Yves here. At some point, this housing price trajectory will come up against Stein’s Law: That which can’t continue, won’t. If nothing else, demographic trends and affordability limits in the public will constrain increases. But the stall could take a while to arrive.

By Yujiang River Chen, Bevil Mabey College Associate Professor in Economics, St Catharine’s College University Of Cambridge and Coen Teulings, Emeritus Distinguished Professor of Economics Utrecht University. Originally published at VoxEU

House prices have increased sharply in many advanced economies, often leading to populist revolt and social crises. This column argues that agglomeration externalities foster urbanisation and knowledge spillovers, which generate high location premiums and can account for the increase in house prices. Policies to address the lack of affordable housing include building smaller houses in cities, providing efficient public rail transport for commuting, and pricing parking for residents in cities appropriately.

The worry about the steep increases in house prices in most OECD countries is widespread (e.g. The Economist 2024, Wolf 2021). The shortage of affordable housing has played a major role in recent elections and is contributing to the global populist revolt. Political parties and policymakers are struggling to formulate an adequate response to what is perceived as a major market failure and social crisis.

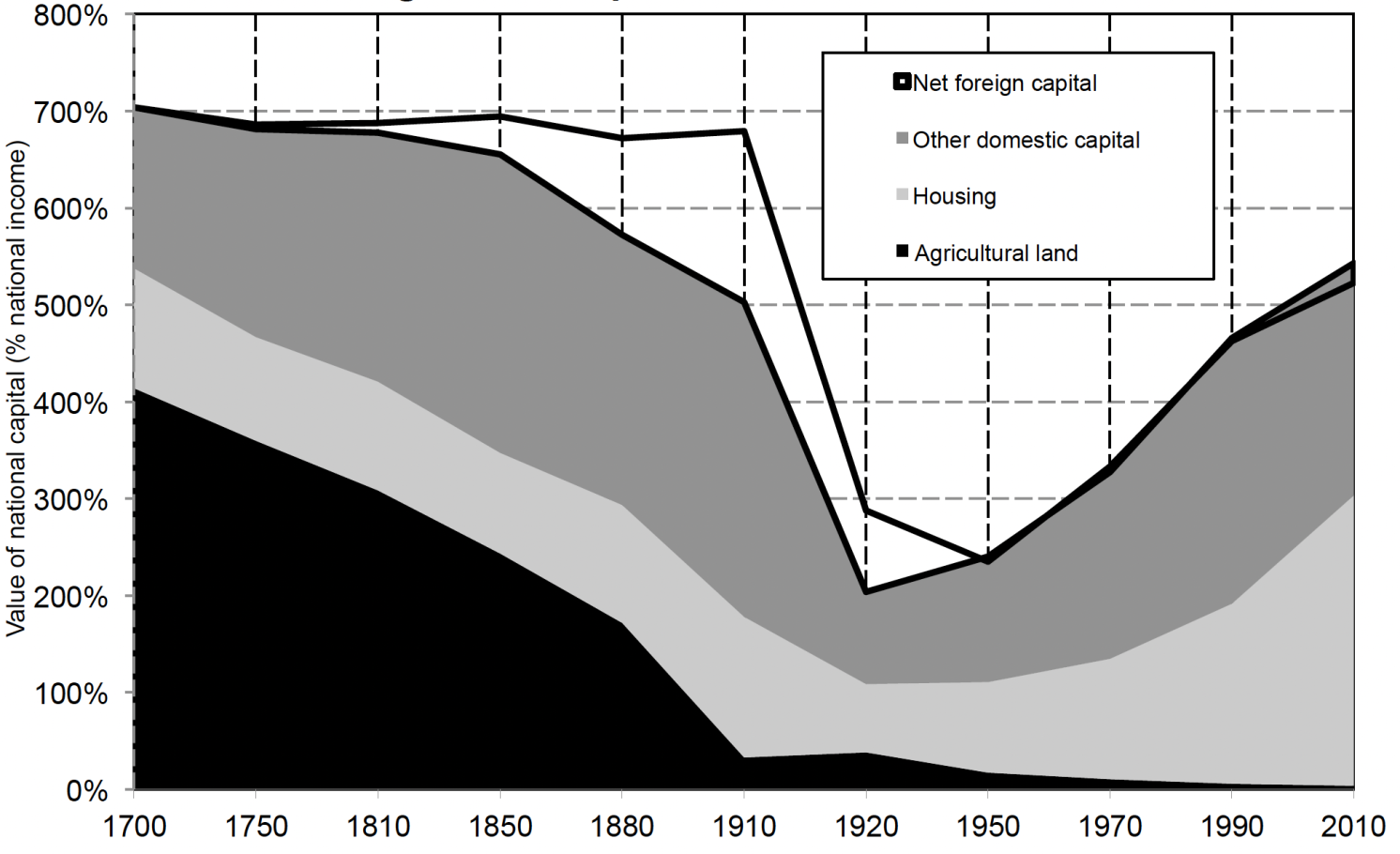

The data in Piketty’s (2014) Capital in the 21st century show that the rising share of housing in the capital stock started as far back as the 1960s/1970s (Figure 1). This phenomenon is not easy to explain. One would expect house prices to move in parallel with construction costs in the long run. Though there might be some increase in relative construction costs, it seems unlikely that this explains the secular upward trend.

Figure 1 Housing takes a rising share of the capital stock in recent decades

a) UK

b) France

Source: Piketty (2014)

We offer an alternative explanation for the rising share of residential real estate in the capital stock. Our explanation is akin to real estate brokers’ well-known answer when asked to list the three most important factors for the value of a property: location, location, and location. Agglomeration externalities foster urbanisation and yield high location premiums, which are embedded in the value of the housing stock. Location premia introduce a wedge between construction costs and house prices. As we shall argue, this phenomenon is the main reason for the increase in house prices. It is deeply rooted in the unprecedented growth of capitalist economies over the past two centuries and the prosperity of OECD countries. It relates to the growing shares of R&D on the one side and marketing/sales on the other side of the value chain (Baldwin and Ito 2021). Both parts of the value chain strongly rely on knowledge spillovers.

