Bethany McLean just released a piece at Reuters which presents a good overview of the Department of Justice case against rating agency Standard and Poor’s for its conduct in rating residential mortgage backed securities and CDOs.* The high level description of the case, in particular, why the government used FIRREA (a statute designed to protect federally insured banks against fraud) as its cause of action, is helpful.

I have mixed feeling about taking issue with McLean, since she generally does a fine job of reporting and analysis, but there were some things about her piece that were so surprising that I thought they really needed to be discussed.

Now there are reasons to dislike the case. The biggest in my mind is why it has taken so long. The Feds have been cautious and slow about launching any cases, consistent with their “don’t rock the boat, and don’t threaten any big financial players fundamentally” posture. Frankly, the media does not give enough credit to Ed DeMarco of the FHFA, whose putback suits against 17 servicers have the potential to claw $200 billion back. This suit, and not DeMarco’s refusal to have the GSEs offer principal mods to investors, is almost certainly the reason Obama was keen to replace him (highly unlikely now give the recent adverse appellate court ruling on recess appointments). While S&P could be hit with serious damages, none of the Obama-administation launched suits were anywhere near as threatening to a major financial player.

So what are McLeans’ beefs? She had three core ones:

1. The case presents the banks as victims, which is “weird” (Jonathan Weil at Bloomberg voiced similar reservations)

2. S&P didn’t make all that much on these deals, so why them?

3. And what about Moody’s?

“Weird” is a rather imprecise objection. It’s pretty widely known that the ratings agencies First Amendment defense, as nutty as it seems, has proven remarkably effective. Using FIRREA might enable the Feds to surmount it. This is as weird as going after Al Capone for tax evasion.

As for the aesthetics, that the FIRREA requires that the banks be depicted as victims, it depends on what you mean by “bank”. In fact, producer level employees (heads of profit centers) at all save well run firms (that list probably stops at Goldman**) are seeking to maximize their returns, and that often includes gaming the firm’s systems and pay policies. This is why Bill Black’s accounting control fraud idea is inadequate when dealing with a financial firm that has large trading operations. The looting occurs not just at the executive level, but also at the profit center level. Hence the expression, “IBG, YBG” for “I’ll be gone, you’ll be gone.” That refers to the widespread practice of doing business or putting on trades that show profits this year but have good odds of blowing up down the road.

So what really happens is the traders and other producers are out to maximize current year apparent profits, the hell what happens later. So the folks who ran the RMBS and CDO operations were in cahoots with the ratings agencies.

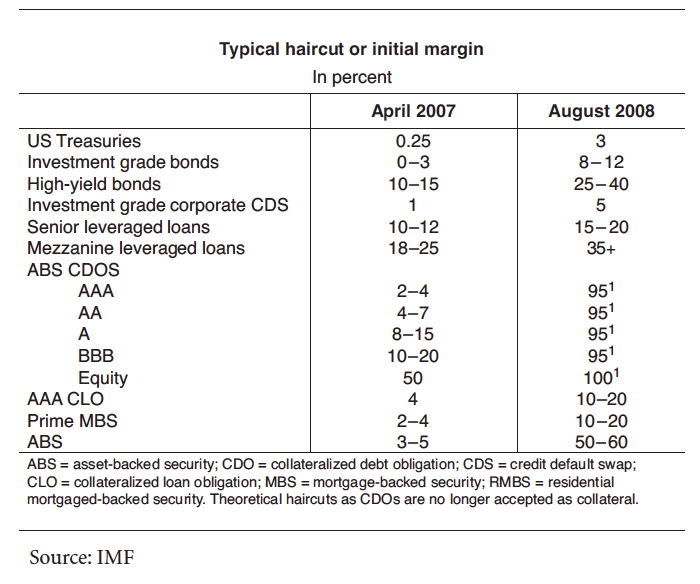

Did senior management understand what was going on? McLean says Citigroup might indeed have been duped. I’m surprised she didn’t include Merrill (not specifically in relationship to the suit, since only federally insured banks are concerned, but as an example of a type). The firm made a decision to triple its CDO business in 2006 over the warnings of a well regarded MD who was effectively forced out. That decision left Merrill holding a lot of drecky CDOs when the music stopped. In Europe, all the major dealer banks that had adopted Basel II saw AAA rated CDOs being used to game bonus systems. The higher-ups never questioned their value until it was too late. Look at the change in haircuts on AAA CDOs:

A haircut of 95% effectively means no one will take it.

