Yves here. On the one hand, this article sets forth a strategy for preserving something approaching serviceable health care in parts of the US, which may wind up being “pockets of the US”: the more affluent, more science-friendly blue states, which are also where the better US med schools are concentrated. On the other hand, there’s also a lot of conventional wisdom, some of which readers are likely to contest.

I hope IM Doc can weigh in on two bits that set my teeth on edge. The first:

General AI models like Claude, ChatGPT, and Gemini are now achieving diagnostic accuracy rates above 90%. For comparison, the average physician gets it right only about 20% of the time, and even top-performing doctors cap out around 40%.

This seems impossible in light of the train wreck that IM Doc has reported in his hospital with AI transcriptions of session notes. They aren’t just “at the margin” wrong. They are often wildly wrong and include hallucinations. He says he has to spend a lot of time correcting them, they can’t be assumed to be accurate, and that many of his colleagues don’t bother.

To achieve that 90% claim, I suspect that the testing was done in cherry-picked circumstances, and/or that the promoters used the same trick that retail fund manager have long used: Start 20 funds. Pick the one that does the best (randomly, at least one will) and use that track record as a basis for fundraising. Here you could see 20 AI diagnosis v. MD tests, with the best chosen and falsely depicted as representative.

Mind you, I do think it is possible for AI to beat doctors on narrow diagnostics, like reading imaging. But that’s not at all like throwing a general purpose LLM at patients.

And that’s also omitting a factor that IM Doc regularly stresses: that doctors (or at least well trained ones) pick up a lot by observing the patient for things like skin color, energy level, speech patterns, and changes in them over time.

A second wowser:

For example, if the surveillance system detects rising viral loads, AI can recommend specific mitigation steps — like indoor air quality mandates for schools.

*Pounds head on desk*

Is this a joke? Are public health officials so stoopid they need AI to tell them that better ventilation in schools is a key measure to prevent infection, and not after the horse has left the barn in the form of rising hospitalizations or measurable cooties in the air? Or is it that simple measures like Corsi boxes are still so controversial that they can’t be recommended unless an AI oracle says so?

By Lynn Parramore, Senior Research Analyst at the Institute for New Economic Thinking. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

America’s healthcare system is collapsing — but not evenly. It’s fracturing into separate realities.

Call it MADA: Making America Divided Again.

Once held together by a strong federal backbone, public health in the U.S. is now tearing into a patchwork of wildly unequal systems. From vaccine access to basic care, your ZIP code may determine whether you live. Or die.

As federal agencies weaken under political interference and anti-science leadership, states are left to pick up the pieces.

Phillip Alvelda, a former DARPA program manager in the office that helped pioneer synthetic biology and mRNA vaccine technology, argues that some states, especially science-driven “blue states,” have the tools, the talent, and the financial wherewithal to build their own public health infrastructure.

This includes real-time disease surveillance, universal care, and even the development of next-generation vaccines. Whether they seize this opportunity remains to be seen. Meanwhile, other states are moving in the opposite direction — dismantling protections, slashing funding, and aligning with private interests that put profit ahead of public health.

In a conversation with the Institute for New Economic Thinking, Alvelda explains how this crisis presents a rare chance: to rebuild a system that is leaner, smarter, and truly centered on care rather than profit.

Lynn Parramore: Let’s start with the current state of America’s public health. What concerns you most right now?

Phillip Alvelda: There are so many assaults on different fronts. But perhaps the most significant change is the claw back of Medicare and Medicaid support. An estimated 17 million people could lose their health insurance.

But that number underrepresents the impact. For many, losing health insurance means losing access to care altogether. These are vulnerable populations with no other safety nets. And now there’s talk in Congress about requiring proof of work to receive coverage. It’s a draconian move that amounts to a money grab. People will die without care.

We’re also seeing changes in leadership at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which are now pushing anti-science, anti-vaccine policies. They’ve fired many experienced third-party advisors and replaced them with people who have little experience and long-standing anti-vax positions. The new leadership has already made access to COVID vaccines more difficult and expensive. They’ve removed distribution requirements and failed to approve important drugs like Novavax.

We’re seeing a coordinated campaign against one of the most effective public health interventions in human history — vaccination. The consequences are deadly.

LP: Given the collapse of federal public health infrastructure, do you think states might effectively step in to build the kind of real-time health monitoring systems we need for managing ongoing and future health crises?

PA: I often refer to this as the surveillance piece of public health. Effective surveillance requires infrastructure, clear policy, and enforcement. It’s not that expensive, but it is absolutely essential.