Human Capital and Economic Growth

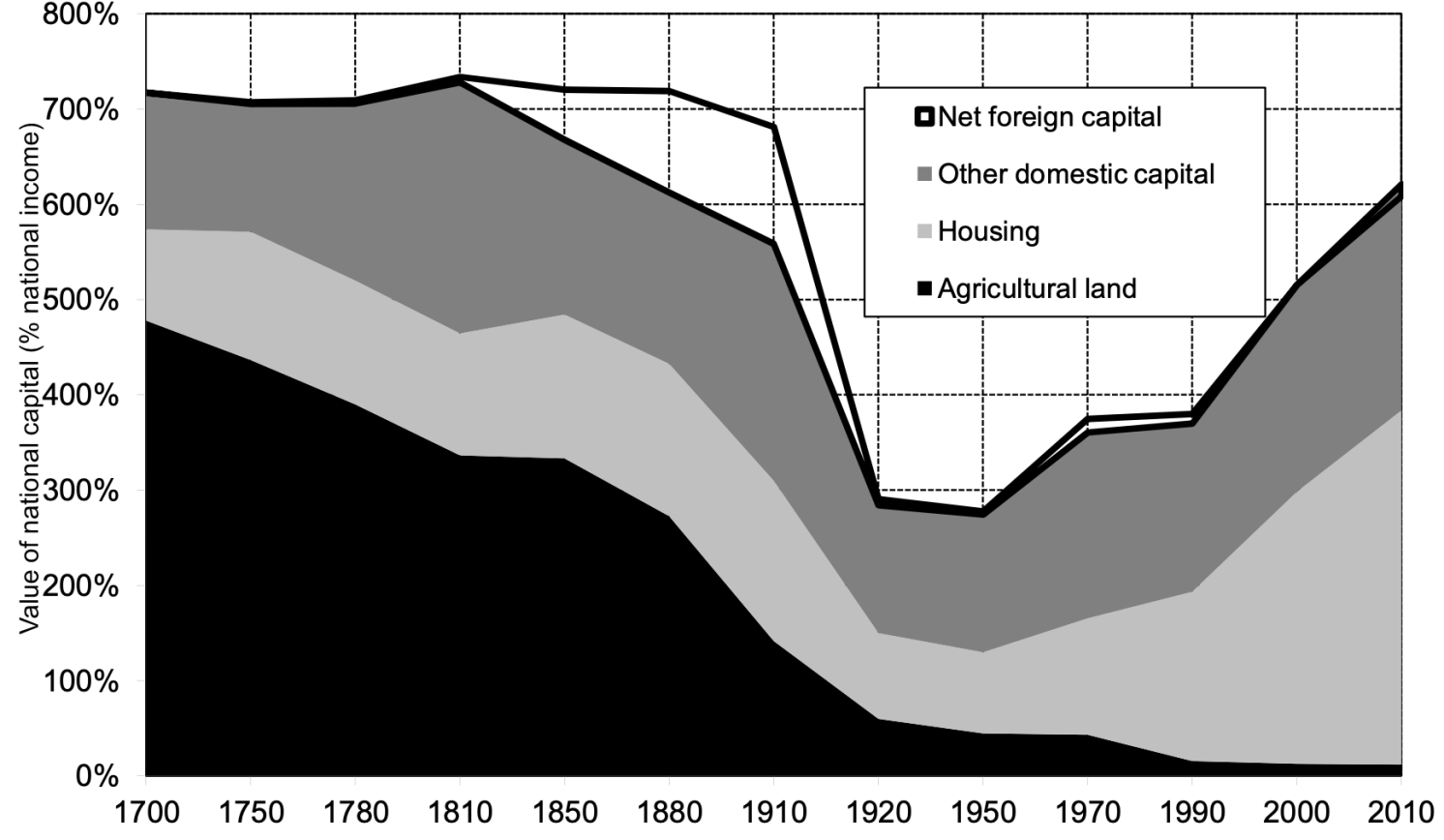

Around 1800, at the start of the capitalist/industrial revolution, differences in GDP per capita across the world were rather small, in the order of magnitude of a factor of four. Moreover, it was not that much different from what it had been in the richer part of the Roman Empire 1800 years earlier. For two centuries, the Netherlands had been twice as rich as most other parts of the world, but this was just an isolated harbinger of what the next two centuries would bring. When the capitalist revolution gathered steam during the 19th century, first in the UK, and not much later in the rest of Western Europe and in the US, GDP per capita exploded in these parts of the world, while there was hardly any effect elsewhere. This divergence continued for the next two centuries, leading to the wide dispersion in GDP per capita between countries observed today and documented in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Strong correlation between GDP per capita and average years of education across countries, 2023

Source: Our World in Data based on UNDP, Human Development Report (2025); Eurostat, OECD, IMF, and World Bank (2025)

Lucas (1988) asked how this could have happened. Standard economic theory would predict convergence rather than divergence of GDP per capita. As technology can be easily copied, differences in GDP per capita must be due to cross-country heterogeneity in the capital stock per worker. But then countries with high capital intensity face a low return to capital, making investment in these countries less attractive than in countries with low capital intensity. This should lead to convergence, a prediction that was clearly at odds with the data. The inevitable conclusion was that technology was not as easily transferable as thought previously, an analysis pre-empted by Arrow’s (1962) analysis of the economics of learning by doing: new technology was mastered, largely by practising rather than by divine inspiration.

This analysis showed the relevance of large, localised knowledge spillovers, where spatial proximity to the location of inventions is the critical factor. Lucas pointed to the role of agglomeration in cities for knowledge spillovers. He cited Jacobs’ famous (1961) book The Death and Life of Great American Cities as an analysis of what spatial structures of cities were most conducive to the generation of these spillovers. In subsequent work with Rossi-Hansberg (Lucas and Rossi-Hansberg 2002), they investigate the implications for the internal structure of cities with a commercial central business district (CBD) surrounded by residential suburbs. Their model has been used extensively, for example in the analysis by Heblich et al. (2020) of the rise of London as the first modern metropolis around 1850 and by Ahlfeldt et al. (2015) of the consequences of the Berlin Wall dividing the city for five decades.

The localised impact of human capital can also be seen from Figure 2, where GDP per capita is plotted against years of education. These data suggest a public return per year of education of about 50%, way above the standard estimate of the private return of about 10%. Gennaioli et al. (2013) report very similar numbers using within-country regional variation rather than the cross-country variation based on Barro and Lee (1996) and shown in Figure 2: within countries, high human capital workers concentrate in some regions and in these regions GDP per capita is much higher. These data support the idea of large externalities of the proximity of high human capital workers. Clearly, the raw data show just correlation, not causality. We return to this issue below.

