Yves here. I hope readers in Europe and the UK and those otherwise knowledgeable about EU politics and governance will pipe up about this piece. At a bare minimum, it’s a good critical thinking exercise, but members of our commentariat can hopefully provide additional insight into regional political and economic dynamics that feed Euroskepticism.

This article makes a bold claim, that Euroskepticism actually leads to (or at least correlates with) lower growth. Its authors contend that the causality runs in the direction opposite of the one described by most economists and analysts: that economic stagnation produces “throw the bums out” voter responses, which in many cases means Euroskepticism.

Some reactions from a non-European, so take this with ample salt.

First, in opposing the conventional “falling behind economically leads to anti-establishment voting” the authors seem to be going in an “either-or” direction. I suspect that there is much more likely to be a very complex interaction. If an area of a country falls behind, some of those who can, mainly the young, will leave. So those who remain will be older and more conservative. Investors do tend to prefer areas with more demographic growth and younger workers because cheaper. This dynamic would appear to be important and I would contend more important than voting preferences.

Second, sometimes choosing to be retrograde pays off over the longer term. Portland, Maine, turned down the opportunity to become a major Ford site, IIRC in the 1930s. The arguably small-minded town fathers wanted to keep their culture. So Maine remained largely rural and poor. But it’s not hard to argue that Portland is now better situated that auto industry darling Detroit, once the wealthiest city in the US that has taken a huge fall.

Third, I wonder about their classification of Euroskeptic. The post specifically mentions Greece’s Syriza as an example. The party has likely changed its messaging, but I recall well when it took power. It campaigned on not being an establishment player and therefore uniquely able to break with existing alliances and negotiate a better bailout package than incumbents could. This may seem to be a distinction without a difference to some readers, but it was the IMF, not the EU, than devised and ran the “programs”: recall that includes lots of non-EU nations, such as Russia, Argentina, South Korea, Indonesia, Thailand, and the UK before it was part of the EU. The Bank reported in 2020 that more than half the world’s nation had asked for assistance. Yes, for Greece, the bulk of the funds actually came from EU member states, but they very much deferred to the IMF and depended on the IMF to monitor progress and devise and implement “reforms” as in austerity.

I chronicled those negotiations almost daily; there was at the time and still is a lot of misreporting of what went down. Almost no one who was Greece-sympathetic (save one MP, whose name I cannot recall) recognized that the gig was up a mere three weeks after Syriza took power. It signed a “memorandum” to get an essential mini-bailout that committed it to a yet another IMF program, fine points to be worked out.

Even more important, neither Syriza nor Greeks in 2015 were anti the EU. They were anti the IMF. From a July 2015 post (this was after the Alex Tsipras stunt of a referendum on a bailout package that had expired):

Yet quite a few pundits who claim they support self-determination for Greece advocate a Grexit despite the clear preference of Syriza leadership and the Greek public otherwise. A Bloomberg poll last week found that 81% wanted to Greece to remain in the Eurozone. That demonstrates that Greek citizens appreciate that as bad as things are under austerity, a Grexit could tip Greece into being a failed state. What is starting to happen now, the inability of companies to import, constrained access to international payment systems like debit and credit card networks, is a pale shadow of what Greece would experience with a Grexit.

Now to the main event.

By Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, Princesa de Asturias Chair and Professor of Economic Geography London School Of Economics And Political Science, Lewis Dijkstra, Urban and Head of the Territorial Analysis Team, Joint Research Centre European Commission, and Chiara Dorati. Originally published at VoxEU

Support for Euroskeptic parties has surged from the political fringes to encompass nearly a third of European voters. These movements promise a ‘free lunch’: prosperity through less integration and more national control. This column offers new evidence from across 1,166 European regions from 2004 to 2023 that Euroskepticism carries a significant economic cost. The more Euroskeptic regions have seen slower GDP per capita, productivity, and employment growth, particularly since the euro area crisis. Far from liberating local economies, Euroskepticism imposes measurable economic penalties on the very places embracing it, creating a vicious cycle of discontent and decline.

