, significantly increased its earnings from exports sent to the US in the first quarter of 2025. But this is a trend that is unlikely to last, especially if the US enters recession in the coming months.

In fact, trade between the US and fellow USMCA member Canada already fell sharply in March after the outgoing Trudeau government imposed retaliatory tariffs on the US — something Mexico’s Sheinbaum government has so far ruled out doing — which prompted further retaliatory tariffs from Trump. While Canada’s trade with the US slumped in March, its trade with other countries surged, reports Bloomberg:

The Trump administration’s duties on Canadian steel, aluminum, autos and other products, as well as Canada’s retaliatory levies on a range of American goods, led to a large pullback in activity between Canada and its largest trading partner in March. Exports to the US plunged 6.6%, the biggest drop in nearly five years, while imports fell 2.9%, Statistics Canada data showed Tuesday.

Exports to other countries jumped 24.8%, however, almost entirely offsetting the decline in outbound shipments to the US. Imports from other countries were also up 1%. As a result, Canada’s merchandise trade deficit with the world narrowed to C$506 million, down from C$1.4 billion in February and beating the C$1.6 billion shortfall expected in a Bloomberg survey of economists.

The country’s trade surplus with the US narrowed to C$8.4 billion, from C$10.8 billion in February.

While Canadian companies are looking to expand their domestic market and overseas markets beyond the US, the reality is that Canadian companies that are heavily dependent on the US market will struggle to make up for trade lost with the US elsewhere if Trump continues to hike tariffs on Canadian goods. This is particularly true if the global economy enters a downturn, as is looking increasingly likely. From Reuters:

While some Canadian companies have lost trust, those reliant on the U.S. market cannot entirely replace it, especially smaller firms, companies and industry associations have said.

Canada’s economy is less than a tenth the size of its neighbor and shipping overseas is costly.

Meanwhile, the US’ trade deficit with Mexico continues to grow, reaching $140.5 billion in the first quarter of 2025, according to the Census Bureau. This is all happening not just despite but in large part because of Trump’s tariffs.

Since Trump began tariffing the world, both consumers and businesses have been front-loading imports from countries subject to relatively lower tariffs, including Mexico, out of fear that the tariffs will spike again once Trump’s 90-day pause ends on July 9. Though Trump has implemented various tariffs targeting Mexico as part of his broader trade policy, he excluded the country from his list of nations facing steep “reciprocal tariffs.”

Amid the recent panic buying, US imports jumped 41.3% for the quarter — the largest rise since the third quarter of 2020, when many global economies, including the US, began to emerge from the first lockdowns. This explosion in pre-tariff imports has been identified as one of the main factors behind the US economy’s sharp slowdown in the first quarter.

Unfortunately for Mexico, the relief is likely to be short lived. As US businesses and consumers grapple with rising prices and supply shortages, consumption will inevitably fall.

It has also taken time for Trump’s tariffs to feed through to customers, but that is now beginning to happen. Just this week, Ford announced price rises of up to $2,000 on three models produced in Mexico, the Maverick, Bronco Sport and Mach-E, citing higher US tariffs on imported vehicles as one reason for the adjustment. US retailers expect a drop of 20-30% in imports in the coming months, according to Goldman Sachs analysts.

As Yves warns in her post Complacency, Denialism and the Risk of an Economic Trumpocalypse, given the scale of disruption and dislocations caused thus far, not just by Trump’s tariffs but also DOGE and the immigration crackdown, “it’s hard to have a good picture of where things stand in in the US and where the bottom might be”:

That is not merely the result of information being retrospective in what looks to be a rapidly accelerating downswing, but also small businesses and/or intermediate goods producers taking the biggest hits, and they are generally not well studied.

But based on the tone of the press, discussions with people in the US, and a very recent and short trip to New York City,1 much, and arguably too much, of the US seems to be in summer of 1914 mode: cheerfully living in a sense of normalcy that is about to vanish permanently. To put it another way, if there was a sufficiently widespread appreciation of what was looming over the horizon, May 1 would have seen the launch of open-ended general strikes.

Trump really is well on his way to implementing a reactionary restructuring of the US and international economy. “The end of globalization” is too bloodless a formula to convey the severity of the dislocations that have only started to arrive.

Even in the vanishingly unlikely scenario that Trump were to abandon his tariff policies in the next week, the confusion and interruption of supplies will still have done considerable harm. The longer they remain in place, the more that damage, particularly small business closures and downsizings at small and bigger enterprises, will become permanent.