Cities and Human Capital

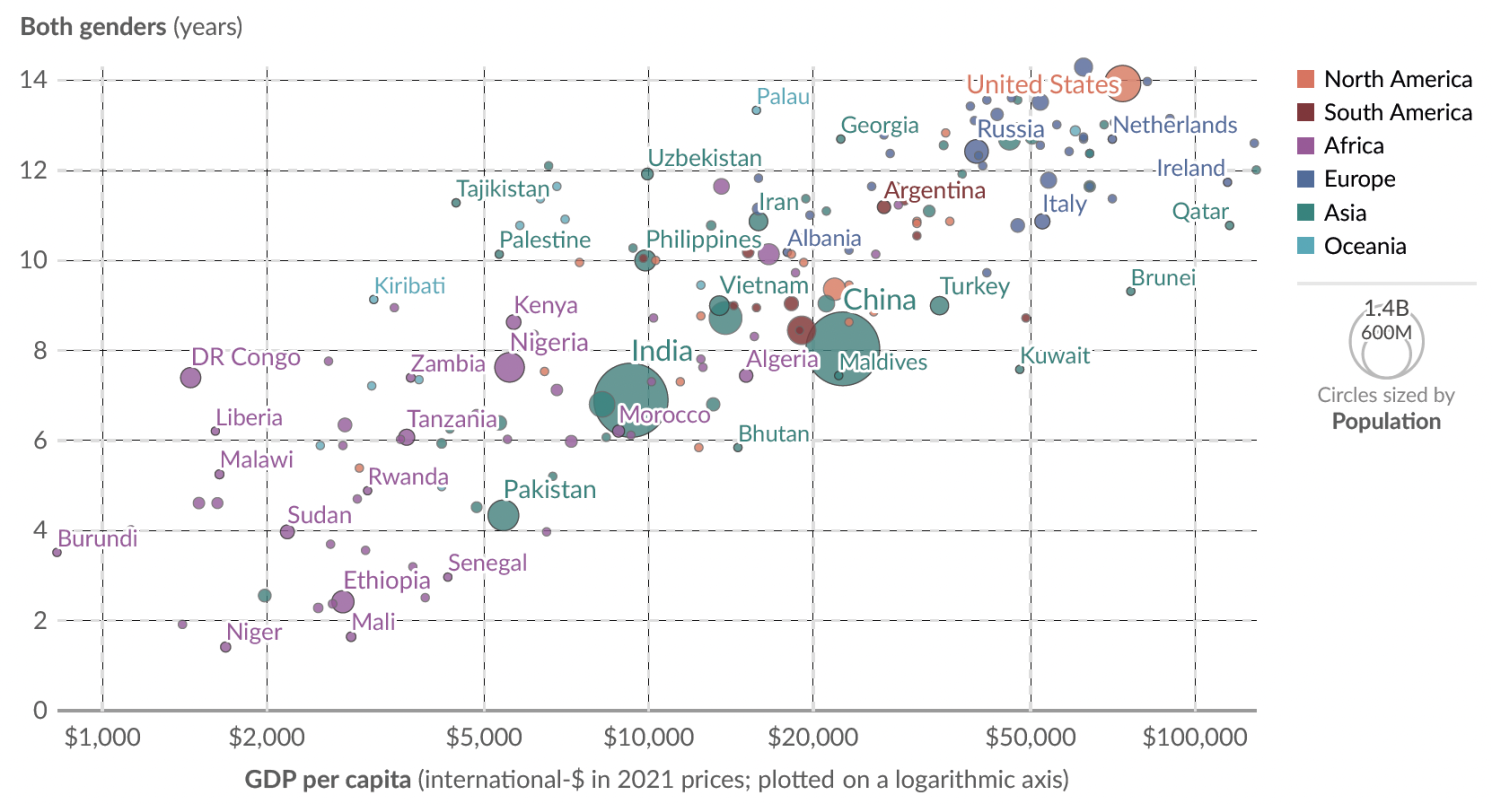

In accordance with Lucas’ (1988) analysis, cities have played a crucial role in economic progress throughout history. Urbanisation increased during periods of exceptional prosperity and declined during subsequent downturns. This pattern is aptly illustrated in Table 1, based on data collected by Bairoch (1988). Belgium was the world’s most urbanised country during the peak of its textile industry between 1300 and 1500. In the 16th century, the Dutch Republic surpassed Belgium and the latter’s urbanisation rate declined. As discussed before, the Netherlands was the most prosperous country during the next two centuries. During this era, it was the world’s most urbanised country, with Amsterdam serving as the leading global port and financial centre. Although the Netherlands remained the world’s wealthiest country well into the 18th century, its dominance – along with its urbanisation rate – gradually waned. It was only around 1850, with its industrial revolution in full swing, that the UK overtook the Netherlands as the world’s most urbanised nation.

Table 1 Urbanisation in European countries closely aligned to economic growth

Source: Teulings and Huysmans (2025), adapted from Bairoch (1988)