Unfortunately, we’re now up against an anti-science movement that actively resists data collection because it might contradict their political agendas. The CDC has cut funding, stopped maintaining key websites, and allowed once-impressive national surveillance systems to collapse.

But yes, states can and should pick up the slack. Wastewater testing, hospital reporting — these are affordable, manageable systems. States like California already have the infrastructure and capacity to implement them.

This isn’t just about COVID anymore; we’re also facing rising threats like bird flu and measles due to weakened vaccination efforts. To respond effectively, states need to maintain their own reporting requirements. And if only the science-oriented “blue states” have the political will, then perhaps it’s time to form a coalition — a networked public health system to safeguard against future crises.

Our once-envied institutions, like the CDC and HHS, have lost independence, but this is an opportunity to build new agencies, funded and governed by the states. Perhaps a California CDC, a New York CDC, or a regional blue-state CDC, and so on.

LP: That makes sense. States like California and New York already have strong public health departments.

PA: Exactly. These states live and die by public health. The economic impact of long COVID alone is already visible.

California, New York, Oregon, Washington, Massachusetts — these states absolutely have the capacity to lead. And they can also stand up to the insurance industry. A state can decide what it wants to pay for and how.

This is urgent. We need to act now — recruit the right people, who, by the way, are newly unemployed due to federal cuts.

LP: So the talent is there—it’s just a matter of policy and funding?

PA: Yes. We need state-level policy leaders willing to back it and budget for it. Surveillance is just one area. We also need broader bio-surveillance.

LP: Are you concerned about the risks posed by biological research or virus development efforts in other countries?

PA: Absolutely. The technology needed to make dangerous viruses is not very advanced – all you need is basic lab equipment and a few knowledgeable people. The global impact of COVID has surpassed that of nuclear weapons. Yet we spend far more on preventing nuclear accidents than on preventing biological disasters.

LP: Viruses and diseases don’t respect state lines. If we end up with essentially separate public health systems—one for red states and another for blue—with different rules for regulation, surveillance, and response, what does that mean for the country as a whole?

PA: That’s exactly the danger of the “leave it to the states” approach. We’ve already seen the consequences — fatality rates as much as seven times higher in areas with low vaccination rates and underfunded health systems.

We need state-level public health systems that are universal, accessible, and focused on prevention. Wealthier states must lead the way, because when one part of the country is vulnerable, we’re all at risk.

LP: Could blue states take the lead in developing next-generation vaccines—like the nasal mucosal vaccines widely held to be especially effective at stopping COVID infections?

PA: They absolutely could, and they should. States like California, with world-class research institutions and a thriving biotech sector, are uniquely positioned to lead the next wave of vaccine innovation. Nasal vaccines, in particular, could be a game-changer.

If the federal government won’t lead, states have to. That means building and maintaining the entire vaccine development pipeline, from education and research to clinical trials and manufacturing.

Right now, that pipeline is under threat. Funding for advanced training programs has been slashed by nearly 50%, and we’re actively discouraging the international talent that has long powered American science.

California, for example, should invest directly in universities like UC Berkeley and Stanford, and support in-state clinical trials. We may not be able to preserve the full national infrastructure, but we can build strong, self-sustaining regional capacity. The stakes are too high to wait.

LP: So, potentially, a resident of California could get access to a vaccine that isn’t even available in another state?

PA: It’s already happening. Some states have stopped stocking key vaccines entirely. We’ve effectively fractured into multiple healthcare systems, where your access to lifesaving medicine depends on where you live. It’s a dangerous precedent, and it’s accelerating.

Poor healthcare in under-resourced states isn’t new, but it’s more visible now, thanks to broader media coverage and national crises like COVID. The Trump administration accelerated the dismantling of the safety net. Rural hospitals are shutting down. Public health infrastructure is collapsing. More and more, the system is designed to serve the wealthy—while abandoning workers and the vulnerable.

We’re already seeing the cost: the life expectancy gap between wealthy white Americans and poor Black Americans is now about seven years. It’s even worse for Native Americans.

That’s not just a health disparity. It’s a national failure.

LP: Let’s talk about AI. What role could it play in addressing the failures of our healthcare system?

PA: There’s huge potential, though not necessarily in the ways people expect. While many worry about AI replacing jobs, it’s already outperforming doctors in one of the most critical areas: diagnostics.

General AI models like Claude, ChatGPT, and Gemini are now achieving diagnostic accuracy rates above 90%. For comparison, the average physician gets it right only about 20% of the time, and even top-performing doctors cap out around 40%. That’s a staggering gap — and a massive opportunity to expand access, improve outcomes, and reduce medical errors, especially in underserved communities.