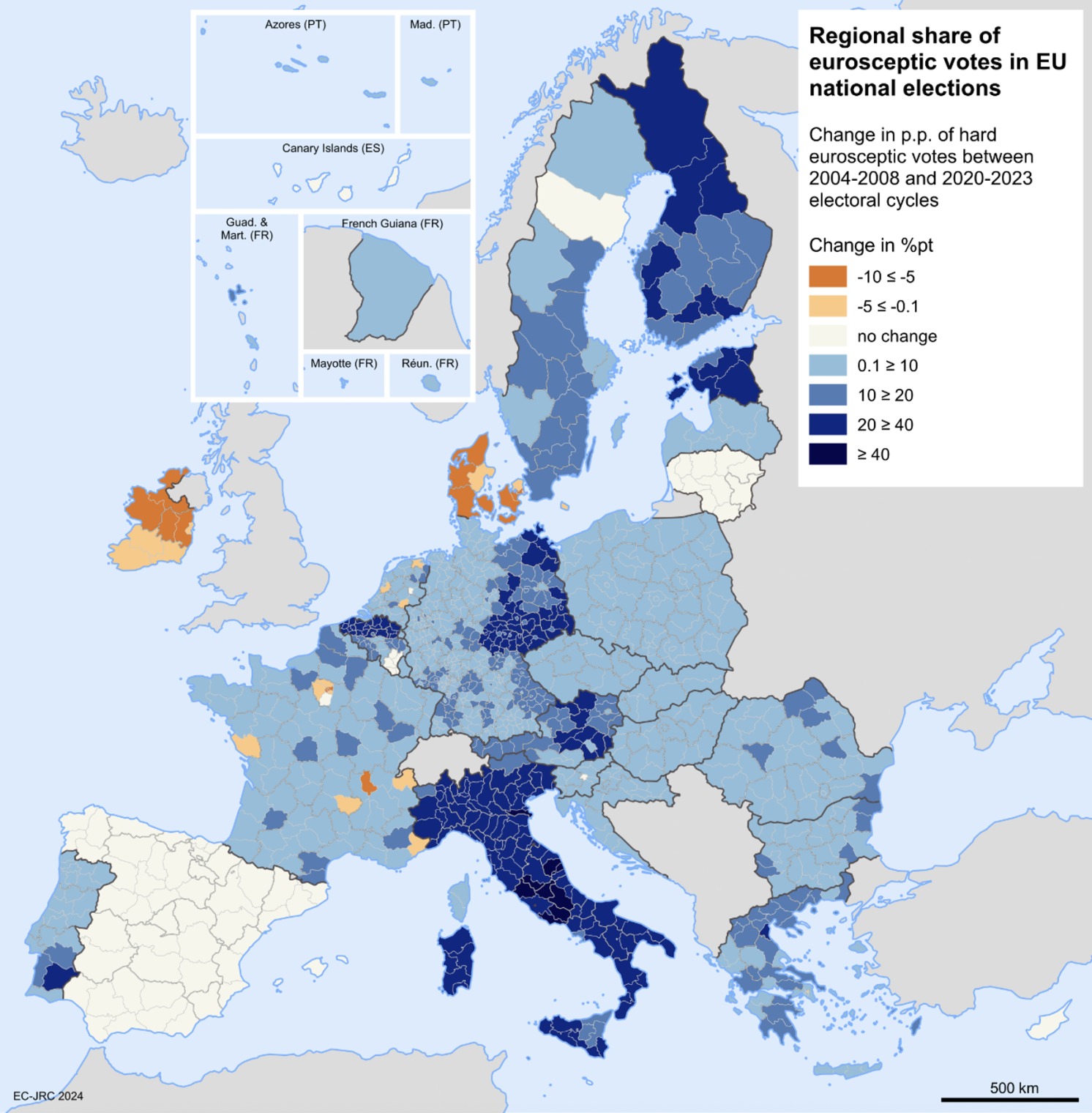

In less than two decades, Euroskepticism has moved from the margins of protest to the centre of European politics. Once confined to populist outliers – in the mid-2000s it represented a mere 3.7% of votes in national legislative elections – parties promising to ‘take back control’ now command as much as a third of the vote across EU member states. In some regions, more than half of voters now back Euroskeptic forces. The rise of such parties has reshaped electoral maps from the Po Valley to eastern Germany, from northern France to rural Sweden (Figure 1). The story being told is seductively simple: European integration has shackled prosperity. Only by reclaiming ‘sovereignty’ will prosperity be set free.

Figure 1 Change in the regional share of votes for hard Euroskeptic parties in EU national legislative elections, 2004–2008 vs 2020–2023 electoral cycles

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Our research (Rodríguez-Pose et al. 2025) examines the consequences of the rise of Euroskcepticism and challenges this assumption head-on. Drawing on regional data for all 27 EU member states between 2004 and 2023, we ask what happens to places that turn against European integration. The analysis shows that places that yield to the temptation of Euroskepticism have, over time, grown more slowly, created fewer jobs, and lost ground in productivity relative to their more Europhile peers. In other words, Euroskepticism is no free lunch and appears not merely as a symptom of economic malaise but as a contributor to it.

Going Beyond the Causes of Euroskepticism

Most economic research to date has focused on the causes of Euroskepticism, treating it as a consequence of economic distress. The argument that long-term economic pain breeds political backlash (Rodríguez-Pose 2018) has been central to understanding its rise. The geography of EU discontent closely mirrors that of long-term stagnation (Dijkstra et al. 2020). There also appears to be a strong link between external economic threats, such as the rise of import competition from China, and anti-EU voting (Stanig and Colantone 2017).

Yet this research only covers one side of the story. What happens to economies after voters embrace Euroskeptic parties, even when these parties are not in government? Can political discontent itself become an economic liability, even before Euroskeptic forces can implement policy?