What about the firms that weren’t as dumb as the Europeans or Merrill and Citi? The other pattern is that management was a quiet co-conspirator with producer abuses. After all, the more profitable a firm looked, the bigger the bonuses they got too. Key to this strategy was having large, busy, but politically weak risk management departments. So management could pretend it didn’t know there was gambling in Casablanca, indeed, it had taken efforts to prevent gambling. Right? So again, the victim was the “bank” but in this case we mean the firm as distinct from the people operating it. As Sallie Krawchek observed back in her days as a securities industry analyst as Sanford Bernstein, it’s better to be an employee of a Wall Street firm than a shareholder in them.

Now let’s go to McLean’s second objection: the profits were minuscule compared to the possible damages. Isn’t there something wrong with this picture? Actually, no. In fact, this is another fundamental Wall Street design factor. Diffuse responsibility as much as possible and park as much as you can with firms or entities that have little in the way of a balance sheet. After all, the whole point is for the people who made the serious money to keep it!

One version of this approach was in the use of CDO managers. As you may recall, banks had this nasty of designing CDOs that were meant to fail for their own purposes (to get the garbage off their balance sheets) or on behalf of subprime shorts. Here is what we wrote about who might have liability on deals created by the hedge fund Magnetar in ECONNED:

Anyone involved in these transactions probably understood the implicit logic, even if no one acknowledged it. But there is a remarkable absence of anyone who could be pinned with liability. Magnetar officially had no legal relationship to these deals. The investment bank packager/structurer was off the hook as long as he made reasonable disclosure (and remember, the standards are much lower here than for instruments that fall in the SEC’s purview). The rating agencies get off scot-free, thanks to their First Amendment exemption (discussed in chapter 6). The lawyers involved in the deal are responsible only to their clients, meaning the structurer/packager, and cannot be sued by unhappy investors. The only party on whom liability could be pinned is the CDO manager.

And who was the CDO manager? Typically a shell with pretty much no equity. The joke was that the typical CDO manager was two guys with a Bloomberg terminal.

What about McLean’s third objection, why no suit against Moody’s? Well, it actually does not make sense to sue a bunch of firms at once, believe it or not. The FHFA filing suit against 17 servciers at once is unusual and driven by statute of liability concerns. You want to get at least one case under your belt if your are using a new legal theory (which the DoJ most certainly is) before you go after other targets.

Moreover, there is reason to think, despite the fact that it engaged in precisely the same conduct, that Moody’s might be a harder nut to crack. If you’ve been following the case, it is built largely on damaging e-mails.

Brian Clarkson, first the co-head of the structured credit group and later CEO of Moody’s, succeeded in creating a reign of terror. That may sound like an exaggeration, but there are ex-Moody’s people who have him in the “he who must not be named” category, like Voldemort. This is an extract from the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission testimony of Mark Froeba:

Moody’s campaign of intimidation included all the run-of-the-mill techniques you might find at any company. Cooperative analysts got good reviews, promotions, higher pay, bigger bonuses, better grants of stock options and restricted stock. Uncooperative analysts got poor performance evaluations, no promotions, no raises (or effective pay cuts), smaller bonuses and fewer grants of stock options and restricted stock.

