Yves here. This post usefully estimates how deep and durable the costs of war really are. The subtext is that they are more severe than commonly assumed.

By Efraim Benmelech, Harold L. Stuart Professor of Finance and Director, Guthrie Center for Real Estate Research, Kellogg School of Management by Northwestern University Northwestern University and Joao Monteiro, Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance (EIEF). Originally published at VoxEU

Wars leave deep and lasting scars on economies. Using data for 115 conflicts across 145 countries over the past 75 years, this column documents large and persistent declines in output, investment, and trade following the onset of war, with no evidence of recovery even a decade later. Government revenues collapse while spending remains stable, forcing reliance on inflationary finance and short-term debt. The findings show that the true cost of war extends far beyond the battlefield, reshaping fiscal and monetary stability for years to come.

The world is once again mobilising for war. Military budgets have surged to levels unseen since the Cold War, driven by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, renewed Middle East and East Asian tensions, and a widespread belief that peace can no longer be taken for granted. Governments are scrambling to raise defence spending while facing already-strained public finances, stubborn inflation, and rising interest rates. The fiscal and macroeconomic consequences of this new age of rearmament are likely to be profound – yet research offers surprisingly little systematic evidence on how wars affect economies.

Some recent contributions have started to fill the gap. For example, a VoxEU column by Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Vittal Vasudevan estimates that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine may cost around US$2.4 trillion and inflict permanent output losses of at least fifteen percent in the belligerent countries (Gorodnichenko and Vasudevan 2025). Another (Federle et al. 2024a) shows that major conflicts reduce GDP by over 30% within five years and generate lasting inflationary pressures (VoxEU, 2024). A related piece (Harrison 2023) details how governments financed total wars through debt, inflation, and coercive state action. These columns build on a broader academic literature documenting the heavy economic toll of conflict – from Abadie and Gardeazabal (2003) on the Basque Country, Collier (1999) on civil wars, and Cerra and Saxena (2008) on deep and persistent growth losses, to Blattman and Miguel (2010) on war’s long-run scars, Barro (1987) and Harrison (1998) on war finance, Hall and Sargent (2014, 2022) on fiscal-monetary consequences, and Federle et al. (2024b) on the international spillovers of conflict.

A New Global Dataset on the Economics of War

In our recent research (Benmelech and Monteiro 2025), we provide the first large-scale, cross-country evidence on the macroeconomic consequences of war for the belligerents. We construct a dataset covering 115 conflicts and 145 countries over the past 75 years, including both interstate wars (state versus state) and intrastate wars (state versus non-state).

We use a stacked event-study design: for each conflict we compare belligerent countries (that are not simultaneously involved in other conflicts) to never-treated control countries, include conflict-country fixed effects to absorb time-invariant determinants and conflict-region-year fixed effects to capture regional time trends.

