Yves here. Economists have been hand-wringing recently over falling labor productivity in the US. Wolf Richter gives an update and some implications.

By Wolf Richter, a San Francisco based executive, entrepreneur, start up specialist, and author, with extensive international work experience. Originally published at Wolf Street.

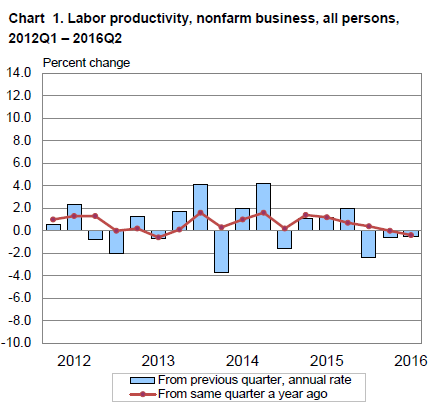

This cannot be good for jobs: In the second quarter, nonfarm business sector labor productivity – defined as output per hour worked – fell by an annual rate of 0.5% from the first quarter, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. The third quarterly decline in a row.

The last time it dropped for three quarters in a row was from Q3 1973 through Q3 1974 (5 quarters). Alas, in November 1973, the economy entered a recession. Several quarters in a row of declining productivity is not kind to the economy.

The productivity decline in the second quarter this year was the result of output edging up at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 1.2% while hours worked to obtain this output rose 1.8%. Year-over-year, productivity fell 0.4%.

Here is what this looks like on a quarterly (blue columns) and year-over-year (red line) basis (chart via BLS):

At the same time, unit labor cost rose 2.0% in the second quarter, the result of a 1.5% increase in hourly compensation and the 0.5% decline in productivity. Year-over-year, unit labor costs increased by 2.1%.

Ideally, compensation rises to give workers more spending money, and productivity rises as much or more, so that workers and employers both come out ahead. But that’s not happening.

So what’s wrong? Why is productivity growth so miserably low? And it’s not because Americans somehow forgot to work. Krishen Rangasamy, Senior Economist at Economics and Strategy, National Bank of Canada, put it this way:

Borrowing by corporations for the purposes of stock buybacks instead of investment in machinery and equipment does little to enhance an economy’s capacity for growth. We’re getting more evidence of that in the US where the average age of fixed assets is the highest in half a century and productivity growth is the weakest on records.

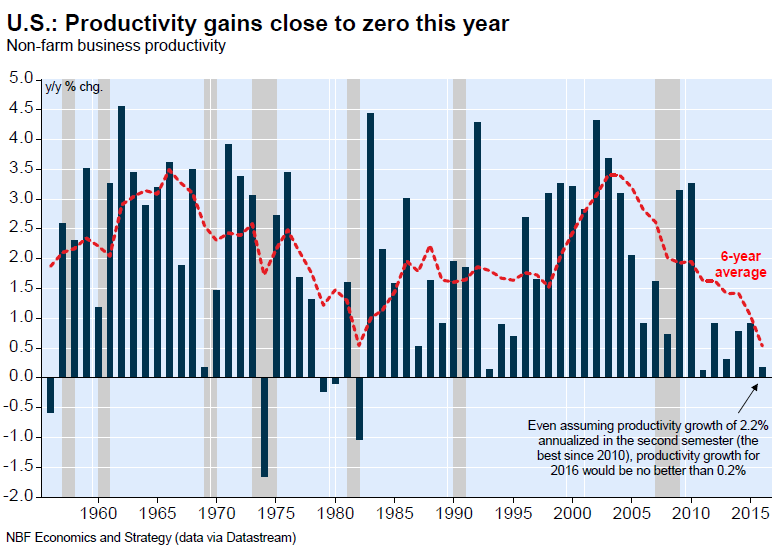

Given the productivity declines in the first half of the year, and even assuming productivity grows in the second semester at the fastest pace in six years, productivity growth in 2016 is set to be close to zero. As today’s Hot Chart shows, that would mean a six-year average of roughly 0.5% for productivity growth, the lowest ever recorded. That cannot be bullish for the US labor market.

