Yves here. Although the Trump approach to tariffs is still a moving target, this post illustrates a core principle he repeatedly violates, called obliquity. We’ve written about it since 2007, based on the work of economist John Kay. The core idea is in a complex system, trying to cut a straight or simple path through it is destined to fail, and likely to backfire. That is because the system, as in the terrain, is too labyrinthine and responsive to interaction to be mapped.

So given Trump’s strong preference for aggressive frontal attacks, failure is almost guaranteed.

From a 2007 post, which quoted Kay in the Financial Times:

From the Financial Times:

If you want to go in one direction, the best route may involve going in the other. Paradoxical as it sounds, goals are more likely to be achieved when pursued indirectly. So the most profitable companies are not the most profit-oriented, and the happiest people are not those who make happiness their main aim. The name of this idea? Obliquity….

Obliquity is characteristic of systems that are complex, imperfectly understood, and change their nature as we engage with them. Forests have all these features. Fire is the greatest enemy of the forest….

Experience has shown that too much effort devoted to fire extinction is counterproductive. Time demonstrates, but only slowly, whether policy has gone too far in one direction, or the other. Forest management illustrates obliquity: the preservation of the forest is not best pursued directly, but managed through a holistic approach that considers and balances multiple objectives.

Forests are not the only systems structured in this way. Obliquity is equally relevant to our businesses and our bodies, to the management of our lives and our national economies. We do not maximise shareholder value or the length of our lives, our happiness or the gross national product, for the simple but fundamental reason that we do not know how to and never will. No one will ever be buried with the epitaph “He maximised shareholder value”. Not just because it is a less than inspiring objective, but because even with hindsight there is no way of recognising whether the objective has been achieved….

ICI is not the only company for whom greater emphasis on corporate financial goals led to less success in achieving them. I once said that Boeing’s grip on the world civil aviation market made it the most powerful market leader in world business. Bill Allen was chief executive from 1945 to 1968, as the company created its dominant position. He said that his spirit and that of his colleagues was to eat, breathe, and sleep the world of aeronautics. “The greatest pleasure life has to offer is the satisfaction that flows from participating in a difficult and constructive undertaking,” he explained….

It took only 10 years for Boeing to prove me wrong in asserting that its market position in civil aviation was impregnable. The decisive shift in corporate culture followed the acquisition of its principal US rival, McDonnell Douglas, in 1997. The transformation was exemplified by the CEO, Phil Condit. The company’s previous preoccupation with meeting “technological challenges of supreme magnitude” would, he told Business Week, now have to change. “We are going into a value-based environment where unit cost, return on investment and shareholder return are the measures by which you’ll be judged. That’s a big shift.”….

Obliquity gives rise to the profit-seeking paradox: the most profitable companies are not the most profit-oriented. ….

Unhappy businesses resemble one another: each successful company is successful in its own way. Business achievement depends on doing things that others cannot do – and still find difficult to do even after others have seen the benefits they bring to the imitators.

There’s a lot more in Kay’s meaty essay, but his general point is not hard to grasp: that success in challenging and dynamic circumstances requires commitment to high level goals and adaptability about the means, which includes discipline about questioning easy immediate moves. As we have seen, Trump does not stand for anything save his overlarge ego and relentless pursuit of grifting opportunities.

By Natalie Chen, Dennis Novy, and Diego Solórzan. Originally published at VoxEU

In 2018 and 2019, the US administration hiked tariffs on imports from China. This column shows that imports from Mexico partly filled the gap, leading to an export and employment surge in Mexico. Using highly disaggregated firm-level data on Mexican exports, combined with detailed employer-employee data, the authors find that US tariffs against China resulted in more employment and higher wages in the Mexican export sector, especially for lower-wage workers such as female, unskilled, and younger employees. The effects were concentrated in technology and skill-intensive manufacturing industries such as chemicals and automotives.

The global trade landscape is being reshaped. The most prominent fracture has been the US-China trade conflict. Prior to the latest round of tariffs imposed in 2025, the US had already imposed sweeping tariffs on imports from China in 2018 and 2019. As in 2025, China retaliated. Policymakers and firms were left assessing the impact of these policies that had not been witnessed in decades.

Recent research has begun to evaluate the global effects of the 2018/19 US-China tariffs. Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal (2022) review the economic costs to both the US and China. Utar et al. (2023) find that higher US tariffs against China had a positive effect on Mexican exporters involved in global value chains. Alfaro and Chor (2023) highlight the ‘Great Reallocation’ of global supply chains, including towards countries such as Mexico.

