Yves here. I attended a full day of presentations at the Explorers’ Club presenting findings of on-the-ground research from the 2007-2008 International Polar Year. The club’s members were a mix of adventurists and scientists, many of whom had made extended stays in the Arctic. To a person, they were clear then they were seeing extensive and alarming evidence of global. But many also conveyed their love of the harsh beauty of the region.

By Emily Cataneo, a writer and journalist from New England whose work has appeared in Slate, NPR, the Baffler, and Atlas Obscura, among other publications. Originally published at Undark

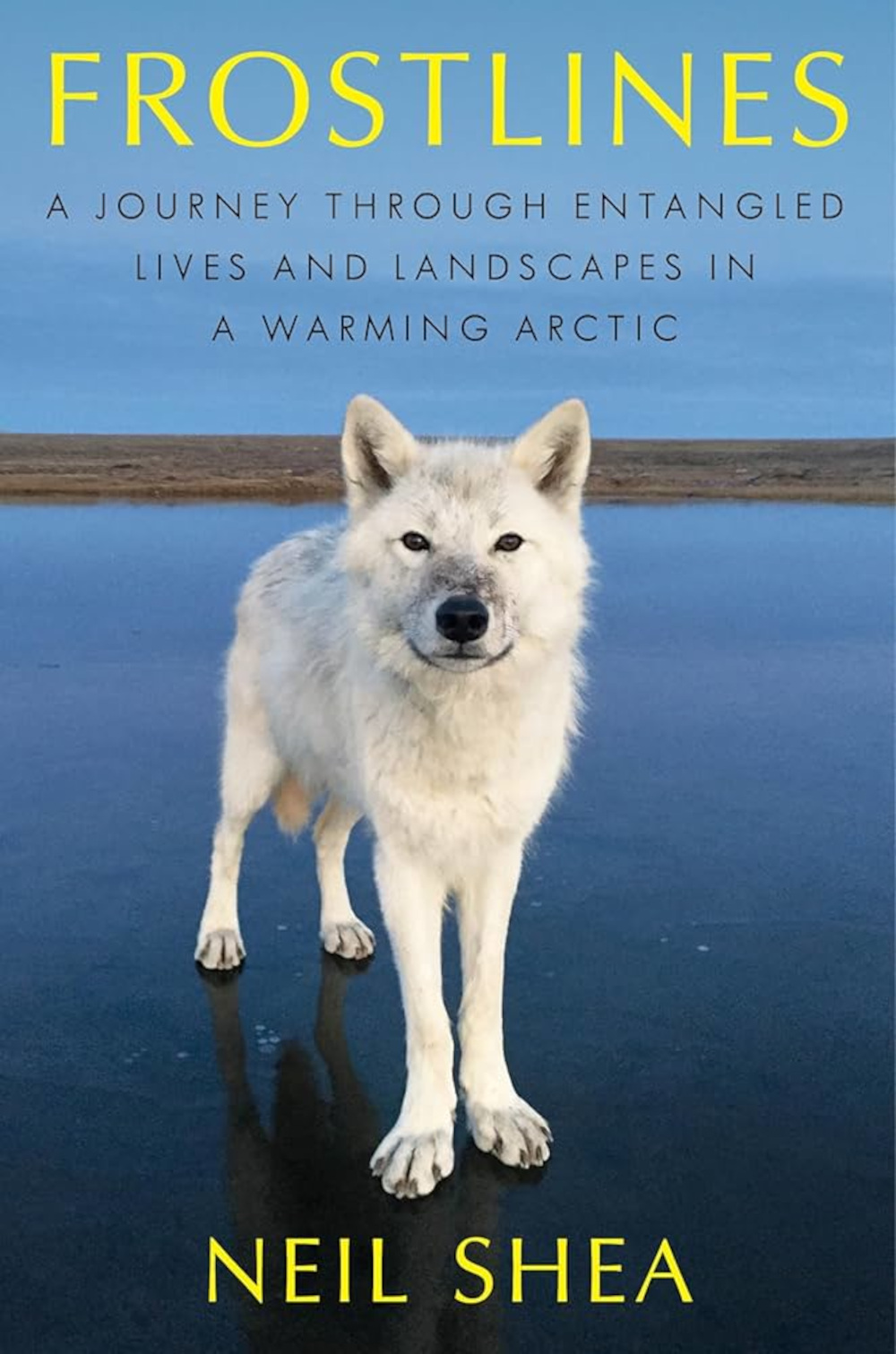

Neil Shea didn’t expect a wolf to invade his tent. It happened during a reporting trip on the Fosheim Peninsula in Nunavut, Canada, while Shea was chipping a hole in a pond for water. He looked up and saw his tent flapping maniacally in what looked like wind — but the air was calm. It turned out that a white wolf, part of a famous pack on Fosheim, had sliced his tent open. Shea watched as she pulled out all his possessions, laid them on the grass, grabbed his inflatable pillow, then bounded off over the Arctic plains, giddy as a dog with a chew toy.

Shea’s encounter with the pillow-stealing wolf is just one of the many arresting images and anecdotes in his new book, “Frostlines: A Journey Through Entangled Lives and Landscapes in a Warming Arctic.” Shea has spent 20 years as a reporter for National Geographic, a role that’s brought him time and time again to the circle of Earth that lies above roughly 66.5 degrees latitude. In this slim book’s six chapters, Shea recollects his most memorable encounters with Arctic people, animals, and nuna (an Indigenous word for land that carries many meanings), capturing the terror and beauty of a place that many people dismiss as “big, cold, white, and far away.” What emerges is an elegiac portrait of a region in flux, a land whose ice is melting, whose animals are dwindling, whose elders are dying — and whose fate is inextricably linked with ours.