The High Costs of Dependence

And that is bad news for the US’ largest trade partner, Mexico. As we’ve mentioned before, there are few more extreme examples of economic dependence than Mexico’s relationship with the US. Mexico ships more than 80% of its exports to its northern neighbour, many of which are produced by US companies based in Mexico. Those exports account for just over one-quarter of Mexico’s GDP, which is why many analysts singled out Mexico as the G20 economy most vulnerable to Trump’s tariffs.

This is not the only way that Mexico has grown dangerously dependent on its northern neighbour. As we have previously reported, Mexico, the birthplace of modern maize, is heavily — and increasingly — dependent on US imports of GM corn despite former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s ultimately failed attempts to ban its use for human consumption.

More dangerous still is Mexico’s overweening dependence on US energy to fuel its national grid. Despite AMLO and Sheinbaum’s long-term goal of achieving energy independence, Mexico imports more than 70% of the natural gas it consumes through a network of pipelines stretching from Texas deep into Mexico’s interior. With natural gas now producing over 60% of Mexico’s electricity, Mexico’s dependence on US energy has become Mexico’s “unspoken” Achilles’ heel, as the New York Times recently reported:

There are no signs yet that Mr. Trump has sought to use the gas exports as an additional form of leverage. But while Mexican authorities generally refrain from drawing attention to the issue, some officials have framed the fuel imports as a glaring vulnerability.

Juan Roberto Lozano, a director at Mexico’s National Energy Control Center, acknowledged this dependence in an interview with the trade publication Natural Gas Intelligence in February, calling it the “elephant in the room” of Mexico’s energy policy.

“The Trump administration is totally aware of this overreliance,” he said, adding, “It’s completely plausible that energy may become a point of contention between Mexico and the U.S.”

…

“This is an issue of national security,” said Raul Puente, head of the underground hydrocarbon storage unit at Cydsa, a Mexican company that has been urging authorities to boost emergency storage of natural gas in salt caverns in case supplies are cut off.

As tensions simmer over the Trump administration’s consideration of unilateral military strikes on cartels inside Mexico, Alfredo Campos Villeda, the editor of the Mexico City newspaper Milenio, weighed what could happen if Mexico stood up in defense of its sovereignty.

“How long could Mexico endure if the United States shut off the supply of natural gas, gasoline, and electricity?” Mr. Campos Villeda asked. “Twenty-four hours?”

Mexico’s outsized dependence on the US was all made possible by generations of comprador elites in Mexico, many of them educated in the US, some of them, including at least four presidents, on the payroll of the CIA, prioritising US interests over Mexico’s, which ultimately culminated in the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement, an a 2017 article in Le Monde Diplomatique’s Spanish edition neatly recounts (machine translated):

After the signing of NAFTA and the law on foreign investment that opened almost the entire Mexican economy (apart from the oil sector) to investors from the North, U.S. transnational corporations quickly established their domination in the neighbouring country. A phenomenon that the local elite welcomed with jubilation. President Ernesto Zedillo (1994-2000), while organizing the submission of his country’s productive fabric to the needs of the United States, forged the term “globophobia” to denigrate those who doubted the ability of free trade to guarantee the prosperity of Mexicans and to promote growth. Like most of the “neoscientists,” his colleagues and friends at the time, Zedillo had a doctorate in economics obtained in the United States.

His presidency, and before it that of Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1988-1994), were decisive for the reorganisation of the economy around one priority: exports. It was the second time that the country had been involved in such a project. But while the first time, under the presidency of Porfirio Díaz (1876-1880 and 1884-1911), it was based on minerals and agricultural products, the second experience has transformed Mexico into an exporter of manufactured products. With the help of the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Inter-American Development Bank, as well as with the unconditional support of the employers’ organizations and the national oligarchy, Salinas de Gortari and his acolytes remodeled the country.

Part of that remodelling involved Mexican smallholders being wiped out by the heavily subsidised US-grown beans, rice, and corn flooding the market. The entire network of small and medium-sized enterprises that came out of the industrialisation policy of the 1930s, deprived of financing, “proved incapable of coping with the foreign competition unleashed by Mexico’s entry into the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1986, NAFTA and, later, the World Trade Organization (WTO) – which succeeded GATT – in 1995.”

The average wage recorded between 1988 and 2005 did not rise above 60-70% of its 1981 level. The result, inevitably, was a mass exodus of rural workers to the United States, some of whom are now on the sharp end of Trump’s anti-migrant policies. Others ended up working — and in many cases, dying — for the drug cartels.

