As we described in earlier posts in this series (Executive Summary and Part II), OCC/Federal Reserve foreclosure reviews meant to provide compensation to abused homeowners were abruptly shut down at the beginning of January as the result of a settlement with ten major servicers. Whistleblowers from the biggest, Bank of America, provide compelling evidence that the bank and its independent consultant, Promontory Financial Group, went to considerable lengths to suppress any findings of harm to homeowners.

These whistleblowers, who reviewed over 1600 files and tested hundreds more in the attenuated start up period, saw abundant evidence of serious damage to borrowers. Their estimates vary because they performed different tests and thus focused on different records and issues. When asked to estimate the percentage of harm and serious harm they found, the lowest estimate of harm was 30% and the majority estimated harm at or over 90%. Their estimates of serious harm ranged from 10% to 80%.

We found four basic problems:

The reviews showed that Bank of America engaged in certain types of abuses systematically

The review process itself lacked integrity due to Promontory delegating most of its work to Bank of America, and that work in turn depended on records that were often incomplete and unreliable. Chaotic implementation of the project itself only made a bad situation worse

Bank of America strove to suppress and minimize evidence of damage to borrowers

Promontory had multiple conflicts of interest and little to no relevant expertise

We discuss the second major finding below.

Past whistleblower leaks from Bank of America and other reviews have pointed out how frequent changes to the review process, both from the OCC and from the independent reviewers, made the process disorderly. This confusion is likely to serve as a convenient excuse for why the costs of the reviews exploded, which was one of the two major rationales for shutting them down.

At Bank of America, the disorderliness of the project is only part of the story. Focusing on that aspect serves to exculpate OCC, the bank and Promontory. The dirty secret of these reviews is they could never have been done properly. There was no pre-existing, internally consistent, complete and provably correct account of a customer and his loan in the Bank of America systems. All the dysfunction of the reviews was inevitable given the state of the records. The only course of action possible was a cover-up; the only open question was how much effort would be expended to create the appearance a thorough investigation was made. Ironically, we’ve been told by high level insiders that Bank of America made a more serious go at performing these reviews than other major servicers did.

Thus the blame for this epic and costly fiasco rests squarely on the OCC and Promontory. The OCC apparently never bothered understanding that the root of the foreclosure crisis is the lack of integrity in the underlying records. This failing has been tacitly acknowledged in the astonishingly high error rates permitted in the servicing performance metrics for the state/Federal foreclosure settlement of early 2012.

The combination of the 2012 state/Federal and 2013 the OCC settlements putting band-aids on gangrene means that anyone who buys a house with a mortgage in America is taking a gamble that his servicer will abuse him.

Both of the roots of the foreclosure fraud crisis – strong servicer incentives to cheat on delinquent portfolios because they lose lots of money otherwise, and bad systems that result in borrower harm in even in the absence of malign intent – are alive, well, and will continue to plague the housing market. Promontory, which occupies a unique status in America as a dominant shadow regulator, has simply treated this disaster as another profit opportunity. And profit it did.

We will reveal what happened on the ground in the biggest review center for Bank of America, in Tampa Bay, in depth. The reason for this level of detail in Part III is to debunk some of the defenses that the major parties have or are likely to offer for their conduct.

In this post, we will give readers a sense of how the reviews operated, with emphasis on how murky the roles and responsibilities were. It is important to understand that this is contrary to how the reviews were intended to operate and to specific representations Promontory made to the OCC and Bank of America. Promontory was not simply ultimately responsible for the reviews; it was to handle all of the major tests directly or via consultants and contractors it engaged directly. As we will see, even from its early days, that was not how the project was set up.

We will go into a good deal of operational detail in Part III and will focus on ramifications and implications in our next two parts.

Complex, Chaotic, and Undermanaged Review Implementation by Promontory Masked Underlying Lack of Integrity of Systems and Processes

With over 2500 employees and temps spread over multiple sites, the foreclosure reviews at Bank of America were a significant undertaking plagued by:

Bizarre and changing definition of the role of the claims reviewers

“Mythical” participation of Promontory in critical data gathering and vetting

“Garbage in-garbage out” problem of unintegrated, unreliable records

“Fire, aim, ready” approach to launching the tests

We’ll discuss the first two topics, the role of the claims reviewers and Promontory, in this Part IIIA post, and the deficiencies in the underlying records and review process itself in Part IIIB.

