This article examines how the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) evolved from the most imaginative and consequential technological incubator in the United States to an agency constrained by political caution, industrial decline, and bureaucratic inertia. By contrasting its golden age—marked by ARPANET, stealth, GPS, and breakthrough computing—with its current era of unfielded prototypes and abandoned systems, we explore what changed in DARPA’s environment and why the agency no longer produces world-altering capabilities. The analysis centers on three structural failures: political interference, industrial risk aversion, and perverse incentives that reward programs for never reaching completion.

DARPA was created in 1958 in the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s launch of the Sputnik satellite. DARPA’s mission was to restore U.S. technological leadership and ensure that the U.S. defined the frontiers of defense innovation. Operating outside traditional military service bureaucracy, it was empowered to make high-risk bets on long-horizon research, aiming not to refine existing systems but to invent entirely new categories of military capability.

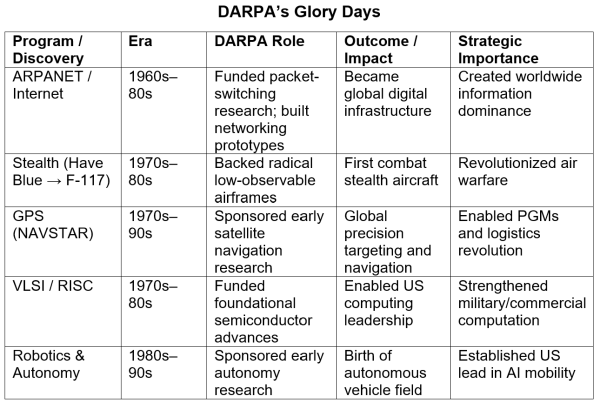

DARPA’s Golden Age

DARPA’s early decades from the 1960s through the 1990s were defined by an extraordinary ability to convert theoretical research concepts into functioning, world-changing systems. At the height of the Cold War, the United States maintained a dense constellation of industrial laboratories, elite universities, and high-talent engineering shops that could absorb DARPA’s experimental vision and transform it into working infrastructure.

ARPANET, the ancestor of the modern Internet, remains the clearest example: a long-horizon bet on networked packet switching communications that matured over subsequent decades into the public Internet, the backbone of the global digital economy. In this era, DARPA’s fundamental advantage was not talent, money, or secrecy, but its tight coupling to an industrial ecosystem capable of absorbing radical ideas and turning them into deployed military assets; it is a capability the U.S. no longer possesses.

ARPANET IMP – the start of something big

Have Blue prototype – precursor to F117

Political Restriction

DARPA’s mandate changed dramatically in the early 1990s when director Craig Fields was removed for expanding the agency’s work into dual-use, commercially relevant technologies, especially semiconductors. His ouster sent a chilling message: DARPA could innovate, but not in ways that reshaped America’s industrial trajectory. This shift reflected the ascendant neoliberal belief that government should avoid “picking winners and losers,” effectively barring DARPA from pursuing the ecosystem-shaping projects that had once engendered new industries.

Through the 1990s this constraint deepened, narrowing DARPA’s freedom to explore politically sensitive or industrially disruptive technologies. When the Total Information Awareness counterterrorism research program emerged in the early 2000s, the political backlash reinforced the limits already imposed. DARPA had managed TIA’s research office and funded advanced prototype data-analysis tools, but it never operated surveillance systems or ingested real personal data. Yet the controversy made clear that crossing political boundaries now carried institutional consequences. By the mid-2000s, DARPA was no longer permitted to act as an engine for national-scale technological advancement.

Industrial Decline

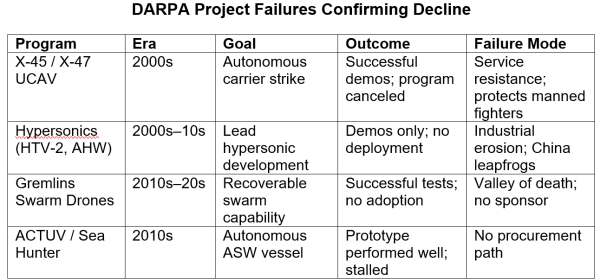

The collapse of America’s diversified industrial base and the consolidation of its defense contractors fundamentally altered what DARPA could accomplish. In the 1970s and 1980s, DARPA could hand a radically unconventional design to a firm like Northrop, Lockheed, or Hughes and expect rapid iteration by engineers empowered to take risks. Today, five mega-primes dominate the landscape; their financial models reward predictability, long contract cycles, and incremental improvements to legacy platforms. A revolutionary DARPA prototype now threatens, rather than complements, the revenue streams of the remaining mega-primes. As a result, many DARPA breakthroughs die not from technical failure but from a lack of industrial appetite to develop them into fielded systems. This is the second structural failure.