Consider the case of long COVID. Most clinicians are out of date on it, haven’t read the latest papers, and so on. Patient-led treatment groups are doing a better job directing clinical trials. AI models, with access to the latest research, are proving more helpful than clinicians in treating long COVID.

LP: Could AI also help with public health surveillance?

PA: Yes. It can help analyze trends, predict outbreaks, and guide policy decisions in response to real-time surveillance data. For example, if the surveillance system detects rising viral loads, AI can recommend specific mitigation steps — like indoor air quality mandates for schools.

LP: Paint a picture of your vision for a better healthcare future. What does it look like?

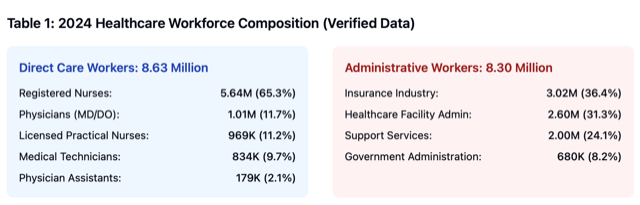

PA: First, we have to confront the reality: our healthcare system is driven by profit, not care. It’s bloated with administrators, insurance middlemen, and pharmacy benefit managers—all extracting value without delivering any actual healthcare.

Health insurance isn’t healthcare—it’s a financial product designed to limit access and deny claims. The ratio of administrators to care providers is absurd. We’re spending more and getting less.

If the federal system continues to break down, we have a rare opportunity to build something better from the ground up. Strip away the bureaucracy. Fund doctors and nurses directly. Deliver real care to everyone — not just coverage, but actual services that improve lives.

We’d save money. We’d save lives. It’s time to build healthcare, not health insurance.

LP: How effective do you think private integrated care models like Kaiser Permanente really are? Do they offer a path toward better healthcare, or do they share some of the same systemic problems as the broader industry?

PA: Kaiser is probably one of the more efficient ones, but don’t mistake their giant buildings for good governance.

They suffer from the same disease: they claim, “We’re only generating 3% profit,” but they grew 20% last year. How did they grow? Not in doctors and nurses. They grew in administrators and overhead. They’re becoming larger and more impactful for shareholders, but less impactful for actual care.

Kaiser is very good at managing and minimizing the cost of care — with a huge apparatus generating administrative overhead and revenue. So yes, they fall into the same category as others.

Another example would be pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). PBMs were originally designed to stand between consumers and pharmaceutical companies, using collective bargaining and economies of scale to negotiate better prices and pass savings on to the consumer. But once pharma companies realized what was happening, they started acquiring PBMs. And then PBMs were turned against the consumer, to extract more money on behalf of pharma.

PBMs became one of the most rapacious tools of the last few decades. Several states, like Oregon, have now cracked down on them for that reason. But we still have rapacious pharmaceutical companies charging hundreds of dollars for things like insulin that cost just a few dollars to make.

LP: States like Oregon are also restricting private equity from getting involved in medical practices. Do you see this kind of state-level action as a promising step?

PA: Absolutely. I’d like to see more states follow suit. The problem with private equity in healthcare is that it leverages financial tactics to extract increasing profits while cutting back on actual services. This isn’t just a few bad actors. It’s a systemic issue that demands broad, meaningful regulation, not just piecemeal bans.

We need clear, enforceable rules that ensure healthcare funds go directly to patient care — not bloated administration, overhead, or systems designed to deny coverage.

LP: Would you support banning private equity altogether from healthcare?

PA: Honestly, yes. That would be my favorite outcome. But I also recognize that private equity can play a role. The real question is: What limits do we place on profitability? And where can these firms contribute by building systems that provide fair market value?

There are responsible examples. Take Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs — it’s an open, transparent company that sells medications at a fair price and exposes the entire value chain. It’s disrupting the big pharma model, and they hate it.

Unplugging healthcare from the profit machine is essential. Many of these companies market themselves as “just making 3% profit,” but that’s after massive reinvestment in technology, acquisitions, and expansion. To go back to Kaiser, they were building new campuses in Oakland during the height of the pandemic, when everything else was shutting down. And they had their most profitable run ever during that period—even as Americans were dying in record numbers.

This system has created a parasite that’s feeding off Americans, and it’s gotten too big to bear.

The federal government is stepping back, but the states can step forward.

LP: Is there anything you wish the media were focusing on right now but aren’t?

PA: Absolutely. They need to expose how the federal government is systematically dismantling the very institutions that hold this nation together. This isn’t just policy. It’s a fundamental attack on our unity.