There has been no previous research directly on the consequences of Euroskepticism. The closest is work on the consequences of populism, which shows that anti-system leaders worldwide typically deliver worse economic outcomes, with GDP per capita roughly 10% lower 15 years after they take office (Funke et al. 2023). According to this research, populist leaders systematically undermine performance through institutional degradation and policy mismanagement (Funke et al. 2023).

But populism is not equivalent to Euroskepticism, and most Euroskeptic parties in Europe have rarely governed. Although some, such as Fratelli d’Italia in Italy or Fidesz in Hungary, control the levers of power, many others – such as Rassemblement National in France or Alternative für Deutschland in Germany – have remained in opposition. The question thus becomes: does merely signalling widespread Euroskepticism damage regional economic prospects?

The ‘Free Lunch’ Illusion

Euroskeptic parties across the political spectrum promise renewal through liberation from Brussels. On the far right, this means national competitiveness unburdened by EU rules; on the far left, freedom from austerity and fiscal constraint. Both traditions share a belief that regaining sovereignty will translate into renewed prosperity.

Has that been the case? We draw on a comprehensive dataset covering 1,166 European regions across all EU-27 countries from 2004 to 2023. We measure Euroskeptic support using the vote shares of parties that experts classify as opposed to European integration (scoring 2.5 or below on the Chapel Hill Expert Survey’s 1–7 scale). We then track how regions with different levels of Euroskeptic voting subsequently perform on four key development indicators: GDP per capita growth, productivity growth, employment growth, and population change.

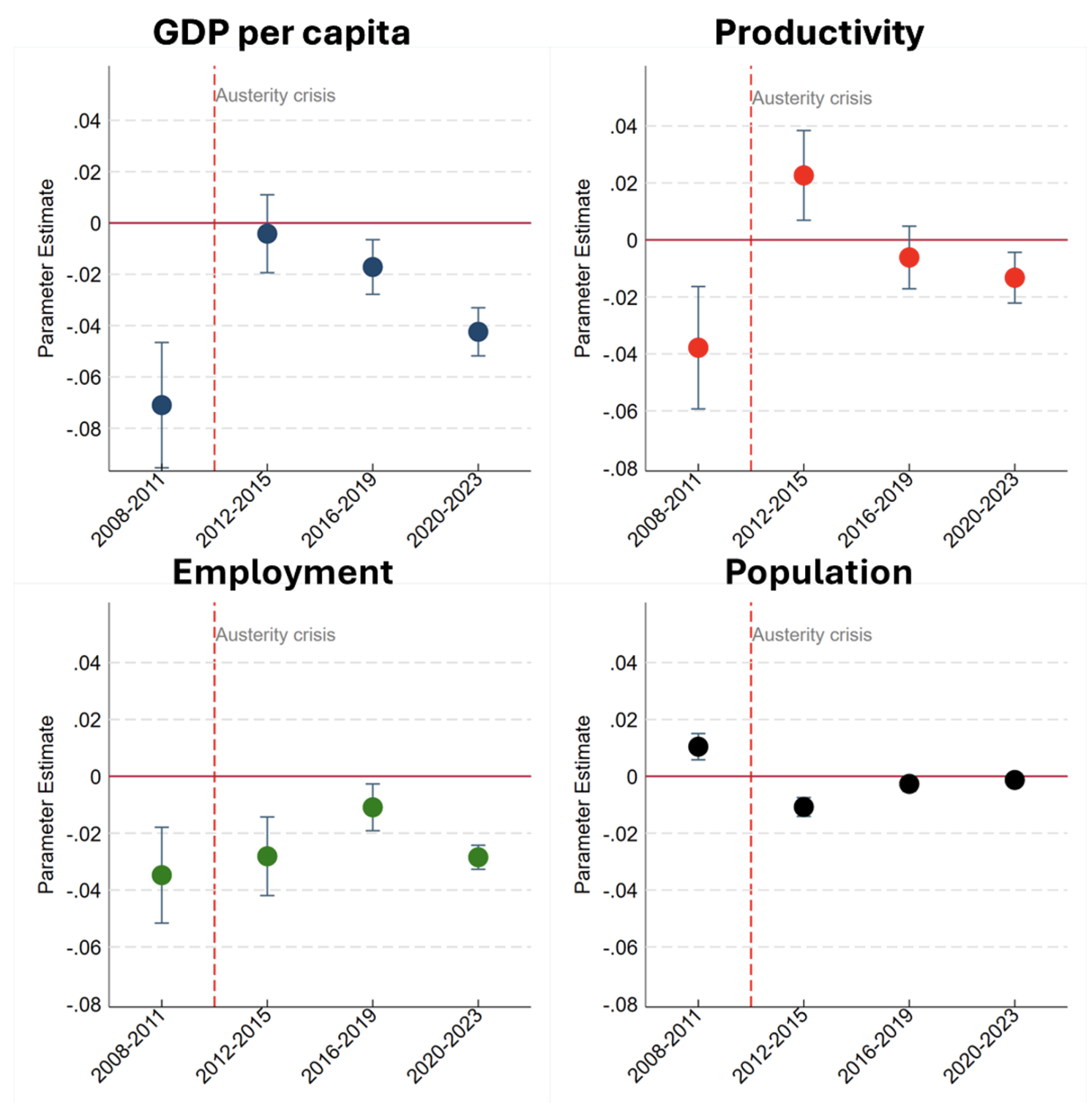

The findings reveal that a region with a 10 percentage points higher Euroskeptic vote share experiences approximately 0.35 percentage points slower annual GDP per capita growth. This may sound modest, but compounded over multiple electoral cycles, it translates into substantial divergence. Over 12 years – three electoral cycles – such a region could find itself roughly 4%–5% poorer than an otherwise similar but less Euroskeptic neighbour.