Bizarre and changing definition of the role of the claims reviewers

One of the most peculiar features of the foreclosure review was the confused and contradictory role of the claims reviewers who worked on site at Bank of America. They were modestly-paid workers, subject to considerable regimentation in matters like their hours and attire, yet who were, at least until the content of their task was dumbed down by Promontory late in the review process, given substantial responsibility.

The main task of the OCC mandated foreclosure reviews was to determine whether and what level of compensation was due to borrowers who requested foreclosure reviews. 495,000 borrowers responded to letters sent by 14 servicers or to other outreach efforts implemented after a scathing June 2012 GAO analysis of the dismal borrower response and participation rate. Even so, there is good reason to think many eligible borrowers did not participate because they were unaware of or were intimidated by the review process. The maximum award was either $15,000 plus the return of a foreclosed-upon home or $125,000 plus any equity in the home at the time of foreclosure.

While both the bank and Promontory maintain that Promontory was conducting the reviews, as we’ll show, the evidence strongly indicates otherwise.

Promontory was engaged by Bank of America to act as the independent reviewer in September 2011. By late summer 2012, roughly 2500 people*, both temps working on Bank of America premises and Bank of America employees, worked in multiple locations, with the center in Tampa Bay the largest.

The backbone of the project was a software program called CaseTracker. It was the tool that contained all the questions from all the tests performed on borrower files, enabling disparate reviewers to upload documents and input information they obtained by reviewing Bank of America homeowner records, record computations and preliminary findings called “harm notes” and make additional comments. The program had extensive audit notes, so anyone who worked on a file could see how it was handled after he loaded it into the system, including how staff at Promontory acted on it.

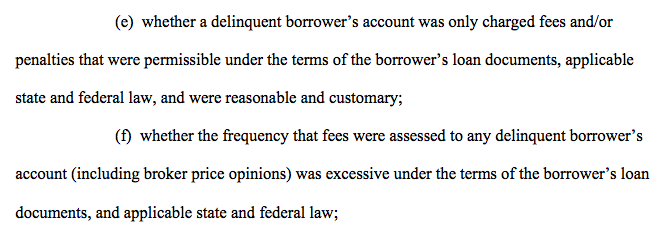

Despite Promontory’s commitment that it would handle the labor requirements of the reviews (see Promontory engagement letter, Attachment B, pages 9-10) Bank of America began hiring temps to work in Tampa Bay in November 2011. By that point, Promontory and the bank had apparently decided to structure the process as a series of tests designated A to H, with each test corresponding to a lettered section of the requirements of the OCC’s April 2011 consent order to Bank of America. For instance, test E was on the permissibility of fees and test F was frequency of fee assessment (as in, even if the fees were allowed, were they assessed more often than allowed). Here are the pertinent sections of the OCC order:

The bank organized and trained staff to work on tests A through G (see Appendix II for brief descriptions). Test H, the final determination of whether the deficiencies identified in Tests A through G hurt the borrower, was Promontory’s responsibility.

Initial file review (test A) consisted of basic tasks: seeing if the borrower actually had a loan serviced by Bank of America and met basic eligibility requirements for the review, determining whether the bank had a promissory note and mortgage at the time of a foreclosure. This part of the review was performed by clerical staff within the bank.