GDP Collapses – and Does Not Recover

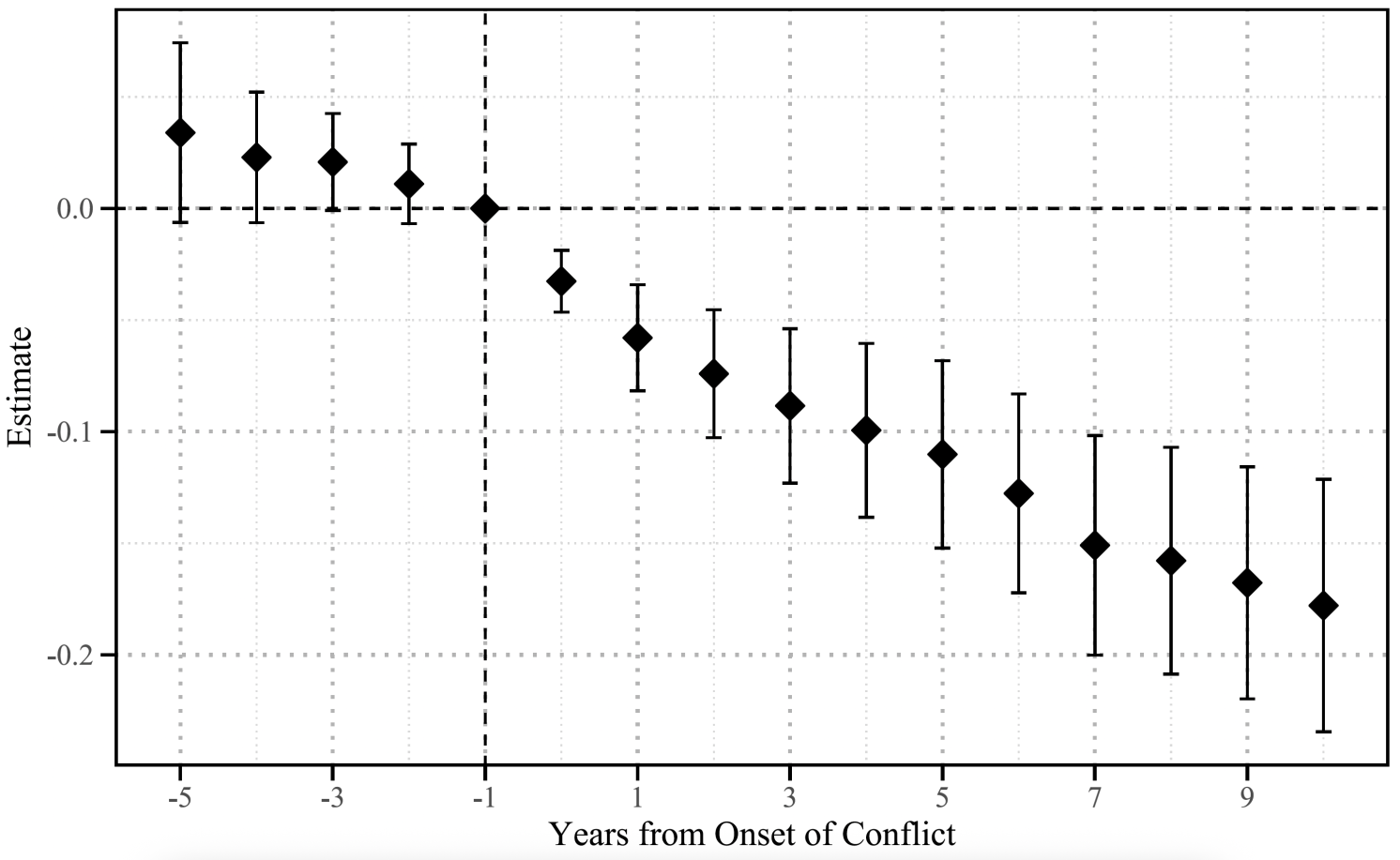

On average, we find that real GDP falls by about 12% (on average) over ten years for treated countries relative to control countries, corresponding to an absolute loss of more than $28 billion (in 2015 prices). At the onset of conflict, the drop is modest (≈3.3%), but then the contraction deepens to about 16% after ten years. Consumption and investment fall sharply; exports fall by 12% and imports by 7%; and the current account deteriorates by around US $2.1 billion.

Figure 1 Effect of conflict on GDP

Conflict is associated with a destruction of capital stock. Consequently, one might expect investment to bounce back due to the higher marginal productivity of capital. Instead, we observe a collapse: real investment falls by around 13%, and real domestic credit drops by 20% – larger than the output loss. Lending rates do not fall, ruling out weak demand and pointing instead to tightening credit supply.

We interpret this as evidence that war erodes collateral values and constrains borrowing, particularly in lower-income economies with shallow financial markets. We also find that the adverse effects are much stronger for low-income countries: investment falls more, trade disruptions are larger, and the import-intensive nature of capital goods in such economies magnifies the shock.

Fiscal Collapse and the Short-Term Debt Trap

War also puts enormous strain on public finances. We document that real government revenues fall by about 14%, while real government debt declines by around 9%, despite nominal debt rising in local-currency terms. Meanwhile, government expenditures remain roughly stable – so the debt-to-GDP ratio stays constant – but the underlying real dynamics reveal fiscal fragility.

We also show that the share of long-term debt falls by about 2.2 percentage points (≈1.2% of GDP) as governments shift toward short-term debt to deal with risk and constrained access. This shift is economically significant – governments shift 1.2% of GDP from long-term to short-term debt – and is associated with a higher rollover risk, which makes these already depressed economies more vulnerable to financial crises.

