By Steve Keen, Associate Professor of Economics & Finance at the University of Western Sydney and author of Debunking Economics: The Naked Emperor of the Social Sciences

The US Senate should not reappoint Ben Bernanke. As Obama’s reaction to the loss of Ted Kennedy’s old seat showed, real change in policy only occurs after political scalps have been taken. An economic scalp of this scale might finally shake America from the unsustainable path that reckless and feckless Federal Reserve behavior set it on over 20 years ago.

Some may think this would be an unfair outcome for Bernanke. It is not. There are solid economic reasons why Bernanke should pay the ultimate political price.

Haste is necessary, since Senator Reid’s proposal to hold a cloture vote could result in a decision as early as this Wednesday, and with only 51 votes being needed for his reappointment rather than 60 as at present. This document will therefore consider only the most fundamental reason not to reappoint him, and leave additional reasons for a later update.

Misunderstanding the Great Depression

Bernanke is popularly portrayed as an expert on the Great Depression—the person whose intimate knowledge of what went wrong in the 1930s saved us from a similar fate in 2009.

In fact, his ignorance of the factors that really caused the Great Depression is a major reason why the Global Financial Crisis occurred in the first place.

The best contemporary explanation of the Great Depression was given by the US economist Irving Fisher in his 1933 paper “The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions”. Fisher had previously been a cheerleader for the Stock Market bubble of the 1930s, and he is unfortunately famous for the prediction, mere days before the 1929 Crash:

Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau. I do not feel that there will soon, if ever, be a fifty or sixty point break below present levels, such as Mr. Babson has predicted. I expect to see the stock market a good deal higher than it is today within a few months. (Irving Fisher, New York Times, October 15 1929)

When events proved this prediction to be spectacularly wrong, Fisher to his credit tried to find an explanation. The analysis he developed completely inverted the economic model on which he had previously relied.

His pre-Great Depression model treated finance as just like any other market, with supply and demand setting an equilibrium price. However, in building his models, he made two assumptions to handle the fact that, unlike the market for say, apples, transactions in finance markets involved receiving something now (a loan) in return for payments made in the future. Fisher assumed

(A) The market must be cleared—and cleared with respect to every interval of time.

(B) The debts must be paid. (Fisher 1930, The Theory of Interest, p. 495)

I don’t need to point out how absurd those assumptions are, and how wrong they proved to be when the Great Depression hit—Fisher himself was one of the many whose fortunes were wiped out by margin calls they were unable to meet. After this experience, he realized that his previous assumption of equilibrium blinded him to the forces that led to the Great Depression. The real action in an economy occurs in disequilibrium:

We may tentatively assume that, ordinarily and within wide limits, all, or almost all, economic variables tend, in a general way, toward a stable equilibrium… But the exact equilibrium thus sought is seldom reached and never long maintained. New disturbances are, humanly speaking, sure to occur, so that, in actual fact, any variable is almost always above or below the ideal equilibrium…

It is as absurd to assume that, for any long period of time, the variables in the economic organization, or any part of them, will “stay put,” in perfect equilibrium, as to assume that the Atlantic Ocean can ever be without a wave. (Fisher 1933, p. 339)

A disequilibrium-based analysis was therefore needed, and that is what Fisher provided. He had to identify the key variables whose disequilibrium levels led to a Depression, and here he argued that the two key factors were “over-indebtedness to start with and deflation following soon after”. He ruled out other factors—such as mere overconfidence—in a very poignant passage, given what ultimately happened to his own highly leveraged personal financial position:

I fancy that over-confidence seldom does any great harm except when, as, and if, it beguiles its victims into debt. (p. 341)

Fisher then argued that a starting position of over-indebtedness and low inflation in the 1920s led to a chain reaction that caused the Great Depression:

(1) Debt liquidation leads to distress selling and to

(2) Contraction of deposit currency, as bank loans are paid off, and to a slowing down of velocity of circulation. This contraction of deposits and of their velocity, precipitated by distress selling, causes

(3) A fall in the level of prices, in other words, a swelling of the dollar. Assuming, as above stated, that this fall of prices is not interfered with by reflation or otherwise, there must be

(4) A still greater fall in the net worths of business, precipitating bankruptcies and

(5) A like fall in profits, which in a “capitalistic,” that is, a private-profit society, leads the concerns which are running at a loss to make

(6) A reduction in output, in trade and in employment of labor. These losses, bankruptcies, and unemployment, lead to

(7) Pessimism and loss of confidence, which in turn lead to

(8) Hoarding and slowing down still more the velocity of circulation. The above eight changes cause

(9) Complicated disturbances in the rates of interest, in particular, a fall in the nominal, or money, rates and a rise in the real, or commodity, rates of interest. (p. 342)

Fisher confidently and sensibly concluded that “Evidently debt and deflation go far toward explaining a great mass of phenomena in a very simple logical way”.