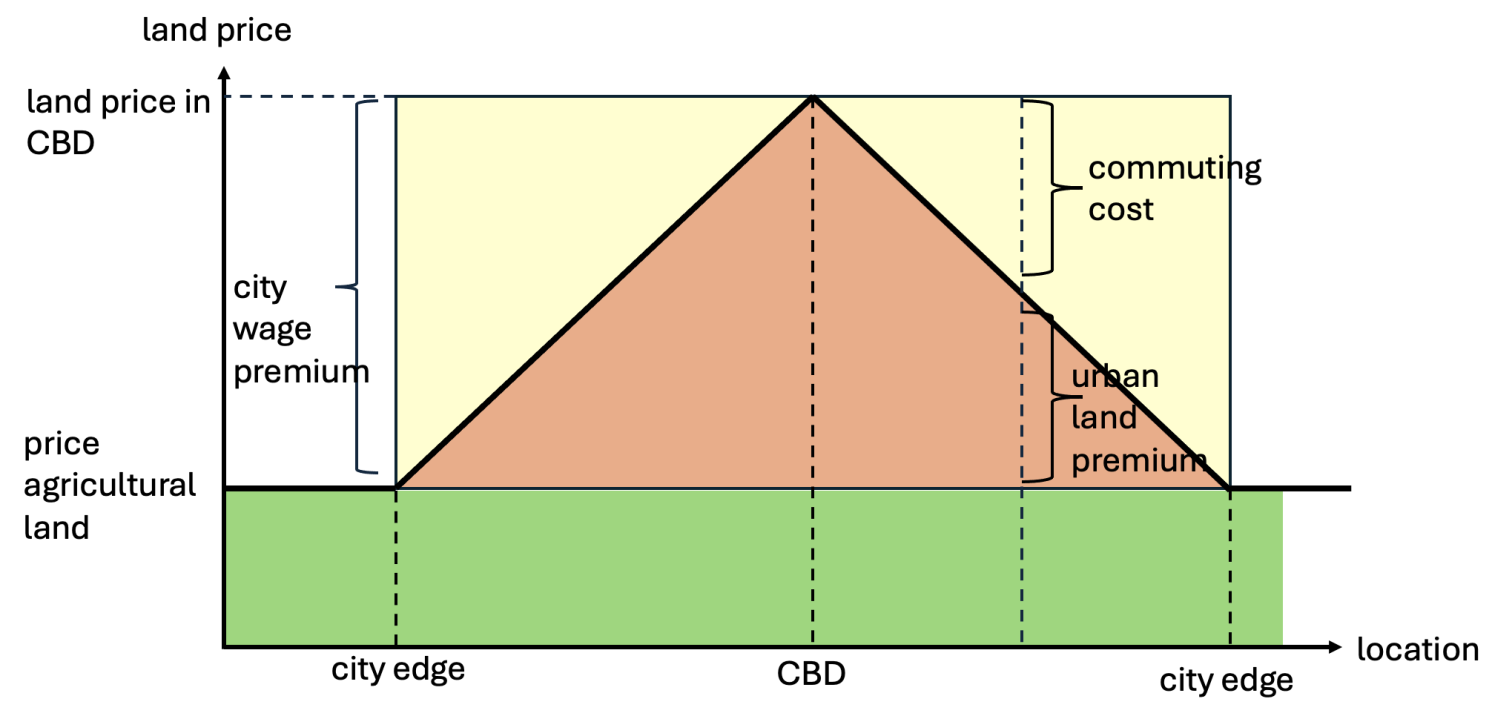

Figure 3 presents a simplified version of Lucas and Rossi-Hansberg’s (2002) model. Locations are reflected along the horizontal axis. The Central Business District (CBD) is in the centre. The vertical axis reflects land prices and wages; for simplicity they have the same dimension. Green reflects wages in the countryside. The higher wage in the CBD reflects the benefit of the agglomeration of workers at one point in space for the generation of knowledge spillovers. Workers, however, need land for residential purposes. They cannot all live in the CBD. They therefore live in the suburbs surrounding the CBD and commute to it. The yellow triangle measures the commuting cost, which increases linearly in the distance from the home location to the CBD: the further away from the CBD, the higher the commuting cost. The slope of the line between the yellow and orange triangles measures the commuting cost per kilometre.

Houses at locations close to the CBD are therefore more valuable since their residents save on commuting costs. At the edge of the city (see Figure 3), the city wage differential is offset by the commuting costs. This model explains the disconnection between house prices and construction costs. Building inside the city’s edge is impossible, as all land is already occupied. Building outside its edge is not profitable because commuting costs from these locations exceed the city wage premium.

Figure 3 A simple model of a city

Source: Teulings and Huysmans (2025).

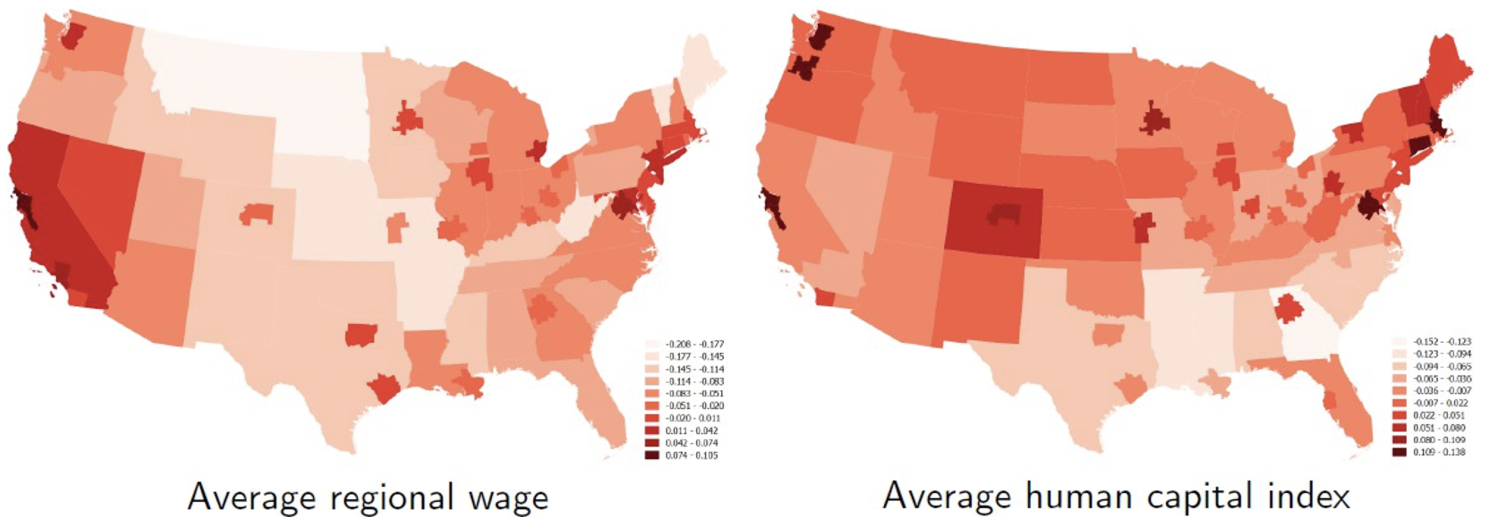

The spatial form of a city with a commercial CBD surrounded by residential suburbs is conducive to knowledge spillovers as it concentrates large numbers of workers in a small area, where in rural areas employment is geographically dispersed. Since knowledge spillovers are more relevant for high human capital workers, these workers agglomerate in cities, just as reported by Gennaioli et al. (2013). Figure 4, taken from Chen and Teulings (2025), shows this pattern for the US for 34 cities and 47 rural areas. San Francisco, Boston, and San Jose turn out to have higher human capital per worker than other cities, and the average city has higher human capital than the average rural area (left panel). The same holds for wages (right panel).