We call ourselves the United States because together we are stronger. But that bond is fraying fast.

Rights and access to basic services — abortion, LGBTQ+ protections, healthcare, clean air, education — are no longer universal. They depend on your ZIP code. We’re unraveling the very fabric that binds us as a nation.

This feels like the unresolved wounds of the Civil War reopening, with the Confederacy’s ideology rising again: stripping protections from the poor, suppressing wages, denying education and healthcare. The Supreme Court is pushing these battles back to the states, just like before the civil rights movement. That’s precisely why we established federal agencies — to protect those who states historically abandoned.

Now, we’re watching all that progress unwind. The Confederacy is returning.

LP: You could imagine figures like John C. Calhoun smiling at this.

PA: Absolutely. But there is hope. Strong, responsible leadership exists in many blue states. The problem is the Democratic establishment hasn’t yet grasped that this is an existential fight for democracy itself. Clinging to old norms and moral posturing won’t be enough. We need bold, decisive action.

Here’s the bright spot: California is the fourth-largest economy in the world. It has the power to act independently—in healthcare, education, disease control, public policy—even if the federal government collapses.

What we need now are leaders like Newsom, Hochul, and others to seize that moment. To build the future by making states strong, independent actors stepping into the void left behind.

Economic Analysis and Policy Implications

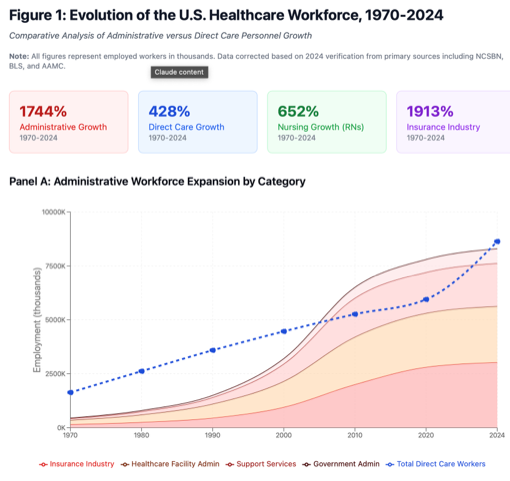

Administrative Cost Burden

Administrative spending represents 34.2% of total healthcare expenditures, approximately $1.2 trillion annually. This far exceeds administrative costs in other developed healthcare systems (Himmelstein et al., 2020).

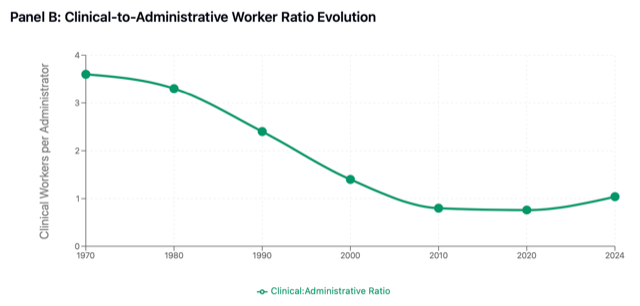

Workforce Structural Shift

The U.S. healthcare system evolved from 3.6 clinical workers per administrator (1970) to near parity by 2024, representing a fundamental restructuring of healthcare labor allocation.

Nursing Workforce Expansion

Registered nurse employment reached 5.64 million in 2024, 61% higher than previous projections, now representing 33% of the total healthcare workforce and driving much of the sector’s employment growth.

Insurance Sector Transformation

Health insurance industry employment expanded 1,913% from 1970-2024, becoming the largest single administrative category and employing more workers than physicians and physician assistants combined.

See original post for references

IMO the possibility of Balkanization happening in this country went up when DOGE was cutting swaths of the Federal Government and no one in the Republican Party attempted to stop it.

@kj1313 — “IMO the possibility of Balkanization happening in this country went up when DOGE was cutting swaths of the Federal Government and” NO ONE stopped it.

There. Fixed it for ya.

+100%

“Given the collapse of federal public health infrastructure, do you think states might effectively step in to build the kind of real-time health monitoring systems we need for managing ongoing and future health crises?”

I pray to god not. The fundamental issue is that states are not currency issuers. Adjusted for inflation, we have too many citizens sharing an ever shrinking slice of the economic pie. Given that reality there are only two options, (1) the currency issuer assumes financial responsibility to allow these people to consume a product they cannot afford and allow the people who are employed in this sector to disconnect their economic realty from the people they serve, or (2) drive wages and costs down in the healthcare sector such that well educated doctors, administrators, and scientists have their wages crushed to reflect the economic realty of the customer they serve. Having a non-currency issuing state take over healthcare without addressing economic issues or healthcare delivery cost is a recipe for widespread poverty.

