This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 532 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, PayPal, Clover, or Wise. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, supporting the commentariat.

For the first time in more than 50 years, the world’s two largest nuclear powers operate without a single binding limit on the size of their arsenals. The Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) and its successor frameworks, START II and New START, were the backbone of U.S.–Russian nuclear restraint, placing ceilings on deployed warheads and creating the most robust verification system in arms-control history. As the clock runs out on New START’s final extension in February 2026, the structure that anchored global strategic stability is dissolving. Its disappearance marks not only the lapse of a treaty, but the erosion of a philosophy: that nuclear powers can manage arms competition through transparency, predictability, and law. This article describes the background and characteristics of the START treaties and the likely consequences of abandoning them.

MIRV nuclear warheads – The fewer the better

Origins and Evolution of START

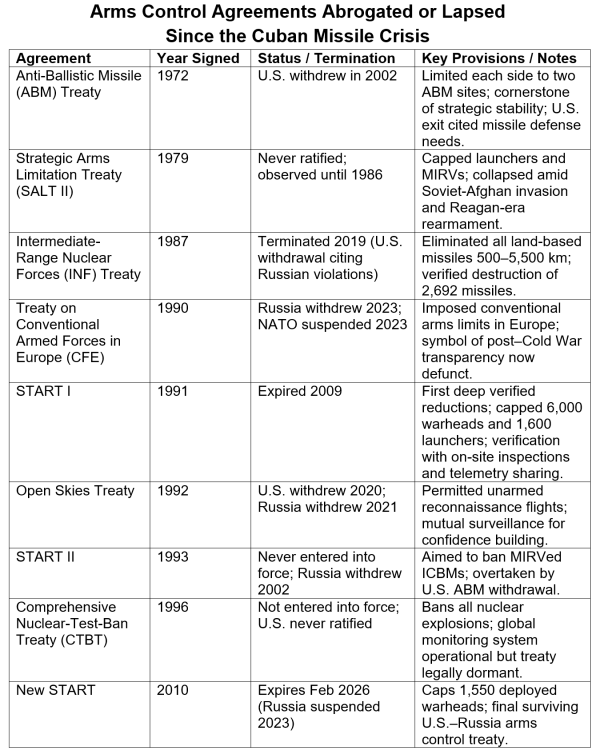

START emerged from the late Cold War recognition that an unconstrained arms race was both unaffordable and perilous. START I, signed in 1991 and entering into force in 1994, required each side to cut deployed strategic warheads to 6,000—a dramatic reduction from Cold War peaks—and introduced on-site inspections, telemetry sharing, and detailed data exchanges. A follow-on, START II (1993), sought deeper cuts and a ban on multiple-warhead land-based missiles (MIRVs) but never took effect after Russia withdrew in protest of the U.S. exit from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. The spirit of restraint revived in 2010 with New START, limiting each side to 1,550 deployed warheads on 700 launchers and modernizing verification procedures. Extended once by mutual consent in 2021, New START now stands as the last surviving U.S.–Russian arms-control accord—and it is expiring with no replacement in sight.

Why START Mattered

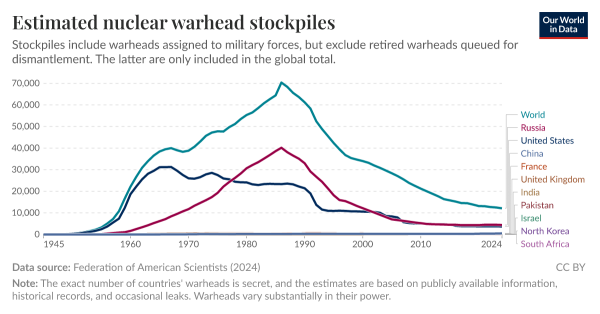

- Major reduction in warheads. Under the START treaties, the number of nuclear warheads worldwide declined substantially from over 50,000 to around 10,000.

- Predictability. By mandating regular data exchanges, START replaced speculation with facts. Each side knew the other’s arsenal size and composition, removing incentives to plan against inflated threats.