In this context, our new research contributes fresh evidence on how Mexico benefited through trade diversion – and what those changes meant for Mexican workers (Chen et al. 2025). We document how Mexico’s exports to the US rose in response to US tariffs against China. Our data allow us to track individual workers over time. We find positive labour market effects for Mexican workers, particularly among groups that are traditionally disadvantaged.

Can Protectionism Help Bystanders?

Protectionist trade policies are usually thought to benefit producers in the protected country at the expense of consumers and global efficiency. However, when a large economy like the US imposes tariffs on a major trade partner, the resulting reallocation of global trade can create opportunities for third-party exporters. This is known as trade diversion.

The theory of trade diversion dates back to Viner (1950), who noted that preferential trade agreements and tariff changes can shift trade. In our context, US tariffs against China made Chinese goods more expensive, creating an incentive for US importers to switch to other suppliers – such as Mexico.

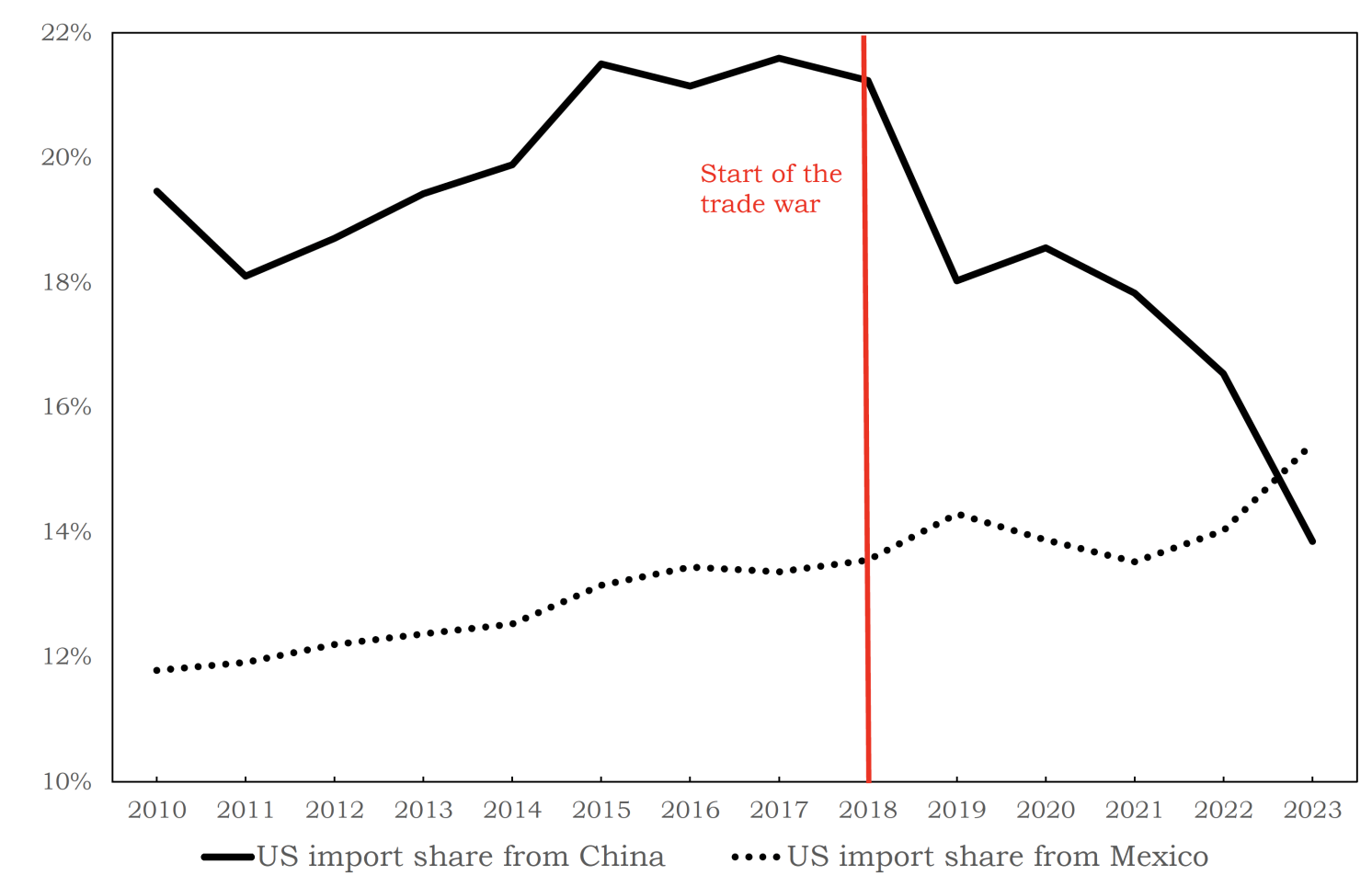

Figure 1 shows a striking pattern based on aggregate data. As the US import share from China declined following the imposition of tariffs in 2018/19, the import share from Mexico rose. This suggests that Mexico was able to fill part of the gap left by reduced Chinese exports to the US.