Perverse Incentives

DARPA can still generate astonishing prototypes, but the modern defense acquisition system no longer provides a pathway to transition them into actual capabilities. Programs that produce successful demonstrations—such as autonomous carrier aviation, hypersonic gliders, or autonomous surface vessels—often stall because procurement requires inter-service consensus, stable multi‑year funding, and the willingness to disrupt existing doctrine. The system now rewards starting programs, not finishing them; extending timelines, not fielding capabilities; and commissioning studies instead of building forces. This is the third and final structural failure: the emergence of a perverse incentive regime under which success is dangerous and failure is profitable.

The Valley of Death

Defense analysts refer to the treacherous gap between a successful prototype and a fully funded military program as the “valley of death.” In theory, DARPA hands off promising technologies to the services for adoption. In practice, the handoff has become nearly impossible. Modern acquisition rules require multi‑year budgeting, rigid requirements processes, and the alignment of service doctrine—all of which strongly favor established platforms over disruptive new capabilities. As a result, in recent years DARPA projects that demonstrate clear technical success often stall when no service is willing to sponsor procurement or restructure existing force plans. The valley of death has grown to the extent that it now functions as a structural barrier: a place where groundbreaking work is celebrated, briefed, and studied, then quietly set aside.

Case Study: The UCAVs That Worked

DARPA’s X-47 Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle program demonstrated that a stealthy, autonomous strike aircraft could operate from a carrier deck; execute coordinated missions; and, in contested environments, perform roles traditionally reserved for manned aircraft. Despite these impressive technical successes, the program died the moment it reached the transition point requiring service sponsorship. The Navy reframed the mission to emphasize surveillance over strike, protecting the budgets and institutional primacy of manned tactical aviation. With no service willing to champion procurement, the project fell into the valley of death. The parallel X-45 program for the Air Force, which had also demonstrated successful autonomous strike operations, met the same fate for similar reasons. Russia and China are both moving toward operational deployment of high-performance, stealthy UCAVs such as S-70 Okhotnik and GJ-11 Sharp Sword — precisely the category the U.S. pioneered with the X-45 and X-47 programs before canceling them.

X-47 UCAV – rejected by naval aviators

Russian Sukhoi S-70 Okhotnik UCAV – Note resemblance to X-47

Conclusion

DARPA’s decline is not the result of internal failure; it is the consequence of a deteriorating national defense ecosystem. In the era of ARPANET, the United States possessed the political confidence, industrial depth, and bureaucratic flexibility to absorb and exploit DARPA’s boldest ideas. Today, DARPA still dreams big, but those dreams now collide with political caution, industrial risk aversion, and perverse incentives that punish success and reward stagnation. DARPA’s innovative imagination remains intact. What has faltered is the country around it, which no longer possesses the institutional ability to turn breakthrough ideas into national capabilities.

might just as well forward the blueprints: ‘to whom it may concern’

In the long run not such a bad idea

Not mentioned here is that DARPA funded, at MIT and elsewhere, many of the software language and technology innovations that fuel today’s world. The pattern was:

– Report on what you did last year.

– Fantastic! We’ll fund you for another year.

– Report on what you did…. repeat….

Note that there was no demand to pre-determine what the research would accomplish—a very enlightened approach.

It would be interesting to compare this approach to how China recently has been funding and encouraging research in strategic areas.

‘The Dream Machine’, Mitchell Waldrop, is an excellent description of the ARPA people, the approach and its effects. Alan Kay, inventor of Smalltalk and researcher at the Xerox PARC that inspired the original Mac development team, says “The best book about the ARPA/Parc research community (Parc sprouted from ARPA) is “The Dream Machine” by Mitchell Waldrop: it is both the most complete and most accurate.”