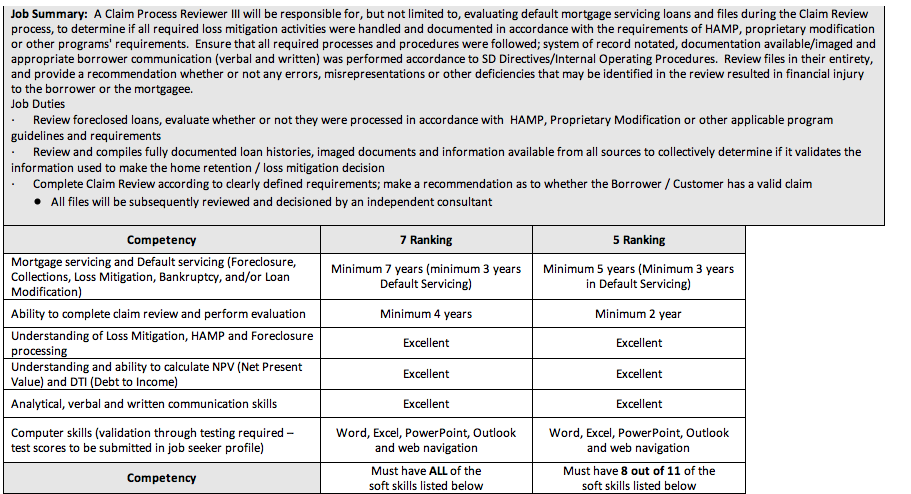

Bank of America sought out contractors who had meaningful experience in mortgage documentation and foreclosure processes for the roles Claims Reviewer Level II and III (see Appendix I for more detail). These Level II and III reviewers would work on the more demanding tests, B through G. In Tampa Bay, some Bank of America associates from the recently-shuttered correspondent lending department also worked on test B through G, but the whistleblowers estimate that over 80% of the staff in Tampa Bay were contractors.

The job description for the Level II and Level III roles make it clear the contract workers were expected collect documents and compile data, then perform a significant amount of research, review, analysis, and finally, to exercise discretion in determining results. These job descriptions came from Aerotek, the agency that recruited most of the Tampa Bay contractors. Notice the requirement that the reviewers be able to perform computations, like net present value and debt to income (click to enlarge):

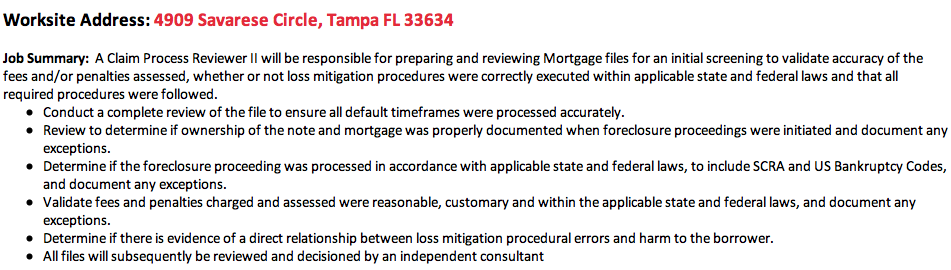

The Level II job description similarly sets forth responsibilities well above that of simple document retrieval and compilation of information. Notice also how they track the tests described in the OCC consent order (click to enlarge):

Many of the early hires (November 2011 through March 2012) exceeded these job requirements. Moreover, many individuals who met or exceeded the Level III job requirements worked as Level II reviewers because the higher-paid Level III slots filled up quickly.**

The agencies recruiting the contractors presented the assignment as one where they would have an important part to play in helping wronged borrowers obtain a measure of justice, consistent with the Administration’s messaging about the initiative. The temps thus believed their role was to complete the tests rather than act as document-gatherers for Bank of America on behalf of Promontory. In keeping, they received one week of training on the relevant systems and one and one half to two and a half weeks (depending on the tests they were assigned to) of training on their tests, and then spent an additional week to two weeks being certified. The training and certifications were performed by Bank of America employees, not Promontory.

Moreover, the Bank of America employees (the team leaders who over saw groups of 12 to 15 reviewers, and the unit managers and adminisphere above them) kept stressing that they were not managing the contractors.*** All the whistleblowers discussed how confused the governance was. For instance:

Reviewer B: I couldn’t even tell you what a Promontory person looked like. We would get advance notice that they were going to be in the building, and, you know, to keep your head in your computer and to focus on your work and make it look like you were working hard, and, you know, we would get told, “Oh, they may come around, and, you know ____ ” [crosstalk]

Yves Smith: So you’d get those kind of instructions from Bank of America people, even though they weren’t your managers –

RB: Correct… We had basically no manager. We had a unit manager and a team manager, and there were probably five to six teams for every unit manager, and, I mean, if we had something, if we were wearing something that was inappropriate, they would contact our agency and tell our agency to call us and tell us to go home and change…

They could manage us through the project as far as making sure that we had training, which we’d never had, proper training, making sure that we were using the guides that we were told to use, but when it came to actual HR, we, you know, you couldn’t even go to your manager and say, “Hey, can I talk to you for a minute alone?” They would say, “No, you have to contact your agency.” But when it came to Promontory being in the building, they had no problem making sure, you know, telling you want to do. It was a very odd situation.