Inflation: The Silent Tax of War Finance

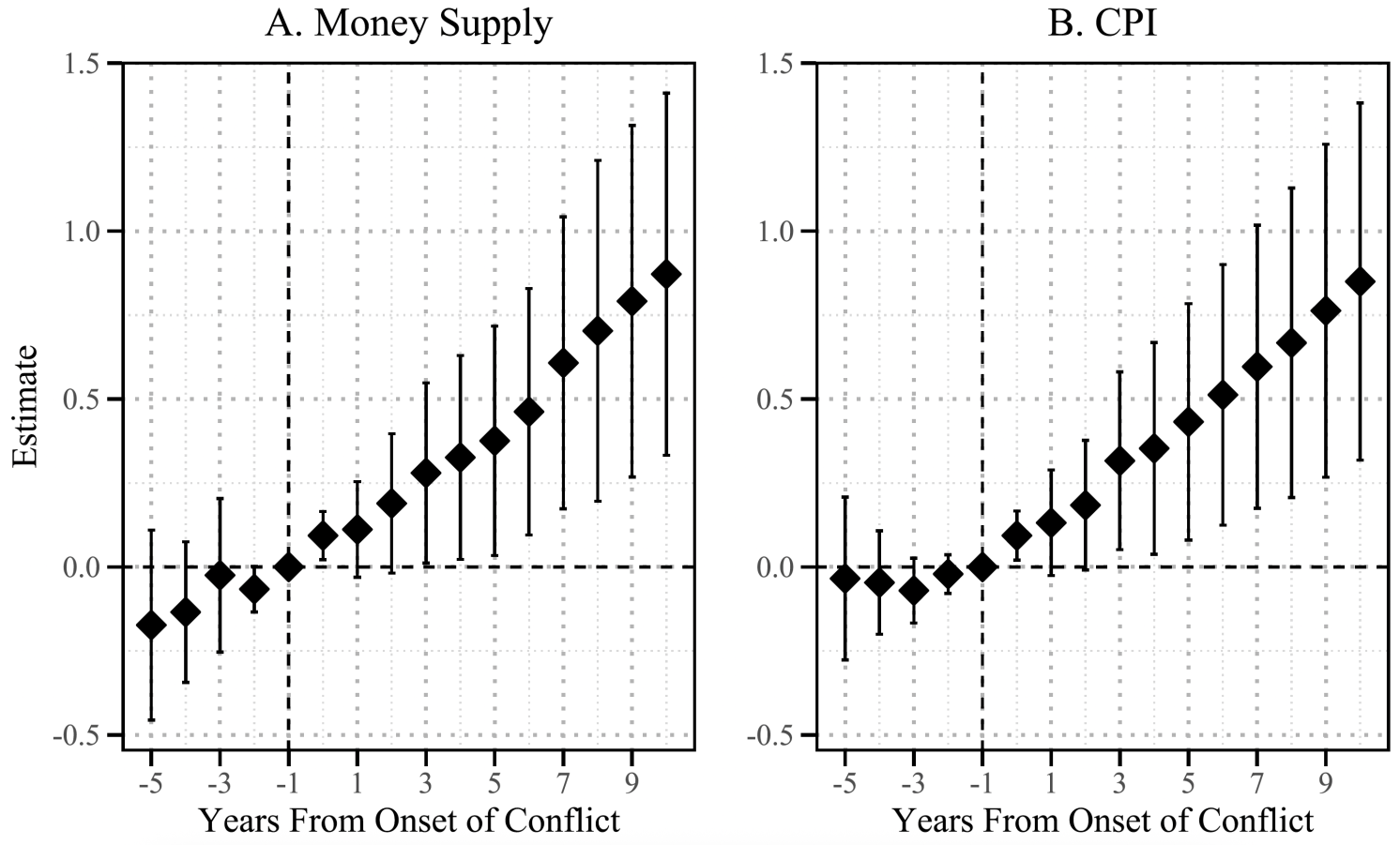

In the decade following the onset of conflict, we observe that the consumer price level rises by about 62%. In comparison, the nominal money supply increases by about 67%, yet real money balances remain unchanged. This pattern is consistent with inflationary financing of government deficits rather than real cash hoarding. War thus triggers a regime of fiscal dominance: deficits, monetisation, and inflation feed into each other.

Figure 2 Effect of conflict on CPI and money supply

Policy Lessons: The True Cost of War

Policy Lessons: The True Cost of War

The main takeaway is this: the costs of war are not temporary disruptions; they are large, persistent, and multi-dimensional. Wars do not simply destroy capital and infrastructure; they undermine the very financial and monetary foundations on which modern economies rest.

For policymakers facing rising geopolitical risk and a return to major military mobilisation, two points stand out:

- Maintaining credible fiscal and monetary frameworks matters even – or especially – in wartime, because the legacy of war depends on how it is financed.

- Reconstruction is not automatic: without access to credit, stable institutions, and affordable capital goods, economies may remain in the slump for a decade or more.

In short, war may end with treaties, but its economic scars endure long after. Recognising the persistence of these scars should shape both how we wage and how we recover from conflict.

See original post for references

Hi five, Hy Minsky

I’m sure this is all correct, but the really disastrous consequence of war is environmental. Many of the landmines and cluster bombs the US so liberally spread across Cambodia and Vietnam are still there. Thanks to John F Kennedy’s enthusiastic promotion of Operation Ranch Hand, large areas of Vietnam and South East Asia were poisoned by chemicals: the same chemicals were dumped on Colombia and other South American countries during the US “war on drugs.”

Whatever the outcome of NATO’s war against Russia in Ukraine, that country will suffer the consequences of war for an indefinite number of years. It is easy to plant mines and drop bombs. It is a slow and painstaking process to find and deactivate them. Goodbye farmlands.