Very informative, thanks. I just have a couple of questions about terminology.

“DARPA had managed TIA’s research office” What is TIA?

Under the Industrial Decline header, in context, what is a mega-prime?

TIA == Total Information Awareness

Mega-Prime – just a way of noting the tremendous consolidation of many diverse defense industry companies into just 5 big ones. Meaning a lot less competition, and a consequent drive to take less risks and milk profits by taking a short term profit maximizing approach to running their businesses.

Total Information Awareness

The “prime” is the company that leads a project. They may subcontract bits to other companies. A “mega prime” is one of today’s bloated monstrosities whose only goal is shareholder value.

TIA was Total Information Awareness, a program conceived at the height of War on Terror paranoia. It was meant to create a comprehensive tracking system for the U.S. population that would permit detection of terrorist planning or activity. The blowback from civil liberties and public interest groups was immediate and powerful, and DARPA felt the heat.

Mega-primes are the huge defense industry corporations that emerged from a series of mergers. They are Boeing, Lockheed-Martin, Northrup-Grumman, General Dynamics, and RTX (formerly Raytheon).

HH: It was meant to create a comprehensive tracking system for the U.S. population that would permit detection of terrorist planning or activity.

It was more complicated than that. I talked with many of TIA’s principals up to the level of Robert Popp, Poindexter’s second-in-command, though not to Poindexter himself.

HH: ‘The blowback from civil liberties and public interest groups was immediate and powerful, and DARPA felt the heat.’

That ‘blowback’ was instigated by the US intel agencies and security establishment deliberately leaking what TIA was doing to move the surveillance programs which TIA had created to NSA and CIA, etc., where they could be used without the restraint of anonymizing the US population’s data that TIA would have operated under — and indeed without any restraints except those the intel agencies and security establishment placed on them.

https://www.technologyreview.com/2006/04/26/229286/the-total-information-awareness-project-lives-on/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Data_anonymization

For further deniability, some of those surveillance programs were additionally farmed out via the CIA-founded venture capital firm In-Q-Tel to the likes of private contractor Palantir, created and funded in 2004 by In-Q-Tel for that purpose.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/In-Q-Tel

HH: (TIA) was ….a program conceived at the height of War on Terror paranoia … to create a comprehensive tracking system for the U.S. population that would permit detection of terrorist planning or activity.

No. TIA began in 1998 before 9-11 and the ‘War on Terror’ with a cluster of DARPA-funded programs at MIT for biodefense purposes.

Essentially, after the Soviet Union’s fall, from 1991-92 on, Washington and the security establishment at places like Sandia Labs became increasingly freaked out by learning about the achievements of Biopreparat, the Soviet program bioweaponeering project which employed approx. 40,000 technical personnel and ran for three decades–

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biopreparat

It was realized that (1) with rapidly advancing technology, what Biopreparat had done and much more was increasingly achievable by far fewer personnel with far smaller capitalization and footprint; and (2) the US had absolutely no defense against such things and the only way to detect they were happening was when segments of the US population began falling ill and/or dying.

In other words, the canary in the coal mine would be the U.S. population. Hence, data surveillance programs to identify patterns suggesting pathogen release by surveilling Americans’ health records, etcetera, all of which were even more widely distributed across any number of places with less availability than they are now.

Those MIT biodefense programs that began in 1998 then received further funding after the anthrax attacks of 2001 —

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2001_anthrax_attacks

–and were expanded under the name of TIA.

So here’s the founder of Palantir discussing how he views that whole competitors/innovation/free market stuff:

Peter Thiel on why competition is for losers

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z3D8Vo9hRyw

Here’s the same guy pissing and moaning that innovation has stalled:

Peter Thiel: Why Scientific Progress is Stalling Out

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KtUEBIibH64

Wokeness, safteryism, a bunch of the other PolID tar babies are tossed out there.

China seems to be doing just fine with government support of key industries and education, thriving free markets where companies fail, and real competition and innovation occurs. America use to do that too, but neoliberalism, bailing out Wall St losers, bailing out Silicon Valley losers, endless tax cuts for billionaires, etc, ended all that.

And he will NEVER see this. Got rich young, and is determined that he gets no real competition and endless government support. All the Silly Con Valley tech lords think like this.