- Verification. The treaty’s inspection regime, including over 18,000 on-site visits since 1994, became the gold standard for confidence building. Inspectors verified missile serial numbers, launch-tube counts, and base inventories, confirming declared reductions.

- Crisis Stability. Quantitative ceilings narrowed the benefits of a first strike and fostered a stable deterrence balance. Leaders could calculate, not speculate, in moments of tension.

- Symbolic Power. START proved that adversaries could negotiate in good faith. Its success lent credibility to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and inspired parallel efforts such as the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. Arms control was not charity; it was strategic insurance.

The Rise and Fall of Nuclear Arms Control

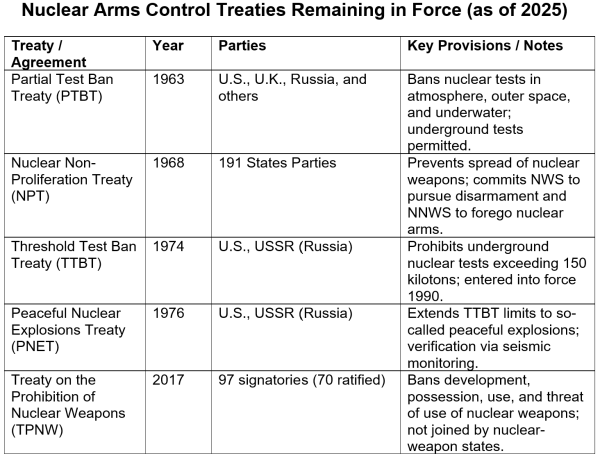

The Cuban missile crisis led to a willingness to engage in arms control diplomacy between the U.S. and the USSR. Beginning with the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1963, a series of treaties succeeded in reducing tensions among the nuclear powers and inhibiting arms racing. Only a few of these treaties are still in force.

Beginning in 2002, increasing tensions between the U.S. and Russia led to the abrogation or lapsing of the most important nuclear arms control treaties. Perverse incentives of political expediency and military aggrandizement resulted in the removal of these important safeguards against nuclear war and moved the doomsday clock closer to midnight. New START, the last of the nuclear arms reduction treaties, will lapse in February of 2026.

The unraveling of the START treaties began with deteriorating trust after 2014, when Russia’s annexation of Crimea and subsequent sanctions froze broader dialogue. COVID-19 halted on-site inspections in 2020 and they never fully resumed. In February 2023, Moscow suspended participation in New START, citing Washington’s “hostile actions” and NATO expansion. The United States accused Russia of noncompliance for refusing inspections and data updates. With war raging in Ukraine and bilateral diplomacy at its lowest ebb since the early 1980s, neither capital is preparing a successor treaty. As the 2026 deadline approaches, START is technically alive but functionally defunct. Putin recently proposed a one-year extension of New START, but there has been no reply from the Trump administration.

Consequences of New START Expiration

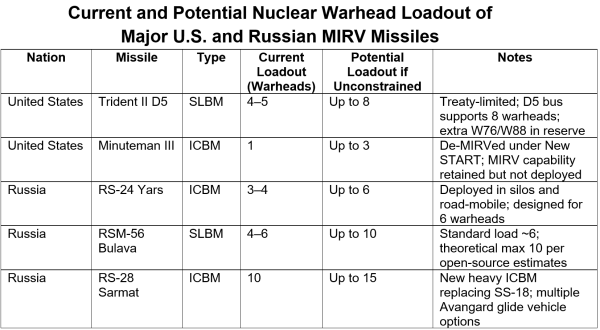

Return of the Arms Race. Without ceilings, both powers are free to expand their arsenals of deliverable warheads. The United States is modernizing every leg of its triad: the Sentinel ICBM, B-21 bomber, and Columbia-class submarines. Russia is fielding new systems such as the Sarmat heavy missile and Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle. Lacking mutual limits, planners will assume worst-case growth, inviting a costly and destabilizing buildup reminiscent of the 1960s. Both the U.S. and Russia could bring their MIRV missiles up to full deliverable warhead capacity by adding warheads from existing inventories.

