Yves here. Although the case study is the UK, this post is yet another example of how counterproductive austerity is, from both an economic and a social perspective.

By John Weeks, an economist and Professor Emeritus of the School of Oriental and African Studies of the University of London. Originally published at Triple Crisis

This post is a selection from a longer report on the state of the UK economy, “The Cracks Begin to Show: A Review of the UK Economy in 2015,” by Economists for Rational Economic Policies (EREP), kindly sent to us by occasional Triple Crisis contributor and EREP co-convenor John Weeks. The full report, whose contributors include Weeks, Ann Pettifor, Richard Murphy, Özlem Onaran, Jeremy Smith, Andrew Simms, and Jo Michell, is available here.

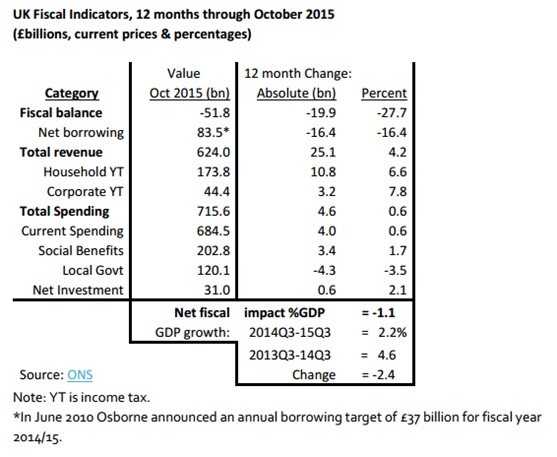

When he became chancellor in May 2010 George Osborne pledged to eliminate the fiscal deficit, to “balance the books”. In his first budget statement that summer he set a specific target, to borrow no more than £37 billion during fiscal year 2014/2015. That fiscal year ended on 31 March 2015, and borrowing for the fiscal year weighed in at a tidy £90 billion, which by simple subtraction yields an over-run of £53 billion.

The table below shows the major UK fiscal indicators for the latest available statistics, the 12 months ending 30 October 2015. Despite not meeting the target he set for himself, the chancellor has boasted of success because the overall fiscal balance (i.e. government revenues less spending) is now just over minus £50 billion compared to over £100 billion when he took over Britain’s public finances (borrowing and fiscal balance numbers in the table differ due to asset sales, almost all from bailed out banks).

This heart-felt self-congratulation inspires skepticism for three reasons.

First, the cost in human suffering of the fiscal “savings” has been enormous, felt most acutely through the devastation of local government services. Over the 12 months covered in the table, local government funding fell by over £4 billion or 3.5 percent of total spending by councils.

Though central government spending on social “benefits” (aka what we pay taxes for) increased slightly, adjustment for inflation and population increase renders the change close to zero.

Second, the reduction in the fiscal deficit and borrowing resulted from tax revenue increases not from cuts in spending. Total spending actually rose by £4.6 billion, outweighed by a revenue increase of £25 billion (almost all coming from household income taxes and VAT).

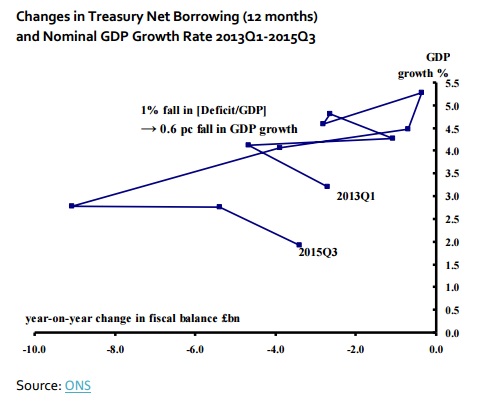

The implication of the second source of skepticism yields a third, that the budget cuts prevented a balancing of the books. A look at the chart below tells the tale. The fall in the deficit has been strongly linked with falls in the GDP growth rate (across the ten quarters a decline in the fiscal deficit of one percentage point was associated with a fall in GDP growth of 0.6 percentage points).

The causality is obvious. Tax revenues increase when GDP increases (and people’s income increases); cutting public spending reduces overall demand, depressing GDP growth. During the 12 months covered in the table the net overall effect of the chancellor’s fiscal policy was a negative 1.1% of GDP.

The depressing effect of fiscal policy shows in GDP growth itself, which declined in current prices by 2.4 percentage points during the 12 months through 2015Q3 compared to the previous 12 (2013Q3 – 2014Q3). The larger fall in GDP growth than the fiscal drag results from a slightly negative trade effect, slowdown in private investment, and the expenditure multiplier magnifying all three.