Productivity tells a similar story. Each additional 10 points of Euroskeptic support is associated with lower annual productivity growth by about 0.10–0.14 percentage points. Employment creation lags by roughly 0.25 percentage points annually, cumulating to about 3% fewer jobs over the same period. Population effects are, by contrast, more muted, although Euroskeptic regions struggle to retain or attract residents. The relationship between Euroskeptic sentiment and subsequent economic underperformance appears robust and substantial.

The Crisis as a Catalyst

The 2012–2013 euro area crisis and subsequent austerity acted as a critical juncture. Before the crisis, the economic penalty associated with Euroskepticism was present but muted. The crisis changed everything: citizens of regions with high Euroskeptic sentiment suffered disproportionately during and especially after this period.

For GDP per capita, the post-2012 penalty nearly doubled compared with the pre-crisis period. A region that is to points more Euroskeptic saw annual growth rates fall by an additional 0.16 percentage points after 2012, bringing the total effect to roughly 0.38 percentage points annually. By 2023, this translated into a cumulative income shortfall approaching 5.5% (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Development implications of Eurokceptic support and the crisis (event study analysis)

Note: The period on the horizontal axis refers to the period after the electoral cycle.

Why did the crisis amplify Euroskepticism’s economic impact? Several mechanisms likely operated simultaneously. First, regions vocally opposed to the EU may prove less effective at securing or deploying European funds. As Crescenzi et al. (2020) have shown, EU funds can mitigate rather than fuel Euroskepticism when properly deployed. But achieving this requires institutional capacity and a willingness to engage with EU mechanisms, precisely what Euroskeptic regions often lack (Rodríguez-Pose et al. 2024). Investors confronting scarce capital post-crisis may avoid regions perceived as politically unstable or potentially hostile to EU frameworks. The crisis also heightened regional polarisation. Regions with strong Euroskeptic sentiment may have experienced reduced social cohesion and institutional trust precisely when cooperation was most needed for recovery.

Not Just a Story About Attaining Power

Crucially, these effects materialise largely without Euroskeptic parties actually holding power. Despite their recent rapid rise, most such parties have remained in opposition, with notable exceptions such as Greece’s Syriza, Hungary’s prolonged Fidesz rule, or various Euroskeptic parties in Italy. The economic penalty therefore operates through channels beyond direct policy implementation.

High Euroskeptic vote shares may signal deep institutional distrust and political uncertainty to businesses and investors. When investors perceive hostility towards the EU or uncertainty about future relations with Brussels, capital flows slow, businesses hesitate to invest, and national investment and structural funds may be underused or diverted.

The political act of repudiating integration appears to carry economic penalties even before it translates into policy. Firms considering investments may hesitate when local electorates demonstrate hostility towards the EU frameworks that underpin the single market. Even without policy changes, widespread Euroskepticism can deter outside investment and raise perceived risk. The Brexit experience, where business investment stalled well before actual withdrawal, offers a vivid illustration of how political uncertainty alone can chill economic activity (van Oort et al. 2017). Uncertainty can ripple through regional economies long before Euroskeptics reach power.

Regional leaders in highly Euroskeptic areas may also adjust their agendas in response to strong anti-EU sentiment, leading to lower or different engagement in EU programmes, European cooperation initiatives, or business development strategies, even when those leaders are not from Euroskeptic parties themselves. The cumulative effect of such micro-decisions, multiplied across firms, governments, and individuals, can significantly alter growth trajectories.

A Vicious Cycle

These findings expose a troubling feedback loop. Economic stagnation and regional decline fuel Euroskeptic voting, as demonstrated by research on Europe’s ‘development trap’ (Diemer et al. 2022, Rodríguez-Pose et al. 2024). Many European regions have become trapped in persistent low growth, unable to adapt to structural economic change (Iammarino et al. 2020). As our analysis shows, Euroskeptic sentiment then becomes part of the problem, not just a symptom. Regions embracing Euroskeptic parties experience slower economic dynamism and prosperity, which likely further intensifies discontent, potentially driving even stronger Euroskeptic support in subsequent elections.

This dynamic creates a particularly pernicious form of path dependence. Voters in struggling regions turn to Euroskeptic parties seeking change and prosperity. Yet their choice – however understandable given their frustrations – appears to worsen their economic prospects, deepening the very stagnation that motivated the protest vote initially. The promised ‘free lunch’ of reduced EU integration delivering economic revival proves illusory. Instead, citizens in Euroskeptic regions effectively pay for their political discontent through foregone growth and missed opportunities.