So what did Ben Bernanke, the alleged modern expert on the Great Depression, make of Fisher’s argument? In a nutshell, he barely even considered it.

Bernanke is a leading member of the “neoclassical” school of economic thought that dominates the academic economics profession, and that school continued Fisher’s pre-Great Depression tradition of analysing the economy as if it is always in equilibrium.

With his neoclassical orientation, Bernanke completely ignored Fisher’s insistence that an equilibrium-oriented analysis was completely useless for analysing the economy. His summary of Fisher’s theory (in his Essays on the Great Depression) is a barely recognisable parody of Fisher’s clear arguments above:

Fisher envisioned a dynamic process in which falling asset and commodity prices created pressure on nominal debtors, forcing them into distress sales of assets, which in turn led to further price declines and financial difficulties. His diagnosis led him to urge President Roosevelt to subordinate exchange-rate considerations to the need for reflation, advice that (ultimately) FDR followed. (Bernanke 2000, Essays on the Great Depression, p. 24)

This “summary” begins with falling prices, not with excessive debt, and though he uses the word “dynamic”, any idea of a disequilibrium process is lost. His very next paragraph explains why. The neoclassical school ignored Fisher’s disequilibrium foundations, and instead considered debt-deflation in an equilibrium framework in which Fisher’s analysis made no sense:

Fisher’ s idea was less influential in academic circles, though, because of the counterargument that debt-deflation represented no more than a redistribution from one group (debtors) to another (creditors). Absent implausibly large differences in marginal spending propensities among the groups, it was suggested, pure redistributions should have no significant macroeconomic effects. (p. 24)

If the world were in equilibrium, with debtors carrying the equilibrium level of debt, all markets clearing, and all debts being repaid, this neoclassical conclusion would be true. But in the real world, when debtors have taken on excessive debt, where the market doesn’t clear as it falls, and where numerous debtors default, a debt-deflation isn’t merely “a redistribution from one group (debtors) to another (creditors)”, but a huge shock to aggregate demand.

Crucially, even though Bernanke notes at the beginning of his book that “the premise of this essay is that declines in aggregate demand were the dominant factor in the onset of the Depression” (p. ix), his equilibrium perspective made it impossible for him to see the obvious cause of the decline: the change from rising debt boosting aggregate demand to falling debt reducing it.

In equilibrium, aggregate demand equals aggregate supply (GDP), and deflation simply transfers some demand from debtors to creditors (since the real rate of interest is higher when prices are falling). But in disequilibrium, aggregate demand is the sum of GDP plus the change in debt. Rising debt thus augments demand during a boom; but falling debt substracts from it during a slump.

In the 1920s, private debt reached unprecedented levels, and this rising debt was a large part of the apparent prosperity of the Roaring Twenties: debt was the fuel that made the Stock Market soar. But when the Stock Market Crash hit, debt reduction took the place of debt expansion, and reduction in debt was the source of the fall in aggregate demand that caused the Great Depression.

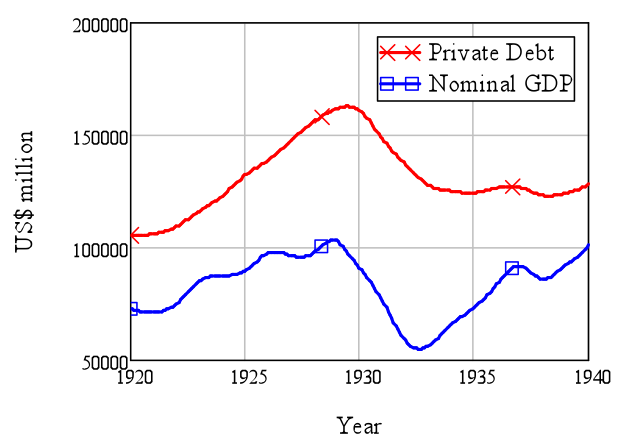

Figure 1 shows the scale of debt during the 1920s and 1930s, versus the level of nominal GDP.

Figure 1: Debt and GDP 1920-1940

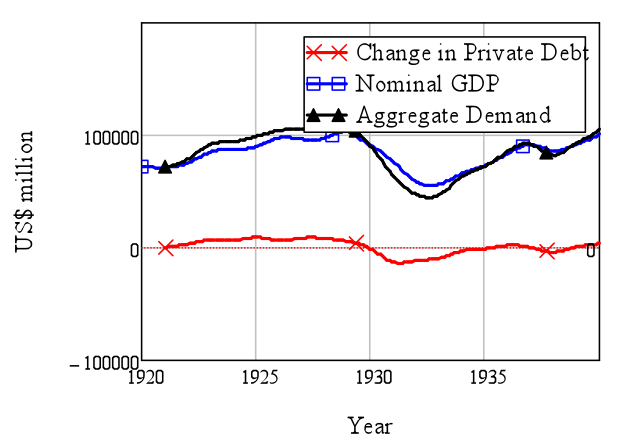

Figure 2 shows the annual change in private debt and GDP, and aggregate demand (which is the sum of the two). Note how much higher aggregate demand was than GDP during the late 1920s, and how aggregate demand fell well below GDP during the worst years of the Great Depression.