In Rangasamy’s annual chart below, the red line that has been in decline since 2003 represents the 6-year average productivity growth. Even if his best-case forecast of 2.2% productivity growth in the second half plays out, productivity growth for the whole year will drop to near zero, and the 6-year average would hit 0.5%, “the lowest ever recorded”:

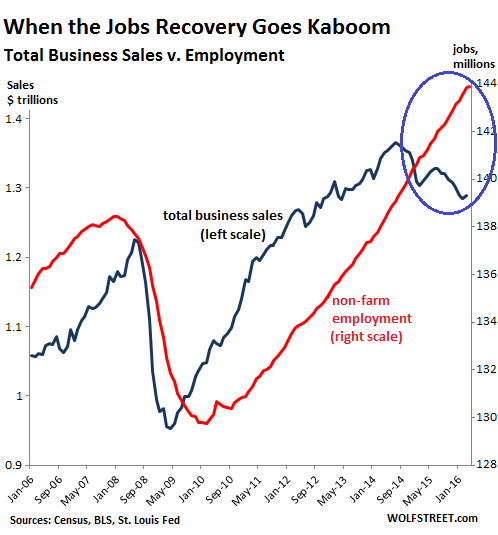

It will eventually impact the labor market. Here’s why: despite the hiring that companies have been doing, sales – the ultimate measure of “output” – have been heading south since mid-2014.

Total business sales, according to Census Bureau data, which include sales within the US by all companies, not just the largest in the S&P 500, peaked in July 2014 at $1.35 trillion. By May this year, the most recent data available, they’d dropped 4.4% to $1.29 trillion.

Despite sales cascading lower for a year-and-a-half, nonfarm employment from June 2014 through July 2016 has risen by 5.6 million jobs! And that’s what the productivity decline is also showing: the additional labor hours have been accompanied by a decline in sales!

The chart shows how jobs and total business sales are normally on the same wave length: When sales get hit, businesses cut their payrolls; when sales pick up, businesses hire. But since June 2014, a peculiar phenomenon has set in, with employment (blue line, left scale) rising and sales (red line, right scale) falling:

Note that the Census Bureau once again adjusted its numbers for total business sales – downward as always. Since I’m a stickler for numbers, and for pointing out rose-tinted data-set bias, I have added the old numbers (brown line) to the revised numbers (red line).

Some economists contend that the measurement of productivity itself is off because it just can’t be this bad! They contend that the government is doing a lousy job measuring productivity in the modern gig-and-social-media economy. That may be true. But the relationship between declining sales and rising employment points at a core problem: productivity is down – and is down sharply – or else, rising employment would lead to rising sales.

Clearly, something is amiss. Sales and productivity cannot decline forever while companies continue to hire. Eventually companies are going to react in large numbers. They’re either going to perform miracles and get their sales to jump through hoops, or if that fails, they’re going to bring their workforce in line with their lower sales. And that would be when the jobs recovery, as miserable as it has been, gets crushed.

In fact, on an individual basis, on a per-capita basis, the employment situation has barely improved since the Great Recession. Read… Why this Job Market is Still Terrible: The Politically Incorrect Numbers Everyone is Hushing up

So … part time jobs are skewing the numbers.

You don’t have job security when you only have a part time job and you spend accordingly

You lose productivity when you have to account for start up and shut down time in fewer hours.

And … we’re moving toward more part time jobs as employers cut hours to avoid mandated full time employee expenses.

Policy manners.

Every time I see the word ‘Productivity’ I hear ‘more work, less pay’ chanting in the background. What used to take – and still takes – 3 weeks, my employers expect to accomplish in 1 week.

Raw materials are no longer in stock in sufficient quantity. Everything is increasingly requiring lead time. Suppliers are reporting that they are getting shipments in by rail rather than truck which is fine, but it adds extra time to ordering.

