Yves here. Some technology enthusiasts predict that as many as 47% of current jobs will be displaced in the next decade. Candidates include not only trucking and bus driving (to be eliminated by self-driving vehicles) but more and more white collar work, as computer get better at the sort of information scanning and analysis that is now done by entry and low-level workers. This post examines different scenarios for how that might play out in Europe.

Of course, the elimination of more and more analytical jobs raises the question of how will professionals learn a craft? This has been a complaint on Slashdot for years, that there are comparatively few entry level information technology jobs in the US, and that we are ceding the IT industry to China and India because we won’t be replacing the current crop of seasoned professionals. What happens when yeoman roles no longer exist.

We also have the problem that economists like to worry about: where do the jobs come from? As we’ve said before, if you have a system in which people must sell their labor as a condition of survival and you don’t provide enough opportunities to do that, you have sown the conditions for revolt.

One bit of cheery news in this post is that, to quote William Gibson, while the future is here, it’s not evenly distributed.

By Jeremy Bowles, an economist at the International Growth Centre, a development economics research centre based at the London School of Economics. Originally published at Bruegel

Who will win and who will lose from the impact of new technology onto old areas of employment? This is a centuries-old question but new literature, which we apply here to the European case, provides some interesting implications.

The key takeaway is this: even though the European policy impetus remains to bolster residually weak employment statistics, there is an important second order concern to consider: technology is likely to dramatically reshape labour markets in the long run and to cause reallocations in the types of skills that the workers of tomorrow will need. To mitigate the risks of this reallocation it is important for our educational system to adapt.

Debates on the macroeconomic implications of new technology divide loosely between the minimalists (who believe little will change) and the maximalists (who believe that everything will).

In the former camp, recent work by Robert Gordon has outlined the hypothesis that we are entering a new era of low economic growth where new technological developments will have less impact than past ones. Against him are the maximalists, like Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, who predict dramatic economic shifts to result from the coming of the ‘Second Machine Age’. They expect a spiralling race between technology and education in the battle for employment which will dramatically reshape the kind of skills required by workers. According to this view, the automation of jobs threatens not just routine tasks with rule-based activities but also, increasingly, jobs defined by pattern recognition and non-routine cognitive tasks.

It is this second camp – those who predict dramatic shifts in employment driven by technological progress – that a recent working paper by Carl Frey and Michael Osborne of Oxford University speaks to, and which has attracted a significant amount of attention. In it, they combine elements from the labour economics literature with techniques from machine learning to estimate how ‘computerisable’ different jobs are. The gist of their approach is to modify the theoretical model of Autor et al. (2003) by identifying three engineering bottlenecks that prevent the automation of given jobs – these are creative intelligence, social intelligence and perception and manipulation tasks. They then classify 702 occupations according to the degree to which these bottlenecks persist. These are bottlenecks which technological advances – including machine learning (ML), developments in artificial intelligence (AI) and mobile robotics (MR) – will find it hard to overcome.

Using these classifications, they estimate the probability (or risk) of computerisation – this means that the job is “potentially automatable over some unspecified number of years, perhaps a decade or two”. Their focus is on “estimating the share of employment that can potentially be substituted by computer capital, from a technological capabilities point of view, over some unspecified number of years.” If a job presents the above engineering bottlenecks strongly then technological advances will have little chance of replacing a human with a computer, whereas if the job involves little creative intelligence, social intelligence or perceptual tasks then there is a much higher probability of ML, AI and MR leading to its computerisation. These risks range from telemarketers (99% risk of computerisation) to recreational therapists (0.28% risk of computerisation).

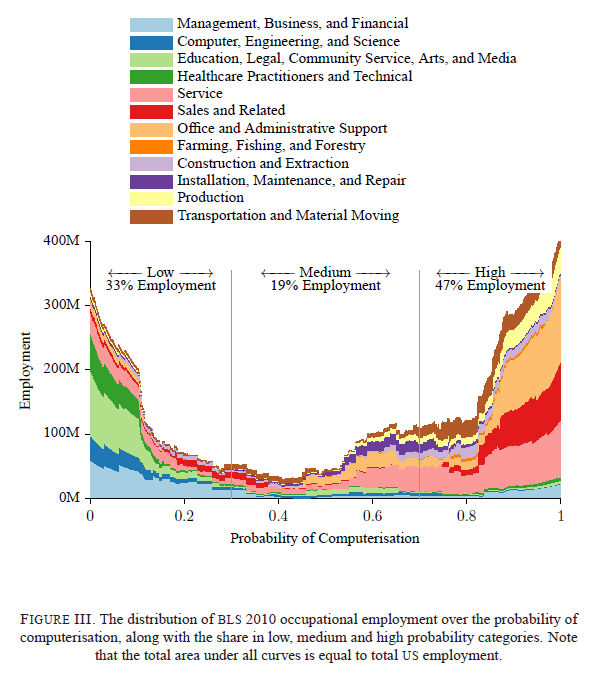

Predictions are fickle and so their results should only be interpreted in a broad, heuristic way (as they also say), but the findings are provocative. Their headline result is that 47% of US jobs are vulnerable to such computerisation (based on jobs currently existing), and their key graph is shown below, where they estimate the probability of computerisation across their 702 jobs mapped onto American sectoral employment data.

How do these risks distribute across different profiles of people? That is, do we witness a threat to high-skilled manufacturing labour as in the 19th century, a ‘hollowing out’ of routine middle-income jobs observed in large parts of the 20th as jobs spread to low-skill service industries, or something else? The authors expect that new advances in technology will primarily damage the low-skill, low-wage end of the labour market as tasks previously hard to computerise in the service sector become vulnerable to technological advance.

Although such predictions are no doubt fragile, the results are certainly suggestive. So what do these findings imply for Europe? Which countries are vulnerable? To answer this, we take their data and apply it to the EU.

At the end of their paper (p57-72) the authors provide a table of all the jobs they classify, that job’s probability of computerisation and the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) code associated with the job. The computerisation risks we use are exactly the same as in their paper but we need to translate them to a different classification system to say anything about European employment. Since the SOC system is not generally used in Europe, for each of these jobs we translated the relevant SOC code into an International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) code, which is the system used by the ILO. (see appendix) This enables us to apply the risks of computerisation Frey & Osborne generate to data on European employment.