But Moody’s primary tool for implementing the culture change was a person not a technique, Brian Clarkson. In this task, Brian was especially adept at threats of employment termination. As my former colleague at Moody’s, Richard Michalek testified before the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations about Brian:

[Any] discussion of his management style included the words ‘fear and intimidation’. That description was periodically reinforced by the terminations of one or another of his managing director reports who had in some way failed to fulfill the express or implied expectations. The effect was only the more chilling when he was heard to say ‘it’s not personal, its only business’.

I think I can say, with only a little exaggeration, that I have heard Brian conjugate the verb ‘to fire’ in moods and tenses most grammarians do not even know exist. In my ten years at Moody’s, I do not think I had three consecutive encounters with Brian in which he did not threaten to fire someone, describe someone he had fired or identify someone he should have fired. However, several anecdotes are memorable.

Brian was notorious within Moody’s for a joke he told that would not have been funny even if it had been a joke: that his only regret in firing 20-some people from Moody’s RMBS Group was that one of them got a job before he could fire him. I am sure that few of us who heard him believed he had any regrets.

Brian even threatened to fire people before he had hired them. When I interviewed with Moody’s in September of 1997, he spent almost half of our meeting telling me about people he had fired and why.

Now why is Clarkson relevant? He was abusive, but he was also extremely protective of his and the firm’s image. People I know who left Moody’s before the Clarkson era was in full swing think that it’s likely that Brian would make sure that if he caught anyone saying something like the famous S&P email where a firm employee complained that they’d rate a deal if it was structured by cows, Brian would at least harangue them and make sure everyone knew not to denigrate the firm’s work in emails. So if this theory is correct, there won’t be as much readily-findable dirt at Moody’s. The DoJ will have to depose former staffers, which is a more costly and time consuming process.

Yes, I’d much rather see the officialdom going after executives at big banks. But the ratings agencies were and are an essential part of the toxic asset creation factory. It’s still useful to mount a case against them, even if their First Amendment protection means it’s not the straightforward sort of action many of us would like to see.

_____

* I hope readers will refrain from the “this suit is retaliation against the S&P downgrade of the US” line. Anyone who runs that line has not done the most basic fact checking. The investigation of S&P was launched before the downgrade threat. Jane Hamsher has examined the timeline in detail and argued that the downgrade threat was an effort by S&P to ward off legal action.

**Goldman is a well run shop. To what end the firm is operated is another matter entirely.

After reading Barofsky’s book “Bailout” it’s very hard to take seriously the idea that the Revolving Door Government that’s replaced democracy in the United States is really very interested in doing much to interfere with its Social Predation business model. So OK the DOJ have been treading water for the last four years in assembling its ammunition but Barofsky makes clear it’s a signal from very high level that allows that ammunition to be fired and I still think this attempted civil action against S&P is a shot across the bows of all rating agencies not to play party politics on monetary issues. If S&P has to be liquadated it will probably be re-badged by McGraw Hill buying up one of the smaller agencies.

Shot across the bow The exact figure of speech that struck me the day i read suit had been filed.

When you read they are seeking $5 billion in fines and an admission of guilt you realize they could have lead them a bit more in that shot across the bow.

Actually, it made great sense to go after Capone for tax evasion: it was the one charge the Feds could make stick. Other offenses – murder, blackmail, traficking, prostitution, etc – never made it to trial because key witnesses would change their stories (i.e. were bribed or did so to avoid having their families killed), were killed or simply disappeared. It’s better to get a known criminal off the streets and in jail where the harm they do to society is lessened (obviously, organized criminals can run their systems from jail, it just is a lot harder and a lot less rewarding).

Hence my reading on the S&P case that in each point of the case they are making the case that S&P knew it was doing wrong (criminal activity), that they did it to make money (motive) and that they actively aided their partners in crime (the mortgage securities issueres) to clear out their inventory before bad ratings came out (again, clear criminal activity).