In talking with suppliers, there seems to be a bit of chicken egg going on. Since 2008, orders have trended down, so new stock is not ordered, which adds lead time, which minimizes choices, giving preference to orders for what’s available, it’s like a feedback loop and seems to be picking up speed.

Ymmv.

In other words —crapification.

Could it be that we’re looking at this the wrong way? Is it possible that continual increases in output per worker-hour are unsustainable, given that the inevitable end point of such increases is one worker doing all the work?

I don’t have an answer, just questions, but it does seem as if there’s a logical fallacy bundled up in the assumption that productivity must always and everywhere increase.

Is there a point of stasis that would also satisfy?

You’re right; there is a logical fallacy bundled up in the entire discussion of productivity: it’s like saying “greater density implies greater volume” or “greater speed implies greater time”. Just the opposite tends to be true. Greater speed at constant distance implies less time. Greater speed for fixed time implies greater distance. When one gets both greater speed and greater time, distance becomes doubly greater.

In productivity, the time worked and the number of workers are in the denominator. One has no business assuming that increased productivity results in increased employment. Mitt Romney’s field of business often included increasing productivity by laying off workers.

It’s more like we are getting better at fixing the broken windows that increase GDP but makes us poorer over time.

The reality is an increasing percentage of our growth is based on consuming energy and resources on non-essentials… How can we actually expect perpetual increasing efficiency in wasteful activities? The planet will fail us. It already is billions of us.

I have to admit that I am the first to enjoy my creature comforts by I am also open to the idea that I was born in a special time that will probably not last.

Easy come, easy go.

Isn’t multi-factor productivity the more robust indicator to look at when analyzing the evolution of productivity?

Could the low-productivity be the result of too many workers willing to work long hours for low pay?

I don’t think it’s a matter of willingness. I think it’s a matter of having to work those hours — or else.

As for the productivity declines, could this be a way of going on strike without going on strike? Could American workers be raising a collective middle finger to bosses who keep wanting them to work harder, harder, and harder? But the rewards just don’t seem to come?

The productivity “calculation” is bogus – and that is the nicest characterization!

The job additions use part time jobs, as little as ten hours, as equal to a 40 hour full time job in their job addition numbers each month.

As the jobs crossed the 55% mark in terms of total jobs being part time and the avoidance of the 30 hour threshold for Obamacare to kick in for employer responsibility if they keep the workers on the payroll, the whole metric comparison to the past becomes irrelevant.

Barack Peddling Fiction Obama, on so many levels of economic policy, has been a disaster.

The BS at the Obama B.L.S. is now part of the propaganda for political objectives which have no relevance to analysis of what is going on in the real world.

The same Obama game is played with the UE Rate, where part time workers when laid off cant get Unemployment Compensation which is the gateway information source to the calculation of the Rate. There is also extended waiting periods for filing which reduce the aggregate people on unemployment. If you go out of the country to do an interview for example, you cannot file from a server which they have marked outside the US, so you lose a weeks registration. Many rules like these contribute to gaming the system and keeping the Rate down.

In the middle of the Gobi desert water is scarce, and people use it very efficiently. At the base of Niagara Falls, water is abundant, and people take little care if it spills or is wasted.

Water is valuable in the Gobi desert because it is scarce, and it is used efficiently there because it is valuable. Investing in expensive water-conservation equipment at the base of Niagara falls is 1. Stupid and 2. will not increase the value of labor.

If productivity is falling, it is because real labor costs are falling (‘per unit’ costs ignore the impact of illegal immigrants and the effects of employing higher quality labor at wages that used to be reserved for lower-quality labor).

Productivity does not cause high wages. High wages cause productivity.