Figure 2: Change in Debt and Aggregate Demand 1920-1940

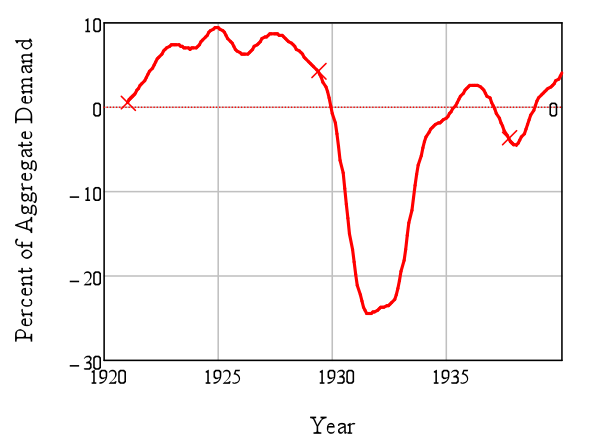

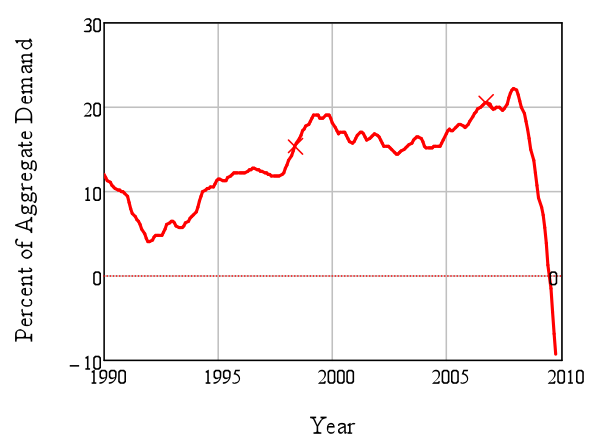

Figure 3 shows how much the change in debt contributed to aggregate demand—which I define as GDP plus the change in debt (the formula behind this graph is “The Change in Debt, divided by the Sum of GDP plus the Change in Debt”).

Figure 3: Debt contribution to Aggregate Demand 1920-1940

So during the 1920s boom, the change in debt was responsible for up to 10 percent of aggregate demand in the 1920s. But when deleveraging began, the change in debt reduced aggregate demand by up to 25 percent. That was the real cause of the Great Depression.

That is not a chart that you will find anywhere in Bernanke’s Essays on the Great Depression. The real cause of the Great Depression lay outside his view, because with his neoclassical eyes, he couldn’t even see the role that debt plays in the real world.

Bernanke’s failure

If this were just about the interpretation of history, then it would be no big deal. But because they ignored the obvious role of debt in causing the Great Depression, neoclassical economists have stood by while debt has risen to far higher levels than even during the Roaring Twenties.

Worse still, Bernanke and his predecessor Alan Greenspan operated as virtual cheerleaders for rising debt levels, justifying every new debt instrument that the finance sector invented, and every new target for lending that it identified, as improving the functioning of markets and democratizing access to credit.

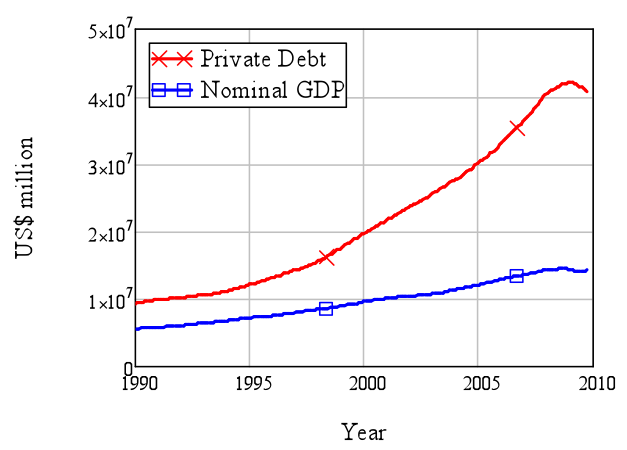

The next three charts show what that dereliction of regulatory duty has led to. Firstly, the level of debt has once again risen to levels far above that of GDP (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Debt and GDP 1990-2010