Figure 4 Human capital regionally concentrated, in particular in cities

Source: Chen and Teulings (2025)

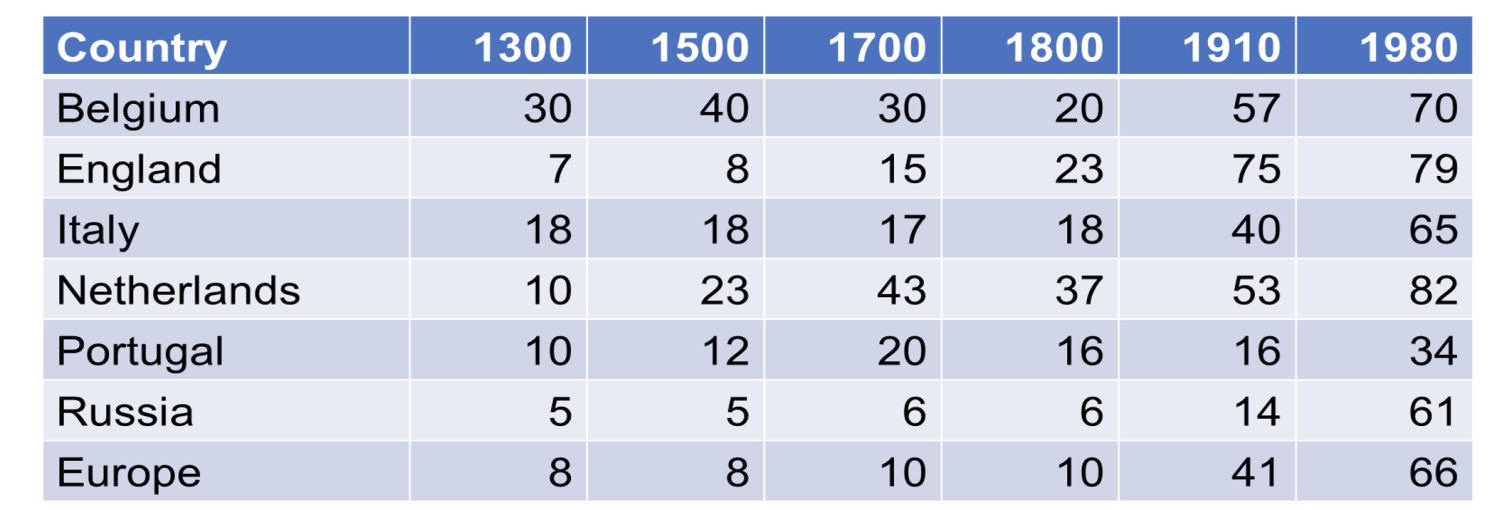

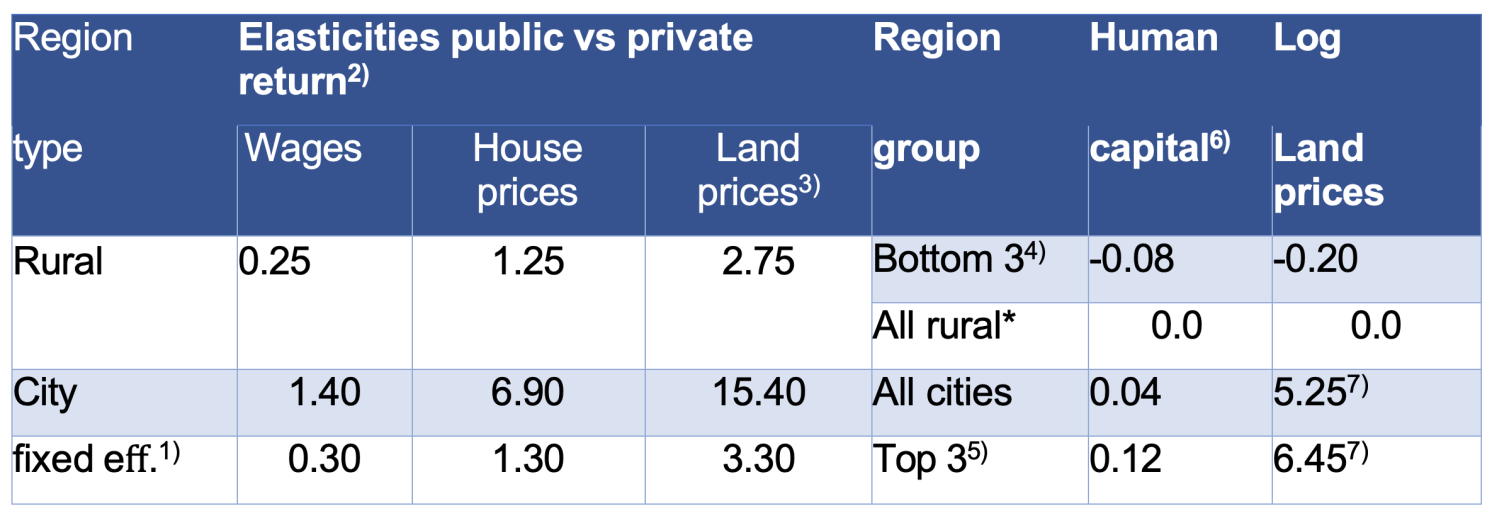

In Chen and Teulings (2025), we use this model. We regress individual log wages on both individual and regional human capital as explanatory variables. The effect of individual human capital measures its private return, while the effect of regional human capital measures its public return.

Table 2 shows the results. The public return adds 25% to the private return in rural areas and more than doubles the private return in cities (see column 2). The interpretation of the regression coefficients is subject to two well-known statistical problems. First, the effect of regional human capital might be a proxy for unobserved individual human capital, thereby overestimating the public return. Second, there might be a common latent factor explaining both why particular regions pay higher wages and why high human capital workers prefer living there. We correct for these problems. If anything, their correction underestimates the public return.

Workers’ human capital therefore has positive externalities for the earnings of their co-workers in the region. The city form reinforces these externalities by bringing these workers together at one location, as predicted by the Lucas and Rossi-Hansberg (2002) model. The natural experiment of the 1974 Carnation revolution in Portugal confirms these conclusions. The rapid modernisation of the country in the subsequent decades led to a specialisation of its only big city, Lisbon, in high human capital activities (Teulings and Vieira 2004).