YS: And when you had these questions, when you were told to interpret things in the most permissible manner, who told you that, gave you those kind of instructions?

RB: The team managers and the unit manager.

Before assuming the reviewer confusion simply reflects a lack of sophistication, the confidentiality agreement all the temps signed shows a similar pattern of managerial inattentiveness. It’s defective legally: there is only one party to the agreement, the contractor, and no governing law or term is specified (although it does have the expected survivorship clause). It defines “Confidential Information” as propriety (etc.) information disclosed to the “Recipient” (the temp agency) when the temp agencies never received any access to customer records or the content of the tests, presumably the information the bank and Promontory were most concerned about.****

And in case you thought the agreements the contractors signed with their agencies mean the agencies constructively received the information, think again. Most of contractors we spoke to had no written agreement of any kind with their agency (and remember, some came from the agency that employed most of the Tampa Bay temps). Amusingly, the only document formalizing one contractor’s relationship to his agency was a printout with his regular and overtime rates, sent after the assignment had started, stating the agreement was “oral”.

Documents provided to some of the contractors in advance of their first day on assignment included a PowerPoint presentation on Bank of America’s servicer dress code, along with ones stating that Bank of America (as opposed to Promontory) was the agency’s client.

The peculiar work structure, with Bank of America distancing itself from certain types of management responsibility for temps it was paying for directly, may have resulted from the desire to preserve the fiction that Tests A through G were under the control of Promontory, not the bank. This is important because the April 2011 OCC consent order explicitly required the independent reviewer to conduct all the tests, not just the assessment of harm.

Although the contractors report that while the Bank of America managers exercised a great deal of control over their work environment (for instance, they were forbidden to sit at their desks more than five minutes prior to their shift and were hectored if they were more than a minute late), they nevertheless did not directly control their activities. Thanks to the instructions from the agency that the contractors were to help homeowners, plus the amount of time dedicated to training, many of the contractors were diligent about probing for and finding evidence of harm to homeowners. As we’ll see in Part IV, Bank of America worked systematically against that, meaning it opposed the efforts of the low-level workers it was paying for.

Another reviewer confirms that the reviewers had considerable latitude in how they executed their tests:

Reviewer D: Yeah. That changed too. Initially, you know a lot of us were initially told to go look at the borrower complaint.

YS: Mmhmm.

RD: But then there was a different school of thought, don’t bother looking at the complaint because, you know – and this is my, the way I felt is, I’m not really going to put too much weight in the borrower’s complaint because the borrower doesn’t necessarily know all the ways they may have been wronged.

YS: Yeah.

RD: So the borrower may be complaining about something that, you know, was actually done correctly, but we might have screwed them over someplace else.

YS: Yeah. Yeah.

RD: So I didn’t really – I reviewed the whole file completely independently.

“Mythical” participation of Promontory in critical data gathering and vetting

Despite the fact that the reviewers were putting extensive amounts of information and test harm notes into CaseTracker,

Promontory spent virtually no time at the Tampa Bay site. They seemed content to rely on a “quality assurance” department which was staffed by and under the control of Bank of America.

The reviewers were told that Promontory would be visiting the site monthly, and the OCC every other month. Yet none of the whistleblowers, including the ones who were there 12 months, recall more than three visits by Promontory. When they visited, Promontory employees did not walk the floor or chat with the reviewers freely. Instead, a few of the reviewers were chosen to meet with Promontory (and when the OCC visited, the OCC along with Promontory) in small groups called “round tables”. These participants were briefed by Bank of America before the meetings and instructed not to volunteer information, only to answer questions. It was important to stay on good behavior in these meetings. One reviewer was dismissed immediately after participating in a round table.