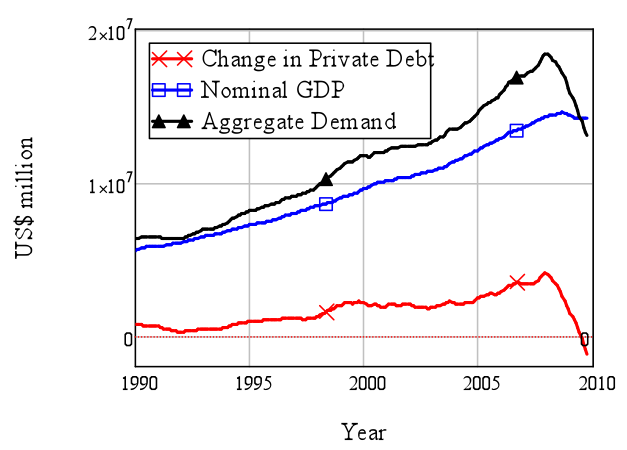

Secondly the annual change in debt contributed far more to demand during the 1990s and early 2000s than it ever had during the Roaring Twenties. Demand was running well above GDP ever since the early 1990s (Figure 5). The annual increase in debt accounted for 20 percent or more of aggregate demand on various occasions in the last 15 years, twice as much as it had ever contributed during the Roaring Twenties.

Figure 5: Change in Debt and Aggregate Demand 1990-2010

Thirdly, now that the debt party is over, the attempt by the private sector to reduce its gearing has taken a huge slice out of aggregate demand. The reduction in aggregate demand to date hasn’t reached the levels we experienced in the Great Depression—a mere 10% reduction, versus the over 20 percent reduction during the dark days of 1931-33. But since debt today is so much larger (relative to GDP) than it was at the start of the Great Depression, the dangers are either that the fall in demand could be steeper, or that the decline could be much more drawn out than in the 1930s.

Figure 6: Debt contribution to Aggregate Demand 1990-2010

Conclusion

Bernanke, as the neoclassical economist most responsible for burying Fisher’s accurate explanation of why the Great Depression occurred, is therefore an eminently suitable target for the political sacrifice that America today desperately needs. His extreme actions once the crisis hit have helped reduce the immediate impact of the crisis, but without the ignorance he helped spread about the real cause of the Great Depression, there would not have been a crisis in the first place. As I will also document in an update in early February, some of his advice has made America’s recovery less effective than it could have been.

Obama came to office promising change you can believe in. If the Senate votes against Bernanke’s reappointment, that change might finally start to arrive.

Professor Steve Keen

www.debtdeflation.com/blogs

Can we contact Australian PM Kevin Rudd? I mean, just to “borrow” Steve Keen for Fed Chairman? He wouldn’t be beholden to any special interest group, and could certainly shake up a thing or two around here.

After all, soccer teams of great fame hire foreign coaches, no?

:-D

This whole emphasis on the distinction between an economics of equilibrium vs an economics of disequilibrium strikes me as logically unfounded. After all, what drives the whole debt deflation scenario described above, what drives even the concept of it, other than the idea that an equilibrium has not yet been found. And it is hardly the case that that imbalances and forced liquidation occur only within financial products. Commodity producers or apparel manufacturers can overestimate demand for x or y product and be compelled, even in the absence of debt, (albeit only by rational expectations) to cut prices. And this put pressure on all competitors in the same field. C’mon man!

http://www.google.com/search?q=c%27mon+man&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&aq=t&rls=org.mozilla:en-US:official&client=firefox-a

you’re just describing the “normal” business cycle of typical capitalist overproduction and market adjustment. think that’s what’s going on?

Steve Keen actually got through a post without claiming that he is one of the 12 people in the world who predicted the global financial crisis.

Funny how he did that when he still doesn’t know what a CDO is.

Pot. Kettle.

@anon

Sup, Ben. Lots of luck with that confirmation.

:)

Professor Keen has a very cogent point. This Great Recession has many motivators, many of which have their origin in events that occured a generation ago. This Great Recession is not about excess inventory. This Great Recession is about about money.

There is the currency and then there is Credit Money. It is our Credit Money that has gone walk about. It is our acceptance of the perfidious devaluation in purchasing power of our money that sets the stage for excessive use of Credit Money. Deleveraging is necessary to rebalance the claims on the production of goods and services.

That means that the great economic adjustment we are experiencing will entail a great deal of pain. Quite simply too much Credit Money has been created and it must now be destroyed. The party is over, or if we are as resourceful as we think, it should be directly addressed.

Enterprises that should have failed and been liquidated are still with us. It’s time to jump out of the squirrel cage and repudiate all that debt that cannot be serviced. It’s time to prosecute fraud. We need a Fed Chairman who genuinely understands that the Great Depression was about the collapse of a great credit bubble. This Great Recession is about a very similar circumstance.

What finally proved to be basis for a sustainable recovery was the anticipation of and entry into WWII. In that event we imposed forced savings and postwar it was those savings that fueled the recovery of total demand. Beginning in the 60s we began to rely on credit for the expansion of aggregate demand.

At every turn, since its inception, the Fed has relied on distorting efforts to motivate aggregate demand by way of interest rates. Over the years our fractional reserve banking system has been made into a virtual ponzi scheme. At every turn the Fed has facilitated the erossion of purchasing power.