Having obtained these risks of computerisation per ISCO job, we combine these with European employment data broken up according to ISCO-defined sectors. This was done using the ILO data which is based on the 2012 EU Labour Force Survey. From this, we generate an overall index of computerisation risk equivalent to the proportion of total employment likely to be challenged significantly by technological advances in the next decade or two across the entirety of EU-28.

It is worth mentioning a significant limitation of the original paper which the authors acknowledge – as individual tasks are made obsolete by technology, this frees up time for workers to perform other tasks and particular job definitions will shift accordingly. It is hard to predict how the jobs of 2014 will look in a decade or two and consequently it should be remembered that the estimates consider how many jobs as currently defined could be replaced by computers over this horizon.

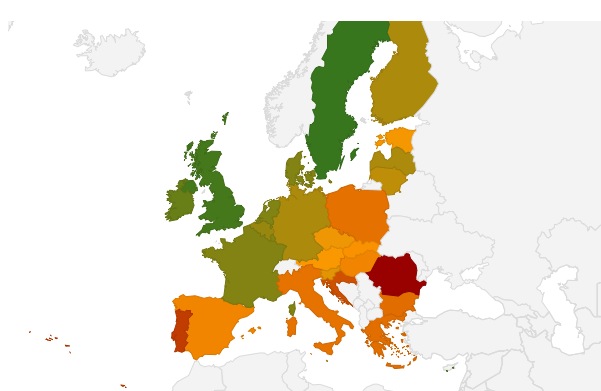

The results are mapped below.

Source: Bruegel calculations based on Frey & Osborne (2013), ILO, EU Labour Force Survey [Yves: the original chart is interactive]

The pattern that emerges is not unsurprising. Northern countries – Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, France, UK, Ireland, and Sweden – have computerisation risk levels similar to the US figure discussed above. The further away from this core the higher the risk of job automation, with countries on the periphery of the EU most at risk.

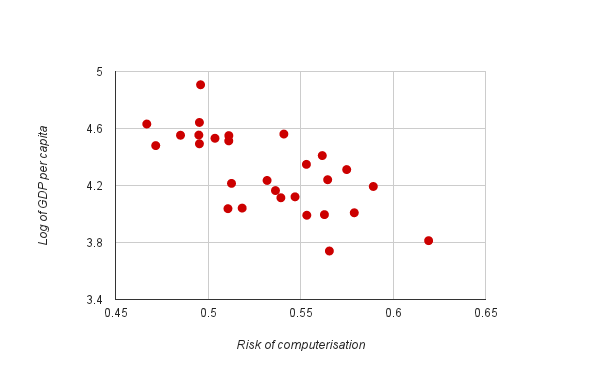

Given the argument that this automation will primarily affect low-skill, low-wage jobs, it is little surprise that the results correlate with other economic indicators. Below, we plot the log of GDP per capita across the EU-28 countries against our calculated risks of job automation, which presents a negative association.

Fig. 3: GDP per person versus the risk of computerisation

Source: As above, Eurostat

This might suggest that the computerisation of jobs is likely to affect the labour markets of peripheral EU countries more severely than northern countries over the same period of time. However, an opposite effect moderates this: peripheral countries have historically adopted new technology more slowly. Due to differences in how fast firms across countries tend to adopt technologies, therefore, it is hard to predict ex ante which countries will be hurt most in a given number of years (since it is hard to know whether lags in technology adoption will outweigh the greater number of vulnerable jobs). Furthermore, the timing of adoption will of course depend on the relative price of the technology. Similarly, the impact and path of future regulation makes it hard to make any statements about the timing of these technological shifts. But in the long term the periphery is more at risk once this adoption occurs.

When, and if, such predictions of technological advance come even close to fruition then the effects will be dramatic – irrespective of geography. Using these estimates generated from the Frey & Osborne paper, they range from around 45% of the labour force being affected to well over 60%.

Though the first order concern in Europe is to tackle persistent unemployment rates, the second order concern of labour allocation cannot be ignored. If we believe that new developments will indeed hit sectors traditionally largely immune to technology towards the low-skill end of the spectrum, then a reallocation of workers towards tasks less susceptible will have to occur. Such tasks are likely to prioritise creative and social intelligence, which implies a substantial challenge in the development of European human capital. Reallocating workers in this way is a prospectively painful process and it seems evident that education systems will have to adapt to meet this challenge.

Appendix

This translation was done at a fairly crude level – from 702 extremely fine-grained classifications into the 22 more aggregated ISCO job categories for which ILO provides good, recent data for across every EU country. SOC and ISCO classifications are structurally related and so this translation process was relatively simple. The six digit SOC code (e.g. 11-1011 for CEOs) comprises the two digit top-level code classifying the job (11 for managers) with the four digit sub-code describing the exact job type (chief executives). The ILO data we use for Europe is classified according to the two digit top-level ISCO classifications (22 of them) – so they provide employment data on code 11 (managers) in general across Europe rather than especially CEOs. However, different particular jobs in the same cluster should be similarly vulnerable to automation and so we average multiple SOC computerisation risks when translating into one ISCO job category. For example, public relations managers (SOC code 11-2031), CEOs (11-1011) and natural science managers (11-9121) should not especially differ in how vulnerable they are. The task is therefore to take the first two digits from all the SOC classifications in the Frey & Osborne dataset and to find its equivalence in the ILO ISCO system and to average across multiple jobs where necessary. This aggregation certainly loses a bit of nuance, but given the predictive nature of the data and the above point about very similar jobs within each of the 22 classifications, this seemed a reasonable solution.

“As we’ve said before, if you have a system in which people must sell their labor as a condition of survival and you don’t provide enough opportunities to do that, you have sown the conditions for revolt.”