One of the whistleblowers had been included with a round table with both the OCC and Promontory and said the OCC was concerned mainly with whether Bank of America was pushing the reviewers to meet production goals. During one site visit, Promontory, along with the OCC, attended a training class given by one of the proficiency coaches (meaning one of the Tampa Bay staffers) to about 90 people on one of the major tests. Why was Bank of America and not Promontory conducting these sessions?

Otherwise, Promontory was inacessible:

Reviewer A: And we couldn’t, we were told time and time again, you can’t e-mail Promontory and ask questions. You just can’t.

YS: Mmhmm. Mmhmm.

RA: Which, oftentimes, you know, we would sit around for days and weeks waiting for answers from Promontory because we couldn’t ask the question directly and we had to wait for it to –

YS: Filter through.

RA: – go through the proper Bank of America channels to finally get to Promontory and come back to us, and that always made it suspect because it always came out in favor of the bank, whatever the question might be.

Promontory would likely maintain that these criticisms are irrelevant, and would claim, as it did in October 2012 in an article by ProPublica questioning the independence of the review process, that it was doing all the substantive work:

Promontory spokeswoman Debra Cope said Bank of America’s employees “are responsible only for the clerical work of assembling the documents and files.” Promontory employees analyze the material assembled by Bank of America “independently with no involvement from [Bank of America],” she said. “We perform all the tests.”

When Promontory said “all the tests” that meant all the tests A through H as set forth in the OCC consent order.

However, if we look at the job descriptions, the number of tests performed by Bank of America employees and contractors, the structure of the workflow, and the ambiguity of many of the questions that the lower level employees were required to answer, it is apparent that the Level II and III workers were performing the overwhelming majority of the B through G tests, which were critical to any determination of harm. They also prepared extensive harm notes, which were clearly intended to be input to Promontory.

Moreover, prior to the very last week of December, right before the project was shuttered, the workers did not provide enough in the way of underlying documentation and information from Bank of America systems for Promontory to be able to perform the B through G tests. It was only then that revised test questions and procedures were rolled out to reduce the Bank of America staffers to the purely clerical role described above.

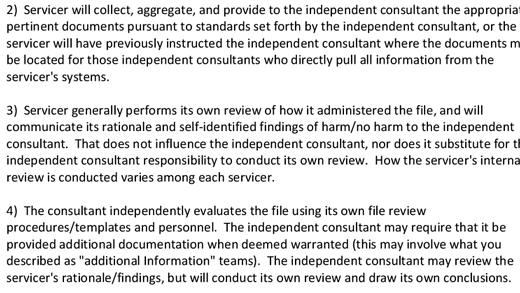

In keeping, the OCC, a mere week after the grand Promontory assertion that it was performing “all” the tests, undermined that claim. The OCC admitted the review process had changed from that set forth in their orders. The OCC admitted the banks were self scoring the files and sending their opinions to Promontory, with Promontory then making its own determination.

While this may not sound troubling, the structure of the work indicates that it was the reviewers, and not Promontory, that was making many important substantive decisions before the information was sent to Promontory. (This process could be used to subvert any findings of damage to borrowers. In Part IV, we’ll discuss in detail the many ways findings of harm were suppressed.)

For instance, the reviewers would compile “harm notes” on the detailed questions in each test. Reviewers on tests E and F would compute the amount of impermissible fees. As mentioned above, these findings would then be sent to a team called “quality assurance” which the whistleblowers called QA or QC and was under the control of Bank of America. QA would regularly push back on any findings of harm:

RB: Right. Well we would review the file, then it would go to our QA department, who would then review the file, and the QA department had less training than the rest of us. Some of them were brand new –

Yves Smith: Oh, wow.

RB: – and came to the project later on, so then they would inevitably take it back to us for, you know, something that they thought we should fix, and we were given the opportunity to either agree with them or, you know, just rebut it, and our manager would have to then send it back to them, and then it would go to Promontory from there if it passed their review too. So there were at least two different departments at Bank of America that touched it before it even got to Promontory.