Breaking the Cycle

The policy implications are profound. The solution is not to disparage Euroskeptic voters, whose grievances are often real, but to recognise the economic cost of channelling them through anti-European politics. Labelling the inhabitants of these regions as “deplorables”, as Hillary Clinton did in her failed 2016 presidential campaign, or treating their regions as lost causes will only reinforce alienation (Rodríguez-Pose 2018). Nor will simple fiscal transfers suffice (Borin et al. 2021). Money without engagement may soothe symptoms but not the underlying malaise. Left-behind people and left-behind places need honest political re-engagement alongside targeted economic reinvestment.

A dual strategy appears necessary. Politically, the EU and national governments must listen and respond to concerns about fairness, visibility, and local voice that drive Euroskepticism. Economically, targeted initiatives promoting regional development, education, access to capital, and economic diversification are essential. Recent EU initiatives such as the joint recovery fund and the emphasis on a ‘just transition’ in climate policy represent positive steps, but these must demonstrably target vulnerable regions to succeed.

Above all, humility is required. Many voters embraced Euroskeptic parties because mainstream politics failed them for too long. Yet their choice seemingly worsened their economic prospects; an irony that should give everyone pause. The problem resides not solely with voters or institutions but in their fractured relationship. Rebuilding trust in democratic institutions, including the EU’s capacity to deliver broad-based prosperity, remains paramount.

Crucially, governance and institutional quality matter. Improvements in regional institutions are often more decisive for growth than physical capital alone (Rodríguez-Pose and Ketterer 2019). Where local governments are transparent, accountable, and effective, EU funds translate into genuine development; where they are not, cynicism festers. The vicious cycle of discontent can only be broken by a virtuous one of competence.

Conclusion

Euroskepticism is no free lunch. Its rise exacts an economic toll that disproportionately affects those who expected to benefit from it. Europe’s future depends on ensuring that Euroskepticism does not become a permanent barrier to economic development across the continent. This requires more than platitudes about European unity or technocratic adjustments to cohesion policy. It demands responsive governance that helps transform today’s Euroskeptic strongholds into tomorrow’s success stories, reintegrating disenfranchised citizens into a more prosperous and unified Europe. The alternative – allowing the vicious cycle of discontent and decline to continue – risks fragmenting the European project from within, region by region, vote by vote.

See original post for references

A key point that the article overlooks is that there are very few political parties which have euro-scepticism as a fundamental part of their manifestos. For most, its just one of a range of policies they will emphasise according to electoral need, or as a recognition that leaving the EU is the only way they can apply their core policies (such as stopping immigration). As many parties have abandoned a hard anti-EU stance when they get close to electoral success, voters tend not to take it too seriously for the most part. This certainly applies to left and Green parties, which either changed their anti-EU stance, or just stopped talking about it once they got the chance of power. The problem fringe parties face is that leaving the EU is a much less popular policy than, say, stopping immigration, despite the reality that they are linked.

As to why this correlation exists (assuming it does, and I’m sceptical about this sort of study), then the question is why. One obvious reason could be a reduction in FDI, as much of it is directly tied to EU membership. Another possible reason is that the sceptical parties aren’t actually very good at ruling – Victor Orban, as one example, is busy doing everything he can to undermine Hungary’s natural economic advantages in favour of his particular brand of authoritarianism. His undermining of Hungary’s railway system is a case study in how not to run a country competently.

I was coming to write a similar comment. As for what i know in Spain there are no euro-sceptic parties among those which manage to get representation in the Congress. Only a few fringe parties are euro-sceptic. VOX, the “far-right” party may be less willing to let the Commission grab more and more power than other parties but this doesn’t mean it is euro-sceptic though the label is then applied to it. When euro-scepticism has been analysed at population level in Spain it is usually associated with loss of interest and distrust in politics when they are failing. In Spain euro-scepticism appears to peak amongst the younger (18-24 yr cohort) and most particularly amongst male youngsters (27% of these is “peak euro-scepticism”). These are people who distrust the EU, the state government, everything. So this is not genuine euro-scepticism but general distrust in all the institutions governing us. Unsurprisingly such distrust has to hit the EU which is seen as having a lot of responsibility, quite possibly too much responsibility, as things are going now with our deleterious EU leadership.

It amazes me that the paranoid EU sees this as kind of disenfranchising because “far right” or whatever but not because the mistakes made by the very same EU with the complicity of state governments. So, they believe this can be solved with “responsive governance” if anyone knows what the hell that means. Euro-scepticism Vigilantes?

According to the original study (by EU Commission) they used Chapel Hill Expert Survey classification for Euroscepticism.

Cursorily reading that study I believe they err in considering each vote/ecomic cycle as independent of each other. If the economical indicators go downhill for decades, and it increases resistance to, say, neoliberal policies decade after decade, their method would not see the long term trend because they are only comparing post-election economic indicators to pre-election indicators.