A very appropriate TED talk: http://www.ted.com/talks/michael_sandel_why_we_shouldn_t_trust_markets_with_our_civic_life

Any society that forces people to participate it markets to meet their basic living needs is a “society” that doesn’t deserve to exist. Nor will it, for especially long. It’s a peculiar disease of implicit American thinking that all living needs must be met through the commercial/market economy, which leads to all sorts of bizarre cognitive errors among those so afflicted. The silver lining is that those who persist in living with such a warped ideology will eliminate themselves from the gene pool in due course; the downside being that they’ll likely take a lot of innocent people and ecological systems with them on their way out.

It can be speculated that this mentality comes from the idea that ones proximity to god can be measured in how well one do in life. So if you fail to find work and end up starving, you are distant from god. But if you do well and collect riches, you are close to god. This independent of how your fellow man judge the actions you took to collect those riches…

This was a brilliant observation!

The historical process of forcing the peasantry off the commons and into the capitalist market system is described in “The Invention of Capitalism” by Michael Perelman. It’s called “primitive accumulation” or “accumulation by dispossession;” also related is “enclosure of the commons.” The nobility, many of whom were members of the law-making body, Parliament, gained legal ownership of the common lands (today, this is called “public land” or “public space”) that had been the peasantry’s ancestral homes and farmland. Consequently, the landless peasantry, who in the past operated their own farmsteads, migrated to the cities where they became the “wage slaves” whose labor, along with steam-powered technology, powered the factories and produced the enormous profits of the Industrial Revolution. The classical political economists said that the laborers supplied their labor voluntarily at subsistence wages in response to the “silent compulsion of the market,” i.e., to avoid starvation and homelessness.

The kind of “full time” work that most of us associate with “capitalism” is quite a recent invention. But its running into a limit to that in that technology is improving exponentially faster and faster, because the more we learn, the still more we learn faster.

So we have to keep increasing the skill level or accept that large numbers of people will rapidly become unemployed if we don’t. There won’t be a twenty or thirty year long period to adjust during which humans will still be working and making enough money to buy the consumer goods of industry. The window of opportunity during which we can pull our society up to meet the challenge is rapidly vanishing.

To the people who seem to have an idea that these changes are hypothetical or that the technology isn’t there yet, I would like to say, we don’t need any new technology to do all this, it already exists.

So everybody would be wise to strongly encourage a re-shifting of society’s priorities or else we’re committing economic and political suicide.

If they can’t let go of the death grip, our “elites” failure to accept what’s happening and be honest about it will threaten the survival of the whole planet.

I don’t see much in the way of improvement, to be honest. I see change for the sake of change, I see computing technology from decades ago rehashed, I see more space made for tollbooths and coin boxes and gratuitous hassles that can be turned off at the flip of a switch, for a price. The natural world, itself, doesn’t change much.

I want to live in a society, not a video game. The hamster wheel does not need to spin ever faster to help people eat. In fact, effort spent in competition is taken away from eating and being left the hell alone.

https://www.google.com/search?q=%22there's+an+app+for+that%22&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ei=ILnJU9ywDvPmsATHnYDACA&ved=0CC0QsAQ&biw=1280&bih=598

The one technology that will free workers to do other jobs is to replace the spreadsheet with other online systems. There are no layoffs but will allow teams to be more efficient.

I like spreadsheets, and they help me do my (IT) job. So I guess I don’t get why you think they’re such a hindrance.

As always, the unasked question is why jobs, a very modern invention, have become a must, an imperative. As jgordon implies, it’s not some biological/psychological necessity that humans exchange ‘work’ for money to meet their basic needs, it’s more like a value distortion. Discussion of this old technological unemployment dilemma should not be reduced only to one of full employment versus the horrors of unemployment, it should include how society defines value, what meaningful work is, what reward and success are, and other fundamental issues of that nature. All these issues should be on the table.

We are not and there is no such thing as homo economicus, mainstream economics is in deep error on this point (among many others). Nor does consumerism work in terms of emotional and psychological health. Perpetual economic growth is impossible. And so on and so on.

I suspect part of the answer can be found in the width of the term “work”.

It can encompass any activity that involve the body in shaping something else.

Thus it produce mental images of someone tilling the soil, or someone attaching pieces of something onto a larger whole.

Both things are “work”, but one is more directly related to survival than the other.

Very generically, it’s difficult to think of a single activity that is not work. So the question is about defining activities that society values at some level, then how to go about enshrining/honouring/rewarding/promoting them. E.g.: Why is sleep not work? Imagine how unproductive we would be if we were all wholly sleep deprived, but how do we pay people to sleep? Same equation for fun and joy. Housework is valued by society, but not by markets unless you pay someone to do it.

Right now market processes do much our thinking for us (what is the value of planet earth?), so most of what cannot be measured by those processes is in effect losing value and power.

Another part of this is of course defining productivity. Producing what in what way and for what reason? Consumer goods for endless and meaningless consumption to hell with the environment? Or peace, health, and well-being for reasons of community and environment?

Why should things the market can value be more valuable than things it cannot? Probably because the market is systemically required to grow so has kind of taken over, and because at a deeper level we are more or less obsessed and addicted to the ‘science’ of valuing the measurable over the immeasurable…

A hypothetical future society within which most work that resembled today’s work was automated would not be lacking work, its just that the “work” done by many people would probably look a lot like the work done by people who really like what they do today. Not coincidentally, many of them are also quite good at whet they do and are paid well for it. One really has to like what you do to become a real expert at it. Money alone wont get you there. You need “flow”. Or altruism.

Scientists doing research often (to me) seem to largely do what they do for reasons other than money. They often are so focused on their work that money is less a ruling force in their lives than it often is with most others.

Also, consider the huge amount of time which people spend at the most repetitive or soul-crushing jobs which in most cases is wasted time.

If instead they spent more of that time learning, or with their families, lots of new areas of work would emerge out of that time, and more economic activity would be able to take the place of what we no longer need to do.

By focusing on the jobs lost, instead of the huge gift of time, we’re not seeing the forest for the trees.

If the caveman lived in a hot region, he could probably take more naps that if he lived in a cold region.

This whole article seems to be based on the strange presupposition that there is a fixed amount of jobs. If this was true, we would have hit permanent 80% unemployment once we industrialized agriculture. Now, it is true that entry level jobs are harder to come by but the same can be said of all jobs as our countries have developed. An illiterate, barefooted peasant would struggle to get a job in modern economy.