And the notion that automation is the problem is clearly nonsense – if that were true, productivity numbers should be skyrocketing as the last person standing in an automated factory produces a million dollars a day in product…

In my opinion, the way productivity is measured has major flaws which are only now becoming visible. If you want to increase the productivity of a guy breaking rocks with a sledge hammer, the way to do it is give him a big diesel powered, hydraulic rock crusher and, boom, his productivity increases by a factor of 500. But this strategy only works in a sparsely populated world with abundant, cheap resources. When you enter a world where limits become visible everywhere (population, resource availability, waste dumping capacity) that strategy no longer works. We are in such an environment and there is going to be a long slow decline in labor productivity, unless we jigger the metrics to get the numbers we want to see.

Yup, the solution is called multi-factor productivity. Difficult to compute, but actually meaningful.

Agreed.

How much energy and resources did it take to break that rock? From the plant that needed to be built to produce the machinery, the roads to deliver it. The oil to power it. The schools that were built to educate the worker…

A lot of mispricing and externalities which are probably catching up with us.

Maybe the link Wolf is assuming between rising wages/employment and rising sales has been weakened – or even broken – as the Great Recession grinds on for the 99% and they spend whatever extra money they get on paying down debt or, for the lucky few, actually manage to save some of it. From an MMT perspective, of course, these 2 ways of using extra cash are equivalent so to get actual spending to increase a much more substantial increase in total hourly earnings is needed (*) .. esp. when businesses would rather use their cash pile on CEO compensation boosting measures than on investment for the longer term, so that path to increased sales is, as Wolf mentions, currently blocked off.

(*) Which is, of course, what a fiscal stimulus is all about … as some economist pointed out in the 1930s, can’t recall the name just now but it’ll come to me soon. Kind of like the activation energy needed to start some chemical reactions

Productivity measurements were standardized back when the US had a manufacturing economy, before so many of the good manufacturing jobs were off-shored.

What are we producing now? Service jobs are hard to mechanized or industrialize. A gig-economy isn’t a manufacturing economy – to say the obvious. Why are some economists confused by this? How does an Uber driver increase his “productivity?”

Before productivity decline came productivity growth decline;and some linked that to unprecedented decline in test scores between 1967 and 1980.

See:

“The test score decline between 1967 and 1980 was large (about 1.25 grade-level equivalents) and

historically unprecedented. New estimates of trend in academic achievement, of the effect of academic

achievement on productivity and of trend in the quality of the work force are developed. They imply that if test scores had continued to grow after 1967 at the rate that prevailed in the previous quarter century, labor

quality would now be 2.9 percent higher and 1987 GNP $86 billion higher.”

http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1034&context=articles

Is the Test Score Decline Responsible for Productivity Growth Decline?

They are automating more and using IT more and this is happening.

Will continue to go down as America ages;and in pipeline are mostly poor students in public schools. Neither will be positive for sales.

I note on the Total Business Sales to Employment chart that jobs led sales pre-2008, but that is reversed since 2008. I also note in the chart depicting yoy and longer-term productivity a similarity in the shape of the trace for the latter to others I’ve seen depicting demographic and technological trends. Note the twin peaks and relative trough. It appears to be generational, with the rise in productivity driven by the heart of both technology sets and working lives – and falls as that generation’s entire workforce does less with the ensemble of skills and advantages acquired but also stays as along as possible until retirement, especially post-2008 (note my first note). Within the large cycle, recessions repeatedly squeeze huge temporary gains by firing labour and working the rest harder – especially the best. But the ‘real’ productivity comes as the next generation comes into its own having thoroughly incorporated into their efforts the sum of all the techniques passed on to them and thus the capacity to see possibilities where their predecessors could not. The troughs would appear to correspond to inter-generational incubation of technology and young talent with false leads, dead ends and opposition from the status quo. Critically, we have to remember that the vast majority of ‘work’ now performed is entirely superfluous to our needs, but that fact in no way justifies paying stupendous sums to ‘talent’ and debt servitude for the rest.

The critical issue is whether or not this apparent pattern holds, and that the deep slide is into the next trough and starting back out during the mid-2020’s or whether this inter-generational transition is doomed by instability to be a trip to something altogether different.