BOOK REVIEW — “Frostlines: A Journey Through Entangled Lives and Landscapes in a Warming Arctic,” by Neil Shea (Ecco, 240 pages).

When readers imagine a changing Arctic, they’re likely thinking of climate change. One can imagine a version of “Frostlines” that hammers readers with abstract stakes and studies on ice melt, a version where Shea crammed southern concerns about warming into a narrative about the people and places of the north. A younger Shea might have written that book. When he first started reporting on the region, he writes, he would pepper his sources with questions, derived from his southern mindset, about warming and ice melt. But he had a wake-up call during an ice-fishing expedition with an Inuit patrol near the famed Northwest Passage. “One thing I learn quickly out here,” he writes, “is that when you are camped on the surface of a frozen lake, no one wants to talk about climate change.”

Over the years, Shea learned to “watch more, ask less,” a philosophy that serves this book immeasurably. He lets the stories he gathered speak for themselves, creating reader investment by immersing us in the sublime beauty and singular cultures of this place.

With Shea, we watch narwhals touching tusks in Admiralty Inlet. We visit Fosheim, home to a pack of white wolves like the one who stole Shea’s pillow, who in their isolation never learned to fear people. (These wolves are as likely to gather around humans “like students attending a lecture” as they are to fell a musk ox.) We hear about the time a bear chased Shea over sea ice in a blur, a memory that comes back to him in dreams conjuring the“blue of ice, black of the bear’s eyes, red vivid blood on his coat from a recent meal of seal.” We venture with him to an archaeological dig in Greenland, where Danish researchers search for answers about the fate of a lost Norse colony from the Middle Ages, and on a patrol with the Rangers, a volunteer arm of the Canadian army who keep watch on the tundra as the “eyes and ears in the north.”

Shea’s attention to detail and evocative prose do much to sweep the reader up in his experiences. He eats “boiled seal with ketchup” and rides a four-wheeler into “deep green sedge meadows filled, like shrines, with the bleached bones of musk oxen.” A fish resembles “the arch of a woman’s foot”; an outcropping of rocks, “a great hook-beaked gargoyle.”

But the Arctic is not just a series of beautiful landscapes. It’s also home to four million people, people for whom “cold is freedom.” In introducing us to the Arctic’s human inhabitants, Shea complicates and texturizes a place that many southerners mischaracterize or misunderstand. He exposes the “line of dissonance drawn between the white world, the world of science and politics, and the Indigenous one, which relied on other ways of seeing, assessing, and negotiating reality.”

In the American and Canadian Arctic, a region still under the long shadow of colonialism, many of Shea’s interviewees are less concerned about climate change than about the death of their elders and the resulting loss of traditions and knowledge. In Gjoa Haven, where Shea originally ventures to observe ice melting along the Northwest Passage, he meets Jacob, a hunter of animals like seals — and, some say, whales — who lives by the “old ways” and teaches his son his native language. A few years later, Jacob died of Covid complications. In Alaska, Shea visits a community concerned about the dwindling of a local caribou herd, where he watches an elder teach schoolchildren how to butcher these animals, not knowing that the man would suffer a heart attack and die the next day. Along with Shea, we witness the end of a way of life, in real time.

But Shea refuses to establish a simple binary between the beauty of tradition and the corrosiveness of modernity: He also showcases the difficulty of life in a region that outsiders consider an afterthought, where even basic amenities are lacking. In one passage, Martin, Jacob’s son and the commander of the Rangers, laments the lack of cellphone service in his town, telling Shea, “Kinda sucks that I can’t call a doctor when my kid’s sick.” Shea reminds him that there isn’t a doctor in town anyway. Through the lens of these voices emerges a complex Arctic, full of people grieving lost traditions while also chafing against southern governments that treat them as a last priority.

Shea initially wanted to circumnavigate the entire Arctic Circle, starting in Alaska and ending in Eastern Russia, but the war in Ukraine killed that plan. In his last chapter, Shea confronts this situation head-on by bringing us to Kirkenes, the Norwegian town situated on the border with Russia. There, he interviews journalists writing about their home country in exile, visits a bridge built by Nazis when they occupied the town during World War II, and meets Norwegian conscripts who spend their days watching Russia with telescopes. In this essay, Shea paints a portrait of an Arctic very different from the archaeological sites of Greenland and wolf packs of Canada. This is “the most violent Arctic I had seen, busy with real and imagined bloodshed,” he writes. These geopolitical tensions, including President Donald Trump’s increasingly aggressive moves to annex Greenland, foreshadow the Arctic as battleground, a region where great powers will jockey for control of priceless resources as the world warms.

Shea’s writing occasionally veers into an overpoetic register or into sentimentality, as in a passage where he speculates that the mayor of an Alaskan town is obsessed with preserving Indigenous knowledge as penance for previous crimes. Overall, though, “Frostlines” is an intricately observed, fully immersive piece of travel and science writing as well as a vividly compelling argument for why readers should care about this region.

The Arctic has a singular wildness, where you “see things that simply aren’t visible anywhere else,” he writes. If someone didn’t think this place was important before, they will after reading this book. And even though Shea focuses on the Arctic’s value in its own right, rather than its worth in relation to southern concerns, the fact remains that to care about the Arctic is to care about all of us. As Inuk activist Sheila Watt-Cloutier wrote, “What is happening today in the Arctic is the future of the rest of the world.”

The Pacific use to be pretty quite once and not much going on there. Then you have all these anti-China alliances and weapons to Taiwan coming about and now the Pacific is a flashpoint for a possible war between the US and China. I fear the same with the Arctic as it gets crowded with military forces, icebreakers, oil corporations, merchant vessels so that it too will become a possible flashpoint between the US and Russia/China. And the four million people living in this region? They will be pushed to the side and their way of life destroyed.