The solutions to these problems are the same as they have always been. Education, training, internships, possibly with govenrment subsidies, increases in aggregate demand and protectionist measures when appropriate.

Additionally, technology may work to centralize power and wealth. However, as long as there is no affordable, easily maintained robot infantry, the state is perfectly capable of redistributing wealth and power. The only question is who has the power over the state.

Really concise comment. I would add to this that strong environmental protectionist measures with effective enforcement also work to fight centralization of power and wealth. NC Readers are already familiar with this logic from the financial sector, but it’s much more widely applicable.

I work in the automotive industry, and things like the Euro VI emission standards or SAE J2464 crash safety standards for electric vehicle battery packs mean that more people need to be employed to build the products, but the result is improved health and safety measures for everyone.

The fact that we’re heading towards environmental disaster while a huge percentage of human brain power stands in the unemployment line would be darkly comedic to the outside observer.

Have you looked at the kind of “busy work” that has sprung up over the years?

Telemarketing, anyone?

More and more “work” seems to involve some kind of paid social interaction with other humans, even if those other human beings do not want the interaction.

Also, unsustainable use of “short term” credit has ballooned.

Gresham’s dynamic: when suffering can be compensated, eventually only suffering will be compensated.

All of those kinds of jobs are truly horrible jobs, and additionally, they are vanishing. People who think that if they lose their current job, they will just be able to get another one at lower pay don’t grasp the situation. What’s going to happen is that a larger and larger segment of society just wont be needed to work at all, for anything. Not because they wont be able to do anything better than a computer. Sure, they will still be able to do a few things better than most computers. And jobs will exist that require that kind of work, somewhere. However, numerically, those jobs will be far far fewer than today. They will pay little, because the supply of workers will be so great, and they will be taken by others who are better connected or younger or more attractive or better able to present themselves, or most likely, simply in another part of the planet.

Look at the situation of economic hopelessness faced by people in parts of the world where there simply are few jobs and imagine that lack of economic opportunity was the norm for the entire planet, and you’ll see the effect of failing to meet the challenge to give people more free tme and more access to education.. Business will not be able to sell their products, we will have have a world filled with poor people with no educational opportunities, and no adequate means of survival, existing on the edge of survival, if that.

Here in the US, we spend a lot of effort on reinforcing hierarchy that we should be devoting to growing wiser. We’re getting left behind as we waste years of precious time arguing and pouring endless resources into the black hole of spying on one another instead of learning.

Meanwhile, much of the rest of the developed world is spending more of that money much more intelligently, and compared to us, moving forward. Rather than trying to drag them down to our level (i.e. TTIP, TPP, TiSA) we should be rising to meet the challenges, together. Its not a zero sum game. We can all “win”.

Slashdot mentioned on Naked Capitalim?!

Yes I look at it most days when the news isn’t overwhelming, as it has been of late (Ukraine, Gaza…:-( )

Heh, maybe i should get back into the habit. Used keep an eye on the site until ol’ Cap left.

A 2nd Machine Age implicity relies on the notion that artificial intelligence is an actuality. Unfortunately, for pie in the sky computer scientists with their atheist religion of the “singularity,” AI is a long way off, if even a possibility. Computation is not thinking, no matter how much those self-diagnosed on the autism spectrum want it to be. If you don’t believe me, play any computer game produced in the last year, and eventually you will figure out the AI, no matter how good it is. And most game AI is cutting edge compared to nonsense like Siri.

I currently work as a machinist, cutting metal parts for industry using CNC machines. You will not have a robot as adaptive and as facile as the dumbest human working in a machine shop. Pure and complete automation is a pipe dream of techno fantasists who’ve never really made anything beyond code (and tchotkes with their 3d printers, though milling thermoplastic is still many orders of magnitude faster). And given how glorious software products and algorithms have been at improving our lives is further evidence that the 2nd Machine Age is not some inevitability.

For AI to happen, there has to be a serious theory of consciousness in my humble opinion as a mathematical physics dilettante. And I agree with Roger Penrose that consiousness won’t be understsood until there is a decent theory of quantum gravity, something that many, many hyper-intelligent theoreticians over the decades have yet to even create a testable hypothesis (you know, people like Einstein). And I don’t think that consciousness is something that is “emergent” from the “processing” done by brains considering that observation in effect makes reality on the quantum level (ie collapsing the wave-function via measurement). But again, I’m just an auto-didact who has struggled with smoking over the years, too stupid to know better (yes this is a rhetorical device being used to persuade you).

The heavy use of computer metaphors to describe the brain, mind, and psychology (like wired, processing, circuits, etc.) has done a great disservice to our understanding of consciousness. Mind is not a computer. A greatest neuroscientists can’t tell us the appropiate level of neurotransmitters needed to have a “normalized” consciousness, because they cannot measure the levels of serotonin, dopamine, anadamine (yes I’m a pothead, so I have to give props to the endo-cannabinoid ‘system.’ Smoke weed everyday children), and measurement is fundamental to science (and machining). Mind, consciousness, thinking, imagination are still very much mysteries to science, and the absurdity of a bunch of socially inept nerds creating an actual model of mind, blows my mind, and not in a good way.

Machines will get better a making things, or generally the how, thanks to the computational power afforded by cheap computers, but not the why.

Ultimately, papers like this ignore the crucial questions of epistemology that are raised by assumptions that have no merit or reality to them (not in economics, the most humblebrag of pseudosciences). More mental masturbation by economists, “professionals”I would gladly see replaced by machines, because if they were machines we could unplug them, let their batteries die, or throw water on them and short them out (ala the wicked witch of the west, I suppose). But I’m just a grease monkey not aware of anything more than the metal chips in my boots.

Bingo!

AI bumps up against Kurt Godel. The perception of AI is limited to the symbols it is programed a priori to recognize. There is no algorithm to generate new symbols from unanticipated data which can then be incorporated into its corpus of knowledge to expand its perception. AI is fundamentally based on axiomatic systems, and Godel has already shown us that axiomatic systems intrinsically cannot jump out of themselves.