Put it another way: why would the QA Department push back against reviewer findings, and why would the reviewers be given the opportunity to rebut it, if they were not doing substantive analytical work?

Similarly, if you look at the detail of the tests, you can see the reviewers are doing granular tasks that were highly unlikely to be replicated or independently verified by Promontory.

Bank of America Foreclosure Reviews – EFAT Primer by

For instance, on page 10 (heading “F. Add New fee”) the Level II reviewers were instructed how to break down a dollar amount into underlying components and record if any of those components were impermissible:

For example, the Capd Fees and Escrow fee (10153) is the lumped fee that includes both the escrows and fees capitalized as part of the loan modification that occurred on this loan. Since this fee includes multiple fee types or items, it might be necessary to break it down. Let’s just say that during the review, the claim researcher has determined that the capitalized fee as part of the 10153 fee contains impermissible fees but the escrow portion is permissible/correct. The “Add New Fee” feature will allow you to split this fee into 2 distinct fees. Now you can exclude the escrow portion while applying limits to the fees.

Similarly, on page 11:

Once the each fee is located, manually input the limits for the fee based on loan docs, state or investor guidelines. Provide a concise comment to explain the reason on why the fee is being flagged as impermissible. Select the appropriate “Refund or ADJ”. Repeat this for all fees found to be impermissible.

In other words, CaseTracker did not capture underlying documents (the state or investor guidelines) for Promontory to reviews the accuracy of the work done by the reviewers. They received summary information that reflected a considerable amount of underlying analysis and judgment.

The reviewers did say that there was an effort ongoing to simplify (“optimize”) the tests. But they did not believe that it resulted from a recognition by Promontory that it was at risk if it continued to delegate as much responsibility to the low level claims reviewers as it had, or to lower costs to Bank of America. They instead noticed a pattern of simplifying the tests to eliminate questions that would lead to findings of harm. And they also reported that they were not directed (at least prior to the last week of December) to upload documents or information into CaseTracker that would allow someone at Promontory to do this sort of analysis instead. As one reviewer described it:

The 2200-question test that you just mentioned was actually the G test. That was the test that would examine modifications and forbearances and so forth in depth…. Oh, it was 2200 because it was 50 different states, so in each state it might be only so many, it would only be a fraction. Eventually narrowed it down to 500 questions because they took out state-specific laws…

These tests would start out in massive proportion and actually be whittled down to virtually nothing, and any question that would, in my opinion, that would direct you to harm was eliminated, and particularly in the G test where they took out questions on state-specific laws that would indicate a procedure wasn’t followed properly. So, yeah. Those tests were pretty much manipulated to become very benign.

As the tests were simplified over the course of 2012, Bank of America also lowered the pay rates and skill requirements of the temporary staffers it was bringing on board in Tampa Bay. But through November 2012, the Level II and Level III workers believed that they were performing tests B through G, and the elaborate review process confirms that (recall that when a reviewer submitted a completed file, it went to the Quality Assurance department. QA could send the file back noting their objections to findings of harm or flagging other issues. The reviewer and his team leader would have the opportunity to rebut QA before the file was sent on for other tests and then to Promontory).

In November, in the wake of an article by ProPublica questioning the independence of the reviews at Bank of America, the workers in Tampa Bay were told Promontory had not been using their analyses or harm notes, and had been doing the tests themselves.***** This was a typical reaction:

Reviewer D: So all the time we spent on all those files was just a waste because Promontory was supposedly not looking at anything we did.

YS: Do you believe that statement or not?

RD: No. No.

In keeping, many of the reviewers continued to perform the tests in the way they had been taught, which included making harm notes.

In December, ProPublica published an article that in its headline depicted the Bank of America controlled reviews on tests A thought G as a “cheat sheet”. Even though the negotiation of the settlement was well underway, the story appeared to have provoked a response from Bank of America and Promontory. One reviewer reported:

Get this shit…The article was dated Dec 17th. Things were pretty slow at work that day. The very next day all the proficiency coaches received a last minute meeting invite for that morning. In that meeting I heard they were told that the optimization had been approved and that they had to scramble to learn the process and prepare materials so they could start the first training class the very next day at 9AM! From that moment forward they were holding 2 classes a day until everyone was trained. The urgency made no sense to me, especially since it was a few days before Christmas and we had so many people that were on vacation!