A review of fiscal policy for 2015 shows what we should expect. The UK economy remains demand-constrained, and the Chancellor’s policies made that straitjacket ever tighter. We should compliment the chancellor for not achieving his £37 billion borrowing target for fiscal year 2014/2015. To have done so would have made a bad performance wors

The UK is an interesting one. I don’t think Osborne’s fiscal policy is very bad at all and certainly not ‘failing’ considering how badly other countries are performing by implementing a leftist policy (Italy, France, Brazil), he’s managed to cut taxes quite significantly on income tax, corporation tax and many others, which has boosted consumer spending and real incomes. Whilst implementing tough welfare cuts that have boosted the employment rate to the highest rate ever, an incredible achievement when participation rates still haven’t recovered in most of the west. Also, by implementing a higher minimum wage he’s increasing demand and putting the cost on employers, instead of the taxpayer.

Compared to its neighbours, who barely mange any growth at all, at almost 3% a year, the UK is doing incredibly well.

Remember that the UK has their own currency, unlike their neighbors. Given that huge advantage, I grade Osborne a C- at best.

Ben your a government mole straight conservative propaganda. I don’t believe the government figures any more than I did when I lived in the States. Without the consumer and its debt this economy would be sunk!

I agree that the UK government has made sure that common economic targets reported in the press look acceptable (unemployment, gdp etc). However, these numbers hide a multitude of ‘sins’. The growth of low pay and insecure jobs (including self-employment), the growth of food banks, the reliance on the housing market to feed GDP, encouraging increases in household debt burden (OBR forecasts on GDP growth are depending on increased debt).and encouraging pensioners to spend their savings (pension lump sums). Meanwhile productivity (necessary for productive economic growth) is languishing at the lowest levels seen for decades, manufacturing is in recession, business investment is also languishing at low levels and we are in a deflationary environment which is deadly when combined with high levels of household debt. This is not the picture of a sustainable well-managed economy. And more importantly, there is palpable misery within the population as households struggle to keep their heads above water.

U.S. fiscal stimulus was running at about 2.5% of GDP in 2015.

Apparently the budget deal and tax extenders bill might have added a couple of tenths of a percent stimulus, though not a peep of commentary can be found with a casual internet search.

At this point, the $1.5 billion Powerball jackpot is probably our brightest hope. /sarc

1 that Powerball money is not new money.

2 it takes money from those ready to spend on something else and puts it in one place, where the most profligate person in the world can’t hope to completely throw away immediately.

Not only are you correct, but also since .gov takes a third of the jackpot as tax, lotteries represent negative fiscal stimulus (i.e., state-sponsored austerity).

That said, if you win, I could use a beer …

Oh, yeah, I forgot our ever-vigilant inflation fighter – the tax person.

I find it absurd in the extreme to call austerity a policy, as if there was any research to back up the decision. Conservatives have pitched a fit about cash going to poor people, that they think should be diverted to crooked contracts and shady business deals. Soon they will be fighting among themselves for who gets the government deals to keep their loot.

Hey, you look bad when you single out “conservatives” (I don’t even know what that word is supposed to mean anymore) for your ire. All politicians everywhere are doing their best to shower their very good friends with money. And funny how you mention crooked contracts and shady business deals when HRC just now happens to be running for president as a “liberal”.

“Though central government spending on social “benefits” (aka what we pay taxes for)”

I’m going out on a limb here, since I admit I’m not familiar with the unique specifics of how the UK government is funded, but per MMT, this is wrong, isn’t it? In point of fact the citizens of Britain don’t fund the central government through taxes, right?

Also this article seems to be rehashing the same old ‘austerity is bad partly because it doesn’t even do what it sets out to do: reduce the deficit and pay back the debt’ fallacies. Deficits are a good thing and sovereign debt doesn’t need to be ‘payed back’. I really wish there were more articles that talked about what this public debt even is. It isn’t money owed to other entities! Western countries aren’t borrowing money from elsewhere to pay their bills!

That’s true but I think it’s a little more nuanced to keep taxes in the equation.

From Bill Mitchell, http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=32755

“”It follows that the imposition of the taxation liability creates a demand for the government currency in the non-government sector which allows the government to pursue its economic and social policy program.

This insight allows us to see another dimension of taxation which is lost in orthodox analysis.

Further, while real resources are transferred, the taxation provides no additional financial capacity to the government of issue.

Conceptualising the relationship between the government and non-government sectors in this way makes it clear that it is government spending that provides the paid work which eliminates the unemployment created by the taxes.

That governments, as long as they can enforce the rule of law, have many options available to ensure they have sufficient taxing capacity to create the necessary real resource space to accommodate a public spending program.””

—–

The government spends money to help create wages. People have to sell goods to obtain money to pay taxes. These goods as well as the associated jobs can be directed to social programs.