Collapse of Verification. Once inspections end, intelligence estimates must fill the gap. Satellite imagery can count silos but not warheads; telemetry can be spoofed. The disappearance of verified data will force each side to hedge with excess capacity, compounding mistrust.

Crisis Instability. In a confrontation between nuclear powers, leaders will operate with greater risk. Uncertainty about force survivability may push both sides toward launch-on-warning postures, shrinking decision time and raising the odds of miscalculation.

Global Ripple Effects. Great-power restraint has underpinned the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) bargain: non-nuclear states renounce weapons in exchange for nuclear powers’ commitment to disarmament. If Washington and Moscow abandon limits, Beijing, New Delhi, Islamabad, and Pyongyang gain precedent to expand unchecked. Allies under the U.S. umbrella may question extended deterrence, spurring calls for independent capabilities.

Breakdown of Nuclear Diplomacy. Since SALT I (1972), multiple treaties have affirmed that nuclear excess is dangerous and reversible. Their collective erosion, with INF dead, Open Skies withdrawn, now START expiring, signals a new era of diplomatic nihilism, where power alone dictates numbers.

China’s Nuclear Deterrent and a Three-Body Problem

Perhaps the worst consequence of the abandonment of START would be the increased incentive for China to build up its nuclear forces. Historically, China maintained a “minimum deterrent” (~400–500 warheads, growing toward 1000 by early 2030s, per U.S. DoD estimates). Its doctrine relies on assured retaliation. START’s dissolution would alter this assumption.

If the U.S. and Russia expand beyond 1,550 deployed warheads, the gap between Chinese and other superpower arsenals widens dramatically. Credibility of China’s second-strike deterrent diminishes because U.S. and Russian counterforce capabilities would outpace China’s survivable forces. Not only would China face a growing U.S. nuclear arsenal, it would have to defend against the possibility of a combined strike by the U.S. and Russia. The possibility that each party in a nuclear deterrence triad might confront a joint attack by the other two creates an unstable “three-body problem” because each party’s effort to match the combined arsenal of the other two creates an asymmetry with each of the other two, which drives a self-perpetuating cycle of arsenal growth.

China’s DF-61 ICBM – Big trouble for arms control

Prospects for Renewal or Replacement

Reviving formal arms control faces formidable political headwinds. In Washington, Congress remains wary of treaties amid partisan divides. Moscow, under sanctions and wartime censorship, views strategic arms negotiations as a concession. Still, narrow confidence-building measures are conceivable: limited data-transparency accords, mutual test notifications, and moratoria on new deployment categories (e.g., space-based weapons). Longer term, stability will require tripartite engagement with China, whose arsenal complicates bilateral ceilings. Yet Beijing rejects verification parity until its forces near U.S.–Russian levels. In the absence of a grand treaty, policymakers may settle for informal norms and reciprocal statements, a fragile substitute for legally binding limits.

Conclusion

START’s expiration is more than another lapsed treaty; it is the removal of the last barrier separating structured deterrence from unconstrained rivalry. Without the START verification mechanism, conservative assumptions will rule and a nuclear arms race will resume, leading to growing defense budgets, hair-trigger alerts, and crises threatening catastrophe. Restoring arms control treaties, even at a modest level, is an urgent priority. Transparency is cheaper than rearmament, and treaties, however imperfect, are more reliable than notional deterrence. It is critically important for the safety of mankind that the New START treaty be renewed, and that further arms control agreements be implemented. It took decades to build nuclear trust. Letting START lapse could usher in a perilous new era of nuclear terror.

Will it really? Depends on what Russia does largely.

Let’s question the conventional wisdom on this topic a bit. Which is that arms reduction is a good thing. But is that really the case empirically?

Did the US ever attack Russia directly when both had 30,000 nukes pointed at each other? No, it didn’t.

Is it doing it now after arms control treaties have reduced the arsenals by an order of magnitude? Well, US weapons operated by US military have been killing Russians on Russian territory for three years now. And the Tomahawks are on the way.

Does that objective empirical fact support the conventional wisdom that arms control is a good thing? It kind of doesn’t, does it?