Why is there such fear of deflation? If you restore the currency to being a legitimate store of value, why can that be a bad thing? When the currency is a legitimate store of value saving is enhanced. On the other hand when the general expectation is that the currency will buy more today than it will tomorrow, what is the rational choice? Buy now or buy later?

That is what is at the core of this crisis. I have heard nothing about restoring the purchasing power of the currency.

Professor Keen is a voice to be heeded.

Steve Keen cross-posted on Yves Smith site? This is like Wonder Woman visits the Bat Cave. Not sure about their ability to leap tall buildings or anything, but when it comes to debunking financial nonsense, they’re a Dynamic Duo.

“Fisher envisioned a dynamic process in which falling asset and commodity prices created pressure on nominal debtors…”

What is a “nominal” debtor?

Looks like the WSJ “Review & Outlook” page endorses a change at the FED:

“We agree that the Fed needed to ease money precipitously when the financial markets suffered their heart attack in late 2008, and we praised Mr. Bernanke for that at the time and since. But the issue for the next four years is whether the Fed can extricate itself from its historic interventions before it creates a new round of boom and bust. We already see signs that it has waited too long to move.

The Fed as an institution is also under political attack in a way that it hasn’t been since the early 1980s, and that was when Paul Volcker was being excoriated for being too tight. That criticism has rarely if ever been leveled at Mr. Bernanke. The next Fed chairman is going to need the market credibility, and the political support, to raise interest rates when much of Congress and Wall Street will be telling him to stay at zero. That is the real reason to oppose a second term for Chairman Bernanke.”

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704562504575021704013095196.html?mod=WSJ_article_MoreIn

Net debt was lower in 1939 than it was 10 years earlier in 1929. Your thesis has merit.

But “when Paul Volcker was being excoriated for being too tight” Ludicrous. From the start of the DIDMCA Volcker let total reserves increase at a 17% annual rate of change (until DEC). Volker targeted non-borrowed reserves when at times 10% + of all reserves were borrowed (we just went thru a period of high borrowed reserves). Then Volcker widened the federal funds bracket racket (he didn’t eliminate it). Volcker then set off the “time bomb” where NOW accounts were introduced nation wide. This propelled the transactions velocity of money to extreme levels (and resulted in a major shift by account holders, into new deposit classifications) culminating in a 19.2% nominal gdp the 1st qtr of 1981. Volcker was the worst ever, not Bernanke.

Flow5,

Volcker WAS excoriated for his tight monetary policies. Where were you in 1980? Short term rates went to 22%. You could not sell a corporate bond in 1981 for under 14%. Banks were still restricted to 19% on their credit card portfolios, so they were hemorrhaging money. Volcker pushed the economy into a very steep recession, and had to back off because the feedback loop via the banks was intensifying the sovereign debt crisis. Many observers, even in retrospect, think Volcker came close to pushing the economy into a full blown depression (as in he was on the verge of precipitating bank failures).

Sounds just like the “Mellon Prescription” that the economy sorely needed then, as now. Purge the rottenness at the core. Why is it that this inexorable conclusion is summarily ignored by TPTB?

Irving Fisher was a signatory of the Chicago Plan of 1933. That plan advocated Quantitative Easing plus a Reinforcing Stimulus ( Govt Borrowing ). It seems to me that’s what we have and what Bernanke advocates. The disagreements are about the size, composition, and timing of the QE & Stimulus. I disagree with his mix as well, but I don’t think you can so easily say that he’s not following Fisher.

As for the cause of the crisis and how to prevent it, his book “100% Money” addresses that. The paper on Debt-Deflation is more focused on how to get out of it once you’re in it. Of course, that answer is Reflation, which produced by QE and a Reinforcing Stimulus. Here’s what he says about Over-Indebtedness:

“The over-indebtedness hitherto presupposed must have had its starters. Over-indebtedness may be started by many causes, of which the most common appears to be new opportunities to invest at a big prospective profit, as compared with ordinary profits and interest. Such new opportunities occur through new inventions, new industries, development of new resources, opening of new lands or new markets. When the rate of profit is expected to be far greater than the rate of interest, we have the chief cause of over-borrowing. When an investor thinks he can make over 100 per cent per annum by borrowing at 6 per cent, he will be tempted to borrow, and to invest or speculate with borrowed money. This was a prime cause leading to the over-indebtedness of 1929. Inventions and technological improvements created wonderful investment opportunities, and so caused big debts….

When the starter consists of new opportunities to make unusually profitable investments, the bubble of debt, especially bank loans, tends to be blown bigger and faster than when the starter is some great misfortune, like an earthquake causing merely non-productive debts….

The public psychology of going into debt for gain passes through at least four more or less distinct phases: (a) the lure of big prospective profits in the form of dividends, i.e. income in the future; (b) the hope of selling at a profit, and realizing a capital gain in the immediate future; (c) the vogue of reckless promotions, taking advantage of the habituation of the public to great expectations; (d) the development of downright fraud, imposing on a public which had grown credulous and gullible.