Forget computers. The computer revolution will be superseded by the coming, truly spectacular revolution of synthetic biology. It is there we will see all the limits break down.

AI pushed to its limit will be some form of water based living organism and not metal and plastic-based?

What the commenter is referring to is not a materials problem or even a technology problem, but a basic theoretical one, introduced by Heidegger but made relevant to questions of the computational model of the mind, still ascendant, oddly, in the social sciences, by Hubert Dreyfus: that epistemology (how we know) cannot be meaningfully divorced from ontology (what we are). AI presupposes that the how of thinking can be separated out and reinstated in some other, as computer engineers would say, platform for which the mind, according to this theoretical construct, is mere programming. For those not familiar with Heigedder, the problem with a computational model of the mind is this: our understanding of the world and our being in the world are not a simple function of stimulus and response but of interpretation. In other words, what we are and, more importantly, how we understand ourselves as being at all only works within the context of a constant process of engaging with the world and revising our understanding of it in relational terms. It’s more complicated than that, of course, but that’s the basic problem.

AI isn’t necessary for technology to have a huge impact on employment. All thats needed is what we have now, fast networks at low cost. Since there is a large wage gradient from one area to another, if I want “AI”, cheap, all I do is set up a fast network link and hire some humans on the other end of it, to do the job here.. poof: “AI” – One form of that is what’s called a “telepresence robot”

AI is to consciousness what conjuring is to magic.

Thank you. Great comment, and loved the last paragraph

Isn’t it ironic that the type of work you do creates the wealth that the banksters and economists extract for themselves?

‘Smoke weed everyday children.’

This seemingly casual remark actually constitutes a Toker Turing Test: human intelligences can get high and step outside themselves; artificial intelligences cannot.

I still think a Turing test can someday be faked without actual consciousness. I’d really sit up and take notice if a computer picked up a small rock and threw it at a dog for no reason it could articulate, and then reports being oddly satisfied by the yelp – sort of like a young boy would do.

Do you think the “maker” movement is impacting your business, say, people being able to go to a (member supported) “hackerspace” where they have access to things like CNC machines (and other expensive specialized tools) – at low cost- when they need them?

Frankly no. I work on a precision lathe that cost 600K and has a 19ft bed. Makerspaces don’t do much production, just one-offs and prototypes. Real capital (oil, aerospace, shipbuilding, etc) requires huge machines and tools to do what they do. And that’s where the money is at in machining. The one makerspace I checked out in my area was a bunch of guys making tchotkes and small tools. The makerspaces might be competitive with small shops that do custom work (auto parts, cabinetry, etc.) but again it’s computer dudes competing with guys who have years and years of experience doing these particular things.

And 3d printing, while very cool, is very slow compared to using a mill or a lathe to the same thing. And metal 3d printers are very expensive and not as precise as a good mill.

Milquetoast, having spent a good amount of time inside a tooling shop (and having even taken some baby steps turning the wheels of a manual Bridgeport under the tutelage of my pot-smoking buddy) I like the cut of your jib. I shall raise a toast to you at 4:20pm local time.

It is unfortunate that the 3-D printing/Arduino/CNC True Believers (and I have many of them in my local circles) don’t often nurture the mindset of dealing with turning things one can drop on their foot into other things one can drop onto their foot. They seem to prefer birthing things from their foreheads like Zeus and not getting their hands dirty except on a special occasion when they might buy a kit — the line between makers and consumers blurs every day. I suspect that attitude is a matter of bobo class identity as much as anything. That said, there are makerspaces which have real live manual machine tools available for use (there has never been a better time to take industry’s castoffs) and their members seem to have a bit more appreciation for ways of making things that aren’t simply developing intricate procedures for the robot help. Those shops are the ones that design and build their own robots. One near me was working on building a large CNC plasma cutter when I last dropped in, which I respect, even if they weren’t in the habit of designing high-voltage power supplies for themselves.

Not that microcontrollers aren’t amazingly useful and wonderful and quite an efficient way to do some things, but in today’s consumer market they inevitably seem to be found gossiping amongst one another about their owners, often behind their owners’ backs, instead of doing what they were retained to do. Now that the Internet of Things is sold as a feature and not a bug, that only promises to get worse.

It’s telling that, as a society, we have branded the ability to perform vaguely specified tasks with a modest degree of independence at the demand of another “intelligence”, isn’t it? Worse, that we have chosen to lobotomize “intelligence” such that we get Comcast call center jockeys trained to fail a Turing test much like the rest of the company. True intelligence (by which I mean conformance to *my* beliefs) would be telling users to p— up a rope, in the most creative way possible, and I don’t see much demand for AIs doing that (except maybe in entertainment).

Hahaha. Indeed.

Hoinestly the guys that impress me the most in the machining world are the old dudes who’ve been doing this stuff for 30+ years. I’ve been fortunate to be trained by a fellow who grew up in a machine shop, and has almost consistently worked in one for the last 40 years. You can write programs and work out the maths for things, but a real machinist has to fix a $50K tool that’s been messed up beyond recognition and yet keep it all in spec. A good portion time is spent grinding and re-working the metal so I can cover up cracking and pitting. There’s really an art to it, and you learn that art by doing it every day.

Coding is cool and very useful, but with a program you get an infinite amount of times to work out the bugs. Not so much with machining.

AI doesn’t have to exist for enormous amounts of labor displacement. In a pharmacy, techs could run all the ancillary services, while the pharmacist is in a call center using a webcam to verify drug interactions and counseling. This would eliminate 30 percent of the pharmacists for the same number of pharmacy technician jobs. The google car is hyped–I’m sure they can’t get it to work in bad weather, bad roads, lot’s of traffic, pedestrians, etc., but google may lobby the government to change the road systems to meet its ability.

Yes, service would decline and mistakes would increase, but this could be remedied with increased savings by labor displacement. The same with waiters. They may have a proper robot that can walk and move doors, pick up glasses in 30 years. It would still have worse service, but the bosses may see a marginal profit increase with which to roll into financial instruments, further eroding the ability of the system to create goods and services.

When I was a kid, I remember that the scared tales of completely automatized factories with just one worker: the robot operator. Now, iPhones are assembled by hand. Go figure.

