By Ian Goldin, Professor of Globalisation and Development, University of Oxford and Chris Kutarna, Fellow, Oxford Martin School, University of Oxford. Originally published at VoxEU

Some economists see currently faltering GDP growth as part of a longer-term trend for advanced economies, reflecting their belief that the bulk of technological innovation is now behind humankind. This column argues that neither history nor the present-day pace of scientific discovery supports the notion of diminishing returns to technological innovation. The challenge for growth economists is that analytic models are poorly suited to capturing and setting society’s expectations for these impending disruptions.

Advanced economies in the 21st century are caught between two giant, competing truths: economic growth is slowing down, and science is flourishing.

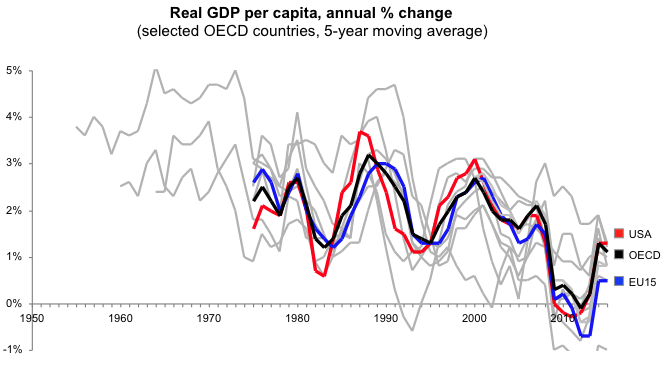

Per-capita GDP growth is trending downward across the OECD (Figure 1). Among other explanations (rising inequality and debt levels, for example), economic theory variously attributes this trend to diminishing returns – from the one-time transition of women into the labour force (Bloom et al. 2003), from human capital improvements via higher education (Goldin and Katz 1998), or from the exploitation of natural capital (Costanza et al. 1997).

Figure 1. Real GDP per capital, annual percentage change

Recently, Robert Gordon (2012) highlighted another site of diminishing returns, namely, technological innovation. Via a longitudinal study of US labour productivity from the 19th century to the 21st, he showed that the advent of computing and digital communications, for all their seemingly transformational impact upon society, haven’t generated much economic growth when set in historical terms. The innovations to which the generations at the beginning of his study bore witness (public sanitation, electricity and combustion engines) drove rapid US labour productivity improvements for 80 years. Computers and information technologies, however, drove equivalent rates of improvement for only ten years. Average US wages rose 350% in the 40 years between 1932 and 1972, but only 22% over the next 40 years. The pattern holds similar across the developed world. In other words, for all their hype, the computer and the internet have done less to lift economic growth than the flush toilet.

The implication is that the truly transformational innovations may already be behind us. Before, we couldn’t harness electricity – now we can. We couldn’t maintain sanitary living conditions – now we can. We couldn’t get from any A to any B – now we can. We couldn’t talk to anyone anywhere anytime – now we can. Whatever’s left – driverless cars, or even quantum teleportation – might prove incremental in comparison. This line of argument imagines technological innovation to be like pulling balls from an urn, each ball representing a new idea. In the beginning, the urn was full and the spheres were large, but each time we’ve gone back to the urn, we’ve had to reach deeper than the last, and the spheres have dwindled into marbles.

In a new book, we argue that this metaphor, while intuitive and compelling, is backwards (Goldin and Kutarna 2016). Innovation is more like mixing compounds in an alchemist’s lab. Each compound is an existing idea or technology, and in the beginning we had just a few – maybe some salt, sugar, and common liquids. But then we tried mixing them together, and some of them reacted with one another to form new compounds. Before long, our once-sparse workbench was crowded with acids, alcohols, and powders. Every time we enter the lab to cook up something new, we are confronted by a wider range of compounds than the last. We need never fear running out of powerful new combinations to try. The fear, rather, is that new compounds and their possible combinations are multiplying so fast that we may fail to find the most useful reactions that lie buried among them.