I am a KP patient – “member” – in the MidAtlantic region, and wish to point out that because of the way it is structured there are no “shareholders”, contrary to what Avelda says.

As for Kaiser “building new campuses in Oakland during the height of the pandemic, when everything else was shutting down” – this expansion’s coinciding with “Americans dying in record numbers” seems coincidental. Does he think that it would have been better to postpone the construction? Maybe it would have – or maybe not – but what does it have to do with the how the healthcare system is run in general?

As a KP member myself, I have to say that Kaiser has too much money squirreled away in fancy real estate, while denying or delaying too much care. The Justice Department found them guilty of charging for care not actually given.

I like the parts where states’ healthcare infrastructure are expected to be fully functional 24-7 when in crisis because of floods and fires and storms.

And how does this work in cities that straddle state lines?

First, it seems like this DARPA project manager is envisioning a secession and civil war, which is a potential outcome of the “coalition” advocated and thinking and actions in that vein. The effects of institutional collapse, and the public health consequences of such an event would be immense. Those who took an oath to first, do no harm ought to keep that in mind.

Second, to Yves point in the intro about diagnostics, a second-order acquaintance who has worked on tech infrastructure for healthcare at the federal level is working on a subscription-based AI personal health model, supposedly to undercut health insurance profits. You’d pee in a cup, the AI would analyze it and use it, along with a constant data stream from wearables, to diagnose conditions and prescribe treatment. No human fact-checking to add labor costs. One reason this is thought by this person to be more accurate in diagnoses is that human practitioners are sometimes required to have patients try less effective, but cheaper treatments before going to the preferred option, a requirement to which this AI presumably wouldn’t be subject.

No proposed roads forward sound good to me, between the obvliviousness to a collective public health perspective, the de-skilling of doctors and nurses, the administrative bloat and profiteering, private equity renting hospital land back to the hospital, the questionable ethics and efficacy of relying on for-profit pharmaceutical companies to develop our treatments, the data security concerns, the side-effects: it’s all bad. One needs to be a strong advocate for oneself in hospital environments particularly, but with medical practitioners in general to avoid personal disaster. I know someone who works in medicine who says that there’s more dignity, and less trouble in just getting sick and dying than in attempting to work your way through our healthcare system.

All of these strategies Phillip Alvelda puts forth assumes states will even have the freedom to impose their own standards and/or be able to form and keep a compact to enforce them. If Trump is willing to sue states and overturn waivers that try to exceed federal standards for vehicle emissions, and also played politics with withholding respirators, ventilators, and aid to ‘Blue’ states during COVID, then I bet that any attempt by these states to form some type of healthcare system together will be swiftly shot down by the Trump administration, assisted by the Supreme Court’s deference to him.

As a radiologist I keep being told my job is in jeopardy yet all I see are increasing volumes decreasing pay and severe shortage of doctors. If I was only 40% accurate I’d be sued so many times and lose my license. My decisions are there in the chart forever to be critiqued by all. All the AI tools I’ve seen while sometimes useful are at best a net loss of time for me having to double check it’s work. It’s like having a resident in training but more limited. Even apparently simple things that LLMs should excel at like automated impression generation tends to produce grammatically and factually correct prose that is overly verbose, obtuse, and not tailored towards the ordering physicians questions. It’s quite obvious which of my partners use it as their impressions have become paragraph sized garbage rather than suscinct answers.

Regardless, I foresee the trillion dollar AI boondoggle will force itself into many ill fitting use cases due to marketing and clueless admin.

I’m glad I’m near end of career and will offer bespoke analog human interpretation when and if the AI apocalypse comes.

Thank you!

I think “AI” image analysis has a role in initial radiography screening, but not as the final arbiter. But this is analytic “AI”, not Gen AI using predictive LLMs. Image analysis is a pretty well defined and well covered process, with a pretty long history of success. It can be exhaustive in its coverage, whereas humans tend to be less so.

HOW it would actually be implemented, and how it would act as a first filter is something for radiologists to weigh in on.

AI summaries of visit notes will ALWAYS be a complete disaster, since it’s generative and probabilistic. As soon as the inevitable corpus (sorry!) of fatalities due to bad notes becomes apparent, then it’ll be interesting to see what happens…

If you had read the piece carefully, Alvelda was advocating for the use of LLMs like ChatGPT in diagnosis, not what you call analytic AI.

Yves, I’m with you that 90% diagnostic accuracy is a gross exaggeration.