You mean national-level industrial policies? Japan also did an excellent job with them back in the day, and books like Japan as Number One were once ubiquitous in American bookstores.

Yes, I don’t doubt that there is a history of what can be called industrial policy in other countries too. It has a place in American history going back to Alexander Hamilton:

Report on Manufactures

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Report_on_Manufactures

There was a time when “industrial policy” was a derogatory term representing stupidity, rigidity, and selfishness.

I suppose the fatal flaw here is that DARPA was designed to deliver disruptive technologies. Only trouble is that in sclerotic industries and militaries, disruptive anything is the last thing that they want. You can’t have all those rice bowls being knocked over just because it will give a competitive edge to the US. Predictability is the only thing that really matters.

The real money in the MICIMATT is in production! F-117 was a research project with 70 odd test models. F-35 is a massive, long term career! As with many developmental research projects many never go to profitable systems. War story when F-117 was starting out it was deployed to a remote air base near Las Vegas, the regular USAF maintenance airmen took a B737 to work it was secret they could not talk about the aircraft! I knew a airman who did this, after he could talk about it.

I agree. DARPA has done a lot of good projects supporting basic research, and innovation in mission applications.

UCAV may have been killed by the “piiot union” demanding manned aircraft when the aggressive pursuit of remote navigation and control technology is almost 40 years old. In the USAF in particular pilots’ wings equate to “universal management badge” potential for general ranks.

In the late 1990’s I saw DARPA efforts to improve IT applied to operational command centers. Many innovative network and data exploitation techniques that the services would not bother funding.

Back in those days I worked for a company making bleeding edge visible light sensors. For a product demo a colleague and I had to visit that unnamed base out in the desert. After receiving our special credentials for the visit we spent the night in Los Vegas. The next morning we had to be at a special terminal at the airport at zero dark thirty where we boarded the unmarked B737 for the relatively short flight to the base. Nobody spoke during the flight. Upon deplaning we had to walk down the stairs single file and present our credentials to unsmiling, cammo uniformed and heavily armed military personnel. One memory was of an unmanned sandbagged machine gun emplacement near the tarmac that had a large number of bullet casings scattered all around the front of it. Also, that I needed a guy to accompany me when I went to the bathroom. We were both glad when that demo was over.

DARPA was created to counter the Soviet Union. Now that the Soviet Union has collapsed and there is no clear threat to the United States, DARPA is no longer necessary. Although some Americans claim that China or Russia poses a threat, they don’t genuinely believe that America’s technological superiority is in jeopardy. Meanwhile, China and Russia are innovating every day to counter American military and economic threats.

One important issue the article overlooks is why DARPA, as an institution, excelled before the 1990s but appears not to have done so since.

What changed, and why?

What global shifts removed the incentive structure that were there prior to the 1990s but were absent after the 1990s for DARPA to perform at its earlier level of excellence?

My conjecture is that the collapse of the USSR in the early 1990s removed the sense of existential threat felt by Western states, and especially by the United States.

During the Cold War, this existential threat was the primary driver in my opinion to DARPA’s outstanding performance and that of many similar institutions in the USA, because their work was perceived as a matter of national survival.

With that threat gone with the fall of the Soviet Union, the central motivating force that had pushed these institutions toward extraordinary achievement weakened, and that resulted in what we witness today, many once-brilliant American institutions decayed to pale shadows of what they were.

A similar pattern can be seen in the corporate world. When companies are in their startup phase and fighting for survival and market share, they are driven by an intense focus on organizational excellence and delivery. Once they achieve market dominance, however, many lose that focus and energy, gradually becoming complacent, rigid, and far less innovative.

Your comment reminds me of part of the dialogue after Richard Hamming gave his ‘You and Your Research” talk, dialogue quoted here:

The existential threat of nuclear war is undiminished, and new threats of terrorism and cyber warfare exist. As the article points out, DARPA’s failure is not internal to the organization, but attributable to the decay of the U.S. defense industrial base. There are multiple causes of this deterioration, including short-term profit incentives, risk aversion, and the normalization of legal corruption. Attributing all of this to the end of the Cold War is simplistic, especially in the context of its current revival.

Yes. Corruption, financialization, monopolization all played large roles.