Table 2 The public return to human capital and land-prices in rural areas and cities

Note: *: reference category. Additional notes: (1) Fixed city effect in a wage regression on individual wages including the regional mean human capital; (2) Public return on average regional human relative to the private return; (3) Using the estimated coefficients in Table 8, λz from Table 7, pr = vr – lr and equation 8; (4) Louisiana, Georgia, Mississippi; (5) San Francisco, Boston, San Jose; (6) Expressed in terms of the private return to this capital; (7) Including the fixed city effect

Source: Chen and Teulings (2025)

When choosing where to live, workers take these positive externalities into account. They prefer regions with high human capital, in particular cities with high human capital per worker, since a high regional human capital increases their pay. There must be an offsetting force that prevents everybody from moving to the city with the highest human capital. This offsetting force is house prices, or equivalently, the price of underlying land. They adjust as to make workers indifferent between regions. Indeed, workers get better paid in cities – in particular in cities with the best educated workforce – but buying or renting a house in these cities is more expensive. To test this idea, we regress regional log house prices on average regional human capital (see Table 2, column 3). Since housing services take only a small fraction of workers’ budget, the effect of human capital on house prices must be a factor of five larger to offset the positive effect on wages, as is found empirically. But since housing is much more expensive in cities, workers will substitute away from housing services to other consumption. The residential density is therefore higher in cities than in the countryside, making the effect on land prices even larger (see column 4). The final two columns show the implications for human capital and land prices in four groups of regions: rural areas and cities, and within rural regions the bottom three in terms of human capital (Louisiana, Georgia, and Mississippi) and within cities the top three (San Francisco, Boston, and San Jose), where rural areas are taken as a point of reference. Land prices are 6.45 log points (a factor 600!) higher in the top three cities than in the average rural region. Using a one-third land share in the cost of housing services implies that a square metre of housing is eight times more expensive in the top three cities than in the average rural area.

We use the model for two counterfactuals. First, what would happen if there were no cities and all regions were organised as rural areas with dispersed employment and therefore far smaller knowledge transfers? Second, what would happen if human capital was not clustered in particular regions that specialise in knowledge spillovers, but instead was spread equally across the country? In both cases, the answer is that GDP would be approximately 10% lower; in welfare terms, the effect is smaller, as part of the city wage premium is compensation for the commuting costs.

Policy Options

The surge in house prices over the last half century documented by Piketty (2014) is therefore not much of a surprise; it can be readily explained by the growing importance of knowledge spillovers and human capital externalities and their crucial role in the growth of capitalist economies since 1800. These regional externalities generate rents which are captured largely by the owners of land close to CBDs. One might argue in favour of the Henry George taxation of these rents. This makes housing services at these locations a source of revenue for governments, but then housing in city centres will remain scarce and therefore expensive for individual residents.

Figure 4 suggests that a city can be extended until the point where the city wage premium is equal to the commuting costs. Lange and Teulings (2024) argue that vacant land at the edge of successful cities carries a substantial option value due to the irreversibility of construction. Better delay construction for some time than to build early at too low densities. This option value drives a wedge between the city wage premium and the commuting costs at the edge, raising house prices at the edge of the city. This mechanism adds to the delay of new construction in response to upward shocks in cities’ house prices. The higher the growth rate of the city, the larger the option value and the higher therefore the delay. Our diagnosis therefore provides little hope for those arguing in favour of massive construction at the edge of cities to increase the supply of residential floorspace in cities and to bring down its price.

To the contrary, the Lucas-Rossi-Hansberg model implies that residents buy more floorspace than is efficient (Rossi-Hansberg 2004). Cities’ high house prices reflect the advantage that an extra worker would derive from living close to the CBD and being able to benefit from the knowledge spillovers generated by the mass of workers concentrated in the CBD. However, house prices do not reflect the advantage for other workers in the CBD from the additional spillovers generated by this extra worker. Including this externality in the price would reduce the consumption of floorspace even further, contributing to more efficient knowledge spillovers.

There is a growing literature (e.g. Glaeser et al. 2005, Duranton and Puga 2023) documenting the effect of excess regulation on new construction. This regulation would stall new construction. Apart from a substantial institutional hysteresis, this literature holds insider interests of incumbent residents responsible for this excess regulation. Insiders block regulatory reform as new construction would erode the value of their property, either through the negative externalities of nearby construction of new houses or through the negative general equilibrium effect of additional supply of housing on the price of existing real estate.

The credibility of this argument depends on the political scale at which this regulation is set. It would not be excessively restrictive if the regulation is set at the level of the urban agglomeration as a whole; the agglomeration would internalise all relevant externalities. Cities run industrial policies to attract corporate headquarters and the like for the benefit of their knowledge spillovers. They usually provide the transport infrastructure for commuting to the CBD; the rollout of Canary Wharf in London is an example. Some cities do even impose minimum density constraints on new urban development, as theory predicts.

However, when the regulation is decided at a lower political scale, it will not internalise these externalities. 1 Local agglomeration benefits will prevail – for example, the desire of well-to-do neighbourhoods to keep out lower income strata. Minimum lot size regulations are a perfect tool for this. While this argument may hold for some luxury neighbourhoods, one can doubt whether this plays a major role at the aggregate level of the city – in particular in Europe, where city planning is more centralised.

Our analysis yields a number of alternative policies that might help to alleviate the popular uproar over the lack of affordable housing. Since house prices per square metre cannot be expected to come down, the first policy is to build smaller houses in cities. Those who want larger houses should move to faraway suburbs.

The second policy is to provide efficient public rail transport for commuting. This recommendation has two motivations. First, better public transport reduces commuting costs per kilometre. For a constant city wage premium, this extends the edge of the city (see Figure 3). Second, private car transport is highly land-intensive compared to public rail transport, due to both road construction and parking space at work locations in the CBD and home locations in the suburbs. Rail transport requires a large scale, but is particularly land-efficient, which makes it highly suitable for large cities. This land use crowds out commercial and residential land use and therefore reduces the scope for knowledge transfers. Jane Jacobs built her career on her protest against the construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway. Smaller European cities like Amsterdam and Copenhagen were successful in pushing back car use. Larger cities like London and Paris are now copying this model.

The third policy is related to the second. Ossokina et al. (2025) show that the parking fees at shopping malls are largely proportional to local land prices and roughly consistent with a rate of return on the asset value of land of 5%, as one would expect for commercial parties who face a trade-off between using the land for either parking lots, floorspace for shops, or residential construction. Most cities, however, heavily subsidise parking at home locations. Where car ownership is no longer an obvious choice in larger cities, one wonders why city governments choose to offer residents parking spaces almost for free while the actual cost is €1000-€5000 per year in larger cities, corresponding to an asset value of €20,000-€100,000. By making parking free or almost free for residents, this right is linked to the ownership of a house. Its value makes up 10-20% of the total value of the house. For those without a car, this expenditure is wasted. Why should residents without a car subsidise car owners?