This metaphor is far closer to the present experience in research laboratories. Across the sciences, the pace of discovery is generally rising, not falling. For reliable evidence, consider the pharmaceuticals industry (a good litmus test because it invests more into R&D than any other industry, except aerospace). The year 2013 set a new record for total drugs launched world-wide (48) – a record that was promptly beaten in 2014 (61). With another 46 drugs launched in 2015, the last three years have been the industry’s three most productive in its history. Recent major discoveries include new weapons against heart failure, which in an aging world is now the leading cause of death; immunotherapies, which help to defeat cancers by boosting the body’s own immune response; and a viable pathway to effective Alzheimer’s medications within a decade. In part thanks to the accelerating pace of pharmaceutical achievements like these, average life expectancy across advanced economies is now rising an unprecedented four to five hours per day.

Of course, for a hardened growth sceptic, such evidence may do little to overturn the broader thesis that returns to technological innovation are diminishing (indeed, it may strengthen that thesis, since one of the consequences of a ballooning population of healthy retirees, ceteris paribus, would be deteriorating output per capita). From an economics standpoint, the transforming pharmaceutical breakthrough was the invention of a pharmaceuticals industry – drug discoveries made and distributed within that paradigm, no matter how important or frequent, are all incremental gains by definition.

However, what if the whole paradigm were to shift? ‘Paradigm shifts’, in the sense that Kuhn (1962) described in his Structure of Scientific Revolutions, re-introduce the possibility of transformational change, by shifting scientific endeavour out of theoretical frameworks whose limits are being approached and into new ones whose limits have not yet been explored. The classic example is the Copernican Revolution, which by challenging medieval theories of motion ultimately gave birth to the Newtonian physics upon which most modern machines are now based.

Such paradigm shifts are underway right now, and will undoubtedly disrupt and reconfigure advanced societies over the next 30 to 50 years. Medical science is not merely discovering new drugs. The advent of synthetic biology – the capacity to design and modify organisms at the genetic level – promises to eventually shift the societal role of medicine from the treatment paradigm that has prevailed for 5,000 years to one of transforming organisms to give them overwhelming natural advantages against disease and aging. Within this new paradigm lifespan, intelligence, and other basic human characteristics may quickly evolve beyond ranges that we consider normal today. As they develop, such medical technologies will also raise the most difficult ethical questions that science has ever presented society – what about us makes us human? Should (and can) humans and trans-humans coexist?

Another source of societal disruption will be artificial intelligence, which is rapidly shifting the role of computers from being tools for calculation to tools for cognition. This shift has near-term implications for the structure of the labour market (according to the Oxford Martin School, almost half of all current jobs in the US have a high likelihood of being automated away by 2050; see Frey and Osborne 2013), but the more profound disruption will be to prevailing conceptions of free will. Many of the choices we take for granted in our daily lives today – which routes we drive, what products we purchase, what media we consume – will rapidly become subject to AI scrutiny that will unveil a range of individual and social consequences to which we are presently ignorant. As this new cognitive layer over collective private action increases in strength and reliability, how will that domain of private action be affected? Will we be permitted to continue socially harmful activities in defiance of such evidence? Will elaborate incentives arise that cause our individual behaviours to conform to optimisation algorithms? And who will hold the authority to set and adjust such algorithms?

Similarly, profound transformations to society as we know it now are suggested by present pathways of inquiry into quantum mechanics, nanotechnology, and neuroscience. The proximate cause for these paradigm shifts is digital computers, which can peer more deeply and accurately into data than any prior analogue instrument. Because of their (exponentially increasing) power to crunch giant datasets and discern ‘signals’ from ‘noise’, computers have already done, and will continue to do, more to advance astronomy than the invention of the telescope, more to advance biology than the microscope, and more to advance physics than the particle accelerator (Robertson 1998, 2003). The golden age of labour productivity growth to which Gordon’s longitudinal research points – that single lifetime during which planes, automobiles and electricity arrived together to define modernity – was founded upon a relatively simple set of discoveries: abundant oil under the ground, internal combustion engines, germ theory, etc. Now we possess the tools to begin exploring the genuinely hard questions that reality presents. All science today stands near the base of a steep learning curve.