Because what is happening is that when both sides have 30,000 nukes, it is much more difficult to imagine neutralizing them with a first strike sufficiently much to blunt the second strike to an “acceptable” level than it is when there are only 1,500 deployed. If you take out 90% of 1500, there are 150 left, and you lose some cities, but not the whole country, if you take out 90% (and it will in fact be a lower percentage) of 15,000, there are still 1,500 left and you do lose the whole country.

So, seemingly paradoxically, the fewer the nukes, the more unstable the situation is.

Then there is the argument about spending. That also doesn’t quite work the way conventional wisdom has it, which is that these programs are a giant giveaway to the MIC. In the USA they are — trillions will be shoveled towards Boeing, Raytheon and Lockheed Martin, and now new players like Musk and friends too, and a large portion of that will be pocketed.

But in Russia the MIC is state owned so it works very differently. It took the grand s**t show of the SMO for me to understand this, but now it is quite clear — Putin has been begging for arms control not because he is so much worried about nuclear war as he is about the spending. But he is not worried about the spending because it would hurt Russia as a country, no. What happened when Gorbachev gave away everything was that in effect the 25% of GDP that was going into the military was slashed to 5% and the difference was pocketed by the emerging oligarchy, who then proceeded to move half of it out of the country and the other half they converted into mansions, limousines and megayachts.

In the process the country was deindustrialized dramatically, with core competences in key areas lost (watch how hard it has been to re-learn how to build large planes). Because much of the advanced Soviet industry was closely tied to the military, and once the arms race ended, there was no need for it.

Strategic remilitarization would have the inverse effect. It would necessitate further reindustrialization and onshoring of critical high-tech sectors, which will be largely under state control. And that will be a good thing, because advanced technologies will have to be developed. And some of the resource that went towards the oligarchs will have to go towards the remilitarization effort. Because there isn’t really anywhere else to take it from — the general population has been squeezed too much by four decades of Soviet collapse and religiously followed neoliberal policies. Now the oligarchs would have to be squeezed. Which would be a good thing too.

So from a Russian perspective ramping up strategic weapons again is a good thing — they have a technological lead in many delivery systems, upping the numbers will make them more secure, and it will have beneficial effects to Russian society. For the US, on the other hand, it will be a negative, by exacerbating the trends that are driving the US towards collapse.

And yet Putin is on his knees begging for arms reduction while the Americans are pushing in the other direction.

Make that make sense…

It only makes sense if Putin is working for the Russian oligarchy and not for the Russian people.

I don’t know if the last sentence (that arms limitation agreements are better for oligarchs than the people) quite makes sense unconditionally, but everything before that does make a peculiar sense.

The main reason we don’t like stockpiling arms, especially nukes, I think is that it makes us feel “icky,” or more properly, uneasy at all things that could go wrong. But, as you say, that possibility disciplines people, I wonder, makes people weigh the consequences of their actions more soberly, perhaps. It could very well be that the elimination of the likelihood of real and sudden and very messy deaths is why our leaders are clowns. If it gets us better leaders out of fear, maybe a new nuclear arms race might not be a bad thing. (As I think more about this, the more I think Karaganov was right, except I think the demonstration strike should have fallen on something like Copenhagen, not some far off uninhabited place.)

If nothing else, nuclear arms reduction is an area in which Russia can negotiate with the USA directly at a high level, without the interference of US allies. From a diplomatic point of view, the process could be fruitful, even if no agreement is reached concerning nuclear arms.

If Putin offered Trump a deal advantageous to the US, then Trump would still get stuck with the job of trying to get it ratified, exposing various contradictions among US elites.

If the USA refuses to negotiate, then Russia has an easier time developing an entente with China, and perhaps also India. Compare how Russia, France, and Britain put aside differences, in order to face their German problem, prior to the Great War. It didn’t start as an alliance, but it ended up as one.

If the USA demands that PRC take part, owing to the latter’s nuclear force expansion, then that would result in an ad hoc multipolar forum which, again, could be of diplomatic value beyond nuclear arms control.