Figure 1 Shares of US goods imports from China and from Mexico in total US goods imports between 2010 and 2023 (%)

Note: Figure shows US goods imports from Mexico and China as a share of total US imports, 2010–2023.

Source: Direction of Trade Statistics of the International Monetary Fund.

The setting of the Mexican economy is particularly well suited for our purposes as there are strong reasons to believe that Mexican exports to the US increased in response to higher US tariffs against China. First, the costs for the US of diverting imports from China to Mexico are comparatively low due to the competitive labour costs and geographical proximity of Mexico – and therefore low transportation costs and short shipping times. Second, Mexico’s membership of NAFTA (replaced by the USMCA in 2020) makes it easier for the US to import more goods directly from Mexico than from other countries. Third, Mexico and China compete in the US market in similar product categories (Utar and Torres 2013).

Evidence From Firm-Level Trade Data

To investigate the trade diversion hypothesis, we use highly disaggregated Mexican firm-level export data at the 8-digit product level. We link these data to changes in US import tariffs on Chinese goods during the trade war period. We then examine how Mexican exports to the US responded.

We estimate that a 25 percentage point increase in US tariffs on Chinese goods raised Mexican exports to the US by 4.2%. This increase occurred through both higher export volumes (intensive margin) and a larger number of products exported (extensive margin).

From trade to workers: Labour market outcomes

Trade diversion also has important implications for workers. To understand the labour market effects, we combine our firm-level export data with detailed Mexican matched employer-employee data. This allows us to track changes in employment and wages at the worker and firm levels over time.

We estimate that a 1% increase in Mexican firm-level exports to the US driven by higher US tariffs against China increased wages by 0.103% on average. Strikingly, these wage gains were not evenly distributed. Wage increases were concentrated among female, unskilled, younger, and non-permanently insured workers who typically receive lower wages than male, skilled, older, and permanently insured workers. For instance, we find that women experienced a wage increase about double the size of the increase for men.

This is a key result. Our findings suggest that trade diversion in this setting had an equalising effect within firms. That is, positive export shocks benefited lower-wage workers more than higher-wage workers, reducing within-firm wage inequality.

Workforce Composition Effects

We then run regressions at the firm level. We find that trade diversion had a positive effect on employment and a negative effect on mean wages. Specifically, a 1% increase in firm-level US exports driven by higher US tariffs against China increased employment by 0.146% and reduced mean wages by 0.197%. These effects were concentrated in technology and skill-intensive manufacturing industries such as “Chemicals, rubber, and plastics” and “Machinery and automotive.”

We argue that the employment increase is consistent with firms increasing production in order to satisfy the surge in export demand induced by higher US tariffs. The fall in the mean wage resulted from a composition effect. As firms increased employment, they disproportionately hired low-wage workers including female, unskilled, younger, and non-permanently insured workers.

Policy Implications

Our results carry important implications. First, third-country spillovers from large-country trade policy changes in 2018/19 were real and quantitatively important. Since the US and China were two major economies engaged in a trade conflict, the effects rippled across the globe – creating both disruption and opportunities.

Second, the labour market benefits in Mexico were skewed toward groups that are traditionally disadvantaged. This points to an impact of trade diversion that reduced inequality within firms.

Finally, for the most recent trade conflict that started in 2025, we should also expect diversion effects for trade and employment in third countries. But this time around, the US administration targeted a larger number of countries and many more industries with more uncertainty regarding the outcome. The eventual impact is likely going to be more complex.

Authors’ note: The results of this study do not necessarily reflect official positions of Banco de México.

See original post for references

Thanks for this post.

‘The map is not the terrain.’

It was to encourage would be migrants to stay south of the border. That was the plan…really…

Thank you very much for this, since I’ve been carrying out similar research focusing on the clothing assembly industry in CAFTA-DR countries. I will be mining their study for my bibliography/methodology.