The broader cause for these emerging paradigm shifts is the inflation in human brainpower that has taken place over the past 25 years. Thanks to giant medical successes against childhood disease and aging over the past quarter-century, the present global cohort of adults is humanity’s largest and healthiest ever. It is also the best-educated. In just a generation, illiteracy has fallen from nearly half to just one-sixth of humanity. In 30 years, we’ve added three billion literate brains to our ranks. Meanwhile, the rapid expansion of higher learning in Asia means that the number of people alive right now with a university degree is greater than the total number of degrees awarded in history prior to 1980. Most importantly, the present generation is history’s best-connected, thanks principally to a quartet of big events – the end of the Cold War, waves of democratisation across Latin America, much of Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, China’s emergence from autarky, and the advent of digital communications.

Neither history, nor the present-day pace of scientific discovery supports the notion of diminishing returns to technological innovation. The challenge for growth economists is that analytic models are poorly suited to capture, and set society’s expectations for, these impending disruptions. Some consequences will be too pervasive and long-term to show up clearly in the immediate data. Some will change our behaviours, and by doing so invalidate prevailing economic assumptions. And some will transcend the economic sphere entirely to touch higher human values.

Growth economics is powerful. At its best, it is an empirical science that helps determine how to lift human wellbeing – one of civilisation’s most important tasks. But it is unable to capture the dynamism of our new age of discovery for a reason. Much that matters is still beyond its sight.

See original post for references

Shorter version: Humanity is Fokked.

Yup, the 0.1% will live on their vast, robot-tended estates while the rest of what Malthus would call the excess population is “right-sized” by drones.

Surprising where robots are heading (or already arrived in recent years)—such as milking cows. Farmers can be away night and day or out all night.

Why would a robot need milk?

I think this comment wins the day – funny and really, really to the point.

a Farmer, a Robot, and a Politician walk into a bar …..

A little while later the robot walks out, followed by the politician speaking robot-ese. The farmer’s never seen again.

Domo arigatou Mr. Roboto……

A friend who grew up on a dairy farm says her family was pretty much chained to it 24/7. Not a joke when you have to live it.

Thanks for posting this, an excellent insight into the minds and mindset that are driving our trajectory to dystopia. I could poke at one of the many enormous holes in the argument, but that would be missing the point, I think.

A person can live longer with a chronic illness only as long as they can afford the drugs to maintain it. And, as some of the research on opiods has shown, drugs can have the effect of keeping the illnesses chronic.

Diminishing returns, indeed.

http://www.theonion.com/article/bridge-to-21st-century-crap-forgotten-925

Our economy is being statutorily transformed by driving out that nasty business of making stuff to make room for “high level intellectual processing” jobs! – made competitive by staffing/threatening to staff with H-1B employees!

Yeaaaa!

What was the question again?

Can’t believe this nonsense is published. There are so many falsehoods here… should be classified as agnotology. Innovation is not like pulling balls from an urn, which has a finite volume and can therefore hold a finite number of balls. Innovation is like drawing from an infinitely deep well. Of course there are an infinite number of new innovations available. But at a certain point they are not worth retrieving.

And then there is the postmodern Kuhnian paradigm-shift nonsense. Scientific conceptual breakthroughs DO NOT invalidate existing theories. Just one example: Einstien’s General Theory of relativity did not overturn either Newton’s or Maxwell’s work (which were mutually incompatible). Einstien’s reformulation of the common sense notion of time actually resolved those conflicting theories and we can still use Newton and Maxwell to this day.

The last paragraph is a whopper. An empirically invisible miracle will save us. Deus ex machina…Sidney Harris’s “Then A Miracle Occurs” cartoon would be appropriate here.