The other reviewers confirmed that it was not until this rushed training was completed that the procedures were in place that the workers in Tampa Bay were merely extracting and compiling information for further review by Promontory. That new process was effective for the one remaining week before the settlement was signed and the temps were dismissed.

In the second post in Part III, we’ll discuss why these reviews never could have been completed properly and how the half-baked implementation by Promontory only made a bad situation worse.

_______

* Bank of America reported that 1750 employees were working on the reviews as of October 2012. Our whistleblowers say that the number of participants on periodic project-wide conference calls prior to that date were roughly 2500. It is highly unlikely staffing was smaller in October. It is thus likely that the discrepancy results from the number of contractors working on the project, which were an estimated 750 in Tampa Bay alone.

** As the tests were simplified and the roles were downgraded, the bank recruited lower skilled workers at lower levels of pay to fill the Level II and III roles. More on that in Part IV.

*** They may have meant that simply because the contractor relationship meant that human resource type issues like dress code infractions and changes in schedule needed to be handled through the agency. However, all the interviews make clear that the immediate supervisors, meaning the team leaders and unit managers, interpreted it more broadly.

**** Bank of America was not as reckless as the defective confidentiality agreement suggests. The reviewers sat in a cube farm and were monitored closely. They were fired if they e-mailed anything to personal e-mail accounts, even cases when it was simply a joke or a stern message a non-manager manager. Use of the printers was also monitored and regarded with suspicion. However, lapses involving Promontory information merely resulted in scoldings. As a practical matter, the bank’s leverage over the employees was due to the fact that they wanted to continue on the project.

***** If this were true, it also raises the question of why the contractors were hired in the first place, since Promontory had access to the same systems that the Tampa Bay staffers did.

Formidable, Yves. No wonder you’ve been so busy. None of this is surprising but its good to see hard core evidence and documentation.

I’ll have to read Part IV a bit later, but as we all know, their mortgage servicing departments didn’t have the staff to handle the volume of loans they were carrying. I noticed in a Bank of America disclosure they’ve reduced their number of total employees by 20% in 2012 but have increased staffing in their mortgage servicing department by a full 20%. It must be bad if they’re giving them that much more help, in spite of having sold off some of their servicing business and all of their litigation losses, another $10 or $11 billion in their settlement with FNMA. Their legal expenses alone were well over $1 billion last year!

Thanks, Yves. It’s a lot to digest. Great work.

Indeed.

Great work, lets hope it makes a difference.

Yves you rule.

Hope these guys get punished. There needs to be an enlightement campaign for the average person to understand how criminal this is. The banks are not yet fully equated with organized crime. We gotta get that done.

So why not do your part to help it make a difference?

1. Tweet it

2. Comment on it in other blogs and link back

3. Write/e-mail your Congressperson, especially if s/he is on one of the banking committtess or Oversight, cite this with a few sentences of your own and demand an investigation. That means YOU, craazyman, Carolyn Maloney says she was unhappy about the settlement. 10 letters/e-mails to Congresspeople on a topic that isn’t a front page news item is a lot, so you can get a big part of the way there

4. Write a letter to the editor local paper along the lines of 3 if you live in a high foreclosure state. Congressman also pay attention to the papers in their district

Letters to the editor are very effective. They get read and discussed locally, and Congressional offices look for them.

Many local papers will also allow people to write Op-Eds. We had a lot of success fighting the landfill with that strategy.

(The local angle might include the theft of recording fees.)

So basically, Promontory got paid money for doing absolutely and utterly nothing. The human tragedy of so many people engaged in a meaningless process goes beyond dystopia fiction. Can screwing up this comprehensively and this badly really just be a result of incompetence?

more like it was all designed for appearances only:

Jeffrey Brown

Managing Director, Promontory

Jeff helps clients meet regulatory expectations for capital planning. Having served as senior-most economist at the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, he focuses on ways to demonstrate to regulators that banks understand their risks and that they can manage their capital positions to adequately address those risks. Jeff also draws on his decades of experience as a quantitative economist and senior bank supervisor to help clients on all aspects of governance and risk management.

http://www.promontory.com/Bios.aspx?id=867

and Paid Exorbitantly

A Potemkin process that covers up a great crime is worth a lot of money. Whatever Promontory’s was paid, I’m sure that BoA’s criminal executives — sorry for the redundancy — consider it money well spent.