According to Rifkin in “The End of Work” (written in the 90s if memory serves) there are “lights-out factories” in Japan. Factories that need no lights because no humans work in them. Of course there’s administration and maintenance, but you get my point. Much can and has been automated, and more still will be.

IMO, this is not about full automation of everything OR full employment. It’s not that stark a binary. We have to include environmental resilience and carrying capacity, energy, machine-based productivity, the limitations of monoculture farming, the emptiness of consumerism, the worship of the market, the vacuity of most mainstream economics, the legacy of protestantism, etc. etc. etc. I.e., because perpetual growth is impossible, because automation is only going to improve (regardless of how attainable full AI is), because jobs per se do not make humans happy (meaningful work/contribution and fun and joy etc. do), because healthy communities are important etc., we need a far deeper discussion on the whole direction of western civilisation. And I think that discussion is taking place. Here I am contributing to it!

Often overlooked in the myths of our robot overlords is the logistical problem automating so much creates. All these machines require a great deal of energy, rather rare minerals, and a network infrastructure that requires constant maintenance. And if you automate the maintenance, you actually exacerbate the aforementioned concerns.

with 1 million employees they are looking at over 100,000 robots very soon (IPhone 6) at $25,000 each

so the hand made you speak to will be gone shortly:

Foxconn committed to building and using 1 million custom-made robots, dubbed “Foxbots” to help offset rising human labor costs. In a 2013 financial report, Hon Hai Precision noted:

“To remain cost competitive, we have been continuously controlling manufacturing overhead to attain better operating leverage and improving efficiency and yield

rate through automation using robot arms and industrial engineering methods like production cell management.”

By 2011, the company had reportedly rolled out roughly 10,000 robots, though, by most accounts, they were capable of only the most menial tasks and could not build an entire product by hand (er, robot hands, that is). As of last year the company still hadn’t found a place for all the robots it built.

Electronics manufacturing uses a lot of automation.

Did this report mention any of the new job categories that will appear in the next 20 years? Just because we can’t imagine them now doesn’t mean they won’t exist. How many website designers were there 20 years ago?

Call me a skeptic, but I don’t think we will be replacing truck and bus drivers in even 30 years. We’ve had autopilots that can take off, fly the plane, and land for 30 years already, and that problem-space is orders of magnitude simpler than driving a bus. They still put pilots on planes because they are vastly superior at preventing catastrophic loss of control.

Google still puts a person in their “driverless” cars as they tool around and I doubt they are in a hurry to release an honest report on the number of interventions needed by the drivers.

There’s also that moral problem the vehicles have to overcome. In a pinch, should the vehicle run over the little girl or the dog?

I’ve seen a lot of news articles that list this but it always seemed like a bizarre thing to focus on. How often does a situation like this actually come up? The real problem is that it’s going to get stuck in environments that require judgment calls simple for human drivers.

How do you program a vehicle to handle a huge variety of pedestrian-heavy areas like arenas, schools, or construction zones? What does it do if something blocks the road? Automated driving on a test track is an absolutely trivial engineering problem and most of the equipment for optimizing performance is already commercially available. Reliability, security, and interoperability in the real world are huge obstacles.

You are exactly right. I guess I was using the moral problem to show that completely autonomous driving is not really a computable problem.

It’s a bit of a hype machine. Remember when Siri was supposed to change everything? I asked Siri where the first occurrence of 77 sevens in a row during the expansion of pi can be found, and she didn’t have a clue. She couldn’t even tell be how many times someone asked her that question before, or even how many driver’s licenses were issued in Hawaii last year.

Keith, I’ve ridden in autonomous cars. The technology is are advancing very quickly.

We already have autonomous vehicles on our roads in some areas. We’re going to have autonomous vehicles on most of our roads within a few years. The financial incentive to do this is huge. It will happen.

In probably less than ten years, in large parts of the world, autonomous trucks will be delivering packages to a box of some kind next to, or perhaps – at people’s doors. And that will be routine.

Why is the financial incentive huge? The way I figure it, Google has to add $70,000 worth of equipment to each car (not to mention the compute and mapping resources outside the car), and they still need at least one person in the car.

Ten years from now, I feel very strongly they will still need a driver to prevent catastrophic loss of control and to negotiate non-computational situations.

Google cars rely on micro-mapping the route. If there is construction, or an accident on the highway with one lane having to merge into another, bumper to bumper, then a car without a driver will sit there until it runs out of energy. The way we merge now is to nudge out, to make eye contact, to show a willingness to risk accident, to fight our way into the lane of moving traffic. That is non-computational and requires a person.

They also have a huge loss-of-communication problem. If they manage to solve the problem of reliable communications in all conditions, then they should share it with cell phones. Out-of-area means loss of control.

That’s my current thinking. I’ve been wrong before. I believe paying a driver $10 bucks an hour will still be the most economical and least dangerous way for many, many years to come.

This is a good point, I see it as more of a spectrum. Some features on the road to automation are obvious wins for say, a commercial fleet owner. Lane control or an automatic gearbox means less specialized drivers can be hired at a lower wage without a huge vehicle cost increase, but the last steps towards replacing a minimum wage driver with a machine become incredibly expensive.

Google is doing all this research, they say, because of the extra hour or two a day of web surfing they figure people will do while riding to and from work.

But, there are probably other reasons, too.

There are teams all around the world working on autonomous vehicles. The DARPA “GrandChallenge” events give them a chance to square off against one another on various kinds of courses.. desert, semi-urban, etc. Its worth looking at them to get an idea of what goes into the technology. Lots and lots of different pieces all working together.

I agree, they are not all the way there yet. But I think they will be, within a few years.

I can say with certainty that 10 years is a bogus timetable for full automation, particularly in the trucking industry which is very conservative about introducing new technologies. Do you know what the development timeline is like for a new Class 7-8 Heavy Vehicle? How many trucks even use LED lighting? How many hybrid or fully electric trucks are even on the road now? Read Navigant Research’s summary on their predictions for hybrid truck market penetration if you want to see how fast that industry moves.