Instead of renewing START, Potus decides that pushups and rope climbing will protect the U.S. from nuclear disaster. His thought process, such as it is, is too painful to contemplate.

For years USA have destroyed countless countries until they finally turned their attention to Russia and China.

To some extent, I blame Russia and China for not doing more to support the nations the USA was invading.

Take Libya, for example: Russia even voted in favor of the no-fly zone, only to later admit the USA abused it. What a joke!

They clearly knew what the U.S. was planning, yet they went along with it perhaps hoping to do the U.S. a favor .

Using GM’s standard of empirical evidence, one may conclude that Russian roulette is a safe activity if the revolver hasn’t fired after several spins of the cylinder. Those familiar with the history of the nuclear arms race are aware of multiple incidents in which the world came very close to nuclear war. The assertion that more nuclear weapons will make us safer is absurd.

The keystone was the ABM Treaty.

When the USA decided to abandon the assured-destruction/second-strike type of nuclear regime, everything else in the realm of strategic arms limitation began to unravel.

The decision to commit to deployable missile defense was made by the younger Bush, and has become fixed US policy ever since, with a deep bipartisan consensus.

I find it strange that an article about nuclear arms control barely mentions missile defense, even though that is the central issue.

Missile defense is not about passive protection. It’s about enabling first strike.

First strike has always been the main problem. It was usually estimated that the side attacking first would destroy about 80% of the opponent’s force before they could strike back. That meant 20% of your force had to still be strong enough to deter the enemy.

Then, once misses, malfunctions, the share of the force down for maintenance at any given time, disruption of command, etc. are all taken into account, it’s more like 5% of your force still has to be strong enough to deter the enemy.

If you ever wondered why Cold War nuclear arsenals seemed so absurdly oversized, it was because the respective high commands were insuring against an anticipated 95% loss of effectiveness in the event of war. Hence the term, assured destruction. Surpise attack? Murphy’s Law? No matter. The story is over. We all get nuked.

With this in mind, one can understand why strategic missile defense is so destabilizing. The defense doesn’t have to be much good, to start having a big impact on the deterrent value of retaliation. A defense that could counter merely 3 or 4 percent of an opponent’s total force could perhaps be good enough to make first strike thinkable once more, to anybody ambitious enough and ruthless enough to want to rule the world.

Moreover, when second-strike meant assured-destruction, the superpowers could avoid the more dangerous readiness postures such as “launch-on-warning” or “delegated launch authority” or worse, “launch-by-default.” Instead, aside from periods of high crisis, both superpowers mostly maintained a de facto policy of “await, then retaliate.”

MAD actually limited the madness, which was why the war nuts hated it more than did the peaceniks. With assured destruction firmly established, it became possible to first limit, then gradually reduce, nuclear arsenals, while building some trust and cooperation through practical experience. Civilization tiptoed forward.

When G.W. Bush, Barack Obama, and their successors chose to pursue their policies of “no peer competitor” and “indispensable nation,” they chose to repudiate the civilized bounds of deterrence, and revert to old-fashioned machtpolitik. After all, if somebody else can deter you, then you’re not indispensable, and they can compete with you if they want.

Missile defense is meant to enable a first strike capability. First strike capability enables escalation dominance. Escalation dominance makes for hegemony.

This has been a long way of saying that US political leaders have become contemptuous of arms control, because they think they can rule the world, and if it comes to a world war, they think they can win, at a cost they can accept.

Of course, humanity has seen this movie a few times already. History resembles a Hollywood franchise, with the same plot over and over, and with bigger budgets and bigger explosions in each sequel. But the monsters we fear never go away, so we have to kill them again and again.

Accurate points, but let’s then, in that context, remember that the US walked out of the ABM treat in 2001, yet the Kremlin still signed New START in 2010.

And ABM defenses plus small arsenals is much more destabilizing and risky than ABM defenses plus large arsenal. As you yourself described very well.

Then 15 years later we have the US about to launch Tomahawks into Russia. And yes, I know there are no properly working ABM defenses, but maybe they think Aegis installations in Europe and ships in the north Atlantic and arctice can take out enough missiles? Who knows…