One of the few things I read attributed to Ben Bernake, although not an original thought perse, but nonetheless seemingly accurate:

:”…innovation, almost by definition, involves ideas that no one has yet had, which means that forecasts of future technological change can be, and often are, wildly wrong. A safe prediction, I think, is that human innovation and creativity will continue; it is part of our very nature. Another prediction, just as safe, is that people will nevertheless continue to forecast the end of innovation.”

Should I be concerned that I agree with Ben Bernanke?

Rock,spear,arrow, bullet, poison gas, bio weapons, autonomous battle machines, nuclear device… Yah, love me some Fokking “innovation…” Don’t forget “the promise of CRISP.ER…”

Rock,spear,arrow, bullet, poison gas, bio weapons, autonomous battle machines, nuclear device… rock,spear, arrow… repeat

None of those frighten me as much as CRSP-R. Once that breaks free from a lab and it’s incinerators, the law of unintended consequences takes over and there’s no reset.

History has shown that we can innovate like crazy and still leave billions of individuals in poverty.

And kill billions on the way to “novelty…” Not to mention millions of other creature of so many species, and whole swathes of the necessities for simple habitability of the planet.

Heh, a miracle indeed. Kind of funny that the authors are Oxford-affiliated yet their stuff shows up here in the comic sense of “there are n things wrong with this picture — can you find them all?”

To add to your points, I’ll highlight their mixing up of “Science” as an idealized abstract conception of a process, with implicit inevitability of progress and the alternative “Science” as it so happens to be practiced in a particular culture at a particular time.

Some recent NC links have been great at showing the damage caused in the sciences by the current bad structures of funding, hiring, and publishing that reward carelessness and narcissism.

To your point, “But at a certain point they are not worth retrieving,” I’ll merely add that at certain points the complexity becomes too great for key foundational knowledge to transfer to newer generations. And the learning curve becomes so daunting that the diligent folks invariably get outpaced by the careerists, fakers and self-promoters. This leads to a cycle of generations always “discovering America.”

One wonders if the authors can account for the lack of new Beethovens and the quantity of revenue-producing crap in the music world, and whether they see how that dynamic applies to the practice of science today.

There’s a reason the story of the Tower of Babel is in the Holly Bibble…

The one scientific breakthrough that could redeem this post and make these authors intellectual heroes for generations of optimistic humanists — and this would be a Nobel Prize invention for sure — would be a “Handheld Don Juan Seduction Beam”.device.

If you were, for example, on your 5th beer in a dive bar and saw a hot female. but you were too drunk to really make a good impression — you can fumble around for your “Don Juan Seduction Beam” device in your pocket, point it at her and press the button

Then she tackles you. Getting her out the door should be easy after that. This is science at its best — waiting out there in that mind land only geniuses can see, but they need to work at it. They can’t just say “It’s impossible.” Of course if your the woman you may need a Don Juan Seduction Beam blocker to keep you out of trouble. These devices could make for an economic boom.

Ptolemy >>> Copernicus/Galileo? Your point re Einstein works, but that, uh, paradigm of paradigm circumscription doesn’t always hold.

“Innovation is more like mixing compounds in an alchemist’s lab. Each compound is an existing idea or technology, and in the beginning we had just a few – maybe some salt, sugar, and common liquids.”

Just wanted to mention that the abundance of and access to these compounds/components is determined by the natural environment and your society’s ability to exploit it. If your society can’t access them (perhaps its a strategic resource that someone claimed for themselves and they aren’t sharing much of it) or the supply is exhausted (perhaps it is a highly demanded commodity) then you are going to have a hard time being “innovative”.

Exactly. And if you use up all the rare earth metals necessary for advanced technology by pumping out the next generation of disposable phones and ipads every year, there won’t be much left a few hundred or thousand years hence for the supposed transhumans to use to outfit themselves with whatever gadgetry they might require.