Better to nail them on that and set the precedence that the rating agencies can’t rely on First Amendment defence for outright criminal behavior: what is being charged isn’t that they were wrong on their ratings (which is why others sued them), but rather they engaged in criminal activity for a profit motive repeatedly and deliberately.

If they can nail them for that, it’s as good as any other reason. If they can’t nail them for that, then regulations governing the rating agencies – if not all commercial activities – are worthless and we need to start over.

“Weird” is a rather imprecise objection.”

Weird because bankers used terms like “steaming piles of dogshit” to describe portfolio’s they told customers were solid? If SP stamped as AAA and the burden is on them, how did bankers know they were dogshit?

“So what really happens is the traders and other producers are out to maximize current year apparent profits, the hell what happens later.”

See Pettis post on how stability in the banking system can be harmful. I.e., rent seekers,undue risk taking in a “stable” system because the State has your back. After reading the Pettis piece it appears the US gov and banking system of today is atavistic in their actions

The only way justice will be done is to convene a grand jury and make use of the RICO statutes. Individuals, not institutions, need to face the prospect of jail time and the loss of their personal fortunes. Once that happens the dominos will fall and trials can begin.

“Now there are reasons to dislike the case. The biggest in my mind is why it has taken so long.”

…Agreed.

“The Feds have been cautious and slow about launching any cases, consistent with their “don’t rock the boat, and don’t threaten any big financial players fundamentally” posture.”

Any thought, then, on why Uncle Scam would be doing so now at a time when “beggar my neighbor” currency devaluations are becoming extraordinarily fashionable (all sophistic denials from junior Treasury officials notwithstanding), the likes of which are no less likely to result in a wave of bank insolvencies than was the case in the 1931-1933 period?

This is an outstanding piece. Just the kind of thing that naked capitalism does best.

Hopefully there is some serious will behind this case and it will help get the ball rolling on some accountability. At the very least, we need to put some fear back in the hearts of the big financial players.

Thanks, Yves!

Your footnote is simply wrong. S & P issued its downgrade threat in April. Moody’s followed with its own warning on June 2nd: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/03/us/politics/03congress.html?hp&_r=0

As you can imagine, since the WH is a tool of the banking cartel it commenced its SEC investigation in June against both SP and Moody’s as a clear warning to go no further: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/financialcrisis/8583387/SEC-investigates-role-of-ratings-agencies-Moodys-and-Standard-and-Poors-ahead-of-the-financial-crisis.html

Moody’s got the message. S & P did not get the message and issued its downgrade in August. S & P is now facing a $5billion enforcement action filed five years after the event.

Moody’s is not facing an enforcement action. Citi is not. B of A is not. Wall Street is not.

Your idea that Moody’s CEO was belligerent therefore its unlikely that anyone at Moody’s would have written incriminating emails is a stretch. Belligerent managers would actually cause more chattering.

There is a strong circumstantial case this is retaliation. Also, the case will damage S & P. Moody’s thinks so: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/financialcrisis/9872710/Moodys-downgrades-SandPs-parent-company.html

Destroy S & P and their downgrade won’t count for much anyway.

Nicely done, laying out the succint chronology, based on which the circumstantial evidence of retaliation is strong indeed.

“Destroy S & P and their downgrade won’t count for much anyway.” Yes, and also, possibly no more S&P. After which “and then there were two,” or, realistically (who hears about Fitch anymore), one, aka Moody’s. A nice Monopoly of One in the ratings branch of the Financial Predation Machine. One can argue, of course, that it’s only reasonable to thin out the players in the ratings game given how few banks are left after the Pacman Feast orchestrated by Fed and Treasury basically left only 3 banks/i-banks standing. As you said, Citi/BoFa/Wall Street they are not.

That may turn out to be true, LF. I can’t remember the exact timeline, it occurs to me S&P had to notify the administration of the possibility of a downgrade.

There were some serious back and forth discussions between the two concerning the downgrade lasting a few months.