In the first quarter of 2025, US-based Mexican workers lost 132,190 jobs, according to data from the Latin American and Caribbean Remittances Forum. This comes on the heels of an earlier decline in the fourth quarter of 2024.

Remittances — the money sent from migrant workers to their families back home — is a key source of income, particularly in those rural communities that bore the impact of NAFTA. Last year, Mexico received $63 billion in remittances, almost all from the US. That’s more than any country on the planet bar India, and is the equivalent of 3.7% of Mexico’s GDP.

The bad news for Mexico, as for many other countries in Latin America, is that remittances have begun falling in recent months, as Trump’s crackdown on migrant workers has intensified. The good (and rather unexpected) news is that the inflows began picking up again in March, increasing by 2.7% year over year to $5.15 billion, according to the Bank of Mexico.

As a result, the cumulative value of remittance income in the first three months of 2025 was $14.26 billion dollars, which is slightly higher than the $14,083 billion reported last year. In other words, this vital lifeline for so many Mexican families has so far weathered Trump’s immigration crackdown surprisingly well — presumably because the migrant workers who have held onto their jobs are sending more money than usual back home. But again, whether this trend continues depends on the vagaries and whims of the Trump administration.

The growing weakness of the US economy could end up proving to be a double edged sword for Mexico. On the one hand, it could drag Mexico into a recession. However, as the Mexican economist Mario Campa points out, it is also likely that once US consumers suffer shortages and/or exorbitant prices and companies exhaust their Chinese inventories, the search for alternative suppliers will begin in earnest.

As such, Mexico could emerge as the relative winner of the trade war when the lingering storm clouds dissipate, just as happened the last time Trump was in power. This is probably one of the reasons why Mexico’s government remains committed to the trade agreement even as Trump threatens to escalate hostilities with his USMCA partners. On Wednesday, President Sheinbaum said:

We will defend the USMCA because it has been beneficial for the three countries. If President Trump takes a different approach, we will be prepared for any circumstance, but clearly we want the USMCA to remain.

But that will come at a cost. Trump administration officials are planning to use Trump’s tariff threats as leverage in USMCA renegotiations. One of the outcomes of those negotiations is likely to be increased Mexican dependence on the US. As Mexico’s former chief negotiator for USMCA warns, the US government seeks to change conditions in the manufacturing, technology and automotive sectors to tighten rules of origin and prevent Chinese products and investments from accessing the US market through Mexico.

This is likely to be easier said than done, however, given how much the US has grown to depend on Chinese-made products as well as how ill-prepared it is to reindustrialise, as Yves has repeatedly outlined. While some Mexico-based companies are already adjusting their supply chains in order to meet the current rules of origin and the Mexican government is striving to replace Chinese imports, for both the domestic and regional economy, trying to eliminate Chinese goods altogether from North American supply chains will be an all but impossible task.

I think there’s a typo at $14.26 million towards the end – the comparator is $14,083 million.

Fixed! Thanks Brian.

I believe that by now the last of the container ships carrying Chinese goods have docked on the US west coast, unloaded and have sailed back to China. And that means that shortages are baked into the pie with empty shelves looming. And for Trump, he will have to deal with the consequences of this and him claiming that it is all a result of the ‘Biden overhang’ is not going to fly. Everybody knows that it will all be a result of his tariffs. So maybe there may be a window of opportunity for Mexico opening up here. Mexico’s President Sheinbaum could ring up Trump to say that they have quit a few stocks of consumer goods in Mexico that could be shipped across the border to alleviate the worse of the shortages in return for, say, tariffs being pegged at only 10% so that he can claim a win and show his base that not only is he looking out for them (untrue) but that he was magnanimous to Mexico as they are our neighbour. And nobody would mention the actual source of those consumer goods.

I suspect that Salinas, Zedillo, Fox, Calderon and Peña Nieto were also on the CIA payroll.

The reason we know about the Litempo agents is that CIA station chief Win Scott was singularly indiscreet. He drew attention to himself, going so far as to invite all the Litempo presidents to his showy wedding in Mexico City. Scott was replaced in the early 1970s and died soon after in mysterious circumstances.

His replacement as station chief was a Latino who kept his head down. Business as usual continued, but the leaks stopped.

Mexico have so much potential but cartels is just too powerful and the place too corrupt that you have to wonder have this trade increase with USA even helped Mexico