Utter claptrap. Why can’t these guys ever talk about current inventions that are creating millions of jobs over the one’s being destroyed? Always something very vague that happens at some vague time in the future. It seems to say “Keep plugging away at that meaningless, minimum-wage job pal, because your payday is right around the corner! No need to vote your personal interests right now!”

Yes. Obviously productivity increases need to be ethically financed or the profits are not justly shared.

Economics is the laggard.

If innovation is the application of existing ideas, little innovation can be expected in economics when the prevailing ideas are so rancid.

Nevertheless, if technological innovation was to be blamed i wouldn’t expect diminishing returns per capita. It would cause decelerating increases.

The elephant in the room being ignored is the fact that infinite growth is impossible. Natural and immutable limitations are bound to assert themselves. It’s always amusing to watch economist scratching their heads trying to figure why the impossible isn’t happening.

IMHO this is quite a medieval assertion. Long ago creationism was also natural and inmutable, the earth was flat and in the middle of the universe.

‘fact that infinite growth is impossible’

Agree b/c these following factors:

-Continuing Depletion of RESOURCES

-Degradation of the Environment in various degrees, all over the World

-unchecked population growth, accelerating both of the above!

Wonder, US GDP growth in 20th used to be above 3-4 and even 5% per annum. Now in 21st century, it is consistently just around or BELOW 2%. Soon it will be 1% or less in a decade or two if not earlier!

+1

When people talk about technological revolution, they often fail to consider the additional complexity that comes with these technological changes. It is this complexity, and our inability to fully comprehend our place in that complexity, or its feedback on our lives, that will likely provide the ultimate limits to growth or advancement. Complexity will result in diminishing returns – it will limit growth. The complex solutions to old problems typically generate new and more complex problems that are more difficult to solve. For example, the technological innovation of fracking to obtain tight oil/gas has resulted in ground water pollution and has exacerbated climate change – problems that are orders of magnitude more difficult to solve. As the Fed attempts more and more elaborate, innovative schemes to prop up the house of cards, the house of debt, the shakier the entire economic system becomes. Our new innovation-driven growth is not based on simple principles of useful product development, but rather on marketing to create desire for unnecessary consumption and on riskier and riskier financial bets that create bubble economies ripe for collapse. In addition, the glue that holds the system together is based on faith and myths that are more difficult to sell as the financial cracks become fissures — soon to become crevasses. The economy has lost its way – forgotten why it was created – morphed into a profit driven machine rather than a needs driven social exchange.

Complexity hinders our ability to see the big picture since complexity forces us to focus on narrow problems and solutions which we can comprehend with our finite consciousness. Complexity blinds us – we can’t see the forest for the trees. We don’t even understand how our unconscious desires control and overrule our conscious “free won’t.” As we attempt more and more complex solutions to problems driven by desires, not by need, we create a whole new set of problems – blowback from our inability to see the bigger picture. The demand to innovate and show movement, defined as a growth of knowledge, is all that seems to matter in our capitalist culture – even when no one pays attention to that new knowledge – much like all the other garbage we discard. I think we are rapidly approaching the saturation point in our ability to use this new complex information in a beneficial way.

In my own narrow sub-field of physics, I used to be able to at least skim the journals and find those articles of interest and worth reading – to contemplate and discuss with others. But the demand for growth – growth of publications (publish or perish) and growth of people in my field (grad student production) has transformed the journals into masses of information with incremental results that lack placement in the broader understanding. Most of this new knowledge is useless. Fewer and fewer scientists see the bigger picture. Scientists are so driven to generate new results, to produce, that the journals are too thick to parse unless you do nothing else. And the articles that scientists recommend to others are often their own publications in the hope that someone else might read them. The internet tools help – I can now download an article much faster than going to the library. On the other hand I can’t read and digest that article any faster, and the increased number of articles published has reached the point where it is difficult to even find that useful article. The volume of information is growing too fast, and the older insights in the field are becoming lost to the newer generation of scientists who must attempt to rapidly innovate (or mimic what was already done) just to show progress. No time to develop wisdom.

Vader had it right: “Don’t be too proud of this technological terror you’ve constructed.”