I have heard that AI is really good at finding cancer and the like by viewing medical imaging… it can identify the subtle differences between benign tumors and not much better than the best human Drs, but that’s just imaging data. But that is not the same as you going into the Drs office with a problem and AI giving you a diagnosis. You’d be better off arranging your funeral along with getting an AI diagnosis if AI was your GP.

The key missing data is that someone ELSE ordered the imaging work. The data fed to the AI model only had to correctly predict the cancer (or other imaging related diagnosis) AFTER the patient had been put into the pool with a prior diagnostic concern. It did not have to diagnose patients from a random group of people showing up at the Drs office.

On top of that models tend to over perform on training data, because it has been pre-cleaned of outliers or records with missing information… the training data had to have KNOWN that the patient had cancer or not in the final assessment. Any person who died before being confirmed or otherwise had missing confirmational data would NOT be included in your training data set.

I would find it laughable that there exists any AI driven “diagnostic” capability to take a patient from a waiting room and correctly diagnose them of anything 90% of the time. Yes it may be right 90% of the time in a VERY VERY narrowly trained setting, but no one actually goes to the Drs office in such a real setting.

New Mexico has been working on this for years it is blocked in the legislature.

I’m guessing that the “diagnostic accuracy rates” are measured by giving AI tools and medical providers a specified list of symptoms, blood tests, genetic information and other relevant information then asking for a diagnosis. An expert panel determines correctness and the rates are established and comparisons made. So the hard part of diagnosis is assumed as a given – knowing what tests to run, questions to ask, etc. In my experience, AIs are not as nearly good as humans at knowing what to ask. I’d like to see how they’d perform with live patients and poorly described symptoms.

That said, LLMs have improved dramatically over the past six months – some (medGamma, a local LLM from Google) are now fine tuned on medical texts and reinforced by panels of medical experts. If you give them relevant test results, symptoms, etc, these newest AIs can probably outperform typical practitioners, especially if the case is complex or highly complex. But that assumes the materials they’ve been trained on are good (not fudged industry studies) and that experts can really determine “correctness.”

If you’re not sure about the quality of US-based AI medical training, you can use one trained in China or France. It’s interesting to see the differences in medical recommendations for the same conditions. Not surprisingly, the Chinese models tend to be more tolerant of alternative approaches such as TCM.

For privacy, I download the local llama-based LLMs and run them on my own (good) hardware. The latest provide far more useful information than my typical 15-minute nurse practitioner and specialist visits. But without good context (tests, symptoms, genetics,…) the ones I’ve used can’t help much.

AI 90% accuracy is so far from our knowledge level, it makes me suspect all messy, multiple diagnosis and atypical presenting patients were dropped (not sure what study they are quoting). Figuring which abnormalities are actually casing a health issue, and best management, is much harder than pointing to a high cholesterol level and making such a diagnosis.

If states outlaw (or tax prohibitively) PBM’s, allow patients to purchase meds from any developed country, enforce insurer anti-monopoly and contract breeches (with high penalties), and take back management of Medicaid, the savings could fund significant public health. Physicians are increasingly pulling out of managed care, even Medicare, so a well run state Medicaid (lacking managed care hassles) may result in real improved effectiveness, and worker health. We know Medicare is MUCH cheaper than insurer run Medicare Advantage – similar savings would be expected with Medicaid.

Higher taxation of ultra-processed foods, perhaps while subsidizing local healthier foods (or shifting the tax to ultra-processed, and removing subsidies to ultra-processed)) might also help. With the federal system flailing, and costs hurting business, oligarchs and workers, I expect we could see some interesting experimentation and lawsuits.

“Strong, responsible leadership exists in many blue states”

Where? live in one (OR) and I’m not seeing it.

Michigan here, and I’m not sure what we are. My area would be the most affluent in the state, but for my local district, where I quite fit in. A NJ size portion of MI is blue, but to what effect?

The Confederacy is returning.

I did get something from this analysis.

Minnesota State Senator John Marty has developed and printed a state health plan. The plan is at:

http://www.mnhealthplan.org.

It is also available as trade paperback from Amazon.

Everybody in, nobody out. And runs without corporate overload.

It is delusional to posit that NY and Cali can lead the way to reinvent healthcare. Recall no further the BOTH states had the democrats promising statewide single payer. Until they had supermajorities and governors like Cuomo and Newsom. Then recall the COVID leadership of Cuomo.

There are *some* positive things with public health in New York State. But they system is very broken outside of Manhattan, Nassau and Westchester.

This is wishful thinking at best.