Then they ask if the eurosceptic vote ratio can explain the change. Well, duh!

Indeed. I saw this comment as I was writing up my take, which is:

1. neoliberalism impoverishing the periphery, between and within states

2. votes against the system increases in said periphery

3. go to 1

If you start from 2 and votes against the system are counted as eurosceptical (which they tend to be among other things) then you get votes for eurosceptical parties -> poverty.

And I end up saying essentially the same as you.

The roots of Eurosceptism lie deep in the entrails of the post-war settlement at Bretton Woods and in the way in which the European colonial regimes reluctantly decolonised, granting a form of political independence to most of their former subjects whilst maintaining control of the economic reins. If their grip were to be threatened then there was always the reminder of Patrice Lumumba and, later, the Biafran War, and on the plus side all the opportunities for the young unskilled and barely educated, as well as the skilled and educated, to make a life in the “mother country” and, in tight labour markets, to use their bodies and brains for employers who sourced overseas labour as an alternative to investing in plant and machinery at home, thus avoiding the expensive business of training enough home grown doctors and nurses, teachers and engineers, accountants and lawyers, for example, as a means to increase an organisation’s output at the lowest possible cost as opposed to effecting a real increase in productivity which offered the very real perceived danger of managers and investors being forced to deal with and operate in a high productivity/high wages economy.

Our approach to productivity was to asset strip our former colonies of trained labour and our businesses of everything that could be sold off. I observed this at first hand from the mid sixties to the late seventies as a specialist advising trades unions, and firms in difficulties, on effective ways that firms could increase their competitiveness by increasing their productivity through training, alterating the layout of production lines and re-shaping business processes, and suggesting financially feasible possibilities for improving a companies performance and the lot of the trades union members and the companies which employed me.

Of course, the concept of productivity was regarded by both government and many it not most employers as a negative tool to provide a quasi-Keynesian justification for maintaining a tight lid on wages and increasing immigration, made worse by the impact of Nixon’s decision to take the dollar off gold, so we can slot Vietnam in a a causal agent of Euroscepticism.

All six of the founding states of the EEC seemed to do reasonably well out of it but they were rising rapidly for a very low base in the immediate post-war years and their economies, including the built environent, recovered much more rapidly and effectively than did the UK’s, and that momentum continued after the Treaty of Rome.

By the time the UK joined the EU, by a parliamentary vote rather than a referendum, the pot had gone off the boil as the world struggled to adjust to floating exchange rates and West Germany became the most significant economic player in the EU because of the quality and productivity of her rebuilt and retooled production facitilties whilst the UK automatically became the most significant financial power to, I believe, the detriment of British industry. Still, the EU survived the Wilson referendum in a country weary of decline but uncertain of further change.

Neoliberalism began to raise it’s head when Callaghan formed a government in which his son-in-law, re-introduced the stunningly opaque concepts of monetarism, which took even more forms than non-Conformist Sects could even dream of, and when Jay was appointed Ambassador to Washington (shades of pre-Trumpism), he found many people who re-affirmed his doctrinal bent as he did theirs.

By the time Thatcher and Reagan got their turns, the neo-liberal ground had already been broken, and the Atlantic Alliance ended up sharing the same broad, albeit, indeteminate beliefs resulting in rapid and lasting increase in unemployment (eased latterly and fictitiously by lowpaid precarious work), house prices and asset stripping. Oh, and the stock markets danced and jigged to great heights. And this combination showed the wisdom of Confucius when he was reported to observe that, “Life is like a shit sandwich – the more bread you got, the less shit you eat”. As true today as it was millenia ago.

The EC, meanwhile, trundled on after a name change, and Margaret Thatcher’s man in Brussels drafted his proposals for a Single Market, designed to lift all national controls governing movement of people and capital in Europe, making possible for private companies form any European state to compete with state enterprises and national companies for any business going on price, given common standards throughout Europe. The, as yet incomplete, Single Market came into effect at the beginning of 1993, while the Treaty of Mastricht was very narrowly supported by a referendum in France and defeated by a referendum in Denmark in 1992. And that is the point at which Euroscepticism became a significant issue because it breached any notion we may have had about national sovereignty. A few minor changes were made to the Treaty, the tools applied, and Denmark caved. So much for national sovereignty.

The UK was not offered a referendum not least because the Government may well have suffered a humiliating defeat, as would the now pro- European Labour Party leadership.

The Tories were on a three line whip when the legislation came to the House of Commons and even those who opposed deeply were forced to vote to pass the Act – basically on the threat that if they didn’t, they would lose the Whip and the Prime Minister could go to the country with his opponents in the Parliamentary Conservative Party being unable to stand for election as Tories in their own constituencies. And that was the real jumping off point for Euroscepticism in the UK and the example soon spread to other small single issue parties throughout Europe and more than thirty years of intensive campaigning has shown that what the Enoch Powells, the Tony Benns and Nigel Farages of this world were absolutely correct when they saw that Mastricht was, to echo James Goldsmith, a ruinous trap. And we see that in the demeted activities of the tenth raters who infest, not only Brussels, but almost every government in the EU and the government of every aspiring member country.