I find here confussion between technological innovation and political will

For instance, imagine that the same amount of money and effort that has been used to develop fracking was used to develop geothermal energy the difference would be enormous but it is a question of political will rather than diminishing technological returns.

Geothermal is a nice dream of a panacea, but of course even a little dip into the literature shows that once again, hubris and greed and self-serving applied in Fokking with Gaia (shorthand for “the natural, unfortunately exploitable, refractory in the end, world”) is a big fail.

Already, it’s to the point that promoters of geothermal “investment” have to publish sh!t like this, “The Manageable Risks of Conventional Geothermal Power Systems,” http://geo-energy.org/reports/Geothermal%20Risks_Publication_2_4_2014.pdf

“Back off, man! I’m a scientist!”

well said! Couldn’t agree any more!

As retired MD (Diag Radiologist) I find the same scenario in general in Medicine in particular Diag Radiology!

Garbage In & garbage OUT, has taken over and obscures the ‘forest for the trees’!

You can dress up what is happening in all sorts of ways. When democracy has been stolen, when the political class has been bought and paid for by a small controlling elite, you have a decline into third world economics. The incentives to start businesses in the US have gone because of the worship of the large corporations who are able to pay for the necessary lobbying so that laws are skewed in their favour.

I guess when you sit in the safety of an academic institution, facing up to nothing more challenging than dreaming up ways to either provide intellectual cover for the plunder, or find ways to increase your take of the available government grants, then what you get is the nonsense above.

There is a very obvious paradigm shift going on which the article goes nowhere near. To do of course means that you would cease to be one of the ‘insiders’ or useful idiots.

Obviously, you have never been employed in an academic institution: Unless one is a tenured professor there is no such thing as “safety” in academics.

Most junior-level academics are on two-year contracts. The pay is not that great, there are usually no relocation programs since junior-level academics having a family is considered a dire waste of resources and if one wants to procure something one has to go to meetings with 20++ people who all also want theirs if someone else is getting some. All of these meetings are about managing a flock of spoiled children were a few are being given sweets. Most lower level academics (in the career sense) eventually “fail out” to private business and settle down once they realize that they will never make tenure, not even at a lower ranking university. This usually happens at the age of 30 or so.

Very few get full tenure. For those few finally becoming a tenured professor there is *still* the everlasting scrabbling for external funding, perpetual fights with other colleges over internal funding (now at a much higher level and against people truly skilled in the art, said skills acquired through years of dedicated effort in “undoing the competition”), and of course for space, resources and the good students.

A few tenured professors can do like Tolkien did: “Fuck this bullshit business, I’ll just be writing books which totally tangentially involves my specialty and teach, so they can’t sack me”.

Others will whore themselves out to whoever pays for specific results and maybe end up in a think-tank at 10x or even 50x the academic salary.

Most will just find a way to muddle through and enjoy what they are getting.

Firstly, yes I have.

Secondly I think your summary of who makes it to tenure is pretty accurate and sums up what it takes to get there and to stay there.

I was commenting on the mind-set of the people who wrote the article and their indulgence in a framing which misses so much that it beggars belief.

“We couldn’t maintain sanitary living conditions – now we can.”

==================================================

Uh, maybe not nearly as well as we used to. Everybody has heard of Flint MI

How many have heard of the water problems in Fresno, CA?

From the Fresno Bee:

Hundreds of homes in northeast Fresno have discolored water – and, in some cases, excessive levels of toxic lead – coming from their faucets.

And while homeowners clamor for answers about why and what to do about it, those answers are in painfully short supply.

There are a couple of common denominators to the cases: Homes that are plumbed with galvanized iron pipe and which also receive drinking water from the city’s northeast surface water treatment plant.

Read more here: http://www.fresnobee.com/news/local/article87594712.html#storylink=cpy

“Couldn’t” and “don’t” are two different things. We now have the understanding necessary to develop and maintain sanitary water for all. If we don’t do it, that is a social-political choice, not an inevitability. That was not the case when cholera transmission mechanisms weren’t understood, in the early 1800s.