When it is too late, the dupes discover scandals like the Hatry and Kreuger scandals. At least one book has been written to prove that crises are due to frauds of clever promoters. But these frauds could seldom, if ever, have become so great without the original starters of genuine opportunities to invest lucratively. There is probably always a very real basis for the “new era” psychology before it runs away with its victims.

—100% Money, 130–32 (original emphasis)”

I’m trying to get people to recognize the importance of 4. Nevertheless, his list of causes is much more detailed than Bernanke and the Fed alone could have caused.

By the way, I advocate his main plans:

1) QE + Reinforcing Stimulus

2) Negative Interest Rates

3) Narrow/Limited/Utility Banking.

In reading the Chicago Plan proposal, as laid out in the Appendix to Dr. Ronnie Phillips’ book on The Chicago Plan and New Deal Banking Reform (pp190-199), I don’t see any reference to the QE of today nor any government stimulus borrowing.

The Chicago Plan first has general recommendations:

a.) That further decline in the volume of effective circulating media be prevented, prefereably by some sort of federal guarantee of bank deposits,

b.) That guarantee of bank deposits be undertaken only as part of a drastic program of banking reform which will certainly and permanently prevent any possible recurrence of the present banking crisis,

c.) That the administartion announce and pursue a policy of bringing about and maintaining a moderate increase in the level of wholesale prices, pending later adoption of some explicit criteria for long-run currency management.

In expanding on these general recommendations, the only call I can see for any government backing of loans were to provide for these broad depositor guarantees, especially over to the non-Fed banks, and as necessary to reflate wholesale prices.

Given that the whole idea behind the Chicago Plan was to get the bankers out of the money-creation business and restore stability to the monetary system and the currency, I see very little in common with what Bernanke is proposing, although his zero percent lending is preventing prices from moving up. His actions are certainly as far as we can get from part b.) above.

Glad that we’re talking about the Chicago Plan on NC.

Thanks.

Joebhead,

I’m glad that you’re reading that book. See pages 196-197. I think that you’ll find QE and more Borrowing advocated there. Of course, they refer to price levels and federal emergency expenditures. Heuristically, it’s the same thing. But there is room for lots of debate as to the size, timing, and manner, of QE and Borrowing. Indeed, I differ from Bernanke. But he’s still following the heuristic or general framework of Fisher as far as I can tell on Reflation, which is Fisher’s way of getting out of Debt-Deflation.

On the other hand, you’re correct about the fact that Bernanke doesn’t agree with the Chicago Plan of 1933 as to what the structure of the financial system should look like. I just don’t know how probable it is that anyone advocating Narrow Banking could be picked as Fed Chairman. I’m for it. In fact, Laurence Kotlikoff has a new book on Limited Banking coming out in February.

Finally, here’s Milton Friedman, who was actually there:

From Milton Friedman (1972), “Comments on the Critics of ‘Milton Friedman’s Monetary Framework'”:

“The intellectual climate at Chicago had been wholly different. My teachers… blamed the monetary and fiscal authorities for permitting banks to fail and the quantity of deposits to decline. Far from preaching the need to let deflation and bankruptcy run their course, they issued repeated pronunciamentos calling for governmental action to stem the deflation-as J. Rennie Davis put it, “Frank H. Knight, Henry Simons, Jacob Viner, and their Chicago colleagues argued throughout the early 1930’s for the use of large and continuous deficit budgets ( NB Borrowing/Stimulus- Don ) to combat the mass unemployment and deflation of the times” (Davis 1968, p. 476). They recommended also “that the Federal Reserve banks systematically pursue open-market operations with the double aim of facilitating necessary government financing aind increasing the liquidity of the banking structure ( NB QE- Don )” (Wright 1932, p. 162)…. Keynes had nothing to offer those of us who had sat at the feet of Simons, Mints, Knight, and Viner.”

Take care,

Don

PS Sorry I just came across your comment

Bernanke is going to be shoved down our throats whether we like it or not.

Any attempt at reform will be scuttled by the national house of ill repute(NHIR)- Congress.

As our fearless leader, Yves Smith, has pointed out, Obama’s modus operandi is bait and switch. Watch the State of the Union Address. That will be the bait.

Burn it into your brain, because as events unfold you will be able to detect the switch.

Bait: “I will not rest until everyone who wants a job has one.”

Later: “I fully endorse the legislation before Congress, the full employment act of 2010.”

Switch: As the legislation is about to come for a vote, a GAO report will certify that it will cost trillions of dollars and it’s cost is unsustainable. A flurry of amendments will be passed in committee, which gut the bill and no new jobs will be created.

It is great showmanship. Obama deserves an academy award. Oh, wait a minute, he just received the political equivalent, the Nobel Peace prize.