High levels of autonomy in different scenarios (highway, traffic jams, maybe rural roads) could be commercialized in 10 years, especially for passenger cars, but there are a million things that have yet to happen both technologically and legally before someone is ready to sell a fully automated car.

I’d like to see how that autonomous car could do getting in/out of a stadium parking garage.

>I’d like to see how that autonomous car could do getting in/out of a stadium parking garage.

They would probably consult a sort of online machine readable map which contained the shape of the garage without any cars in it and then match it with the realtime lidar data. Also, they would probably use machine vision to tell them generally what was a car or truck and which direction it was pointed, what the lights were indicating it would do, etc. That would tell them about what a regular driver knows. Although there are a million situations that aren’t in the database, I’m sure.

You’re right, its going to be a long time before they get it ALL sorted out.

Do people know that most air travel uses autopilots most of the time now?

The WWW has helped a lot of businesses become much more productive by enabling them to serve customers 24/7, regardless of where they are on the planet. But, lots of areas still aren’t able to take advantage of them, and for many things, like food, or oftentimes, clothing, buying in person is preferable.

We will always still need people to do xyz, somewhere. Just fewer and fewer of them.

The adoption of new technologies, is occurring more and more rapidly.

Actually, my high school employed a driver education teacher in high school who was known to matter-of-factly present such morbid dilemmas regularly to his students.

As for website designers, perhaps a hundred. But I think that’s the wrong question. Is working 60 hours a week fighting the ever-rotating platforms created by bourgies on the West Coast for some hard-nosed small businessperson, *living*, or even *production*, really? No, it’s social grooming, at best, just like most employment.

While this is a clear aggravation, the tendency to destroy jobs via mechanization has always existed in Capitalism. One could mention the Luddites or Marx’ example of the pins manufacture, but maybe the best reference is Marx’ son in-law, founder of the Spanish and French Socialist parties and first ever French Socialist MP, Paul Lafargue, who has been sadly enough forgotten by most. In his main book, “The Right to Be Lazy”, he already advocated (100 years ago!) for 5 hour journeys and a society of leisure, because he realized well that much work was socially useless and that work distribution was a necessary step for the overcoming of the current condition of Humankind, something clearly facilitated by Capitalist technological development.

While the appearances are often of struggle “for the right to work”, in fact the core of class struggle is the need to reduce actual work, which has two possible outcomes: (1) to dump masses of low qualification workers into misery, ghettoization and social discredit, destroying aggregate demand in the process, or (2) effectively distribute work while qualifying the workers to do the job that is actually needed, what is indeed a Socialist approach and has no room under Capitalist conditions, as it requires social equality and planning.

However, Capitalism seems unable in most cases to sustain the demand, precisely because it is unable to guarantee employment, so the social contradictions, but also the purely economic ones, are clearly building up very fast. Only a rapidly shrinking “select club” of economically core countries seem able to keep up with the draconian demands of this Wildest Capitalism that rejects even the Keynesian patching strategies directed to keep demand relatively high.

The outcome seems obvious (growing crisis) but the exact details of this civilizational junction are unknown and, as of today, there is great danger of fall-back into fascist barbarism, which is no solution in any way… unless they plan to gas every single pauper.

While the whole of human kind argues that there is enough for everyone and that we should minimize work and maximize leisure, the workaholic power hungry seize the core assets that control the discretionary.

Hunger for power and work ethic – are they related?

It seems to me that Thorstein Veblen’s observations about “the theory of the leisure class”, (written in 1899) still hold up surprisingly well! (its worth reading if you haven’t already, its free on the web)

But he was writing before the late 20th century tech explosion..he is more accurate if you ignore high tech wealth. There, the competitive ethic is strong.

Isn’t more pertinent/illuminating to say that capitalism created the idea of the job?

Isn’t more helpful to examine how we might get away from our dependency on paid ‘work’ in pursuit of a more humane and environmentally-aware system?

Well, they needed armies of workers to man the machines of industry, which represented such large investments they would be run almost continuously.

When my grandmother was a child, she had to unstitch her hand-me-down worn out dresses and re-sew them on the other side. In those days, standards of living were close enough for the same jobs across the planet… apart from the 1%. She is still alive today and living proof that this was not so long ago.

The problems we are encountering today are due to unsustainably large discrepancies in living standards between developed and emerging markets. Until the standards of living are more equalized across the planet, I don’t see how our current problems will get solved. In my mind, we are in the first innings of the equalization process. And since our Western economies are primarily based on materialism, it will hit hard.

What do you think about TiSA?

Would you give up your job so that some family in a developed country can have a member working far away for half of what you make, the existence of this “agreement” giving US multinational-corporations the “right” to be seen as a local supplier – and say, build a factory in India or Malaysia or some such?

>The problems we are encountering today are due to unsustainably large discrepancies in living standards between developed and emerging markets.

I think it’s horrible but I also think we’ve hit a point of no return. The whole planet can not live like Americans… so either America becomes protectionist and to hell with the ROW or current American wealth gets redistributed globally.

Just like water finds the path of least resistance, so will wealth.

Discussions of the future like this one, which do not mention global warming, peak oil, peak water, peak soil and so on, make me crazy. Short term — for decades or maybe centuries — there is going to be plenty of work, changing how everything on the planet is done. Some of it may be done by robots, but a lot of it is going to be done by people. Alternatively, the problem of excess labor will disappear, because most of the human population will die, leaving (as one climate scientist has suggested) a few thousand people living in Antarctica. These people may be served by machines. Not our problem. We’ll be dead.

Sure, there will be work, but, (playing the devils advocate here) since the price of bandwidth is approaching zero, say, if I want somebody to do it, if I am willing to have them work remotely, I’ll be able to hire somebody for a lot less.

For physical jobs, maybe use a “telepresence robot”.

Point being, you cannot extrapolate one thing into the future. There are a whole huge range of technological, social, environmental trends, all of which work together to make the future. This is why writing science fiction is so hard. I’d say, for example, that the problem for the southern European countries is not automation, but that fact that they are currently being destroyed by EU economic policy and — slightly longer term — they are likely to turn into deserts.