This article is Panglossian in tone, but it isn’t as far off-base as its detractors. Living conditions have been improving dramatically outside the West for decades (with the notable exception of the Greater Middle East). What I see here in comments is a bunch of aging white English-speakers drenched in nostalgia, whose personal prospects are diminished, complaining about the fact that they and their society aren’t at the top of the heap anymore.

There are millions of 20-something men and women riding bullet trains in China who don’t give a shit about your sorrows and they are markedly better off than their parents. Despite immense, endemic corrupt the same may be said of millions in Indonesia, India, and Indochina.

In the greater scheme of things, the lamentations of 50-and 60-something fans of Kunstler don’t register.

>here are millions of 20-something men and women riding bullet trains in China who don’t give a shit about your sorrows and they are markedly better off than their parents.

Sure. Because riding a bullet train somehow means I’ve made it and “millions” in a country of over a billion doing that means… something?

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/15/world/asia/china-labor-strike-protest.html?_r=0

Are you any relation to Mr. Thomas Friedman, by chance?

It is entirely possible that industrial civilization is not sustainable.

It is probable that in its absence, most of us who are still alive will be impoverished and disease-ridden, just as we were in the non-industrial past and as people are in non-industrialized areas today.

What great choices the world gives us.

Want to see what comes next, maybe? For those who are healthy enough, with working major joints and strength and endurance and a healthy immune system, and intelligence and location amidst usable materials and the insight and knowledge to make stone tools and a kiln and all that (generating CO2, of course)? Here’s one how-to video (will his iPad and wifi work, post collapse?) — Build Your Own Tile Roofed Hut (with central heat!), http://m.youtube.com/watch?v=P73REgj-3UE. It’s part of a series…

That hut was pretty neat! But I hope we can manage more and better than that. What was most striking to me: 17,743,698 views. I’m not sure what that says but that seems like a lot of views.

I lost this article when the first example of optimism was the R&D in the pharmaceutical industry from massive corporate research, based on the sheer number of new whatzits.

Notice how that was carefully worded – you said “from massive corporate research” but I’m not really sure it said that — it was phrased so that I believe Federal R&D could be included b/c they -the feds- don’t actually make the pills.

Good point about the new “whatzits” – do they really freaking work? And what is more likely, with the corporate takeover of government it is just as likely that they’ve made the FDA a lapdog that will let them release pretty much anything than it is that they have increased their pace of discovery.

Wow, deep twaddle, a large froth of hype.This is like someone trying to sell a nuclear reactor (well… that’s what the sign somebody painted says anyway) and suggesting that one should twiddle all the dials to “give it a spin! It’s got infinite power!” What could go wrong?

Unless we have concerns about sustainability. For example, just collecting too many isotopic substances in too close proximity can have nasty consequences. More ≠ better, it’s just more, and more creates overhead, ignored at peril.

That’s not the fear, that’s the unfortunate byproduct of poor work habits. The fear is that we may discover reactions with dangerous/harmful consequences and side effects, and not immediately realize their dangers or the harms.

What, me worry? A.E.Neuman lives!

OMG, calculation wasn’t cognition for you? You need the computer to tell you the numbers you asked for are what you need? Then what are you asking for? The social disruption comes from people not understanding what they are actually doing, while telling themselves that the consequences will reflect their own fantasies.

I think that’s a naive read of history, and of the present day.

” Average US wages rose 350% in the 40 years between 1932 and 1972, but only 22% over the next 40 years. The pattern holds similar across the developed world. In other words, for all their hype, the computer and the internet have done less to lift economic growth than the flush toilet.”

ahem… the computer and the internet sped outsourcing to countries like China. Ask China or India how their economic growth has been since 1972. The author is mixing up several things at once.

Great comments, and please allow me to piggyback off them:

When so many of our jobs, technology and investment is offshored to China (and elsewhere), the future for innovation is certainly not bright, and this should be obvious to everyone, including the author.