I wrote something on this a couple of days ago. How Bernanke saw and misunderstood the Great Depression has everything to do with how he did not see or discounted the run up to the meltdown and how he responded to it, and why that response ultimately was wrong.

This is a great piece by Keen. I would just add the role of fraud and excess speculation in exacerbating debt by creating conditions in which it must increase exponentially. Bernanke never saw this or worse thought it was unimportant. Like Greenspan, he thought markets would self-correct and punish any excessive risk takers. But on the upside of a bubble excessive risk takers aren’t punished. They’re rewarded. Greenspan’s easy money policies which Bernanke supported just increased the size of the problem, indeed fueled it. But this does explain why Bernanke in his response to the meltdown wasn’t interested in punishing anyone or any institution. Fraud and excess were not significant factors to him. It also explains why Bernanke did so little between August 9, 2007 when the housing bubble burst and September 15, 2008 when the meltdown occurred. He was allowing markets to correct on their own with only minimal intervention by the Fed, mostly in the form of interest rate cuts.

My understanding of Bernanke’s take on the Great Depression is that he saw it as resulting from the failure of the Fed to ease/increase the monetary supply. As both the GD and our current crisis show, it is not the quantity of money but its velocity which is important. And when I say this I mean quantity alone is insufficient. It must also be directed away from unproductive and wealth destroying sectors into productive ones.

What Bernanke did was both incredibly wasteful and temporary. He dumped trillions into a broken system without fixing it. Yes, he prevented its immediate collapse but most of that debt is still floating out there in the form of misvaluations and temporary government backed loan vehicles. Now normally this would lead to Japanification: “the decline could be much more drawn out than in the 1930s” as Keen says. But this leaves out the fact that the system was never fixed. The stupid, greedy, and criminal were never punished. So the engines of disequilibrium which produced the 2008 meltdown are still in place and running. This makes Keen’s first possibility: “fall in demand could be steeper,” i.e. depression more likely.

‘Can we contact Australian PM Kevin Rudd? I mean, just to “borrow” Steve Keen for Fed Chairman?’

I’m not sure Rudd would even know who Steve Keen is. Keen is still a voice in the wilderness here in Australia, despite his now internationally recognised prescience, not to mention good sense. He gets the odd media gig but generally he blogs and gives lectures under the radar, obscured in the MSM by green shoots. He has for years been critical of the mainstream of Australian economics, and as a result has not been welcomed into it. He’s teaching at a suburban University while the profession’s top academic jobs are filled by neo’s. The Reserve Bank ignores him.

‘Steve Keen cross-posted on Yves Smith site? This is like Wonder Woman visits the Bat Cave. Not sure about their ability to leap tall buildings or anything, but when it comes to debunking financial nonsense, they’re a Dynamic Duo.’

It has been gratifying in the last 18 months or so to see all these disparate voices of reason coalescing into an informed opposition. I first saw Keen on TV in Sept 08 being interviewed alongside Peter Schiff and bookmarked the blogs of both men. I had been reading James Howard Kunstler and thru him people like Dmitri Orlov, Doug Noland at Prudent Bear, Stephen Roach and John Hussman, so I was already expecting Bad Things. Before long they were joined by Yves (this blog now tends to get visited first) Mish Shedlock, Karl Denninger, Michael Hudson, Dean Baker, Max Keiser, Janet Tavakoli, etc etc.

It’s great to see how often their ideas now cross-pollinate and how people from poles hitherto quite hostile to each other at times have joined forces, their differences burned away under the intense heat of this crisis. An aristocracy of common sense is taking shape outside of the academy.

‘Can we contact Australian PM Kevin Rudd? I mean, just to “borrow” Steve Keen for Fed Chairman?’

Yeah if its a swap, seems they would like been to blow bubbles down under. Can’t wait for the Australian government vis a vi citizen back stop trillions in crap ha ha.

Skippy…thanks as aways Mr. Keen BTW do you have enough computational power, I could help with lifting it.

Steve, I understand why a Coolige/Hoover-style free marketeer would assume that markets clear, but whence the assumption that debts always get paid, given that the idea that unfit competitors go into bankruptcy is a plank of Social Darwinism? Surely, nobody labored under the illusion that debts never exceed recoverable values. What am I missing here?

Yves Smith: If you mean that Volcker screwed up your right. Otherwise you clearly don’t understand what Volcker & company did.

I’ve never had a losing trade in interest rate futures (since July 1979). My prediction for AAA bonds was only off by 1 basis point in Sep 81. I doubt anyone on this planet was even close. Ask Jim Sinclair.

On October 6, 1979 Paul Volcker, Chairman, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve e System promised that the Fed was going to mend its ways. Hereafter the Fed would deemphasize the control of the federal funds rate and concentrate on holding the monetary aggregates in check. We were advised to “watch the money supply”.