The bases for economic failure throughout Europe lie in the past and the EU has merely exacerbated the problems. It is primarily a patronage machine which consists of ever so slightly wierd people asserting strange social, economic, political and military ideologies which twist and shift whenever it is convenient for them to do so. It is an activist organisation which acts as a hostile foreign agent operating against the citizens and subjects of member countries, paying to influence to conduct and outcome of elections, and depriving their citizens of the basic amenities – like adequate supplies of energy and cheap food – and is acting just like the federal state Enoch Powell said it would become before resigning from the Tory Party in 1974, focussing not on the struggling economies of Europe, but on holding the line for the genocidaires in Gaza, the West Bank, Syria and South Lebanon, and on keeping Ukraine from completing the Istanbul agreement and forcing its taxpayers to pony up to keep it fighting for four years so that the EU can prepare a military foolish enough to go to war against Russia. Never a good experience for Johnny Kraut. And he’ll need more than Pevitin this time around. In fact, I don’t think Russia will even let them put their boots on let alone get off the starting blocks

The EU is merely symbolic of the failure of Western governments to ensure national economies which work for every citizen in each nation and the failure of democracy to deliver competent, knowledgeable parliamentarians with some experience beyond student politics, the local council, time as a thinktank propagandist, a party function or a SPAD, who regard politics as a service to the community not as the career capable of boosting them into a well paying job in the private sector because or the weight otf their contacts list.

In short, I think that every premise on which this paper is based is false and it can only have been written by an economist who thinks that the story lies in the numbers, and not the the numbers are a a pale reflection of reality seen through a glass, darkly. In other words, it’s the usual bloody proagadist nonsense based on some strange medieval formulation of economic and political life in a world which exists only in a few minds incapable of even the most tangential grip of human and institutional reality.

Please forgive any typos. All done in a bit of a rush.

Thank you for this well written comment.

Sorry, for Italy, which is pulsating big and blue in the map above, Euroskepticism hasn’t been tried. The Lega Nord tried for some time, but the Lega has had trouble attracting votes outside its base regions of Lombardy and Veneto — and Matteo Salvini and his pal, General Vannacci, are in the Ted Cruz realm of credibility. Fratelli d’Italia was Euroskeptic in opposition but hasn’t opposed much from Brussels now that it is in power.

Further, the Italians have real grievances related to a simple fact: The EU and the euro are neoliberal experiments that are based on lowering “labor costs,” limiting individual countries’ fiscal maneuverability, and allowing free movement of capital (more or less without consequences). Italian salaries have been stagnant in real terms for more than thirty years — so the map catches the upswing in voting in Italy against going to the poorhouse.

The article truly doesn’t make clear what policy choices from the EU would be causing the discontent. I see an author named Chiara Dorati. She can’t figure it out?

Further, officially, Italy is a “team player” in the EU. I’m thinking of Mario Monti, parachuted in as a technocrat president of council of ministers. Mario Draghi, the drone of the Euro beehive, also parachuted into the government. Now he mainly drones on about competitiveness (lowering wages) and such.

This article just scratches the surface of the (considerable) impatience with the EU in Italy. And the latest antics from Pina Picierno, Ursula “Mommy Warbudget” von der Leyen, the paralysis on Ukraine and the genocide in Israel, and the absurdity of the current energy “decoupling” — aided by bombing the hell out of Nord Stream — only adds to Italian impatience.

I met a former student of Varoufakis’ in Greece earlier this year. She was a very hardcore leftist and didn’t think much of Varoufakis’ politics, claiming he was just another capitalist. Anecdotal to be sure, but it does show that the some Marxists at least don’t consider Syriza to be euroskeptic either, even though the author of this piece does.

Also, the article implies that a drop in GDP is a bad thing. I’m not so sure that’s the case.

I think she is right did you read what he said after Syria fall? He made a article that the left should stay out of Syria and not defend assad, you won’t hear him say one word about Syria anymore and that was the first time i even heard him say anything about Syria. After reading the article its no wonder he kept quiet for years about Syria war, he was on the wrong side but didn’t want to get call out by the left. The guy is a plant.

Sorry if this is a bit off…

I would cautiously argue Varoufakis is honest and it´s possibly more the issue of him being anarchist as unaccounted power and hierarchy are concerned.

Anarchist Ukrainians who seriously argued Putin needs to be fought and thus joined the AFU despite all that contradicting anarchosyndicalism, and Varoufakis are of the same ilk.

It shows you that political theory takes you only so far if you really use it like a stiff pattern and you lose touch to what is happening on the ground or because you never had any touch.

Does Varoufakis know Russia? Know military issues? No! But so does almost no VIP international leftist who made a name for him or herself since Seattle 1999. Which is the core reason why there is no viable peace movement any more in Europe.