What really stinks is the absolute lack of trust in our government to tell the truth, much less do the right thing. Policy seems to revolve around very crappy and vindictive political ends, and much speech and fanfare around the one or two minor shows of reponsibilty. There are some serious credibility issues that need to be overcome, but won’t.

If the government told me the sun was out, I would have to look out a window to confirm it.

Yves, you say that GS is a well run shop. As a lay observer on matters involving finance, I wonder how that squares with the massive GS exposures which had to be bailed out by the Fed (including via the backdoor AIG “bailout”). I’m not being facetious at all. I’m really wondering if that sort of condition is just considered par for the course (and therefore *not* a sign of poor management) in terms of well run investment banks. Thanks!

Bethany McClean really only brought to print what a number of people are quietly wondering.

One point, and maybe a considerable one is that seeking $5 billion in fines or damages is absolutely unheard of in any SEC, or DOJ suit following the financial crisis. So $5 billion and an admission of guilt is what they’re playing for.

The largest award that I can think of was GS settling for $500-600 million and an admission of wrongdoing concerninig the Abacus deal.

I’m thinking UBS or Credit Suisse may have been fined or settled for something like <$2 billion in the LIBOR scandal or aiding tax evasion…I can't remember off hand.

This case, at $5 billion is astonishing.

Yves, I love that IMF chart and have nearly committed its info to memory.

But what was the haircut for “mezzanine leveraged loans” in September and November of 2008? THAT is the info I need but cannot find anywhere.

The haircut had to be much higher in September than it was in August, much higher than 35%.

Here’s my transcription of Chris Seefert’s FCIC interview of Lloyd Blankfein, beginning at roughly the 31-minute-mark of the interview, available here:

http://fcic.law.stanford.edu/resource/interviews

Chris Seefeert: So describe for us, if you can, the volatile markets that occurred in ’07 and ’08. What were the areas in terms of derivatives that were the areas of concern for you guys?

Blankfein: I’d say the biggest asset class that I was concerned with . . . for this, ah, . . . maybe I’m fuzzed up on what the period was . . . Was it 07, the beginning of 07 or the end of 07? But I’d say when the credit crunch started the most important thing for us was our credit book, our leveraged-loan book. Because that was the bulk of our risk, that was a much bigger business, much bigger exposure [than Goldman’s exposure to mortgage bonds].

We’re one of the biggest firms in M&A. As a consequence of doing M&A, we end up . . . [holding bridge loan exposure to PE-firms for their LBOs].

So as a result of that we had tens of billions of dollars — maybe over $50 billion of exposures to leveraged loans — in such illustrious names as Chrysler, and, ah, you know, a million . . . [inaudible].

And in those periods, because those [leveraged-loan] positions were kinda big, concentrated — everybody knew who had them because generally it was the financiers of the underlying transaction that ended up with the big pools of bonds, ahh, it was very very hard to sell them [the leveraged loans], except at distressed prices, which we were willing to do.”

I’d guess the haircut on levered loans — in September 08 — was at least 50%, so Goldman had an “unrealized” loss of $25 billion on their $50 billion mezz-loan book. And Goldman’s competitors had similarly-sized losses. Obviously, the Fed’s policies saved them all.

But my question remains: What was the haircut for mezz levered-loans September – December 08?

IMF data for August 08 is useless because the meltdown was only beginning then.

@TBV. Thanks for finding some of the exposure numbers at GS. So do you think that GS having this type of exposure was consistent with GS being a “well run shop” — presumably, given that all of its competitors had similar black holes of exposure?

Floyd Abrams, one of S&P’s lawyers claimed on CNBC, February 5, 2013 that S&P is not “going to make a 1st Amendment defense” [in this case]. The parent, McGraw-Hill, has hired John Keker to defend. Let’s see if the DOJ uses the case

to investigate on exactly how S&P committees produces their “opinions” on a “CDO by CDO” basis. These particular CDO’s cratered a Federal Credit Union.