The idea that these massive, national-scale companies are going to be restrained at the state level where they can leverage the federal government to protect their bottomline is naive. Why wouldn’t they? As a matter of fact, if they did not try and subvert the states intentions, would they be meeting their responsibility to their shareholders?

First of all, I am involved with students from all kinds of school from our most elite to our big state schools. I would strongly disagree with your assertion that the big elite blue state schools – either private or public – are better thinkers and physicians. Nothing could be further from the truth. The lack of critical thinking skills and the use of elementary logic is completely lacking in many kids from our elite universities. Many months ago, I asked one of the better trained elite medical students what was their opinion of this observation and I was told that lines of thought in human behavior, logic, and medical ethics were thought to be so profoundly corrupted by racism, misogyny and bigotry that they are no longer even remotely taken seriously. I have not had the heart to delve into this further other than to realize with each passing month that it seems to be far more common than not the more blue and the more elite the student’s background. Trust me, I never thought I would have to say that, but I also can not ignore what is going on around me. Looking to big blue states, institutions and universities for the answers to our problems at this point is becoming more of a fools’ errand every day.

With regard to AI in my daily life that I am being forced to use. I would preface this by stating emphatically, I have no training in AI or even computers. I have no idea what is behind the curtain. So I am going to be completely unhelpful in any kind of technical discussion. However, do I ever know how it is being used and how it is interfacing with medical practice.

I directly work with 2 very different ways that AI is being used and am somewhat affected by yet another 3rd way. We are constantly told this is “AI” – however, the term is so overused now that I have no idea if it is AI or not.

Firstly, it is used in the generation of our notes. We turn on a recording device in patient visits, the data is sent off somewhere and in a few minutes a fully integrated note appears on our screen to be signed off on as the official record. As I have explained before, these are fraught with errors. We often have made up diagnoses, made up hospitals, pharmacies, etc, made up recent testing, and made up chart results. When I mean made up – I mean made up. The vast majority of the time, absolutely nothing about these issues was ever discussed in the visit. It is often so ludicrous that I have no idea where it even comes from. But many times it is very accurate. Unfortunately there is another really bad habit – we often discuss POTENTIAL problems and diagnoses in visits – and almost all of the time – these potential issues are listed in the problem list and notes as actually being really present. This is not good at all. All kinds of mischief can occur down the line if this kind of thing is not corrected before signing. And that is just the problem, there are so many errors that a) I know I am missing things – and b) it takes a LOT of time to correct.

2) More recently, “AI” has been introduced to query us about our assessment and plan and to “help” us with diagnosis and to suggest all kinds of tests and avenues to explore. As a clinician of 35 years, I have been absolutely horrified the majority of the time where the AI is leading the clinician. Legions of unnecessary tests, suggesting things to the patients about their health that would absolutely freak them out, just off the wall stuff. Even more scary, I have now conducted two experiments whereby recent case studies of the MGH have been presented to me ( I have no idea what the concluding answers are) and the computer in the guise of a fake patient – data entered by colleagues…….OMG – it is absolutely frightening what it comes up with. I have noted another problem…….once it goes down the wrong path, often very early in the case, it refuses to rethink or regroup – it STAYS on the wrong path. I have then started to test things by myself on fake patient records – just to see what it would do. For example, internal medicine is PATTERN RECOGNITION. This is drilled into the head from day 1. Many many of the board questions are testing if you recognize these patterns or not. So, the other day, I placed on a fake patient chart the presentation of fever, anemia, renal insufficiency, and back pain on a 68 year old male ( again made up). THIS IS A PATTERN – the very first thing that should come to an internist mind is MULTIPLE MYELOMA. The AI spewed out 6 possible things – the highest ranked were UTI and prostate cancer. Myeloma was not on the list. I then added the labs. We added proteinuria, hypercalcemia, and a creat of 2.1. It still was on the UTI train. I then added the PSA being normal – and it did not drop out prostate cancer. Instead – it suggested I order a prostate MRI. I then placed the labs that the patient had a monoclonal IgG elevation. This is THE red alert for myeloma – and NOTHING. It would not reconsider – it would not change its mind. I know these things. I have been doing this for 35 years. I was raised in medicine without a computer in sight – just your brain and wits. The same cannot be said for my younger colleagues or God forbid the nurse practitioners, etc. It is just horrifying what can happen. I AM TRAINED TO THINK FOR MYSELF – TO GO OVER THINGS WITH PATIENTS AGAIN AND AGAIN UNTIL WE GET IT RIGHT – AND TO SELF-CORRECT MISTAKES AND THE WRONG PATH. “AI” does not do that, it is a disaster waiting to happen, and I am not sure how long it will take, if ever, before being safe.