This blatant interference by B of A is so mind boggling. I betcha they never thought anyone would be smart enough to expose the whole labyrinth of deception they attempted. I’m marveling at what a very convenient thing agency is. If anyone delved into MERS it would be at least this bad.

No doubt that’s why Test A was done strictly in house.

Time to start sharpening the pitchfork…

Outstanding. I will be trebling my donation today. Why is it the absolutely best journalism is on NC?

More importantly…how do we as a community change the dynamic so that regulators enforce laws instead of creating lucrative intermediaries that exacerbate the rampant fraud and corruption? Aside from outright revolution that is…

in other words our ( I mean their government) is a partner in crime.

Aaaaand its gone!

In 2000 as a CA licensed Real Estate Broker I had the ability to arrange mortgages from my home and send them to the funding agency. I also had a fiduciary duty to my clients to follow CA State laws. In the Gramm-Leach bill of 1999 they stated they were exempt from state laws and from prosecution. Not only were they not going to pay recording fees, they were not going to keep adequate records. Now big bank mortgages are provided using bank employees under the Department of Corporations. Keeping adequate records was never the intention of the Big Banks. Therefore any home could be a potential time-bomb when problems arise requiring adequate records and “chain of title” especially tracking ownership of a mortgage. Until this problem is solved, we have a lawless real estate system. Thanks for your hard work.

At the end of WW II, the U.S. set out to punish Japanese military personnel who had treated POWs with great cruelty. Many were rounded up and thrown in jail. Some were quickly convicted. Then the Cold War began, and the U.S. decided that it needed the good will of the Japanese. Virtually every war criminal, whether convicted or accused, was released from jail, no questions asked. The only ones who ended up punished were the few who had already been executed.

I raise this historical analogy because that’s how I think the Obama Administration views its amnesty toward the banks. They see it as a world-historical imperative, one that they would privately grant is morally unseemly when measured on its own terms, but that they view as necessary in the service of saving the world from the greater threat of financial collapse. They view their role as “leaders” as requiring some morally noxious actions in the service of the “greater good”. Of course the problem with this line of reasoning is that it presumes that no alternative existed to amnesty for the banks. That’s where the intellectual capture and campaign contribution capture have caused them to assume that there was no alternative to the current path.

A rotten shame.

‘that’s how I think the Obama Administration views its amnesty toward the banks.’

You may be giving the Obama administration too much credit.

From the beginning, Obama received more money from the financial industry than any presidential candidate in U.S. history

Don’t underestimate the great believer’s capacity for self deception. Obama loves to see himself as an historical figure. Fraud Guy’s point is well made imnsho. I learned a little history in analogy and give it credit for being apt if not 100% accurate as as psych assessment.

It’s hard to tell in which measure how much of Obama’s complicity is due to arrogance, ignorance and innocence, but as much as I loathe the man I’m not convinced his motives are purely self aggrandizement. Ingratiating I’ll believe.

Promentory has been running this scam for a long time. I used to be involved in Patriot Act/Anti Money Laundering Compliance industry working with the largest banks in the world. Every time there was a regulatory action, Promentory was brought in to be the overlord. The running joke was that there the OCC and FRB stapled Ludwig’s business card to consent orders.

To Dennis and all others involved in the research and getting the word out: THANKS!!!!! This whole era from 2008 to present represents such a sad time for our nation as to the integrity that politicians and the financial community have displayed. So much of what they have done unquestionably violates the laws on the books yet instead of using the tools, like laws–on the books, politicians said the financial community was too big to fail and looked the other way while Lenders continued to abuse their borrowers. Then to add insult to injury, legislators pass more laws that only hurt the small and independent lenders to give more favor to the BofA’s that so abused—and continue to abuse—their clients. . .