That as well, I agree. And not to forget that Laos remains the most bombed country in history. I recall reading about the use of DU munitions and other toxic measures in the destruction and occupation of Iraq. Speaking of the war on Iraq, I see that Dick Cheney died, the headlines on BBC, Guardian etc. heap praise on the great leader of GWOT. Typical but typically sickening as well. He can go hang out with his hero Henry Kissinger

Is this still the case after Gaza?

It’s a bit of a stretch to compare Laos to Gaza. What’s the point? One is an entire country (236 Mm^2), the other is a couple of cities (0.63 Mm^2). One was subject to B-52 carpet bombing, the other to ‘precision’ bombing using only one bomb per strike. (each B52 carried up to 100 bombs per mission, attacks were typically many aircraft, carried out over multiple years) It’s a rotten apples to rotten oranges – both are bad, why try to make one ‘worse’ than the other?

On that note a German text … 🙄

use google-translate

Bombs, drones, artillery – how the war in Ukraine is fueling climate change

October 28, 2025

by Susanne Aigner

“(…)

From February 24, 2022, to February 23, 2025, 237 million tons of carbon dioxide were emitted in Ukraine as a result of the war. This corresponds to the amount of climate-damaging greenhouse gases released by Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia in one year.

This is the conclusion reached by Dutch climate researcher Lennard de Klerk and his team in a recent study entitled ” Climate damage caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine “. According to the study, the climate damage caused by the war now amounts to over 43 billion US dollars.

(…)”

pdf of the study:

Since it´s a Dutch study the culprit is in the headline

– Almost all authors are from Ukraine –

Was that really necessary from a purely scientific view?

I.Don’t.Think.So.

CLIMATE DAMAGE CAUSED BY RUSSIA’S WAR IN UKRAINE

24 February 2022 – 23 February 2025

By the Initiative on GHG Accounting of War

October 2025

https://climatefocus.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/ClimateDamageinUkraine.pdf

Authors:

Lennard de Klerk, Lead author Initiative on GHG accounting of war

Mykola Shlapak, Initiative on GHG accounting of war

Sergiy Zibtsev, National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine,

Regional Eastern Europe Fire Monitoring Centre

Viktor Myroniuk, National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine

Oleksandr Soshenskyi, National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of

Ukraine, Regional Eastern Europe Fire Monitoring Centre

Roman Vasylyshyn, National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine

Svitlana Krakovska, Ukrainian Hydrometeorological Institute

Lidiia Kryshtop, NGO “PreciousLab”

Rostyslav Bun, Lviv Polytechnic National University

Leroy Farg, Cereza Analytic

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the following organisations for their contributions and insights:

Ministry of Economy, Environment and Agriculture of Ukraine

National Center for GHG Emission Inventory of Ukraine

Conflict and Environment Observatory

Kyiv School of Economics

One Click LCA

FlightRadar24

Disclaimer:

The Initiative on GHG accounting of war was founded in March 2022 and is a group

of experts in carbon footprinting. The Initiative has prepared five subsequent assessments

of the war in Ukraine while also researching other ongoing armed conflicts.

Recently, the Initiative has been focussing on the impact of increased military spending

on military emissions. The Initiative cooperates with the Ministry of Economy, Environment

and Agriculture of Ukraine but does the assessments independently and receives

no instructions from the Ministry or other organisations.

In Russia, the economy is only growing during the current conflict. These economists are probably not aware of what is happening

Yes, the economists are comparing the past to the present. And presently, Russia is strategically destroying industrial/living capacity (electricity generation) as well as atritting manpower in ways not seen. All the while avoiding mass damage to its industry and lifestyle with an exquisite air defense capability.

Ukraine, however, will meet all the consequences outlined in the article, and then some.

Yes, and the US economy seemed to do ok after World War II. And Britain did ok after its many wars, until the US gutted it in WWII

So it looks like a skewed study to me. Perhaps it’s obliquely a bit of Russia bashing.

Someone smarter than me observed, “war made the state and the state made war” … 🤨

“If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, it expects what never was and never will be … The People cannot be safe without information. When the press is free, and every man is able to read, all is safe.” – Thomas Jefferson

“America will never be destroyed from the outside. If we falter and lose our freedoms, it will be because we destroyed ourselves.” – Abraham Lincoln

“A highwayman is as much a robber when he plunders in a gang as when single; and a nation that makes an unjust war is only a great gang.” -Benjamin Franklin

“No protracted war can fail to endanger the freedom of a democratic country.” -Alexis de Tocqueville

. “War against a foreign country only happens when the moneyed classes think they are going to profit from it.” -George Orwell

“The essential act of war is destruction, not necessarily of human lives, but of the products of human labor.” -George Orwell

“A state of war only serves as an excuse for domestic tyranny.” -Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

“It is a universal truth that the loss of liberty at home is to be charged to the provisions against danger, real or pretended, from abroad.” -James Madison

The best way to stop a war is not to start one