For approximately the first four months following this pronouncement the money supply increased at an annualized rate of 20 percent… Up from the 8 percent increase in the prior five months… Obviously there had been no significant change in monetary policy. Why? Apparently the Manager of the Open Market Account who operated from an office in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and who is in charge of all open market purchases and sales for all 12 Federal Reserve banks decided there should be no change in monetary policy. Note: the actual monetary policy of the Fed during the 1980 was only nebulously related to the official policies of the Federal Open market committee (FOMC) as published in the Federal Reserve Bulletin. Open market purchases were of such a magnitude in this period member bank legal reserves expanded at an annualized rate of 20 percent. The excessive increase in the money supply made possible by this growth in reserves was accompanied by a continuing rise in the transactions velocity (rate of turnover) of money at an annualized rate of 24.9 percent. Consequently monetary flows (aggregate monetary purchasing power) shot up to annual rate of 33.3 percent –an excessively easy money policy in view of the virtual stagnation of real GDP growth during this period.

During the next 3 months or to the end of April 1980 the fed slammed on the brakes. Member bank legal reserves decreased at an annualized rate of 20 percent, and money flows declined at an annual rate of 16.8 percent as a consequence of a small drop in transactions velocity. Unfortunately the Fed reversed its tight money policy toward the end of April, and went on a monetary binge. For the six month period ending in December, member bank legal reserves were inflated at a 17 percent annualized rate, and the money supply expanded at an annualized rate of 20 percent and monetary flows (MVt) surged at an estimated annual rate of 29 percent.

Government and Federal Reserve economists contend it is impossible to control both interest rates and money, and that the shift to a monetarist policy from October 1979 – 1980 was the root cause of the excessively high and volatile interest rates that have prevailed over the past year. The fact is the Fed HAS NEVER TRIED A MONETARIST POLICY EXCEPT FOR THE THREE MONTHS ENDING IN APRIL 1980. Monetarism is more than watching the aggregates – it also involves controlling them properly. The Fed cannot control interest rates even in the short end of the market except temporarily. And by attempting to slow the rise in the federal funds rate the Fed will pump an excessive volume of legal reserves into the member banks. This, as noted, will fuel a multiple expansion in the money supply, increase monetary flows and generate higher rates of inflation – and higher interest rates including federal funds rates.

An even greater impediment to achieving the monetarist goals involves acquiring a technical staff for Congress as well as the Fed which does not confuse the supply of money with the supply of loan-funds; people who can make the proper distinctions between means-of-payment money and liquid assets; know the difference between money creating institutions and financial intermediaries; recognize aggregate monetary demand is measured by the flow of money –not nominal GDP; recognize that interest rates are the price of loan-funds. not the price of money; that the price of money is represented by the price level, that inflation is the most important factor determining interest rates operating as it does through both the demand for and the supply of loan-funds; and above all else recognize that even a temporary pegging of a series of federal funds rates over time forces the Fed to abdicate its power to regulate properly the money supply.

What is to be learned from Volcker’s dismal record of monetary mismanagement? Sandwiched between two excessively easy money periods of nine and six months was a period of tight money of less than three months. Yet in that short time the month-to-month rate of inflation of 18% that prevailed in the first quarter of 1980 (as measured by the CPI) was brought down to a rate of zero in July. With a short lag, interest rates also plummeted. Treasury bills which had been around 15.5% in Mar. 1980 were down to 6.4% in Jun. 1980; the Fed Funds rate which approached 20% in Apr. 1980 was down to less than 9% in Jul. 1980. Even long-term rates responded. From a 13% level in Mar. 1980 corporate AAA rates on bonds were down to around a 10.5% level in Jun. 1980. Mortgage rates experienced a similar decline. Responding to the decline in interest rates, the earlier decline in housing starts was turned around, and there were gains in other sectors of the economy. Even the rate of unemployment which had risen from less than 6% to about 7.5% began to fall.

In 1980, Paul Volcker, Past chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, appeared before the House Domestic Monetary Policy Subcommittee. In response to a question as to why the Fed had supplied an excessive volume of legal reserves to the member banks in the third quarter 1980 (annual rate of increase 13.2%), Volcker’s defense was that there are two types of legal reserves: 1) borrowed (reserves obtained by the banks through the Federal Reserve Bank discount windows), and 2) non-borrowed (reserves supplied the banking system consequent to open market purchases). He advised the congressmen to watch the non-borrowed reserves — “Watch what we do on our own initiative.” The Chairman further added — “Relatively large borrowing (by the banks from the Fed) exerts a lot of restraint.”

This is of course, economic nonsense. One dollar of borrowed reserves provides the same legal-economic base for the expansion of money as one dollar of non-borrowed reserves. The fact that advances had to be repaid in 15 days was immaterial. A new advance can be obtained, or the borrowing bank replaced by other borrowing banks. The importance of controlling borrowed reserves was indicated by the fact that at times nearly 10% of all legal reserves were borrowed.