When so many have contributed so much, only to see their jobs and livelihoods offshored again and again and again, that great jump the others have will then zero out OUR innovation!

Dismal or dazzling? How about: irrelevant.

Does nobody wonder WHY we need ever increasing levels of technological innovation and economic growth just to maintain the status quo? Isn’t there a logical disconnect here?

Bottom line: there is no level of technology that, with a large and fast enough growing population, it cannot be wiped out and the average person crushed into poverty. And even 500 year old technologies, with a modest population level, can provide a decent life for most with many luxuries.

I mean look at India: all the fruits of 500 years of technological progress and the physical standard of living is in many ways inferior to late medieval England. There are like half a billion chronically malnourished people in modern, technologically advanced India: in late Medieval England most people had plenty to eat and lots of luxuries like meat and beer etc.

Exponential population growth puts societies on a treadmill that goes faster and faster and steeper and steeper, until eventually it takes superhuman efforts just to stay in the same place.

Suggestion: stop trying to run faster. Get off the treadmill.

Seems to me the author needs to read up more on biology, geology, and thermodynamics. Considering we managed well enough for about 190,000 years with a minimal amount of culture and technology I think the jury is still out on the success of our 200 year experiment with industrialization, fossil fuel use, and “innovation”. The results thus far are not promising. As is always the case with human beings, the author poorly grasps the scale of time for the human experience. How can we know an innovation or technology is beneficial (broadly speaking) if we do not track its impact on the world over hundreds or possibly thousands of years? Fossil fuel consumption has been a complete catastrophe and it took nearly 200 years for us to understand its impacts. As a coworker of mine said, “technology is no replacement for a rational society”.

Typical economists and even worse, economists that are technophiliacs. A future utopia awaits!

Furthermore these types of idiots fail to realize that every environmental problem on the planet is a result of technology but not to worry more technology will fix it.

Testing.

Sorry — been having trouble getting comments to register.

Science and Innovation have no magical ties automatically generating economic growth or growth in human well being. I remember the quip I heard while contracting at a formerly AT&T facility: “Bell Labs could invent Eternal Life — but AT&T wouldn’t be able to bring it to market.” The innovations at Xerox PARC never found life at Xerox. English science was famed for its discoveries — while English Industry flailed and stagnated. Science and Innovation beget economic boons no more readily than outsourcing or automation magically beget better higher paying jobs to replace the jobs gone.

And why treat GDP and economic growth as the primary measures of growth and progress? Should our only progress be equated with mere material progress? Even if there were no worry about running out of resources, most people — excluding certain sociopaths and psychopaths — can only want and consume so much stuff. But can we know too much about the world and ourselves? Are we running out of unanswered questions? Is there too much beauty in the world? — too much Wisdom?

Have discoveries and developments in science and innovation reached a point of diminishing returns? I don’t think so — at least not of necessity. The moment Science and Innovation became the mistreated handmaidens of the monopolistic cartels which dominate today’s economy they were effectively neutered and drugged under the influence of money and petty privilege. Big capital is not fond of innovation nor does it tolerate discovery. Science and Innovation are anathema to the the doctrine of maximizing profits on capital already invested. While we enjoy the benefits of neoliberal “Free Markets” we should expect that no more than a trickle of discovery and innovation might ooze between the cracks.

Jeremy.

This is a great observation ! Thank you.

The ability of capital to buy academic researchers and use them as tools is really amazing. On the level, which Academician Lysenko did not even dreamed off.

I think this can be considered as a modern flavor of Lysenkoism.

Without going on a campus and talking with “salesmen” (re-capped professors now marketeers) at one of the many research centers located there it’s hard to gauge the full extent to which Big Capital owns Science and research. Grants for graduate students, money to support post docs all flows from the largess of Big Capital — and that largess comes with strings — well ropes and chains really. What I saw resided at a public university. What goes on at a private school is probably far worse.