3) This has not happened to me – at least yet – but AI is now being used for billing and upcoding – every shred of coding it can. But as I have asked so many times – IF THE NOTES GENERATED BY AI ARE NOT CORRECT THE MAJORITY OF THE TIME – How on earth can any system use those notes for billing and have it be correct. Truly scary.

The 90% thing is absolutely laughable. This is all so concerning to me. And seems to be a real disaster in the making. I do not know what else to say.

I very much appreciate your detailed comments on the AI issues and suspect I will wind up hoisting them into posts later. Even though I am still seeing a couple of my NYC MDs (to keep up relationships just in case), they are in solo practices and so not having AI forced on them by the adminisphere.

However, I hate to tell you but I have seen the caliber of the doctors that came out of the University of Alabama’s med school, considered to be the best in the South. Even with good referrals (my parents had lived there nearly 50 years, had two close friends on the UAB med school faculty), I wound up staying with NYC doctors despite the cost of regular trips (and the not-great position of not having a local doctor in case I had to go to the ER, which fortunately never happened). So I beg to differ with your view of elite v. reputable but non-elite programs. For instance, I was referred to the supposedly best orthopedist in Birmingham, and he wasn’t even very good at diagnosis; he basically dialed his evaluation in when I have long been an outlier case. And this is a football town, so it’s not as if there’s not a lot of procedures done. Similarly, there was no one remotely as good in the pool there as the NYC surgeon and gyn and other doctors I had deal with my Covid vaccine injury. And for my hip replacement, recall you recommend only Stanford docs as an alternative to the NYC referrals I had.

I could give the long form story about how my father’s rheumatologist basically killed him by giving him an experimental treatment (n=8 in the only paper on it!!!) to which he had a horrible reaction. I would meet with my mother’s MD who had a reputation among the doctors at the University of Alabama as being a good diagnostician. I found him to be uninterested in some of her issues, that she was a very old woman and what do you expect? Similarly, when she was hospitalized, the care was dreadful and the doctors were negligent, having settled on an incorrect diagnosis and continuing to administer debilitating tests to try to prove it out.

And I did find an very good dentist and a good oral surgeon and a terrific endodontist in the South, to whom I had been going before I moved to the South, so it is not as if I have a prejudice against Southern practitioners generally.

Similarly, a colleague (former Bschool prof) has been teaching a special course on the history of medical advances in med schools. He teaches case method and so interacts extensively with his students. He volunteered that he gets much more thoughtful and insightful questions from the students at elite programs than elsewhere.

I suspect adverse selection with the Ivy students you are seeing. You said a big draw for them to come to your hospital was that it is in a resort area.

Now I can accept given the crapification of everything that the gap between elite school students and those in other programs has narrowed substantially.

As I keep saying, AI is not intelligent!

I had to google it, but it appears Multiple Myeloma (MM) is a rare condition. Given what you said about how AI responded I have a suspicion as to why it was so stuck any diagnosis by MM.

My suspicion is that the AI model probably can’t predict MM beyond a random chance (or near random chance). I bet if you did the same thing for a couple other fairly rare illnesses you’d get equally bad results.

Here’s the deal or at least a description of the type of problem the AI model probably has deep in its core… I do a lot of marketing modeling and a common type is campaign response prediction – will a targeted person respond or not respond. When you are building and training such models you target variable is usually made up of Yes’s and No’s (1 and 0), however the typical response rate in marketing can be very low… 1 or 2% of your total. If you use ALL of your prior campaign data, which could be 10,000’s or 100,000’s of records the model becomes very efficient at predicting No’s but likely can’t predict Yes’s very well if at all. You need to build you training data to be outsized with Yes’s.

Absent building separate models for any non-average patient diagnosis, it would seem quite probable that any rare illness will frequently get undiagnosed because all other options are statistically stronger. My understanding is that most AI systems use lots of what we call Neural Network models for processing the probability statistics. They are inherently black boxes and almost impossible to understand what is going on which I would suspect makes them very difficult to test accuracies for rare (or read outlier) diagnoses and probably even more difficult to correct.

I suspect one of the reasons you have been taught to observe the patterns is because lots of people come into the Drs office with some subset combination of fever, anemia, renal insufficiency, and back pain and they don’t have MM. Your training tells you this is a special combination; your intelligence tells you to ignore the fact that the probability of many other illnesses is much higher. AI doesn’t have that intelligence and it would need special training to ensure that that pattern combination overruled the other statistical outputs it is also computing.