Yves here. Many commentators have described the sorry state of Venezuela’s oil industry and taken a stab estimating what it would take to turn that around. The near-universal view is that it would take many years of large-scale, sustained investment before any serious change in output was realized. This post usefully recaps that issue and then looks at the US refining side of the equation, identifying what it takes to process such heavy, nasty crude and the proportion of US refineries now able to handle that.

We are also reposting a particularly informative tweet that estimated the cost of a comprehensive upgrade of Venezuela’s oil production, including oft-neglected expenses to upgrade and greatly extend Venezuela’s grid. Note that the aim is to replace Canada’s heavy crude grades in the US, as in supply refiners set up to handle broadly similar feed stocks:

I have spent a lot of time talking shit at people with opinions on Venezuela’s oil production potential, and how it’s going to “RePLaCe CanADa”. So here’s my contribution — how I see the cost of replacing Canadian crude with Venezuelan heavy.

I think it’s a nearly $1 trillion… pic.twitter.com/XFlPVwPdew

— Michael Spyker (@ShaleTier7) January 4, 2026

By Alex Kimani, a veteran finance writer, investor, engineer and researcher for Safehaven.com. Originally published at OilPrice

- Trump’s push to lure U.S. oil majors back to Venezuela largely fell flat, with Exxon and ConocoPhillips calling the country uninvestable under current laws and citing past expropriations.

- Venezuelan crude is attractive to complex U.S. refiners with coking capacity, but only a subset of Gulf and East Coast plants can fully process the heavy, high-sulfur oil.

- Higher Venezuelan supply would displace Canadian, Mexican, and some Middle Eastern grades rather than broadly lift U.S. demand.

Last week, U.S. President Donald Trump’s Venezuela pitch to oil executives to invest the vast sums required to revive the country’s flagging oil sector proved largely ineffectual. Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM) CEO Darren Woods offered the starkest assessment, calling the South American country “uninvestable” under its current commercial frameworks and hydrocarbon laws, while ConocoPhillips (NYSE:COP) CEO Ryan Lance also gave Trump a reality check, informing him his company lost billions of dollars when it exited the country under the Chavez regime.

The serious descent of Venezuela’s energy sector into the abyss began after Hugo Chávez’s government nationalized the oil infrastructure and assets of ExxonMobil (NYSE:XOM) and ConocoPhillips (NYSE:COP) in 2007, after the companies refused to accept new terms that would give the Venezuelan state oil company, PDVSA, a majority share in their projects. The nationalization process was initiated in early 2007 through a presidential decree and a new Hydrocarbons Law.

Trump, however, scored some notable wins. To wit, Hilcorp‘s Jeff Hildebrand said his company is ready to go rebuild Venezuela’s energy infrastructure, while Chevron (NYSE:CVX) said it can ramp up its Venezuela production of 240K bbl/day “100% essentially effective immediately”.

Previously, we reported that it will take billions in infrastructure investments to return Venezuela’s oil sector to its 1970s peak production of 3.5 million barrels per day. Venezuela currently produces ~1 million barrels per day, with Chevron accounting for a quarter of that. U.S. refiners love Venezuelan crude because it provides a competitive advantage for complex refiners with substantial coking capacity that can process the heavy oil into high-value products. Merey crude from Venezuela’s Orinoco belt has among the lowest in API gravity and highest sulfur content globally, requiring specialized refinery units to break down the heaviest molecules and remove impurities.

Unfortunately, less than half of U.S. refineries have a coker, with refiners along the Gulf and East Coasts most likely to benefit from higher Venezuelan crude supplies. U.S. refiners with the highest coking capacity include Valero (NYSE:VLO), Exxon, Chevron, Marathon Petroleum(NYSE:MPC), Phillips 66 (NYSE:PSX) and PBF Energy (NYSE:PBF).

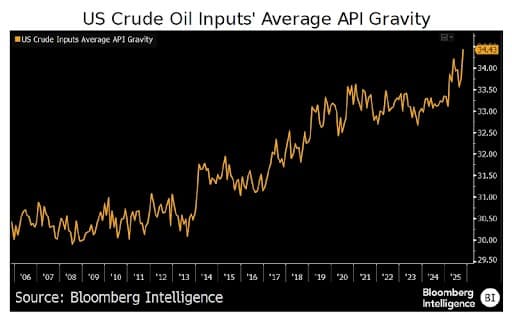

Coking and hydrocracking are petroleum refining processes that upgrade heavy crude oil fractions into lighter, more valuable products like gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel, but they use different methods: Coking is a thermal, carbon-rejection process, essentially baking heavy oil to leave solid petroleum coke and lighter liquids. Hydrocracking uses high-pressure hydrogen and a catalyst to chemically add hydrogen, breaking large molecules into smaller ones, producing cleaner fuels with fewer solid byproducts. Highly complex refiners can achieve distillate yields of 33% compared to 30% for medium-complexity plants. Shortages of heavy oils like Venezuelan crude have forced many U.S. refineries to invest in topping units to refine lighter oils such as U.S. shale oil.

Source: Bloomberg

Increased availability of Venezuelan crude is, however, likely to take a toll on demand for Canadian crude, Mexican Maya, and Middle Eastern grades. The U.S. still buys 80% of Canada’s crude output, despite the recent TMX expansion improving access to Asia. This helps to keep WCS (Western Canadian Select) prices tied to U.S. refinery demand and alternative heavy grades. On the other hand, more Venezuelan flows are likely to benefit Mid-continent and West Coast refiners, including British Petroleum (NYSE:BP) and HF Sinclair (NYSE:DINO), thanks to greater WCS discounts if Gulf Coast demand is displaced.