See original post for references

What about de-financialization? Sometimes the simplest solution is the best. Put a cap on mortgages and ownership limits (via taxing or other means).

The problem with capping financial rules for housing costs is that it can benefit cash buyers, whether they are outside investors or just those who have inherited houses elsewhere. Plus, it disincentivises much needed investment in new stock if a city is growing. In that case, then the government must step in to build (or at the very least, step in to release land for small or individual builders).

Ultimately, it comes down to friction in land and property markets usually results in underbuilding where its really needed (existing urban areas), and often overbuilding further out (during boom times), where land is cheaper and there are often fewer legal/regulatory barriers. Managing urban housing requires very strong and very well funded local and regional governments, but even this is often not enough – as I mention below, Singapore is probably one of the few big cities that has to some degree ‘solved’ the problem, but its also to some degree a special case.

I’m not sure this article explains why housing is increasing so much as a percentage of the capital stock so much as it explains why there is such a huge differential between urban and non-urban prices. One possible explanation to add to this is that for many decades there has been much higher productivity gains in the ‘knowledge’ industry than in other sectors – hence likely a greater concentration and focus on those geographically linked areas where there are agglomeration benefits.

One constant feature of economic geography is just how ‘sticky’ big urban centres can be. Look at a list of the great cities of today, compare it to a century ago, or even many centuries ago, and there is remarkably little change. Cities like London or Paris or Tokyo or New York or Shanghai keep their proportional wealth and growth even as the original reason for their prosperity has long passed into history. Some cities go through several waves of transformation and destruction (Berlin, for example), and yet still maintain their relative importance. The obvious reason is a combination of the sunk cost of infrastructure (building new cities from scratch is extremely expensive) and, most importantly, the gravitational attraction of knowledge based industry reinforcing itself. Conventional economics would suggest that the cost differential of property, wages, etc., should geographically even things out, yet in reality this rarely happens, even when governments devote sometimes vast resources to reinforcing ‘weak’ regions or even transferring capitals (this rarely seems to work well).

To some degree, the article reinforces something that should be quite obvious – people like living in the great cities, and they are unquestionably where the big opportunities lie for the ambitious, but there are physical limits to how much people they can take – and it is almost inevitably reflected in very high costs. Building fast, high and cheap can alleviate some problems, but even that has its limits, as anyone who has checked out housing costs in, say, Hong Kong, will confirm. Singapore is maybe one of the very few examples of a growing and rich city that has managed to some degree to manage the balance of keeping housing costs relatively low, and much of this comes down to highly managed population inflows (something rarely discussed much on this topic). Most other examples quoted (such as Tokyo or Vienna) are, probably not coincidentally, cities where there is a relatively modest population growth combined with a historically high level of housing stock. For big cities going through a fast growth stage, managing housing costs is exceptionally difficult, almost all interventions seem to almost inevitably result in unexpected and often unwanted consequences.

City versus rural is a huge topic that the above is reducing to simple explanations. But I think you are right that cities arise out of practical considerations–i.e. access to a port or a river–and they keep reinventing themselves once the infrastructure is there. The economy of NYC has changed over time even as the Brooklyn bridge persists.

I’m not sure though that the above assertion that people live outside cities only because of housing costs or they have to do so holds up. Here in the US the automobile and now the internet have changed these calculations and given access to “knowledge” and even knowledge jobs without living cheek by jowl.

Here’s suggesting that many suburbanites tolerate those long commutes because our urge for the social wars against our urge to be individuals. I used to live in Atlanta which rather than densifying now spreads across much of north Georgia.

I also see zero acknowledgment in this piece that the metropole always extracts from its periphery.

Here in the USA we have many abandoned or low population towns throughout the Midwest and even in Northern New England. The reasons are consolidation of agriculture into huge mechanized farms, loss of manufacturing and the enormous growth of the service/consumer sector. You don’t just open up nail shops, barber shops, shopping malls restaurants, landscapers, and of course banks or even hospitals in low density isolated areas. We live 40 miles from Boston and the average home price here is $1million up from $50K 50 years ago. But I could buy an equivalent home in an isolated area for $100k. But now I’m old and need services.

In the case of Singapore I think the term “highly managed population inflows” is a bit overly kind. The majority of construction workers there are not Singaporean residents, they are not well paid nor do they vote in elections. Subsequently they themselves live in cramped conditions that the average Singaporean would not accept. Singapore uses cheap labour from predominantly India, Phillipines and Thailand to constrain their costs for much work they consider menial.

Reads as much as a neoclassical economists just-slightly-more-sophisticated justification for keeping things largely on the path they’re already going:

Smaller/crappier houses with no parking/garden/privacy, keep pushing workers into the rat race in the city, strip away safety/living-standards/community-oriented regulations, assumption of upward prices only, cars becoming an unobtainable luxury (not synonymous with better public transport).

The idea of knowledge exchange/transfer in a city location was a lot more relevant in the past, and it still is relevant, but I think less so now. I would place the primary reason for remote-capable work being done on-site, and centralized in cities, as increasingly financial/speculative in reasoning – less productivity/growth oriented since Covid.

As usual in articles like this, no mention of social housing – market is king.

If we’re to talk about ‘knowledge sharing’ in a locality as well, then we should also talk about influence-peddling and corruption, when e.g. financial centers are mixed with or nearby political centers – the IFSC tax haven in Dublin is like a 1.5 kilometre long vipers nest of HQ’s for many of the worlds most corrupt and disreputable financial companies.

Not the kind of ‘knowledge spillovers’ and revolving doors we want for our societies – and arguably _the_ source of many of the ills the article discusses.

benefit from the knowledge spillovers generated by the mass of workers concentrated in the CBD

Yea OK sure

Define capitalism two ways – Industrial and financial….. Real capitalism and ficticious…..

What knowledge spillovers???? how to cast a tile or how to engineer financing.

Real capitalism benefits from infrustructure, ports, energy production, access to raw materials and talent. It is the actual conversion of available natural inputs by human hands into actual physical products it is what defines wealth and wealth creation not money which is a measure of wealth and constitutes a large portion of GDP. Real wealth plus fictitious wealth. How would GDP look if the measure of finance capital was subtracted from the measure of real wealth. I remember years ago that 40% of all profits went to the finance sector-

Finance capital adds nothing to the riches of the country, but merely takes toll from those who do employ labor and produce wealth.