There is a lot to be said for a society that allows people to move in and out of the work force at will, and supplies an infrastructure that makes it easy for people to devote significant chunks of their lives to learning – experientially, skills which will help push them, and by extension, all of society ahead. Otherwise, the race to the bottom quality of ever improving productivity, increased supply and decreased demand will throw the world into a downward spiral – an economic implosion of the whole planet. It actually makes sense to pay people to drop out and work on personal improvement or projects for some percentage of the time, however.. they are working to make ideas like that impossible to realize by means of these horrible free trade agreements. How many people here realize just how far they reach into our lives and future, I doubt if many of us do at all. let me give you some examples.

#1 thing we need to do – the most important thing that we could do to prevent families from economic disaster – is single payer health care- which saves about half of every health care dollar and allows all doctors (all doctors are in network) to be paid significantly more. However, the US primarily, is busy outlawing the things that would be necessary prerequisites to single payer, internationally, irreversibly, in TTIP,TiSA, and TPP. What could be worse for our people’s future economic security than that? Nothing.

#2 thing we need is more public services, especially free education. Same as 1, the US, primarily, is trying to permanently, irreversibly eliminate the entire global spectrum of public services, and prohibit the creation of any new ones, in countries that want to trade with the US, again by means of FTAs.

Okay, the #3 thing we need is to encourage a new kind of employment that prevents people from falling off the economic map as the previous work world shifts into the new one, which will directly employ far fewer people in today’s professions, giving them a bridge to learn the skills tomorrows professions will demand, which will often take years or decades..

We need to accept that there is a huge need to pay people to do things which are not immediately profitable for some company, as a learning experience. We will also need to for example, build infrastructure to replace our decaying infrastructure. many people assume that that process would also create jobs for Americans, however, think again, it wont, not if TiSA is passed.. The effect of the TiSA ban on discriminating against foreign firms in services procurement will be to prevent infrastructure from being rebuilt except in the most dire of circumstances, which will have a chilling effect on the entire economy.

We cannot expect governments to pay people from other countries to rebuild infrastructure as that won’t improve the employment problem here.. Remember the WPA, the product of the Depression make work programs? Well, the WPA would be outlawed as discriminatory. By TiSA. that is insanity.

Why do we run into the same as 1 and 2, why are they are trying to make every simple solution FTA-illegal?

What else do we need? I have a feeling that somewhere in TiSA, TTIP, or TPP, or the existing FTAs like GATS, they already have, or are working on a way to make whatever that necessary change is, impossible! Secretly.

Why, can anybody explain why?

Guy Standing, a British economist who worked at the ILO for 30 years and quite with criticisms of that institution’s lack of insights into the problems that labor faces in the 21st C., just published a new book “A Precariat Charter” which is reviewed extensively here -> http://righttobelazy.com/blog/2014/07/%E2%80%9Cthe-proletariat-is-dead-long-live-the-precariat%E2%80%9D-2/

Thanks for the link! I found this paragraph, towards the end of the review, especially thought-provoking:

“Here in the US we have less certainty about the political power of our indigenous precariat. While the lack of a conscious precariat network of rebellious participants as exists in Europe must be considered a major drawback, no one can deny that in the past few years the working poor have waged a very combative grassroots fight. Whether they can develop the autonomy that they will need to take their fight to the terrain that A Precariat Charter depicts, is uncertain. One thing is certain though, no social change of any significance will occur without a new class struggle.”

My experience working with fast-food and retail workers gives me real hope that this struggle is about to begin in earnest.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hAOxWHeJq2Q

Strikes don’t address the fact that restaurant automation is moving forward very rapidly. We really don’t have an answer to the rapid, global elimination of low skill jobs. Its a mistake to try to prevent automation. What we need to do is get society to face the fact that the old jobs are going away and that the new jobs require a much more comprehensive set of skills, which can’t be taught in a year or two.

We should be attempting to get society to understand its not some 20 or 30 year away problem. Its here now. And nobody knows how to solve it, we need to put our heads together and figure out a solution which respects all of society’s rights to dignity and opportunity.

Why jobs?

What do you mean?

Most of these new jobs wouldn’t require such “new skills” if the fashionable children of the Valley would stop making up ten new incompatible APIs every year for social cream puff toasting or whatever. Three would suffice. There is no intrinsic need for technology to advance so quickly and so disposably, and there is a very good case to be made for slowing the pace down based on the way we’ve managed to pervert nearly every new technology created over the past century or more to grim, dismal ends.

So, with all the time just freed up from obsession-compulsion, what do we do? When the robot overlords have reduced the amount of labor necessary to, say, 10000 hours for a lifetime (down from 100000), do we all retire at 30? How do we allocate the little bit of work that must be done? How do we accommodate with dignity those who don’t care to ride the hamster wheel for greater glory and provide some kind of Grand Project by way of a useless but safe game for those who do?

Like Paul Lafargue, I don’t think working *more* gives me anything I want, and I’d appreciate not being coerced into these hare-brained, ridiculous schemes by way of withholding food and shelter.

Since our economic models do not account for externalities, a lot of these machines are uneconomic but we don’t know it yet.

Just think of all the energy that is consumed when you realize you are kissing one egg, hop into your car and drive 5 km to just get that. Our whole economic system is based on this gross misallocation of resources. All these machines that get developed and produced are based on the same inefficient and flawed models.

At one point, trues costs will start to pop into our models and force an incredible realignment. Just go take a look at the balance sheets of the top 10 discretionary companies. They are running on fumes generated by financial engineering.

I believe we are at a societal peak in discretionary spending and useless waste of energy of resources. These will be forced into the maintenance or rebuilding of essentials.

I find it interesting that there are people who think truckers and bus drivers jobs are in danger. The railroad still hasn’t managed to create remote operated trains that don’t require people to operate them. Why in the word would anyone think that it would be easier to do this with roads when it hasn’t been done with tracks( or trains with equipment that allows the railroads to monitor them) successfully?

I’m still weighing in on the side of folks worrying that the sky is falling in terms of being replaced by technology. Some jobs will disappear, others will emerge, just like it has done for centuries(that’s why you don’t see blacksmiths and milkmen)

So really in a nutshell everything is going to plan…!

Viewed from the position of the Illuminati ….!