That said, Venezuela’s low-hanging fruit is rather limited: According to Norwegian energy consultancy Rystad Energy, only 300-350 kbpd can be quickly restored with minimal spending from the current clip of 800,000 bpd-1 million bpd, with production beyond 1.4 mbpd requiring heavy, sustained investment.

Rystad estimates that Venezuela will require $53 billion over the next 15 years just to keep production flat at 1.1 mbpd, but could need up to $183 billion over the same period to ramp up production to over 3 million bpd, roughly equivalent to the entire North American land capex for one year.

Analysts at satellite intelligence company Kayrros have described Venezuela’s energy infrastructure as being in a “catastrophic state” following decades of under-investment, disrepair, and cannibalization of equipment.

According to Kayrros, numerous oil storage tanks at the Bajo Grande and Puerto Miranda terminals are out of order due to corrosion and a lack of maintenance. But this is an industrywide problem: Kayrros estimates that roughly a third of Venezuela’s storage capacity is currently inactive, reflecting unusable storage tanks, reduced refinery operating rates, and declining oil production. Meanwhile, operations at the large interconnected Amuay and Cardón refineries are running below 20% of capacity, essentially turning them into “de facto storage centres” according to the experts.

Not surprisingly, Venezuela’s pipeline network is in a similar state of disrepair: A leaked document from PDVSA in 2021 revealed that the country’s oil pipelines had not been updated in 50 years, with Venezuela’s National Oil Company estimating it would take a staggering $58 billion to get them back in peak condition. Recent estimates have placed the figure in excess of $100 billion. Venezuela’s operational oil pipeline network has a total length of 2,139 miles (approximately 3,442 kilometers). For some perspective, the UAE, which produces approximately 3.2 million bpd, has ~9,000 km of oil pipeline.

If the Orange One 🍊 can increase military budget by $500 billion in a year, he can find 2/5th of that for these repairs? Greenland anyone? 🥶

We debunked in our companion post on Greenland the idea that seizing it would improve government finances. Any winnings will go to private cronies.

What winnings? Denmark is bleeding krones to keep Greendland a semi-functional autonomy (1/5 live below poverty line). I believe direct subsidies are about 40% of the annual budget, and the rest comes from exporting fish to Denmark and China.

those subsidies will be the first to go if they become Americans – The US is never going to do anything about its slums and lack of support for domestic infrastructure.

Sen Alan Grayson:

“The Republican healthcare plan amounts to “Don’t get sick” and, if you do, “Die quickly.”

https://www.cnn.com/2009/POLITICS/09/30/house.floor.controversy/

I already saw signs of protests at the importation of Venezuelan heavy crudes into the country as they would be in direct competition with American heavy crudes. If I remember correctly, these protests were in Texas and happened only a coupla days ago.

I seem to remember that the refining capacity of the U.S. is antiquated, weak and hadn’t had any capacity increase in many decades. Since we are running at near capacity, how would we deal with a flood of oil from Venezuela, other than to displace oil gotten from other sources? Getting feedstocks cheaper may increase profits for someone, but won’t increase total output.

According to EIA from 1985 capacity has gone from roughly 15.5 million bbl/day to 18 million. But I think utilization is tied to demand factors downstream? I think the main trend has been from the majors spinning off refining capacity to dedicated refining companies (Marathon, Valero, Phillips 66). It remains to be seen what happens to the PDV Holdings (CITGO) sale to PE.

Rubio just wants to demolish Cuba. The key question with Venezuela: How much of its ‘reserves’ are actually econmically to extract let alone get to market. All this is a resurrection of the Cold War: No left leaning states in the Western Hemisphere. In the event, when I was growing up during the last century, the US aspired to having a government representing the ‘people’. At present it is difficult to determine whether the Trump is based on aFacist model ,a Stalinesque,one or on just a plain old banana republic with lots of guns; and we the people’ seem to be happy with any one of the aforementioned.

[Replying to Anthony Martin]: I believe that you are totally right with your statement in the first sentence of your comment. The ultimate and most relevant target of this intervention in Venezuela is Cuba. That’s the prize that the USA has been wanting since at least John Quincy Adams, and that’s also the previous possession the US lost (after taking it away from Spain in 1898) with Castro’s revolution, and then with the immediate US hostility to him from the get go, and the subsequent alignment of Cuba with the Soviets during the Cold War. I think that the fact that Castro dared to point nuclear weapons at the US is the sin that has never been forgotten nor forgiven in Washington, and they figured the time was ripe (Cuba never had a worse government in charge since at least the 1960s, and Venezuela was already weak and diminished before Maduro’s abduction). Having a Cuban-American neocon at the helm of the State Department is certainly helpful, and not a coincidence.

This week, the Canadian Prime Minister is in China, and they are talking about petroleum exports. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/china-trade-mission-carney-9.7046150 “China looking for trading partners that ‘don’t use energy for coercion,’ Hodgson, says” (Tim Hodgson, Minister of Energy and Natural Resources) It will be interesting what happens when this development gets high enough on Trump’s to-do list. After all, Canada is in the Western Hemisphere.