In fact the term “peace” utters them to ignore military expertise by decree. And with that the entire “Root causes” escape them. Same with Syria.

Actually Varoufakis is a very good example why for leftists the Ukraine War was a moment of historic unraveling and an unmitigated intellectual disaster and failure.

So I really doubt him being planted in any way. It´s just how he thinks. Which makes him a real problem if he is unwilling to compromise where compromise or a different political approach would be helpful.

With Gaza he can be of use. With such more complex matters as Syria or Russia, not at all. (So your acquaintance was obviously better equipped than V.)

I read his notes which he made secretly during the not-bailout negotiations over Greece with the EU and the infamous exchange with German Finance attack dog Minister Schäuble. The double standard and utter violence applied by the EU indeed was insane.

In fact the sheer brutality of the Merkel clique was a precursor of what you now see on EU-level by the VdL administration and the authoritarian turn all over on this big big scandalous scale.

And Varoufakis on his own was willing to face and fight that behemoth. Eventually he was abandoned. But that proves he has guts.

None of this came out of the blue. Including Varoufakis´s political misconceptions in some specific areas. But that´s not just him. The entire traditional US left fails when it comes to contradictory cases such as Assad or Putin. Too contradictory for their model of thinking.

I was struggling for a few years for this very reason myself as I was affiliated to that tradition. I had to understand that one has to transform and reconsider important questions on normative issues and really educate oneself more if one intends to engage in the new era in some form.

But all that shouldn´t make Varoufakis a bad guy.

He may be vain but when he had the chance to stay in power he rejected it. And as I said – if Varoufakis failed us in certain fights so did the entire post-Marxist Left. Above all the one that has acquired an extensive academic foundation and operated in that realm.

To add to the above, I’m sceptical that you can identify something called “Euroskepticism” (spelling?) at all, let alone to a percentage point. People in Europe are fed up with Brussels for all sorts of converging and diverging reasons (largely justified, it need to be said) but this doesn’t necessarily translate into support for individual political parties. In addition, I suspect there may be a simple logical error in the argument. Regions, and even countries, that have done badly out of the EU, or see themselves as having done so, are generally in a bad way economically. But unless something unexpected happens, they will continue to be in a bad way economically in the future, and would be even if they underwent a damascene conversion instantly. Neglected regions will continue to be neglected regions. In other words, and in spite of the authors’ assertions, cause and effect are working as they normally do.

This was precisely my reaction. The places are neglected, and the EU is content to go right on neglecting them. Why shouldn’t the people remain “skeptical?”

It is not clear what they are comparing to find a correlation. My comments assume it is the change in economic indicators with the change in euroscepticism in each electoral period?

(1) if you look at the charts for the period prior to the pandemic, all the negative effects relate to the first electoral period, of the global financial crisis. If you removed this period, GDP and productivity would be a lot better and population more or less unchanged. Employment exhibits a scarring from this period but the trend is to recovery. Then the pandemic comes along and side-swipres everything again. Their economic findings look very sensitive to the period of the analysis at first sight, not at all robust.

(2) even if their finding is true, it is narrower than they claim. It is that EUroscepticism *within* the EU results in poorer growth. Is this a result of punishment by Brussels / national government? Or of misdirected regional development spending? These are just as plausible mechanisms as surly peasants lack European values so the nice jobs go elsewhere….

(3) the results fly in the face of facts. For example, the most Eurosceptic parts of Italy are the richest (Veneto, Lombardy, The Chocolate Region) . Even if these areas exhibit the same trend, they are starting from a very high base of productivity and GDP and belie the hypothesis.

Indeed, if the study included non-EU members, we would find that Euroscepticism correlates with excellent economic trends (Switzerland, Norway, Iceland).

As a thought experiment, imagine this analysis was done not on Euroscepticism but on NATO support. WIth the fake tax-haven GDP of Ireland belonging to the anti-NATO front plus a lot of Italy and previously Sweden and Finland, it is obvious that supporting NATO is bad for your economy. Butter, not guns!

The author is Chair of Princesa de Asturias in LSE supported by the Cañada Blanch Foundation and CaixaBank which recently signed agreements with the EU (750 million €) to finance small and medium-sized enterprises and the self-employed. Why the conclusions of his study are not surprising me?

This is ad homimen and a violation of our written site Policies. You need to rebut his argument and not make a logically/rhetorically invalid personal attack.

If the last sentence were omitted, would it still be ad hominem?

So if I understand, the solution to wash the euro skepticism out of the brains of the Europeans is to appear to be humble, as opposed to accountability. Sure, a just green energy transition (Hah, Germany is burning coal because of EU decisions) is going to counter the EU sending hundreds of billions to Ukraine, while cutting basic services to Europeans, with most decisions made by unelected (but apparently bribable) apparatchiks.

Most of the Euroskeptic parties with electoral clout are right-wing.

I cannot speak to Europe, but I do know that in the US conservative governance have under-performed economically.

Is it Euroskepticism, or is it right wing politics?

It’s inequality.