Real estate is in the hands of finance capital gamblers who have no interest in land. To them it is just a pile of blue chips on a roulette wheel. Add in the tax breaks, political coruption and leverage of public spending into private profit.

Take a quick look at which cities boom and bust together over the last xxx years a take note of how they all seem to be the same ones again and again.

Thank you. The article doesn’t touch on rampant financial speculation or where this “capital” comes from in the first place. I will never forget about twenty years ago being pre-approved for a loan amount that was about double what we could actually afford for a house. And of course as NC readers are aware, the bank approving me for this loan wasn’t going to lend me a few hundred K of their own money – they were going to create it out of thin air by keystroke.

Much of what passes for capitalism is the rest of us pretending that capitalists actually have money and agreeing to pay them back with earnings gained by actual work, plus a lot of interest added on for good measure. That just might have something to do with why the rich keeper getting richer and these economic theories so often don’t pan out the way the models say they were supposed to.

I do look forward to the day when the would-be capitalists are shipped off to some small island where the can all play Monopoly amongst themselves and leave the rest of us alone to get on with being productive and enjoying the fruits of our own labor.

This is a nonsense explanation. The authors use worker income as a proxy for human capital, then ‘explain’ higher worker income (and thus higher housing prices) on the basis of cities having ‘higher human capital’. Its a tautological explanation hidden in neoclassical economic jargon.

Yup. The premise also that everyone moving to the city does so because “they will get paid more” elides the reality that for many the choice is move there or have no job at all. But such people are kept invisible behind the scenes at brunch …

When we looked for a house, the one we bought was closer to a city and more expensive on paper. There were cheaper homes 30-45 minutes away in more residential communities. Once you factor in the cost of a daily commute from the suburbs to the city over the life of a 30 year mortgage, with those costs rising all the while compared to the fixed cost of a mortgage, suddenly the house farther away from the city isn’t actually cheaper at all.

Perhaps that has something to do with the flaw in the model…

They sure take a long time getting around to mentioning Henry George, but at least they got there towards the end — not that his idea gets more than cursory attention.

What they assiduously avoid mentioning is public housing a la Vienna or Singapore. Because markets, eh?

Everything I buy in a consumer vein goes down in value almost immediately, so why does an old home built in the 1960’s or even a newer home built a couple years ago hold its value?

I get it that the hallowed ground on which it stands is a lot of the value, but why?

Last time they counted (2021) there were over 61,000 vacant units in San Francisco. There’s empty buildings in every neighborhood in San Francisco. A neighbor of mine in Hayes Valley lives in an eight unit building with the other units empty. I’m sitting in a building on Fell St. next door there’s an empty lot thats been empty since the early 70s. Zombie buildings filled with zombies. Landlords are being subsidized to keep the market from falling.

Rents are dropping in many cities across the country, sunbelt and elsewhere. Some of that is due to oversupply of new units while some is due to declining demand. At some point, there may appear an academic paper showing correlation between self-deportation and rent changes.

There would be an expected ripple effect through lower priced houses, whether rented or owned, as demand declines spread.

Vancouver-based planning academic Patrick Condon discusses why expansion of supply via increased density has made no difference to housing prices in his city.

Extracts:

You are correct that the common expectation is that this problem is solved if you just add new density onto expensive land in the hope of diluting the land price component. But if you just rezone for more density, you find that the main beneficiary of the upzoning is not the renter or owner, but the land speculator. And that the final rental or ownership cost of the new units is no lower, and most often even higher, than the housing units nearby.

That’s not true just for Vancouver; it’s global. Particularly throughout the so-called English-speaking world. Sydney, Australia, just edges out Vancouver on the very top of the Demographia list of the world’s most unaffordable cities when measured against median household income, which are the lowest of any North American centre city by the way.

Simply stated, urban land has the tendency to absorb every nickel of value created by the people living and working above it into its price.

Urban land is a monopoly product and like any monopoly there is little limit on its asset value, a price based on its location in the centre of commerce. “Buy land, they are not making any more of it,” Mark Twain famously said.

…

We are now in the habit of thinking if housing prices are too high it must be a problem of restrictive zoning, or construction costs, or taxes. It’s not. It’s a problem of our gradual return to the norm where land absorbs too much value uselessly, and unrelentingly, into the value of urban land. It’s the return of “landlordism,” really, a problem that the first real economist, Adam Smith, identified 250 years ago.

…

So, anyway, this shift has pushed the values of urban land up and out of sync with regional wages. Housing prices end up escaping their traditionally assumed “real estate fundamental” ratio of four to one, home price to annual wages. That ratio in Vancouver is now 12 to one.

My assertion is this: the only way regions can get control of this out-of-control phenomenon is by exerting control over the land base, and asking for a degree of social benefit to accrue from these global investments. This puts me in a different camp from those who argue that more market-driven density alone will bring down the cost of housing by itself. Sometimes, yes, I have spoken against denser development but not because I’m opposed to density, per se, but because if it can’t deliver affordability, then we must ask whether this particular proposed building is a good precedent to approve.

kind of like a petri dish

100 years later and economists finally (just starting) to catch up to Georgisim. Land value is a public good, created by the public, so should be heavily taxed (>85%). Improvements are separate and can/should still be private. But the value of the location comes from the community!

It seems simplistic to argue that what’s happening with housing prices is simply a matter of location. Urban locations providing easier access to jobs and other resources have been around since the mid 1800s (at least) and are not something that has suddenly popped up in the last 20 years.

IMO the main factor has been the increasing shift of housing from simply being a place to live to being a speculative investment. Recently, in particular, the investing classes have moved heavily into buying up housing stock, driving up the prices (what a great investment!) while making housing unaffordable for people who just need a place to live. As capital becomes concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, this concentrates housing in fewer and fewer hands too.

I remember reading about a housing program in Cuba, I believe it was, that worked as follows. Public housing was constructed by the state, and then could be purchased more or less at cost by people who plan to live in the house. They own the house as an asset, and can sell or bequeath it to family members as they grow old and die, but they cannot sell it to anyone else. The upshot is that the owners are actually owners and have a secure place to live for as long as they need, but there is no “market” for this housing and it does not become an appreciating asset, keeping out the investor and speculative classes. People who own the houses have an interest in keeping them in shape and keeping the neighborhood livable, and the population remains fairly stable and forms tight communities as well.

I have always thought this was a charming idea, perhaps with some tweaks, and serves the primary need of giving people and their families an affordable structure to live in, and a community filled with people who will be there for the long term.